The Life and Legacy of Rachel Held Evans

Speaker 1:

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour, a co-production of WNYC studios and the New Yorker.

David Remnick:

Welcome to the New Yorker radio hour. I'm David Remnick. The number of people leaving their jobs voluntarily, the quit rate, hit an all time high this year. That phenomenon is now known as the great resignation and it's shaking up industry after industry, from office jobs to restaurant work. The repercussions of the pandemic and how and where we work are going to play out for some time to come. Helping us understand all this is Cal Newport. Cal writes our column Office Space. He teaches computer science and he's also the author of the book, "A World Without Email." Lately, Cal Newport has been thinking about an idea that was all the rage not so very long ago. The four-hour work week. Your main work is as an academic, as a professor. How has this transformation, which is obviously inextricable from the pandemic so far, affected your own work as a teacher, as a writer, as a researcher?

Cal Newport:

Well, I think one of the obviously biggest short term transformations was this experiment we've been forced into over the last year and a half into what if we shut down offices? What if we make work remote? This has had an impact, of course, on academia, my university. Georgetown University was effectively shut down for most students and faculty for over a year. I felt this was a hard period. I'm happy now that I can actually be back and seeing my students. And it was an interesting experimentation in trying to figure out in higher education what's valuable and what's not. There was prognostications early pandemic that we would all realize that we don't need physical universities, because technically speaking on paper, you could deliver classes via Zoom and we were all going to see that. And that would be the demise of the university.

Cal Newport:

The opposite happened. Students hated it and there was a rush like how can we get back? And that's a theme that comes up a lot in this work, by the way, is that there's a lot of transformations that make sense on paper. The tech exists for this groundbreaking change to how we work, and then we try it. And there's a lot more complicating factors that rear their head.

David Remnick:

You recently wrote a piece for the New Yorker, revisiting something called the four-hour work week, not four-day work week, the four-hour work week. And then that was an idea that was popularized by Tim Ferris 14 years ago. What brought him to the idea of the four-hour work week? And what does it really mean?

Cal Newport:

He was in that early period, the first decade of the two thousands after the first.com boom followed by a bust, there was this big growth period where web 2.0 really picked up speed. Google picked up speed. Social media emerged. Silicon Valley became a heroic sector of the economy. And there was this whole culture of overwork that Silicon Valley was permeating out to the rest of the country. And Tim was an overworked executive... Entrepreneur, I should say, not executive. He worked at a company, became an entrepreneur, was overwork stressed out and basically ran a lot of radical experiments and realized, "I can run my company in about four-hours a week if my goal is just to live an interesting life and not to become a hectomillionaire. And so he wrote this book about it and he went to South by Southwest in 2007. It was the center of this Silicon Valley overwork culture and gave a talk where he told the people in the room, "You're working too hard. Give up on this goal of becoming rich with your stock IPOs. Live a more interesting life." And they were wrapped.

David Remnick:

And then wrote a bestselling book called "The Four-Hour Work Week," which provided him the economic cushion to propagate the idea of a four-hour work week. But it doesn't work for everybody. How can it possibly work for everybody? And what's wrong with working really hard if you have a goal, if you have some sense of ambition beyond the normal?

Cal Newport:

I asked him about that when I talked to him for the article and he's still highly connected to Silicon Valley. So he was quick to say, "There's nothing wrong with it." He says, "If you're trying to grow a startup, for example, you have to work 80 hour weeks. That's just part of the game. If you're a professional athlete," he mentioned, "there is certain standards of training. It's going to take up a lot of your time," and that's fine. What he thought he was doing was trying to introduce another option into the conversation that just trying to his model of trying to work, Intel retire make hard. He said, "That's good for some people," but there's these other options that he felt that technology was just making available. But what was interesting to me about that is that it was in some sense, a warning shot in that today, post pandemic or in stage a pandemic, lots of people are rediscovering the same ideas, "Oh, I can work remotely. I can have different arrangements with my work. I can also focus on other aspects of my life."

Cal Newport:

So he was actually quite prescient that some people might want to try something different. We weren't really ready for that message in 2007. However, today I think it's resonating a lot more.

David Remnick:

When we talk about a four-hour work week, are we being serious? That's it? Four hours? That sounds like not a hell of a lot.

Cal Newport:

The idea wasn't I think literally that everyone should work four-hours, but he would say in the book, and he's quick to say if you talk to him in person, that the bigger point is, question the assumptions about what work means, question about what you should actually be spending your time on. What's important. What's not. That actual hour will probably really differ depending on what you do. And Tim has said many times he works way more than four-hours now. But the point is, I guess, having that flexibility. I'll have to say, I like that idea. Four hours a week sounds about right to me. Maybe we should make that the standard.

David Remnick:

You recently wrote about how plans to go back into the office are creating a lot of tension all around for office workers, for managers alike. And you said that ambiguous plans are somehow good for executives but bad for employees. Why is that?

Cal Newport:

Yeah, when you come out and say, we have a tentative date, but I'm not going to tell you anything about what we're looking at and why we're looking at it. I'm not going to tell you here are our goals in reopening and these are the metrics we're looking at to see whether or not we've hit those goals. You have two issues. One is the transparency issue. I don't know, as an employee, what your goals are and whether I agree with them. And I think an employee should know, what is your standard? What are you looking for? Is it we should have no COVID spread in the office? Is it that we shouldn't have an undue burden on hospitals? Is it we shouldn't have undue burden on parents who have kids in school? That should be clear. And then the second issue is predictability.

Cal Newport:

If I don't know how these decisions are being made, you get this Groundhog day style setup, where then an executive can emerge, look around and say, "No, we're going to close for two more months." So it makes it very hard to predict what is actually going to happen. And my argument was that in part, this strategy of ambiguity is good for those making the decisions, because you can read the tea leaves and get a feel. Am I going to get backlash? Where are people, where are the culture and you can minimize basically your headache as an executive. That becomes the symptom that you're minimizing, but it's not necessarily good for all the people who have to live under it.

David Remnick:

Without a doubt. But isn't the problem, the pandemic itself? In other words, what we hope that a vaccine will do and now we're talking about the specific time that we're in, what we hope a vaccine will do is create a situation in which COVID is endemic. And that means people will have breakthrough cases. It's not as if people won't get sick just as they get sick from the flu and people do die from the flu. And there are cases where breakthrough cases can become more serious, although the vast, vast majority are not. So is there a cut and dried way to go back to work in your view?

Cal Newport:

No, I don't think there's any clear answer beyond clarity itself should be part of the answer. And this was really the view of Monica Gandhi from UCSF who I interviewed for this piece and she was saying clear off, rants from a public health policy perspective, have a lot of good value. That doesn't mean you're going to have perfect predictability. You're absolutely right. You could say, "This is what we're looking at." These two numbers put into this formula and you could be watching those numbers and say, "We're doing great." And then you get two weeks away from it. And something happens that we didn't predict. We've learned not to predict this pandemic, but clarity should be a part of the mix.

David Remnick:

You've said that work in some way is fundamentally broken. What do you mean?

Cal Newport:

When it comes to knowledge work in particular, we have a real tendency towards the improvisational and the haphazard. Unlike other sectors of the economy, I think when we looked at knowledge work, we put a lot on the worker themselves to figure out... How you organize yourself, how you say yes or no to assignments, how you plan your day, how you communicate and collaborate with people. We tend to place this on the individuals themselves. Management by objectives is the leading approach. We give you objectives and incentives. You figure out how to do the work. And I think this has caused a lot of problems. It's led to this haphazard approach to work where we're on email all day. We can't get away from Zoom. We're bothering people back and forth constantly. Can you do this? What about this?

David Remnick:

And when we say knowledge work, what does that mean?

Cal Newport:

So there's a million little definitions, but basically I'm using my brain, not my hand. Most of the work is happening in your brain and between your brain interacting with a computer. This digital era knowledge work, I think is the sub-sector where we're seeing the biggest changes to what work means. And so the way we are working in knowledge work, I think is far far from where we could be in terms of worker satisfaction and productivity, because we're not thinking about this at a systemic level of what's the best way to actually do this work. We make it too individualized.

David Remnick:

Well, there's a history to this. Isn't there Cal? There's a history of this notion of needing to be at work, the notion of the office as a factory. What's behind it?

Cal Newport:

Well, I mean, obviously there's an arbitrary aspect to the nine to five, we're in a building, we're there from nine to five. I mean, this came directly from negotiations about work hours from factory workers. And we have to remember that knowledge work emerged in an industrial context. And we used a factory as the main paradigm. It also gives us an element of surveillance that makes it easier to just say, "Be here and work. At least I know you're working. That saves me from the trouble of actually having to figure out what works means, how we structure work, how we track work, how we assign work." We can get away with not having to do that type of managerial effort if we instead just say, "Be in this building when I can see you. Answer my emails when I send them and we'll just rock and roll."

David Remnick:

So, we're talking as if this is a universal dilemma, and obviously there are lots and lots and lots of jobs in this country and beyond that, this is not relevant. And already roughly 13% of U.S. workers remain remote. That's it? 13%. So is the battle with the office as a factory already over to some extent?

Cal Newport:

I think the battle is going to be lost in the short term, but the war is going to be won. My prediction is that in the next year or so, we're going to see a pretty large scale retreat back to what I would call largely in-person work. I think there will be a more extensive granting of one, maybe two days a week that you're not at the office, but you still have to live near the office and come to it every week. I think that's going to happen because the friction of remote work will become too strong if we don't do significant other efforts to restructure how work happens. But I also think there's other economic dynamics that have already begun. That means in five or six years, we're going to see a much more widespread return to more aggressive remote policies. I think the pandemic planted the seeds for figuring out how to do that. Those plants, these metaphorical plants are going to grow so five or six years from now is going to be a vastly different workplace than it's going to be, let's say, next year,

David Remnick:

Is that related to what we've been seeing in terms of what's known now as the great resignation and huge number of people who have quit their jobs?

Cal Newport:

The real force, I think, that's at play here and I'm drawing this from an entrepreneur named Chris Herd, who I interviewed. He thinks startups that are starting right now, especially in the tech sector are figuring out how to make remote work actually work because they are starting as native remote companies. So they were forced to start in a period where they couldn't have an office building. So they're innovating. He thinks that innovation's going to then spread. Once they figure out how to do remote work properly, they will have an advantage, no long term leases, and they're going to have access to more talent for more geographic areas. That advantage means they'll dominate. And then the knowledge they learn will spread from these startups to bigger companies out of tech, to other sectors. I think that's actually the economic force that's going to cause a lot of changes. Companies are going to make more money once they can figure out how to do this. And that wisdom is being forged right now in the startup culture.

David Remnick:

Now you hope that the vision that's offered by Chris Herd, the entrepreneur in your piece, is correct. Show me exactly what that vision entails.

Cal Newport:

In that vision, there would be no central office for the company you work at. So there would be no constraint on where you live because there's no long term lease they hold on any building. In that vision, however, once every month to two months you would be in person with key people that you work with from that company. The location would differ depending on the purpose of the meeting. Are we brainstorming? Are we getting to know each other? Are we trying to push through an initiative? Are we doing a postmortem? And so you would have some connection, but Chris does make it clear that the office would not be the primary source of your social relationships. This would be a world in which you'd then turn to the local. You turn to other types of communities as your main source of social support. It would be a different relationship for a lot of adults with work.

David Remnick:

And who do you think will be for that and who will be against it?

Cal Newport:

Well, I think ultimately if that vision is correct, most companies will be for it because it's more profitable, which tends to be what the forces I bet on in the end, much more so than the forces of cultural change, to great resignation. Ultimately the forces that make massive changes at scales that dwarf any other sources when it comes to the commercial sector, tends to be, this is more profitable. And so if you do not have a long term lease your overhead per employee is lower. If you can access talent without geographic constraint, your return on talent investment is going to be much higher. So it's economic Darwinism at that point that if that works, that model is going to take over because those companies are going to be more profitable than their competitors.

David Remnick:

So it's simply the money saved on not having to buy or lease an office, a building?

Cal Newport:

Well, as a talent access. I think that's going to be huge. If I can access talent all around the world, not just in the Metro area where my office is built, that's going to be a huge advantage compared to competitors that don't have access to those same markets.

David Remnick:

And you don't think there'll be more discussion about offshoring talent?

Cal Newport:

When you go to a hypercompetitive globalized digital marketplace for talent there's a lot of, I think, downsides that come with that. As with most of these transformations they're rarely all positive, but if there's money to be made, they tend to be quite powerful.

David Remnick:

Cal Newport, thank you so much.

Cal Newport:

Well, thank you.

David Remnick:

You can find the writing of Cal Newport at newyorker.com. He writes our column called Office Space. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour with more to come.

David Remnick:

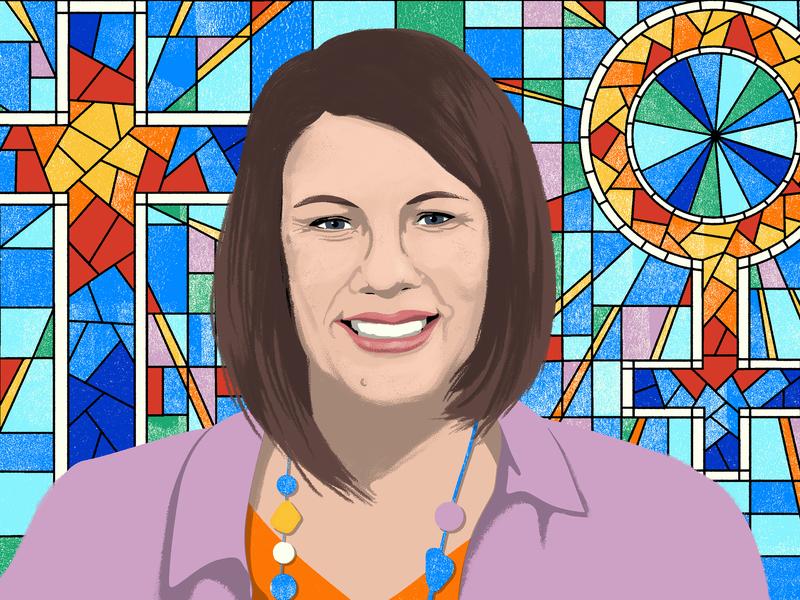

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. Rachel Held Evans grew up in the 1980s in an evangelical family, in a town and a community that was also solidly evangelical. But then she came to challenge many things about the worldview that she had inherited. Orthodoxies about the role of women, homosexuality, race, and much more. Held Evans went on to become an influential writer with a string of bestselling books that dealt with questions of faith. She was a linchpin in a movement among younger evangelicals away from conservative dogma. Here's Evans speaking on the podcast called Nomad in 2015.

Rachael Held Evans:

I kept feeling like I wasn't allowed to ask these questions. And yet those were the questions I was asking and those were the questions that a lot of my readers were asking. So it seemed worth addressing in books and on blogs, but it got me in a little bit of hot water with the evangelical establishment here in the U.S.

Speaker 5:

Progressive Christian author, Rachel Held Evans died this morning at the age of 37. She was known for her bestselling books and her progressive activism in the evangelical church...

David Remnick:

Evans died young after a sudden illness in 2019 and she left behind an unfinished manuscript. That book has now just come out. Its title is Wholehearted Faith, and it was completed by her co-author Jeff Chu. Eliza Griswold writes for us about religion and other subject and she's been reporting for us on Rachel Held Evans and her legacy. Eliza, you traveled recently to Dayton, Tennessee. What were you doing there?

Eliza Griswold:

So I went to visit the family of Rachel Held Evans and to get to know the people who were closest to her. And there was a dinner in her honor at the home of her husband, Dan, and he invited about 20 friends, including Rachel's parents and her sister, Amanda. And that day, they had driven me around downtown Dayton.

Mr. Held:

Wow. This is where Rachel and Amanda went to school. This is Dayton City School. It's-

Eliza Griswold:

Dayton's a pretty sleepy place. It's brick storefronts. Most of them seeming pretty empty. Kudzu kind of overgrowing the edges of streets.

Amanda Held:

Still here,

Mr. Held:

Right up here.

Eliza Griswold:

And in that tour, they really wanted to show me the courthouse, which plays a central role in Dayton's history.

Mr. Held:

This is the courthouse right here on your left. We'll get out here and you can see the two... If you want to. There's the two statues here. You can't miss this

Amanda Held:

Destination for anyone interested in history of evangelism in America. You don't want to miss this.

Eliza Griswold:

The courthouse is not just a Dayton landmark. It's also really important in Rachel Held Evan's story. It's the site of the Scopes trial, which was often called the monkey trial as well. And really was a turning point in modern biblical fundamentalism,.

Amanda Held:

The famous monkey trial that was almost a hundred years ago.

Eliza Griswold:

Yeah. So Dayton played a big role in Rachel Held Evan's upbringing. It was really the backdrop for how she grew up thinking about the need to defend evangelicalism and that involved a lot of absolute thinking that she came over time to reconsider and that was really a huge evolution for her and for many evangelicals. And she writes about it in this book which she very funnily calls Evolving In Monkey Town. And here's that argument at work. "If we can adjust to Galileo's universe," she writes, "we can adjust to Darwin's biology, even the part about the monkeys. If there's one thing I know for sure it's that faith can survive just about anything so long as it's able to evolve." This is not old history to her. This was really a battle over what it means to follow Jesus today.

Mr. Held:

These statues are fairly recent. The Darrow one came much later than the Bryan statue. And then it was several years later that... And I don't know who commissioned the other statue said, "Well, if you're going to have a Bryan statue, you got to have a Clarence Darrow statue." There was a little resistance to that, but not much.

Amanda Held:

Bryan has a light that shines on him all night long, but Darrow doesn't get a light at night. They didn't put a light up for Darrow.

Eliza Griswold:

That's so great.

Amanda Held:

So not a whole lot's changed in 100 years.

Eliza Griswold:

Amanda, what was the idea growing up of the Scopes trial? Was it like William Jennings Bryan was the hero.

Amanda:

Yep. And defending against the carpet bagging, liberal northerners. Who didn't believe in God and didn't respect the Bible. I don't even know that that was explicitly taught.

Amanda Held:

You think it was?

Eliza Griswold:

It was just kind of the tone, you know what I mean? It was just the general understanding and no one really knew that the town folk had been the butt of the joke, in terms of the media coverage and things like that. We didn't really talk about that. That's something I learned later.

David Remnick:

Eliza, I think we can hear from even that the beginning of the culture war somehow.

Eliza Griswold:

So for evangelical Christians, this idea of defending the faith comes very much out of the Scopes trial and not just defending the faith against the liberal secular north, but also defending the faith among fellow evangelicals who would choose to recede from society. So this group is very much about engagement and Peter, Rachel Held Evans' father, who we heard in the car is a professor of Bible studies at Bryan College, which is known for William Jennings Bryan. And he actually teaches a class on angelology, which is the study of angels and demons and spiritual warfare. And so they moved here so he could be a professor at Bryan when Rachel was in eighth grade and she was not just like an enthusiastic young evangelical. She was a fiercely competitive evangelizer and she cornered kids on the school bus and tried to convince them at 6:45 in the morning to give their lives to Jesus.

David Remnick:

And then along comes a turn in her life, a real turn. And when you're raised and your father is a professor of angelology and you've inhaled this powerful belief system, what made her leap out of it?

Eliza Griswold:

What happened for her, she was in college when the U.S. invaded Afghanistan and she was watching on a replay loop, a Taliban execution of a woman who was accused of committing adultery. And it was with watching that, that she had this spiritual crisis because she was like, "How could that woman be going to hell? By nature of geography that, where she lives, she hasn't heard of Jesus," and that for her was the beginning of a larger unraveling of these received ideas about absolute faith, about who saved and is damned.

David Remnick:

Yeah. And I remember that very clearly. The coverage of that was live on television and showing her being executed and that just started questions about, wait, what? What happened to her? Does that mean she'll spend an eternity in hell and starting questioning, "Is that fair?" Questions about the justice of God and judgment and how can we believe what we believe? And I could see she was worked up over it.

Amanda:

I was thinking that as you were talking that I think part of it for Rachel too, was that we grew up in this... It was the height of the evangelical apologetics movement, where we went to all these conferences and about how to defend your faith. How to have an answer for what you believe. And so just the subculture and church and Bryan... And so I think that's why it was particularly unsettling to have questions is because we were taught to have answers. We were to taught to be confident, to have a reason, to have an answer, to give an apologetic for why we believed what we did. And so that's why I think Rachel didn't quite know what to do with her questions, because even though our home was a safe place for that, the subculture at large wasn't.

David Remnick:

What did we Rachel do with that? Where did she take those questions?

Eliza Griswold:

So after she graduated, she married her college sweetheart, Dan Evans, and she went to work at local newspapers, writing style features like one about hermit crabs, but she was really still struggling with aspects of her faith and her husband, Dan, encouraged her to start a blog.

Dan Evans:

Blogs weren't new at that point. This is 2007, but still a fairly new idea.

Eliza Griswold:

And she wrote super friendly, soft posts, like raising kids in faith. And she wrote pretty hard edge controversial ones too. Like a takedown of Mark Driscoll, who was the pastor of the hugely popular Mars Hill Church. And he and his church have now both totally collapsed due to allegations of abuse, but really the blog allowed her a whole new audience and a whole new reach.

Dan Evans:

I just remember we first started the blog, we broke double digits. We got up to like 10 people who had subscribed. And then when it got a little higher than that, closer to 20, we started thinking, counting up on our fingers like, "Okay, there's got to be people reading that we don't actually know. That was a fun experience. I remember watching it grow. Yeah. We was like, "Oh man, can we break a hundred?"

Eliza Griswold:

And through that blog, other like-minded people who were afraid to ask the same questions, found her and began to read her work. Long story short, her blog grew and she attracted this massive community of readers and started publishing books. Her first Evolving in Monkey Town, her second, A Year Of Biblical Womanhood, which was a pretty hilarious send up of what biblical literalism looked like. If you lived according to being a good wife, as this culture had called for like she slept in a tent outside, she stood on a roof to do these biblical injunctions. And by doing so, really pointed out the absurdity of them. Here's Dan in the car showing me where are some of those stunts took place.

Dan Evans:

In Proverbs there's a passage that talks about a woman praising her husband at the city gates. And so Rachel held out a sign that said, "Dan is awesome," and stood right there in front of the entrance to Dayton because it's also good to have some strong marketing.

David Remnick:

What was the reception of her work in the greater evangelical world? Were people reading her?

Eliza Griswold:

People were pretty hostile about her work while she was alive within conservative circles. And her dad really bore the brunt of that, because he's still very much at Bryan within that world, but the reception to her work outside of it or within those who were questioning it, I mean, we're talking millions of people who followed her and revered her as really the patron Saint of this emerging movement.

Dan Evans:

She was making things better for a lot of people and the complaints against her didn't have anything to do with her ruining people's lives. The complaints against her were always too inclusive or not using the right terminology or not calling God he all the time or accepting people were just gay, things like that. The people who had the complaint didn't really have a ground to say, "You are hurting me," and the people that she was helping had the ground to say, "You're helping me. Like I didn't kill myself because of your work." So yeah, I was definitely invested in that.

Eliza Griswold:

I think Rachel really founded a movement, right? It think that she did. And I think that partly because as I watched the fissures of evangelicalism, right, I meet so many people who are like, "Oh, I have the courage to do this because I watched her blog," right. She gave them permission to speak out what they really... Because they saw there was an audience.

Dan Evans:

My ego wants to agree wholeheartedly.

Eliza Griswold:

David, it's important to understand about Rachel Held Evans, that she was a pretty rigorous self-taught scholar. And one of the things that she did was reground the Bible in Hebrew tradition in which it actually belongs. And by doing so, reclaim the authority and reclaim the roominess and reclaim the intellectual underpinnings of a faith that allowed people to find space for themselves in it again. Dan showed me this important text on the wall of their house, where she wrote books. This is like a picture of a crown in Hebrew or-

Dan Evans:

So this is a scroll.

Eliza Griswold:

Okay.

Dan Evans:

And this was done by a Rabbi in Israel because this is Eshet Chayil, Proverbs 31, woman of valor. So you have Proverbs 31 in the shape of a crown and Proverbs 31 was at one point a sticking point for Rachel because it's about this valorous woman and evangelicalism. It was always held as an ideal that you're supposed to ascend to. But in Jewish culture, it was a song of appreciation for the things that you have already accomplished as a woman.

Eliza Griswold:

I see.

Dan Evans:

And it's a completely different perspective and Eshet Chayil Rachel's bringing of that understanding to evangelical women had such an impact. People got tattoos of it on their arms. It was one of the things that "Year of Biblical Womanhood" brought to evangelicalism that Rachel facilitated.

Eliza Griswold:

It's like a freedom from some of that misogyny and complementarian ideas.

Dan Evans:

You don't have to ignore the Bible. You can use the Bible and say look, "Recent Christianity is not the only way this has ever been interpreted." In fact, there're entire generations of people that precede us that have a better understanding of their own scriptures that we can listen to. And guess what? It doesn't throw women under the bus. In fact, it elevates them. And that was the entire point.

David Remnick:

That's Dan Evans who was married to the late writer, Rachel Held Evans. Our story about Evans's life and work continues in a moment.

David Remnick:

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. Let's continue now with this story from Eliza Griswold, about the late Rachel Held Evans, a bestselling Christian writer. Evans in her books, in her blog outlined a progressive version of evangelical faith very different from what she'd grown up in. The new book is called "Wholehearted Faith" and it was co-authored by Jeff Chu.

Jeff Chu:

Could I get a pound of pork belly? Let's do both pieces. Yeah. I want to make sure they have enough food.

Eliza Griswold:

I went to Tennessee with Jeff Chu and Jeff was a dear friend of Rachel Hale Evans and he also finished her book for her after she died. And in addition to being a writer, he's also quite an accomplished Chinese cook.

Jeff Chu:

Okay. Could I do two pounds of Cod please?

Eliza Griswold:

And so for this night he had offered to cook dinner for Rachel's family and friends in order to celebrate the book. He hadn't accounted for the fact that Dan Evans might invite 20 people. So it was a little bit of a Hail Mary going to this Whole Foods to get everything that he thought he needed.

Cashier:

Fun going on today?

Jeff Chu:

We're going to make a big dinner.

Cashier:

That'll be good. What are you making?

Jeff Chu:

Chinese food.

Cashier:

Right on.

Eliza Griswold:

It was really Dan Evans who chose Jeff Chu to finish Rachel's book. And Jeff quite honestly was pretty reluctant about doing it.

Jeff Chu:

I wanted to say no for multiple reasons, but probably the biggest one was that saying yes would mean I would have to admit that she's not here anymore. And I was just afraid that I wouldn't live up to her standards of writing, which I knew were extraordinarily high.

Eliza Griswold:

But Jeff did finish the book over really a painful period of pandemic, sifting through not only the chapter she'd left behind because she left behind 11,762 words, but also talks she'd given, blog posts she'd never posted, family stories, anything, old Christmas lists, anything that was on her computer. He used the source material as a journalist to try to piece together not only a life, but the evolving theology of his dear, dear friend. And in a way there was a parallel as he made between trying to just work with what you've got and then making this huge gift of a Chinese feast for her family and friends with basically whatever he could figure out on the spur of the moment.

Jeff Chu:

So, I'll steer it off and then put it in the stew.

Eliza Griswold:

Jeff spent all day cooking. The kitchen grew warm and [inaudible 00:34:11] with garlic and scallions and people began to arrive. First of all, her family and when her sister, Amanda just went right to work, rolled up her sleeves, washed her hands and started rolling Won-Tons and Spring Rolls at Jeff's very specific instruction.

Jeff Chu:

Can you fold a square piece of paper into a triangle?

Amanda:

Sometimes, usually. If the cooking doesn't involve like pork fat, then I don't know how to do it. All I know is Appalachian Southern cooking, but that's all I know.

Jeff Chu:

So actually it sounds like you were having a good time. A real feast. Who was at the table?

Eliza Griswold:

It was like a Southern episode of Friends. It was her high school and college friends gathered around telling stories that many of them hadn't heard before. I mean she died in 2019, but for many of them, this was the first time they come together to really celebrate her and to do what she did the best, which was poke gentle fun at her. Like her playing the piccolo and closing a flute in the door of her high school band bus. And she was this enthusiastic, almost rabid evangelist who would seek out anybody she could find to try to bring them to Jesus. There weren't many atheists or even Presbyterians at the Dayton High School. But Rachel did her best to find the tiny handful that she could.

Amanda:

I think one of them rode the bus with us and she was like, "This is amazing. Like, this is why God is allowing me to walk through this hardship of having to ride the bus," because mom and dad wouldn't buy her a car. And so she was like, she had to ride the bus, but fortunately she sat down next to an atheist and-

Eliza Griswold:

Rachel's friend, Kathleen was there too and Kathleen was Rachel's freshman year roommate at Bryan.

Kathleen:

I remember for me coming to Bryan was freedom. And I grew up in legalism and abuse and definitely thought that I was bad because I was a woman. So I shouldn't trust my emotions or my feelings and even my mind. This is what I was taught.

Eliza Griswold:

Kathleen grew up in a fundamentalist church in Pennsylvania and she and Rachel would lie in bed and they would talk about womanhood basically and what it meant to be a devout woman. And in particular, they'd talk about Proverbs 31, which in white evangelical culture is one of the principle texts by which women are defined as staying home and being good mothers and being good wives and submissive to their husbands.

Kathleen:

So the Proverbs 31 woman gets up early. Oh man, I've been in trouble my whole life. I'm not, that's not me. Sometimes I tell my husband, I'm the bad Proverbs lady. There's like the one that you're warned against. I'm like, "I think that's me." But anyways, so I think it was just perceived as like the formula for how you're supposed to be, which was translated into being a woman who your life is, kids, keeping the home and getting up early and cooking and making things from scratch and just like a woman who can do it all. So I remember with girls talking about that and wanting to be that and Rachel pushing back against that. Like I'm not sure that we're using this passage in the right way or as simple as, "I don't think we really have to do all that to be godly." I loved that. I was like, "Oh, all right."

Eliza Griswold:

So Kathleen told me that she had left her church when her pastor came out in support of Trump's policy of child separation at the border and she was pretty appalled and she was also scared. So she gave Rachel a call and Rachel told her to come right over.

Kathleen:

I just couldn't be alone. I was just so scared and I went to her house and she gave my kid goldfish, sat him on the couch with like Paw Patrol, gave me some of Dan's birthday cake. And then I remember asking her, "Am I going to hell?" And I'm just like crying and her response was just like so comforting. It was just like, "Of course not." And she just held me and I just sobbed, just shook and sobbed and she let me talk with her for the rest of the day.

Eliza Griswold:

Kathleen, one question I asked these guys earlier is how Rachel's journey of faith affected your own?

Kathleen:

Hmm. I would say, I still have faith because of Rachel because I almost lost it.

Eliza Griswold:

David, this is something we probably should emphasize that there's this common misperception that either you are a conservative evangelical Christian or you leave that and you become agnostic or atheist. But the truth is that Rachel Held Evans is part of this turn within Christianity, away from conservative Republican culture of a reclaiming of faith outside of politics.

David Remnick:

You mentioned that her father, Peter Held, bore a lot of criticism about Rachel while she was alive, especially in conservative evangelical circles. What's been the response more recently?

Eliza Griswold:

The response is overwhelmingly positive. And I know that among the conservatives I talked to pretty regularly there's regret at not hearing her wisdom earlier and hearing some of the misogyny and the racism that she was calling out has really now fallen from grace. But at the time she was alive, it was still pretty risky and pretty brave of her to name some of these things so publicly.

David Remnick:

Now, you're talking about people who are either former evangelicals or progressive evangelicals. What is the scale of that community? Give me a sense of it relative to the, I would assume, much larger community of traditionalists conservative, right wing evangelicals.

Eliza Griswold:

So the scale is pretty overwhelming. I mean, if you look at it numbers wise from 2006 to 2020, you can see the number of white evangelicals in America dropping from 23% of the adult population. So nearly a quarter of Americans identified with this movement. Now that number has fallen to 14%. So very roughly that's something like 15 million people. And I think where we get it wrong, sometimes looking in from the outside is we see this as a growing secularization, but that's not necessarily what it's about. And Dan and I talked about this and we were on his porch in a torrential rainstorm.

Dan Evans:

For a long time people wanted to shift evangelism, but that's not really what's happening. I think what's happening is the evangelism is shrinking as less fewer and fewer people describe themselves as evangelical. So I think evangelism's issue with people being gay, for whatever reason, is probably still a part of that identity. I just think the shift is people moving out of evangelicalism. What I will say is the people leaving that community are still looking forward to a spiritual community. There's a lot of social inertia to still be able to claim some part of Christianity and spirituality and not ostracize the group that raised you. It's just such a real thing to not want to lose that group. And it is a search at some level for meaning.

Eliza Griswold:

So Rachel and Dan actually left evangelicalism and they went searching for a new church. They started their own, which didn't take very well. And so Rachel ended up going on to join an Episcopal church. Why the Episcopal church? Was it this particular church? Was it Episcopalianism in general? Was it its welcoming affirming stance for gay people?

Dan Evans:

That was certainly a part of it. A larger part was the liturgy. Having all that history, that was meaningful to her, because words were always meaningful to her. And the fact that the climax of the service wasn't the pastor. The climax of the service was communion. And that shifts the perspective of what's most important in a church. Is it really a certain person in that building or is it the community?

David Remnick:

Eliza, who's going to carry on her legacy? She was a major figure in this movement.

Eliza Griswold:

In terms of the nuts and bolts of Rachel's legacy, Dan feels the responsibility at least for now, but he's really careful about speaking for Rachel. He always refers to what she herself has written and he's struggling to build his own life. He has two tiny kids to raise. He has a new fiancée and he's really between two lives. It's important to him as his kids come to him though and keep asking questions about her death, that he explains what that loss means in terms that are incredibly literal and don't branch into any ideology or supposition or any talk about heaven. Dan explained this to me when we were outside on his back deck in terms that were wrenching and stark and really honest.

Dan Evans:

So this is our back deck and that-

Eliza Griswold:

Beautiful.

Dan Evans:

... is where I had the hardest conversation of my life. And that was when I sat my three year old down and had to explain to him that his mom died. I said, "Mommy died." And he said, "Why mommy died?" Because he's not even sure what that means. Like is a died a thing that she got is... And so I said, "Well died is when your body doesn't work anymore and you can't move your arms, can't move your legs." I said, "There's no pain, mommy doesn't hurt. And she's not sad."

Eliza Griswold:

Does he ask about things about heaven and does he ask where she went and do you get into some of the...? People must talk to him about that stuff or-

Dan Evans:

So what I, yeah, because we've had multiple nannies over and everybody has different belief systems. And what I have suggested is we talk about the things that we all know to be true. And as he grows and develops a sense of spirituality, I think he's going to probably have his own examining to do, but for me, it's worked really well to frame it as, "Guess what? Grownups don't know." We don't know what consciousness even is. So best thing just to go ahead and let the kids know. We don't have this figured out.

Eliza Griswold:

That's great. Wholehearted Faith in part is about embracing that doubt because for Rachel growing up, the idea of doubt was sinful. Faith had to be absolute, but one of the tragedies on the page is that these questions she's asking of doubt, of the idea of worthiness, of being beloved by God are not finished questions and that theological journey, which she talks about evolving, just stops.

Dan Evans:

Yeah.

Eliza Griswold:

Right? And I'm like-

Dan Evans:

Forever those will be the last 11,000 words that she ever wrote.

Eliza Griswold:

Right.

Dan Evans:

For the book.

Eliza Griswold:

Right. And because her evolution was such a beacon for other people, how are they going to go on?

Dan Evans:

Rachel did a really good job of ensuring that she was walking on the same path with people and she wasn't really leading them along. And this is why I think people resonate so much with her work is she was giving words that people couldn't say themselves. It was because Rachel's unique way of putting those words together, gave voice to the thing that already existed in all the people. And so those people are going to still have those thoughts and there will be other people who are able to put into words some of their feelings, but it's not going to stop for them just because Rachel died. There's going to be one less traveler. There's one less person to translate for them. But there's more people born every day.

David Remnick:

Eliza, this new book is coming out without its main author alive to talk about it. And we both know how important book promotion can be. Do you think that will make any difference in the reception of the book?

Eliza Griswold:

She had a children's book come out that was also posthumous and it was the number one New York Times Children's Bestseller. And I think that this book, because of the hunger for her message, I don't think it's going to matter whether she's there to speak it aloud or not. It's on the page.

David Remnick:

Eliza Griswold is a staff writer for the New Yorker and her story, the Afterlife of Rachel Held Evans is at newyorker.com. You can hear more from Eliza on the state of Christianity and more on the podcast of the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. Thanks for joining us and see you next time.

Speaker 1:

The New Yorker Radio Hour is a co-production of WNYC studios and the New Yorker. Our theme music was composed and performed by Merrill Garbus of Tune-Yards with additional music by Alexis Cuadrado. This episode was produced by Alex Barron, Emily Botein, Ave Carrillo, Rhiannon Corby, KalaLea, David Krasnow, Ngofeen Mputubwele, and Louis Mitchell, Michele Moses, and Steven Valentino.

Speaker 17:

With additional help from Priscilla Alabi and thanks this week to Kim Green for production on our story about Rachel Held Evans.

Speaker 1:

The New Yorker Radio Hour is supported in part by the Charina Endowment Fund.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.