Ryan Coogler on “Sinners”

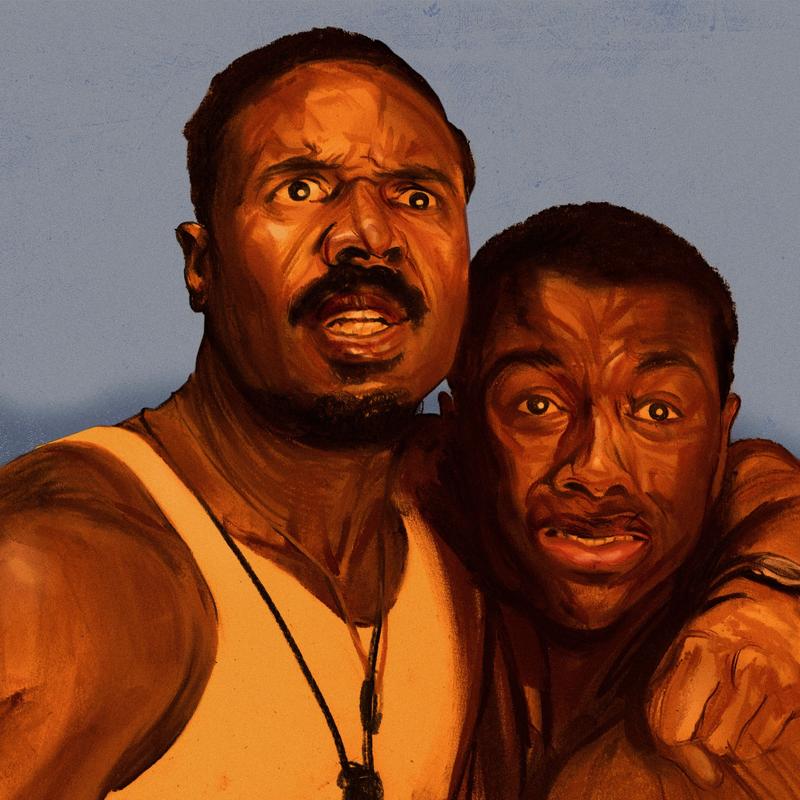

David Remnick: Ryan Coogler began his career in film as a realist. His indie debut is called Fruitvale Station. It's a tragedy about a police killing in the Bay Area train station, and it scrupulously followed the last day of the victim's life leading up to the shooting. Coogler moved from there to the drama of Creed, about a young boxer, a film that was in the line of Rocky. Then he went on to make the super commercial widescreen fantasy, a Marvel hit called Black Panther, of course. In his new movie, which is called Sinners, Ryan Coogler is still dealing with themes of race and history and faith, but this time, he's packed it with vampires.

Cornbread: What y'all doing? Just step aside and let me on in now.

Annie: Why you need him to do that? You big and strong enough to push past us?

Cornbread: Well, that wouldn't be too polite now, would it, Ms Annie? I don't know why I'm talking to you anyway. Smoke.

Annie: Don't talk to him. You talking to me right now. Why you can't just walk your big ass up in here without an invite, huh? Go ahead, admit to it.

Cornbread: Admit to what?

Annie: That you dead.

Cornbread: [laughs]

Jelani Cobb: I've been interested in talking to Ryan Coogler for years because I thought he had a really kind of nuanced and subtle way of seeing the world and certainly of seeing people.

David Remnick: Here's staff writer Jelani Cobb.

Jelani Cobb: On the other side of Black Panther, which was this gigantic movie and made him the largest-grossing Black filmmaker of all time, and I believe the youngest filmmaker to ever gross a billion dollars for a film, there was this big picture of him, and I didn't know if all the details of who he actually was as an artist had been filled in. I thought it would be interesting to write about him and fill out the silhouette a little bit.

David Remnick: Jelani Cobb sat down in our studio the other day with Ryan Coogler.

Ryan Coogler: It's always good to see you, bro.

Jelani Cobb: Good to see you as well. I want to talk a little bit about how you approach a film that is simultaneously about religion, it's about music, it's about the relationship between fathers and sons. It's set in the Jim Crow South in the 1930s in Mississippi, so there's an element of race and vampires.

[laughter]

Ryan Coogler: Yes.

Jelani Cobb: Of those themes, how did the vampire element become part of that story?

Ryan Coogler: I had the desire to make something that was uniquely personal. What that means is I wanted to make the thing that only I could make. Look, all my films have been personal. I've been fortunate enough to build them as uniquely as a filmmaker could. They all did start with something that existed outside of myself. With Fruitvale, we were adapting the story about a young man's life, a young man who was murdered by a law enforcement officer.

Where I'm from in the Bay Area, there was a great awareness about Oscar Grant, and a lot of people knew him personally. Even if you didn't know him, you knew who he was. You saw what happened. You saw the story play out. You saw the awful video footage. With Creed, it was a pre-existing franchise that I had an idea for an entry into it. I never imagined that it would spawn sequels to that and things. I was looking at it as a singular thing at the time. It was very personal story inspired by my father's love of those Rocky movies and that love being handed down to me. It was not something that came from me initially in its entirety.

With the Panther films, I was hired onto that movie. That was something that Marvel was making. They were looking for a director. Fortunately enough, they called me and were interested in what I was trying to do with it. This time, I had an opportunity that is very-- it's a rare opportunity. I knew it was because of the financial success that these previous films have had, that I could mortgage or leverage that success into doing something that's uniquely mine, that would not exist in the world if it wasn't for me and what I like, and what I'm into.

The film is really just based on my interests, you know what I'm saying? I love horror movies and I absolutely love music. Music I use, it's the art form I use in so many different ways. I use it if I want to communicate something to somebody that I love. I use it if I want to calm my mind, if I want to influence a room of strangers. As a kid, I used to use it to travel, you know what I'm saying? I hadn't been anywhere, but I would listen to Mobb Deep and Nas and say, "Oh, man, this is what New York must feel like. I listen to DMX and say, "Oh, man, this is what the East Coast must feel like."

Jelani Cobb: Can I say, I'm interested in this idea of this kind of film representing a culmination that you've been working, kind of really well-received independent film, Fruitvale, and then three franchise films that have been well-received artistically and commercially. Then being able to spread your wings and do this project, which also made me think about another theme that's so prominent, which is the theme of, I would say Christianity, but it's actually more broadly spirituality since there are lots of different kinds of spiritual practices and beliefs that people foreground in the film.

I hadn't seen that in your previous work, and I wondered how that came to you, how it connects to your own beliefs, your own thinking about spirituality and religion, and how it made its way into this film.

Ryan Coogler: I'll tell you this. I actually thought about this in all four of my movies before this. There's a moment in the movie where a character experiences the afterlife. For me, those are the strongest moments that I remember either finding them in post-production or them always being like an intentional design when I was writing no more. It happens in this movie, too, in a lot of different ways. It is something like retroactively, I realized recently, and it's something that I'm always dealing with. I was raised Christian, Baptist, and in the Black tradition, and product of the second wave of the Great Migration.

Jelani Cobb: Your family came from Texas, correct?

Ryan Coogler: My mother's family came from Texas through her matrilineal side, but her patrilineal side was from Mississippi.

Jelani Cobb: Oh, okay.

Ryan Coogler: Her mother was from Port Arthur, Texas, and she married a Mississippi man who was in Oakland. He passed away before I met him. I remember, bro, I remember being young and I was in Catholic school, and it was a Black Catholic school. We had a lot of those coming up. I had religion in school, which was like a different type of vibe. You go to mass and sit down, stand up, sit down, stand up, singing these slow songs. I felt very disassociated with it. I felt like being in class, but worse, to be honest. Then I would go to church on Sundays where my mom's singing in the choir, belting out notes, and my pastor grabbing people, slamming them.

[laughter]

Jelani Cobb: It's like the Baptist thread and the Catholic thread. These two things are not the same.

Ryan Coogler: Not the same. I recognize some of the songs that were sung differently, and I remember gaining, essentially, consciousness enough to understand that, "Oh, man, my parents' parents are dead, some of them." I remember having conversations with my dad about his parents who had both died before I was born. My mom's dad had died before I was born.

I remember coming up at that age, three, four, five, and asking them about their parents and hearing about, "Oh, man, their parents are dead. Are y'all going to die?" and being up late at night when they're telling me about heaven and how it goes on forever and trying to understand this concept of an eternity, or to understand this concept of my mom saying, "Yes, but my father is still with me, and I know he's proud of me. I know he's proud of you."

Like in this concept of my relationship with the afterlife, with my own mortality, and how that looks through a Catholic lens, or a Christian lens, or a Baptist lens. It was something that I've been reckoning with forever. I'm looking back on my work and I'm like, "Oh, yes, I'm still reckoning with that." For me, this film is about a lot of things, man, but it's also about the act of coping.

Jelani Cobb: The coping part of the film, I think, comes in, even on some level, to the kinds of vampire element of it, too.-

Ryan Coogler: Absolutely.

Jelani Cobb: -which is one of the things I thought was really interesting because I've seen my share of vampire films. I don't think I'd ever seen the vampire question presented in a spiritual frame in the way that these characters do in some ways.

Ryan Coogler: That was very important to me, man. If there was anything that was akin to the techniques that I learned from franchise filmmaking, it was how do I deal with the vampire? Because the vampire is not an idea that I own. None of these ideas in the film are ideas that I own. Like the tortured blues musician, the gangster identical twins, the conjured woman, the racially ambiguous person.

Jelani Cobb: These archetypes.

Ryan Coogler: Yes, these are archetypes. I was very, very serious about going there, dealing with the archetype with this movie and the international shared experience and knowledge of what a vampire is and what that means and the expectations. For me, it was like, "All right, how do I make this concept my own? How is this a vampire the way that I like to tell stories, one that's unique to me?" The movie deals with the Faustian deal. I was very obsessed with the ancient. The most notorious Delta blues story is the story of the musician who goes to the crossroads. Oftentimes it's thought of being in Clarksdale, Mississippi-

Jelani Cobb: That's right.

Ryan Coogler: -and making a deal with a nefarious, metaphysical character.

Jelani Cobb: Right. The Robert Johnson narrative.

Ryan Coogler: The Robert Johnson narrative. Now, I did some research, most extensively with Amiri Baraka's work and also--

Jelani Cobb: Blues people, the critic and playwright.

Ryan Coogler: Exactly, and Deep Blues by Robert Palmer. They talk about how sometimes it's the devil, sometimes it's Papa Legba.

Jelani Cobb: Papa Legba. Right.

Ryan Coogler: It's these ancient--

Jelani Cobb: It's a reference to the deity Papa Legba, who is common in kinds of African forms of spirituality that came with enslaved Black people into the South.

Ryan Coogler: Yes, sir.

Jelani Cobb: Sometimes people have that idea that Johnson is at the crossroads not talking to the devil. He's talking to this deity figure, Papa Legba.

Ryan Coogler: It's African spiritualism.

Jelani Cobb: Exactly.

Ryan Coogler: That idea of the Faustian bargain. Not just to be a good guitar player, but to have a better life. Like how much of yourself do you have to give up to do X, Y? We all make them. Whether it's on a movie deal or a publishing job or a teaching gig, it's always like, "Man, what of myself am I going to give up to have whatever this thing offers for me, maybe in the distance, momentarily, for my family?" It was the bargain that my parents had to make to send me to parochial school.

When I realized that that was the most notorious story at his music from this place, I said, "Oh, the movie has to be about that." What if vampirism is a deal that they selling? What is the upside to it? What's the cost?

Jelani Cobb: Yes, that's amazing. One of the things when I was talking with Zinzi, your wife, and your frequent collaborator and co-producer on this film, and she compared this with Black Panther, with the two Black Panther films, you talked openly about, before you made Black Panther, going to Africa to actually get a kind of understanding of Black Americans relationship with the African continent.

Ryan Coogler: Yes.

Jelani Cobb: Zinzi pointed out that it was like you were grappling with the questions of distant African ancestry in that film and here grappling with more immediate questions of ancestry in this country, in Mississippi, where the film is set, even though it's shot in Louisiana, but it's set in Mississippi, and that this is the same ancestral exploration happening here.

Ryan Coogler: Absolutely, man. Man, it was such a blessing to be able to make this movie. It's very sharp of Zinzi to make that assessment. She's the sharpest person I know, man. No, she's absolutely right. What's funny is I went to Mississippi, and that is the most African place I've ever been outside of being in the continent.

Jelani Cobb: What do you mean by that?

Ryan Coogler: Number one, the feeling that I got. It was a feeling that I got when I first touched down on the continent, and I get it every time I go back. It's difficult to explain. I tried to think about it in a tactile manner and tried to translate that into the film. I remember I got out of the car in the Mississippi Delta and I was like, "Oh, wow, I feel like I'm back." For me, it was deeply profound, man. It was like, oh, through the process of making Black Panther, I realized, all right, African Americans are extremely African. We may be more African than we know, and realizing that the 400-year distance from the continent, there was no way it was ever going to change. Thousands of years of culture.

With this, it was like, "Oh, we affected this place. We brought Africa here. That was what I realized was we had the power of transformation, man, over landscape, over feeling. It's known that the music came from that place, like the most influential form of blues music, the Delta blues. It came from that spot. Realizing that, "Oh, we didn't just bring Africa to this patch of land here, which is the American South." We didn't just do that.

Also, these people who lived in these awful conditions produced an art form that changed the world and continues to change. It redefined everything. It was before and it was after. That, to me, was like, "Oh, this movie's big. This movie's bigger than I thought. I thought I was making something small. Now I'm making something massive." I realized in that moment, if I do this right, there's an argument that there shouldn't be a bigger movie. From there, it was like, "Okay, IMAX."

Jelani Cobb: That's actually what I wanted to talk about because literally, the size of the film. The last time I saw you, we were in the IMAX offices and they were showing the reels of the film. First off, I had no idea the reels were that big, like 500, 600 pounds to show this film. You were talking about how significant it was for this film in particular to be shown in those dimensions. Can you talk a little bit about why you felt like that was important?

Ryan Coogler: Yes, man. I'm getting into relationships then. The first two films I remember watching were Boyz n the Hood and Malcolm X. I'm fortunate enough to have gotten to know John Singleton before he passed away. Rest in peace, John. He became a mentor of mine. We went to the same alma mater.

Jelani Cobb: USC Film School.

Ryan Coogler: USC Film School, School of Cinematic Arts. I'm fortunate enough to have gotten to know Spike Lee, and he's become a mentor for me. I know from John's mouth that he made Boyz n the Hood because he went to go do the right thing and got so inspired and also so jealous-

Jelani Cobb: Of Spike Lee's film.

Ryan Coogler: -of the movie. He said, "Man, I want something like this for Los Angeles."

Jelani Cobb: Wow.

Ryan Coogler: He goes home and writes Boyz. I watched that as a child. Obviously, both these guys are cinephiles. It's hard talking about John in past tense. They both have an encyclopedic knowledge of the craft. Hearing Spike talk about Malcolm X and going door to door with Black celebrities to raise money for--

Jelani Cobb: What does that mean to you to have to do that?

Ryan Coogler: I've never had to. I'm getting emotional because it's hitting me now because I'm talking about the ease of which I can make a vampire movie this expensive. Malcolm X is one of the most important Americans to ever live. Not even for our culture, but for pop culture. You get no X-Men without Malcolm X. You get no X Clan. The fact that he had to go door to door to the Black community to get enough money to go make the story of Malcolm X in a way that it deserved, that just hit me like a ton of bricks, coupled with the fact that John ain't here no more.

For me, I saw both those movies, bro, and the epic scope of that. When I talked to Spike, he knew what an epic film should look like, what it should feel like. He knew that Malcolm's story was deserving of that. I realized, "Oh, man, you can make the argument that Delta blues music is the most important American contribution to global popular culture." You can make that argument. These people were important, bro. They weren't scientists, they weren't physicists. These were just human beings trying to make it under a back-breaking form of American apartheid, breaking everybody's backs.

That act of affirmation of that humanity, that deserves epic treatment, too. It deserves the most epic treatment. I'm sitting there with Spike. Spike's mentor now. I'm making a movie about blues vampires. I ain't have to knock on Oprah's door. I ain't have to ask Michael Jordan for money. I have to do that. I said, "Man, I got to go for it." Because this music, it changed the world, and these people had nothing.

Jelani Cobb: Listen, this has been an incredibly insightful tour of how you think about film and what filmmaking represents to you. I want to say thank you for taking the time to talk with us today. Good luck with the film.

Ryan Coogler: Right on, bro. I appreciate you.

[music]

David Remnick: Director Ryan Coogler. The film Sinners comes out next week. Jelani Cobb is a staff writer at the New Yorker and he's also dean of the School of Journalism at Columbia University.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.