Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and the Confounding Politics of Junk Food

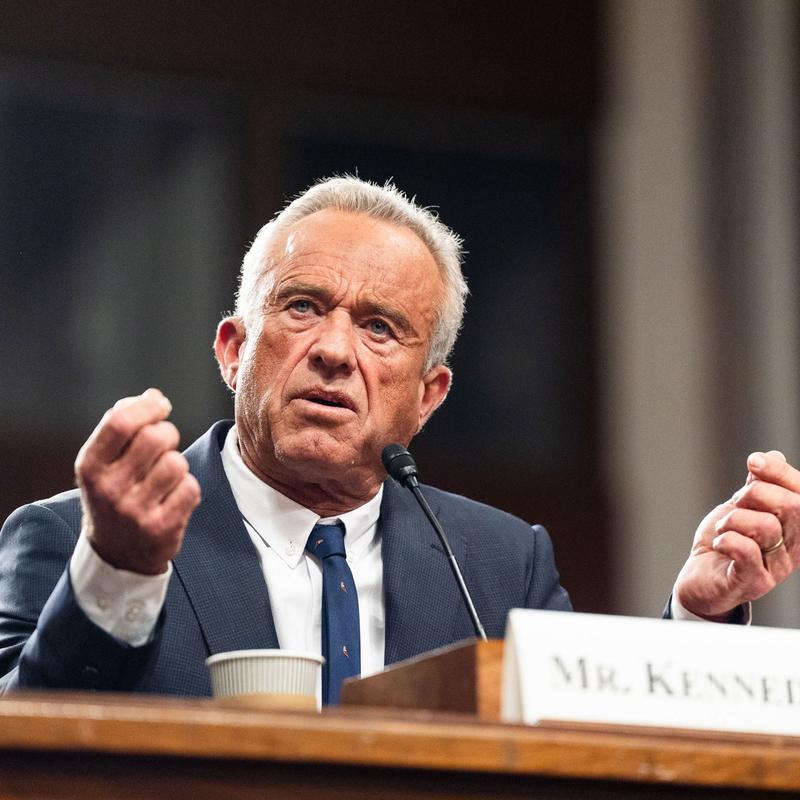

David Remnick: Last fall, when Robert F. Kennedy Junior was angling for a position in the second Trump administration, he introduced the slogan, Make America Healthy Again, MAHA. It riffed on MAGA, but focused on themes far more familiar in liberal circles, toxins in the environment, biodiversity, and healthy eating. It's all confusing. At the Department of Health and Human Services, Kennedy is undermining public trust in vaccines even during a deadly measles outbreak. He's overseeing massive cuts to research across American science, ending critical diabetes studies, for example.

Meanwhile, the FDA says it wants to curtail the use of certain food dyes, and Kennedy is talking about seed oils and processed food. Here's Kennedy recently in an interview with Sean Hannity that took place at a Florida burger chain.

Robert F. Kennedy Junior: All the science indicates that ultra-processed foods are the principal culprit in this extraordinary explosion, the epidemic we have of chronic disease. When my uncle-

David Remnick: Kennedy has put ultra-processed food or junk food, call it what you will, right into the political conversation. Now, you wouldn't necessarily expect this given his boss's devotion to fast food chains.

Donald Trump: It's not probably healthy, but I'm not sure I believe in that. You eat-- Who knows? They say, "Don't eat this food. Don't eat that." Maybe those foods are good for you.

David Remnick: The New Yorker's Dhruv Khullar is a physician, and he's been reporting on the American diet for The New Yorker.

Dhruv Khullar: When I started researching this topic, I knew that I wanted to talk to Marion Nestle. She really put on the map the ways in which politics and economics influence our food environment and ultimately our health.

David Remnick: Marion Nestle is a professor Emerita at New York University, and her books include Food Politics. She spoke with Dhruv Khullar.

Dhruv Khullar: I want to talk a little bit about Robert F. Kennedy Junior. He has many controversial claims, of course, on vaccines and other parts of health, but he is very concerned about ultra-processed foods and rates of chronic disease in this country. What do you make of the potential that he's going to drive real change in this area that's towards the good?

Marion Nestle: First of all, when President Trump tweeted that he was nominating RFK Junior for this position, he talked about the food industrial complex. I nearly fell off my chair. That sounds like me. I talk about the food industrial complex. The first thing that the president did was to appoint this high-level council, which is to write a report on the nutritional health of the population and how to prevent chronic disease. When I read that, I thought, "This is so exciting." My second thought was, "Wait a minute. I've seen this already. Didn't we already do this? Isn't this exactly what Michelle Obama did in 2010?"

Dhruv Khullar: That's what I want to ask you. The rhetoric seems to be there, but are we going to see the requisite action? What would that action even look like? If you were to counsel RFK Junior on how to actually make a dent on ultra-processed foods and the chronic diseases that are associated with it, what would you want to see him do?

Marion Nestle: Let me first state very clearly that nobody has asked me. I think what you have to do, first of all, is you have to put restrictions on the food industry. You have to stop the food industry from marketing junk foods to kids, ultra-processed, if you like. You got to stop that. Is RFK Junior going to take on the food industry? I'll believe it when I see it. When Michelle Obama attempted to do even much, much less than this just to get food companies to voluntarily stop marketing junk foods to kids, the pushback on it was extraordinary from exactly the people who are for it now. I'm glad times have changed. I want to see them do something.

Dhruv Khullar: What exactly are ultra-processed foods? How do we define ultra-processed foods when we're trying to study them?

Marion Nestle: You have to understand the background of this a little bit. That is, a professor of public health in Brazil, Carlos Montero, devised this concept in 2009. He divided foods into four categories, unprocessed or minimally processed foods, like corn on the cob or apples, or things that you just eat. A second category was processed culinary ingredients. By that, he means salt, sugars, salad oils, vinegar, the things that you cook with. Then the third category is processed foods, things that are frozen, foods that have been packaged, foods that have been cut and processed in some way, but they're really pretty simple. The fourth category is different. These are foods that have been industrially processed. The operating definition is you can't make them in your home kitchen.

Dhruv Khullar: I brought some groceries that I was hoping that we could go through together, and you can tell me whether they're ultra-processed and, if so, what is making them ultra-processed.

Marion Nestle: Did you? Okay.

Dhruv Khullar: Let's take a look here. What do we got?

Marion Nestle: Oh, Doritos, the prototype.

Dhruv Khullar: Doritos, I can probably guess which category this falls into, but just take a look and tell us what makes it ultra-processed.

Marion Nestle: This is the prototypical ultra-processed food because it started out with corn. Corn is the first ingredient. Does this look anything like corn to you? No.

Dhruv Khullar: Not so much.

Marion Nestle: Industrially processed. It's got real food in it. It has corn, vegetable oil, but then it has corn maltodextrin as the third ingredient. It's got things like whey protein concentrate, potassium salt, tomato powder, lactose, spices, artificial colors, lots of them, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate.

Dhruv Khullar: You don't have that in your home kitchen? [laughs]

Marion Nestle: I don't have that in my kitchen, and I cannot buy it at my local grocery store. These foods are processed to make them-- A lot of people use the word 'Addiction'. I'm a little uncomfortable with it, but there it is. The idea that that old Frito-Lays commercial, that you can't eat just one, that's exactly the point of these. These foods were deliberately designed to be profitable. That was their purpose. They weren't designed for public health purposes.

Dhruv Khullar: This is something that I would walk past in the grocery store and think, "100% whole wheat bread. This has got to be good. This cannot be ultra-processed." Tell me what you think.

Marion Nestle: Whole wheat bread is in, what I call, the conditionally ultra-processed category, because you can get whole wheat breads that are ultra processed, and you can also get whole wheat breads that are not. The ingredient lists. I love starting-- Whole wheat flour, nothing wrong with that. Third ingredient, wheat gluten, uh-oh. That's to boost the protein content. Sugar, yeast, fine. Vegetable oil, fine. Salt, fine. Preservatives, calcium propionate, sorbic acid, DATEM. Natural flavors, there's no such thing. Monoglycerides, monocalcium phosphate, soy lecithin, citric acid, vinegar, sesame seeds.

Dhruv Khullar: That sounds extremely ultra-processed.

Marion Nestle: Ultra-processed.

Dhruv Khullar: Why would they do that?

Marion Nestle: Two reasons. People like soft bread. People don't like whole wheat bread. Whole wheat bread is an acquired taste. It's very difficult for people. Humans have been making white bread for millennia because it tastes better. It's easier to digest. You don't have to chew it as much. This stuff is really soft, very, very soft. That's what the DATEM and these other things in there are doing. It'll sit on the shelf for a really long time. It won't get moldy.

Dhruv Khullar: What do we got here? We have yogurt. Most people would think, "Yogurt, that's pretty healthy." We have a very vanilla yogurt here, so maybe there's some trouble there.

Marion Nestle: What's this one? It's got cultured Grade A non-fat milk, yes. Water, yes. Modified food starch, sigh. Oh, it's got allulose, one of those indigestible sweeteners. Kosher gelatin, corn starch, citric acid. Where'd you find this? Sucralose, an artificial sweetener. Tricalcium phosphate, potassium sorbate. Oh, another artificial sweetener. This thing has three artificial sweeteners in it. Doesn't have any sugar. Doesn't say anything about the cultures. What you want in yogurt is you want all those friendly bacteria to make your microbiome happy. I'm not sure the friendly bacteria like all this stuff.

Dhruv Khullar: A yogurt that has a emulsifier or a thickener is surely not the same as a bag of Doritos or gummy bears, right?

Marion Nestle: No, it's not.

Dhruv Khullar: How do you help people understand that nuance? Is it like, "If you could make it at your home, but it has this one ingredient, it's probably okay."? Just trying to help us understand-

Marion Nestle: It is common sense. Everybody knows what junk foods are. When I talk about ultra-processed foods, everybody gets it right away. If you've got a yogurt in front of you and it's got M&M's added to it and it's loaded with sugar and it tastes like a dessert, you know that you're dealing with something that's ultra-processed.

Dhruv Khullar: Yes, but then aren't we just back at square one, where ultra-processed foods is a fancy way to say junk food?

Marion Nestle: Oh, sure. The point about the ultra-processed food classification is that people were able to do research. This research has been overwhelming in its consistency. Let me tell you. In nutrition, this is very unusual. It's unusual to have this level of consistency, where every study of ultra-processed foods shows that people who eat a lot of these kinds of things have worse health outcomes. The controlled clinical trials that show that these foods get people to eat more, not only more, but a lot more.

Dhruv Khullar: Tell us a little bit about the ways in which people have been studying this concept and why you think it's such a consistent story.

Marion Nestle: The observational research looks at what people self-report eating. All it can do is demonstrate association that if you eat a lot of ultra-processed foods, the chances are, and we're talking about probabilities here, you have a higher chance of gaining weight, becoming obese, having Type 2 diabetes, having heart disease later on. The problem with self-reports in nutrition is, I'm going to put this politely, people have a hard time remembering what they eat. Out and out, they lie.

To get around that, you need really well-controlled clinical trials. These are breathtakingly expensive to run because they require a locked metabolic ward facility in which people volunteer to be locked up for some period of time. Never more than four weeks because People can't stand it. Everything they eat, drink, or ingest is monitored, and everything they excrete is monitored. Their behavior and their physical activity and everything else is monitored, and they can't lie or cheat.

Dhruv Khullar: I had a chance to go to the NIH to observe one of these clinical trials recently, and it's hard to overstate how meticulously they go about doing things. Someone comes into the lab, every bite that they put in their body is measured. The chefs who are cooking the food, they are basically doing chemistry experiments in the kitchen to try to make sure that the amount of salt and fiber is exactly matched in ultra-processed and processed diets. When people were on the unprocessed diet versus the ultra-processed diet, on the ultra-processed diet, they ate 500 calories more each and every day-

Marion Nestle: On average.

Dhruv Khullar: -which is an enormous increase.

Marion Nestle: It's just an enormous-- Of course, they gained weight. They gained a pound a week. That's 500 calories a day, 3,500 calories a week. That's a pound. The people who were in the study didn't know which diet they were eating. Because they all tasted good, they liked the food. The chefs must be unbelievable. Then the big heavy criticism of the study is that it's too short and that there would be regression to the mean later on, and that's possible. I tell the critics, "Great, go ahead and criticize, but why aren't you fighting to get him more money to do longer studies with more people?"

Dhruv Khullar: The headline finding here is that ultra-processed foods tend to make people eat more than they otherwise would. It seems there might be two reasons for that. One is hyperpalatability, and so the combinations of sugar and fat-

Marion Nestle: Yum.

Dhruv Khullar: Exactly, yum. These combinations of things that you don't often find in nature, but you find in ultra-processed foods in high quantities, people can't eat just one, as you said. The other big driver seems to be calorie density. For every bite that you take, there's just many more calories per bite, of course. You're going to tend to eat more, and your body may not have time to realize it's full before it's already consumed many more calories. You could envision ultra-processed foods doing a number of other things to the body.

One is changing the microbiome. Maybe the microbiome changes in interesting ways. You process food differently than you would on a more natural diet, let's say. Two is changing the endocrine system in some way. The hormones that help us regulate how full we feel and how our body responds to food. The third is our taste buds. If you're getting big hits of salt and sugar, and fat, your taste buds are going to adapt in a way that they want more of that over time.

Marion Nestle: We know that works with salt. We absolutely know that, and with sugar. Those are difficult theories. I like simple explanations. The simple explanation is these things just are so yummy that people can't stop eating them. When you're eating a salad, you know when you've had enough salad. You've got a bunch of Oreo cookies in front of you, "Well, I'll just have one more. They're small."

Dhruv Khullar: I want to ask you about the dietary guidelines.

Marion Nestle: Go ahead.

Dhruv Khullar: A group of experts met in the fall to preview their recommendations for the next five years of dietary guidelines for the United States. That group of nutrition experts at least seem to say that we don't have enough high-quality evidence to make a strong recommendation against ultra-processed foods. I think they talked about some caution around processed meats, but they declined to basically tell people in a clear way that you should avoid ultra-processed foods. What did you make of that?

Marion Nestle: They deliberately excluded any consideration of the controlled clinical trials because they said they were too short. They were completely dismissed as if they never existed. All of the studies that they looked at were either animal studies or observational studies, and on that basis, they said, "We can't make a decision about it." I thought that was a very weak recommendation. I was very disappointed.

Dhruv Khullar: What do you make of some of the other ideas? I'm thinking about things like no ultra-processed food in schools. I'm thinking about taxes on certain types of foods or food additives, changing the subsidies to corn and soy, for instance. What do you make of those proposals?

Marion Nestle: I'm for all of those. I think if we're really going to change the food system, the first thing we have to do is get money out of politics, but that's a little off topic. [laughs]

Dhruv Khullar: [laughs] Got you. As I understand it, there's what I call the Vitamin Era around the Great Depression and the World War II. There's the Nutrient Era, maybe mid-century to the 90s, where people are focused on individual nutrients. Then, more of a dietary pattern era, maybe we've been in that one since the 90s. How does ultra-processed food fit into that framework, if at all?

Marion Nestle: That's my trajectory. The first thing I was interested in was vitamins. I love them all. They're all so interesting. Each one is different. They do different things in the body. To me, they were intellectually fascinating. I just adored them. Then I realized that people don't eat vitamins, except people who take supplements. They eat food. Food is really complicated. Eventually, I thought, "Wait a minute. People don't eat food. They eat diets. They're eating lots of different foods. These foods interact in different ways."

The basic principles of nutrition are, try to eat as much of a variety of real food as you can. The big change was the shift from not having enough nutrients to having too many calories. Then, in 1980, the inflection point, when President Reagan was elected, and lots and lots of policy changes took place. Then rates of obesity, the prevalence of obesity started to rise very, very rapidly. The reasons for that, I think, are pretty well understood. People ate more. There's tons of evidence that people started eating more in the 1980s, portion sizes got larger, a sufficient explanation.

Dhruv Khullar: Marion, you're someone who's probably thought about this more than anyone that I know. What's your relationship to food? How do you make the right decisions?

Marion Nestle: I love it. [laughs]

Dhruv Khullar: How do you choose the right foods?

Marion Nestle: I like real food. I have my favorite junk foods, and I eat my favorite junk foods. I just don't eat a lot of them.

Dhruv Khullar: Marion, this is so helpful. Is there anything that I haven't asked about that you want to make sure that we get to or that you want to add?

Marion Nestle: Just that this is such an interesting time in American politics. I think it would be wonderful if RFK Junior could make the food supply healthier. I just think that in order to do that, he's going to have to take on the food industry, and I don't think Trump has a history of taking on corporations of any kind. We'll see. Maybe he'll get them to volunteer. Maybe he'll be able to do what Michelle Obama was unable to do because of the opposition.

Dhruv Khullar: I guess time will tell. Thank you.

Marion Nestle: Lively.

Dhruv Khullar: This was great. This was a lot of fun.

Marion Nestle: You're fun to talk to.

Dhruv Khullar: I appreciate it.

David Remnick: Marion Nestle is a nutrition researcher and the author of books, including Food Politics, which is also the name of her blog. Dhruv Khullar is a physician and a contributor to The New Yorker. Now, after they spoke, one of the NIH's top scientists studying ultra-processed food, Kevin Hall, left the agency. Hall says that he experienced censorship. He wasn't allowed to speak to the media about research results that did not support what he called, "Preconceived HHS narratives". A spokesman for the department told CNN that this was a deliberate distortion of the facts.

[MUSIC]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.