The City of Minneapolis vs. Donald Trump

David Remnick: It was just over a week ago that Donald Trump announced to the world, "Sometimes you need a dictator." He's made a dictator joke before, but this was no joke. It was a simple statement of how Trump views democracy and the rule of law as hindrances to asserting his own will over the nation and the world. Trump made the dictator remark at the World Economic Forum in Davos as he was threatening to seize Greenland from Denmark and end the post-war order.

Back home, we were looking at quite another side of the same coin. An American city, Minneapolis, seemingly in a state of siege. Federal agents were going door to door, demanding identification from people on the street, and detaining those who got in their way. Renée Good, a poet, had already been killed, and others had been wounded, but that did nothing to moderate their tactics. Then Alex Pretti, a nurse, was shot and killed in a hail of bullets after he came to the aid of a protester.

The administration did what, frankly, a dictatorship does. They said that Pretti, who had been carrying a licensed firearm that he never brandished, was, in fact, a terrorist, an assassin, and they justified the killing. We're going to talk about Minneapolis today and what it bodes for this country. Emily Witt and Ruby Cramer have been reporting from the city, and I spoke with them this past week. They're both staff writers for The New Yorker.

[music]

David Remnick: Emily, you reported on the protests in Los Angeles last summer. Now, you're in your hometown of Minneapolis. How have the ICE strategies changed from LA to Chicago to what we're seeing now in Minneapolis?

Emily Witt: Well, the biggest difference is just the number of agents relative to the size of the population. In LA, I don't know exactly how many people were deployed there. LA is an enormous city, and they were spread out all across LA County, which takes hours to cross from one side to the other. It wasn't the same sense of, really, agents everywhere in the very heart of the densest part of the metropolis.

David Remnick: What was the difference in atmosphere, if any?

Emily Witt: The protests in Los Angeles were really concentrated around Downtown LA, and the confrontations there were between local law enforcement and demonstrators. Even though there were people following around ICE agents, you didn't see the same face-to-face confrontation between just ordinary people and federal agents with the same degree of intensity that you're seeing in Minneapolis.

David Remnick: Ruby, you interviewed the mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, and you spent quite a lot of time with him. He's a very young mayor when he took office. His first term, of course, was defined by the murder of George Floyd. Now, he has this in front of him. That's a lot of trauma for one city. That's a lot of politics for one city. A lot of violence. Let's listen to a bit of your conversation with him.

Mayor Jacob Frey: I fill potholes. I try to make the streets safer. I put up affordable housing.

Ruby Cramer: Yes.

Mayor Jacob Frey: We do ribbon-cuttings for affordable housing.

Ruby Cramer: Right.

Mayor Jacob Frey: We pick up the trash. That's what I do. That's what we want to do. That's our goal here. Our goal is like, "Would you lay off and let us have this comeback we're experiencing?"

Ruby Cramer: Right, right.

Mayor Jacob Frey: Just allow us. We're not even asking for money.

Ruby Cramer: Right.

David Remnick: A mayor who just wants to fill potholes, pick up the trash, and then he's talking about this comeback that he wants to be experiencing. What is he referring to, Ruby?

Ruby Cramer: He feels as if Minneapolis was in the midst of a renaissance, in his words, before this happened. Crime in nearly every neighbor in Minneapolis was trending downward. Frey, when he came into office, was a candidate who had a passion for housing. Housing was his biggest issue. As you said, his first term became defined by something completely different. Issues of racial justice, police reform. Now, he's in the midst of the very first weeks of his third term, which he said is going to be his last. He's dealing with a completely unprecedented situation. I think he told me multiple times, this is the first time anything like this has ever happened in an American city.

David Remnick: In an American city.

Ruby Cramer: Yes.

David Remnick: I don't see how he's wrong.

Ruby Cramer: Yes, and I think it goes to what Emily was saying about just the presence of the federal force. The occupying force, as he said, is so deeply and viscerally felt in the city because it's such a small city. It's such a small target for such a large operation.

David Remnick: How did the response to the George Floyd protest shape what we're seeing now?

Ruby Cramer: I think the biggest impact is the local law enforcement element. This is a city where there's a police force of about 600 officers, so 600 officers to 3,000 federal agents. You already have a city where people feel that there's still trauma between the local law enforcement and protesters and the constituents of Minneapolis. Now, that local law enforcement force is the first line of defense in a lot of their eyes against this federal occupation. It's complicated. I've seen at these protests, a lot of anger erupting between protesters and local law enforcement. At the same time, the city is asking, 'How can we build empathy for our police force?" They're also in this impossible situation.

David Remnick: Emily, you grew up in Minneapolis. What do you think it is about the city, or maybe it's just happenstance that made it the site of now two of the largest protests in modern history.

Emily Witt: Well, it's an unapologetically, really progressive, leftist city. You've seen from the politicians that Minnesota is sent to the national stage, even going back to Paul Wellstone, people like that. It's a place that really values progressive ideals, and that isn't scared to be ambitious in its social goals. The people here are really civic-minded. People are in block associations. They're in community organizations. The city loves its parks. It's almost obsessed with its own community-minded practices. It's an idealistic place and a very sincere place. I think you see how those ideals, in moments of great drama, end up coming out and bringing people out and expressing their politics in the streets.

David Remnick: Well, if the administration's goal was to deport undocumented immigrants from the United States, is Minneapolis a place that you would put high on the list to deploy such a force?

Emily Witt: No. If this was really about immigration and not about political punishment, as it seems to be, Minneapolis's undocumented population is something like 2.2% of the state's population. I think it's around 100,000 people. No. If that's the problem you're claiming to fix, there's states with much bigger undocumented populations, especially relative to the size of force that they've brought into the state.

David Remnick: Well, if it's political punishment, what's being punished?

Emily Witt: Well, the governor of Minnesota, Tim Walz, was the vice-presidential nominee. It's a place that Trump has never won here. He's come pretty close in the last election. He lost by about four points. The state overall is pretty divided politically, but Minneapolis is really, really not. It's overwhelmingly Democratic. Yes, his political rivals seemed to be here. The head of the DNC comes from Minneapolis. Yes, Walz was a national political figure on the left that now his career seems to be winding down.

David Remnick: One of the factors seemed to be a fraud investigation. Give us a straight-up summary of the reality behind the fraud investigations, which seems to be a source for the administration's hostility, especially to the Somali immigrant community.

Emily Witt: Yes, so since the pandemic, there was a widespread fraud in Minnesota's social benefits network, especially one nonprofit in particular called Feeding Our Future. That fraud has been under investigation by federal prosecutors for a couple of years. They've convicted more than 60 people. A majority of those people have come from the Somali American community.

The person that prosecutors described as the mastermind of the thing was not Somali American. She was a white lady from Minnesota. Trump has made this fraud an immigration issue, even though an overwhelming majority of Somali Americans all across the country are American citizens, either by naturalization or birth. He's turning something that was just some bad actors into an immigration story and using it as an excuse to come here to Minnesota in particular.

David Remnick: Trump is often invoking the name of Ilhan Omar, the congresswoman, a Democrat, obviously, and trying to make her a central figure in this conflict somehow. Just the other day, she was attacked while speaking. Somebody took out a syringe and squirted some unknown fluid at her, which was certainly scary in the moment. What does Ilhan Omar have to do with this directly?

Emily Witt: Well, I think it's pretty clear that the president likes to go after certain people he feels he can other in some way or another. Omar's been elected. She's in her fourth term. She's seen as a leader here. Obviously, her constituency supports her. He wants Minneapolis to turn against people in their community that they see as their neighbors and their leaders and their fellow residents of the city. He wants them to turn against them. You see that with his going on about the fraud. You see that with his attempt to demonize Ilhan Omar. He wants to divide the city against itself, and the city is refusing to accept that narrative.

[music]

David Remnick: I'm speaking with staff writers Emily Witt and Ruby Cramer. We'll continue in just a moment.

[music]

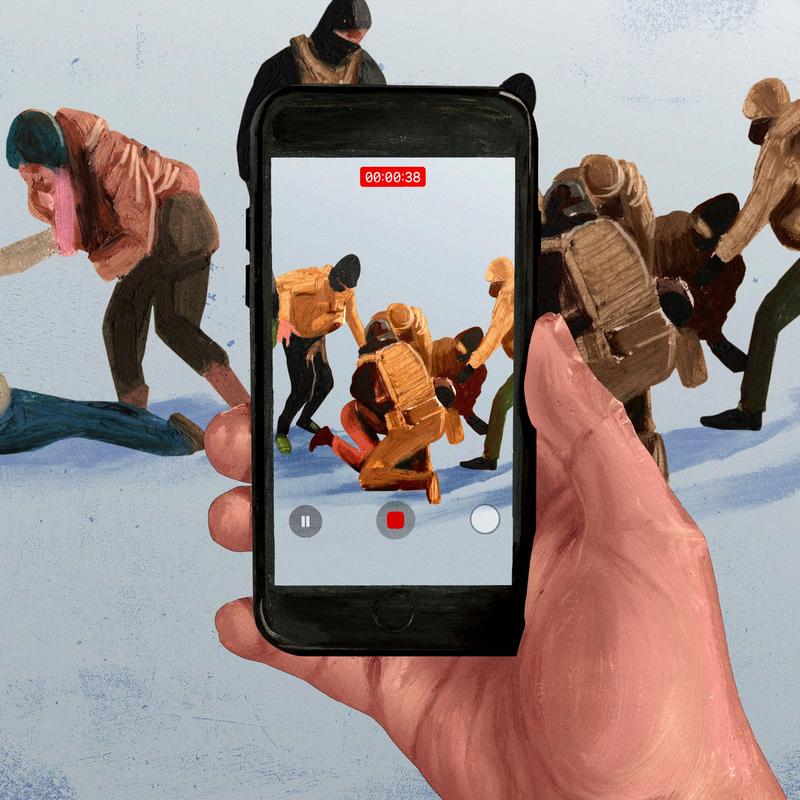

David Remnick: We're talking today about the overwhelming federal force in Minneapolis, the repressive tactics, the violent results, the administration's response. It's all been described as an immigration enforcement surge. Surge. That resonant military term is hardly inappropriate. The operation ordered up by the president and carried out by heavily armed, often undisciplined federal agents is ostensibly an immigration operation, but it also seems intended to intimidate an entire American city.

The spectacle, the dark reality, is of Minneapolis under siege. I've been speaking with Emily Witt, who wrote The Battle for Minneapolis for The New Yorker, and Ruby Cramer, who wrote The Mayor of an Occupied City about the city's mayor, Jacob Frey. Pam Bondi, the attorney general, recently said that she wanted access to Minnesota's voter rolls and its welfare data. If she got that, maybe she'd pull out some forces, some ICE forces from the state. What do you make of this?

Ruby Cramer: I think it's what Emily has said, what the mayor has said. We're seeing evidence that this directly has to do with political retribution. Now, we see Pam Bondi, who's basically been the leader of Trump's effort to go after his perceived political enemies, now coming to Minneapolis and saying, "If you do this," related to voter rolls, I'm not sure what that has to do with the surgeon, what they're trying to accomplish with immigration on the ground in Minneapolis, "we'll do X. We'll pull out."

David Remnick: What do we know at this moment about the killing of Renée Good, and what do we know about who killed Alex Pretti? In other words, how far along are, at least, the preliminary investigations into those killings? Is the state of Minnesota even able to investigate?

Emily Witt: Yes, those investigations have been stymied. The Department of Justice has said they won't conduct a criminal investigation into Renée Good's death. With Alex Pretti, we don't know the name of the agent or agents who shot him. The Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which is the local law enforcement body that investigates this stuff forensically, has had its access denied. They haven't been able to see the evidence. They're not confident that the evidence hasn't been tampered with or destroyed in some way. There's a real fear here that these killings won't receive a good investigation, and that the people who committed them, there won't be any inquiry into what they did.

David Remnick: Well, the amazing thing is that the vice president of the United States, JD Vance, declared after the killing of Renée Good that ICE agents have, and this is his quote, "absolute immunity," a comment that he's tried to walk back a little bit since then, but not with great success. Do you think that's affecting what's happening on the ground and the tension and the anger, Emily?

Emily Witt: Yes, absolutely. Certainly, the behavior of the agents. It appears they believe they have absolute immunity, just in terms of not only the people they've killed, but the way that they're treating protesters, insulting them, spraying them in the face with pepper spray.

David Remnick: Sorry to interrupt, but I get the feeling that all of our listeners are a little bit like me. In other words, we get to watch snippets of this on social media or a five-minute report on cable news or something like that. What I'd love to know from both of you is what it's like to stand there in the freezing cold and watch a bunch of ICE officers and a bunch of protesters facing off. What's the feel of that? How do the tensions get ratcheted up? What's the vibe between those two people, and how it leads to violence? Ruby, maybe you could start.

Ruby Cramer: They've been very careful. I would be more curious for Emily's take on this because she's seen more of it, but people have been very deliberate. I think there's been such an effort by the Trump administration to cast these protests as very unruly and violent and referencing back to the riots after George Floyd's killing in 2020. What I saw was protesters that were very deliberate. We're feeling lots of things, but we're very careful not to cross lines.

Emily Witt: Yes, I would agree. The people out on the street are really there to observe the actions of ICE. They're not trying to get into a skirmish with federal agents. They might be yelling things at them, but they're not trying to start fights. They're not breaking windows for the most part. What I'm seeing on the streets here is a calm, determined anger, real anger--

David Remnick: There are no outliers. There are no people that are particularly provocative among the protesters in your experience?

Emily Witt: No, I think one thing is Minneapolis saw how its anger-- what happened to George Floyd was turned against it in the national political narrative. I think there's a sense they're not going to play into any narrative that-- and they're being called domestic terrorists and agitators and professionals, all this stuff, and they're refusing to present themselves that way. I really haven't seen exceptions to that when I'm out in the streets.

David Remnick: Ruby, there's a relatively new chief of police in Minneapolis. His name is Brian O'Hara, and he started in 2022. His position is, needless to say, excruciating. Let's listen to a little of your conversation with him about dealing with the influx of federal agents.

Brian O'Hara: It doesn't appear that there's much effort to de-escalate. We come into chaotic situations. The training for several years has been to be proportional, to be professional, try and slow things down. You come into a situation where there's some minor offense that may be offensive to you as a professional. You're not supposed to take things personally, even if someone's yelling something at you. The problem is, especially with some disorderly conduct, if you step in as a cop and you start up here and they don't comply, there's nowhere else to go but up.

Ruby Cramer: Yes, true.

Brian O'Hara: It just doesn't make sense. It makes your own job that much more frustrating and difficult.

Ruby Cramer: Right.

Brian O'Hara: It's in no one's best interest.

Ruby Cramer: Maybe that's also where some of the confusion comes. It's just like everything's just like--

Brian O'Hara: I saw one video with a woman who was saying she was disabled, where one officer goes through the open window. While he's through the open window, another officer is trying to open the same door. Someone else on the other side is breaking a closed window. They're pulling her out while she's still in her seat belt, saying that I'm disabled. There's at least two knives that are out because they want to cut the seatbelt. It looks like complete chaos.

Ruby Cramer: Yes.

Brian O'Hara: I don't know how anyone can see that and think that is safe for anybody involved.

Ruby Cramer: Right.

David Remnick: Ruby, at the end there, he's referring to an incident that everybody here watched on cable news and social media. This woman being pulled out of the car with terrific force, I would say. Here, you have the chief of police in very measured terms, but nevertheless, speaking oppositionally to these federal forces. There must be enormous tension between the Minneapolis police and ICE.

Ruby Cramer: It was remarkable, actually. I was sitting in his office at the police at City Hall. To hear a police chief speak so critically and in such a detailed way, too, about fellow law enforcement, even though they're different agencies and they're on opposite sides of this conflict, I'd never quite heard somebody be that critical law enforcement to law enforcement, right? I thought that was remarkable. There is tension. There's confusion among the police about what these agents are trying to accomplish.

I think in that clip that we just heard, Brian O'Hara was specifically referencing that incident, but he was breaking it down movement by movement, like, "Now, you see one agent doing this, and then they bring out knives. What are they bringing?" I think everything in his training from his decades as a police officer was telling him, "Nothing about this made sense," which is kind of crazy.

David Remnick: Didn't Brian O'Hara, the chief of police in Minneapolis, wasn't he involved in a program in Newark that informs his experience and his point of view?

Ruby Cramer: Yes, he was involved in a police reform program in Newark, and he'd been in Newark for his entire career. Came to Minneapolis in 2022 to help reform the department, inherited a department that was losing officers or had been losing officers. He was trying to build it back up. It was understaffed, essentially. On top of that, all the officers that he had that had been working in 2020 had some form of stress or trauma or anxiety.

That's now, he said, being reactivated. He used the word "triggered." Again, I've never heard a policeman use this language, but he was saying all these old wounds are being triggered. He's really worried about a mass exodus from his department. He told me, in his department of 600 officers, 100 of them are retirement age. He's like, in theory, if this gets bad enough, 100 people could leave.

David Remnick: Walk out the door, yes.

Ruby Cramer: Then what would they do?

David Remnick: Ruby, there's a lot of talk now about how local government is or isn't helping the federal government. It's been a challenge for local government to navigate how to work under these conditions. They're practically unique. Let's listen to a clip of the mayor of Minneapolis from when you interviewed him, talking about how his government typically works.

Mayor Jacob Frey: In normal times, we work with every government out there. That's the expected norm. The expected norm is that our Minneapolis police work with the Hennepin County Police. We work with the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which is happening, by the way. We work with the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which, of course, happened. We work with State Patrol, which is happening. They also work with the Feds on a number of-- and you expect there to be a partnership when something goes down that's serious or an emergency.

When bad things happen, you expect partisan divides to be eliminated and for people to come together. The 35W bridge is before my time here. When the 35W bridge collapsed, you had a president who was not wildly popular in this city, in Bush, come here. The politics stopped at the water's edge, and everybody did their part. Money was issued, and support was provided. It was a team. It didn't matter what party you were on. Political retribution was never a phrase that was even considered, let alone uttered, let alone enacted.

David Remnick: Now, Trump has been saying during this crisis that local government refuses to work with the federal government on immigration. What's the truth or not in that?

Ruby Cramer: Frey was telling me that he had had virtually zero communication with the federal government. This was before the shooting of Alex Pretti. Since then, he's had conversations with Tom Homan, who's now taking over the operation in Minneapolis. He has spoken to the president as well. I think what you're hearing a little bit in that tape is Frey, the realization hitting him over and over and over again, that he was locked in a war with his own federal government, and that the city was being overwhelmed by the federal government, and that the federal government, rather than being a partner of any kind, was a hostile force that was felt all over the city. Eventually, he himself was learned that he was the subject of a criminal investigation by the DOJ, so then he personally felt like he was being targeted by the federal government.

David Remnick: The DOJ was investigating the mayor of Minneapolis?

Ruby Cramer: The DOJ is allegedly investigating whether the governor and the mayor have colluded in a conspiracy to obstruct immigration operations in the state of Minnesota.

David Remnick: That's pretty incredible, no?

Ruby Cramer: Mayor Frey learned of this through the news like everybody else and, the next morning, proceeded to go on about four Sunday shows. They were all asking him, "What's this about?"

David Remnick: "What's up with that?"

Ruby Cramer: "Do you have any information? Have you gotten served a subpoena? What's going on?"

David Remnick: Nothing.

Ruby Cramer: He didn't know anything. It was surreal. It was just another layer of unreality to this whole thing.

David Remnick: Emily, you spent time with some people who are trying to keep their communities safe. You rode around with two people in particular who were trying to spot ICE on the streets of Minneapolis. Many of us have heard about this kind of effort, both in Minneapolis and in other cities. How does it work, and what did you see on that ride?

Emily Witt: Yes. Minneapolis is activated in all kinds of ways. One of them is people who go out in their cars, and they'll call into a signal chat that has a dispatcher. They ride around their neighborhoods and look for suspicious vehicles, which are often American-made SUVs with tinted windows and out-of-state plates. They'll call in a license plate. The volunteers keep a database of known agents.

If they ID it, the idea is they follow a safe distance. They just want to be there to record some of what we've been seeing. Because the government is not really telling us who they're taking and where and how many people with any specificity, they want to make sure somebody's bearing witness to that, and also just drawing attention, perhaps to help some of their neighbors have time to lock their doors or get somewhere safe as the agents are moving around the city.

David Remnick: You spoke with two ICE observers who ended up themselves being detained. A woman named Patty O'Keefe and a guy named Brandon Siguenza. We're going to listen to a little of Brandon Siguenza describing this situation.

Brandon Siguenza: I passed by a cell that was full of people that there was no room to lay down, so they were either standing or sitting in it. People were staring at the wall, staring at the floor. A man had his face pressed up against the observation glass, I think, just trying to look out and get some stimulation. I passed a bathroom cell that was a two-way mirror so I could see into it. The woman, whose bottom half was covered by a concrete barrier, she was on the toilet crying, and then on the near side of the concrete barrier was a seat.

There was another woman, who I assume was her family member, but I don't really know. It was scream, crying, and yell. I can't forget the way it sounded. It was horrible. The bathroom I was brought to was covered in urine. Toilet paper was wet. There's no soap. I get many thoughts like, "This is how they're treating me, a US citizen, white-passing man." I can only imagine what's causing all these people to be sobbing and screaming and begging.

David Remnick: Emily, how long was he in detention?

Emily Witt: About eight hours.

David Remnick: What about the accounts of the time in detention was most surprising to you?

Emily Witt: I was very surprised that the person we just heard from was interrogated as if he were not just a person out exercising his right to observe and protest, but someone who was part of an organized network of bad actors. He was just baffled. Both of the people I spoke with were genuinely surprised that the people interrogating them believed their own narrative about who was doing this, I think.

David Remnick: Let's focus a little bit on those interrogations. Both Brandon and Patty O'Keefe describe what those interrogations were like. Let's listen to them talking about that.

Patty O'Keefe: They also asked, "Do you know of any protesters that are planning any violent things or might be capable of planning violent actions?" I was like, "Well, what do you mean by violent actions?" They're like, "Well, say, like creating maybe or making plans to set off a bomb or potentially snipe ICE agents." I just responded, and I was like, "A bomb? [chuckles] Are you kidding me?" I was like, "You guys are way too afraid of us. No, I don't know of anyone doing that."

Brandon Siguenza: This is my speculation, but they think we're in cells with commanding officers in military barracks. Like, "I'm just a teacher, man." [sighs] He thought we were some kind of paramilitary organization of some kind. I don't know. That's my speculation. I don't know for sure. Yes, so he said that, and I was confused and like, "Bro, who do you think I am?" [chuckles] Then he was like, "Yes, we can help you out in other ways."

I kept asking specifically, like, "What are you asking me to tell you? What are you offering me right now?" He's very vague unless I press him. Then, at one point, I was like, I think reacting to the bombs and stuff, he's asking about bombs. I'm like, "I'm just trying to protect my neighbors." He said, "Oh, your neighbors? Where are they from?" Thinking I meant my next-door neighbors, not my community.

Then he asked me if I knew anyone that was in the country illegally. He wanted the names of people. That's what he wanted. He wanted the names of protest organizers. He wanted the names of undocumented people. What he was offering me, he said, "If you have family that's out of the country that needs help getting in, we can help with that." I'm Hispanic. At one point, I was like, "What is it exactly that you're offering me?" At one point, he was like, "Money." Offered me money, which was surreal.

David Remnick: "Surreal" is the word for it in this interrogation. According to him, he was being offered money. At the same time, he's being intimidated. He's being offered immigration help for, potentially, some of his relatives. Was that surprising to you? Did you hear that elsewhere around town?

Emily Witt: He's the only person that I heard that from. I should say that the Department of Homeland Security said that no money was offered. Yes, it is surreal, and yet I do think the federal authorities believe in this kind of story they're telling of an organized resistance to them that might be armed. I think you see that in the really trigger-happy response of the agents that are out in the streets.

David Remnick: There is a startling contrast between Minneapolis in the summer of Black Lives Matter and the murder of George Floyd to now. It just seems a markedly different approach to protest and resistance, or am I getting that wrong, Emily?

Emily Witt: No, that's totally correct. I think it's just a really different situation. In that case, the city was expressing rage. Minneapolis has long-standing racial inequalities, a long history of police violence against Black people. The city, in many ways, was expressing rage against itself and its own institutions, the only way it was able to. This is such a different situation. Why would you go around breaking the windows of your own city when it's being occupied from an external force, which is the sense of what's happening here. Right now, there's a sense of protection and mutual aid and taking care of each other. The anger is directed toward a much more external actor.

David Remnick: Ruby, are the police having to reconceive of their role at all? Apropos of your conversations earlier with the head of the police, how are they thinking about enforcement differently from the militarized forces on the ground?

Ruby Cramer: I think that they are walking a very, very fine line. The Minneapolis Police Department has a policy in place that says they will not participate with immigration enforcement, including even if--

David Remnick: There are direct odds with them?

Ruby Cramer: Correct. One element of this policy is even that they will not help with crowd control solely at the request of an immigration enforcement body. You'll see local police on the outskirts of protesters being tear-gassed. There's one video I'm thinking of where, in this case, it was a state trooper. A line of state troopers were standing, watching a situation like this unfold.

You can literally see tear gas in the air. A man taking the video is yelling at the state troopers, saying, "Aren't you guys on our side? Why are you just standing there and watching?" I think local law enforcement, basically, they're actively not participating in the immigration enforcement, but they're also not inserting themselves between protesters and federal agents. You'll see them on the periphery. I think it's been really challenging. I think they're still trying to figure out how to navigate this.

[music]

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm speaking with staff writers Ruby Cramer and Emily Witt. We'll continue in just a moment.

[music]

David Remnick: Staff writer Emily Witt is on the ground in Minneapolis right now, and Ruby Cramer recently reported from there on how the city's leaders are coping with what looks very much like an occupation by the federal government. The killings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti have galvanized a national backlash against Trump's immigration tactics. The chief judge for the Federal District Court of Minnesota identified 96 court orders that ICE has violated in January alone. Donald Trump is making noises now about backing down or backing off, but this is a fast-moving situation. Things are changing day to day, including negotiations over the federal budget in Congress. I spoke with Emily Witt and Ruby Cramer this past week.

[music]

David Remnick: Emily, you quote Congresswoman Ilhan Omar in your piece from a hearing in January, January 16th. Let's listen to a clip from that.

Congresswoman Ilhan Omar: We do believe that one of the reasons why he sent this paramilitary occupation into our state, why this level of terror is taking place, while we are seeing the kind of chaos that is ensuing, is because he does want to invoke the Insurrection Act. We are telling our constituents not to take the bait. We are telling our constituents to lawfully practice their First Amendment right. We are telling them to document, and we are telling them to fulfill any lawful orders that they might get from law enforcement.

David Remnick: That's Ilhan Omar. Of course, the governor, Tim Walz, has said pretty much the same thing, and yet people holding their phones are getting killed. Is there anything against the law about recording things on the street, taking out your iPhone, and filming the police or ICE?

Emily Witt: No, that's protected by the Constitution. That's constitutional. You can swear at an ICE officer. You can record them. You can express your discontent in any way that feels appropriate to you that's from a distance and nonviolent.

David Remnick: Now, Alex Pretti was carrying a legal firearm, but he was carrying a firearm. That has become a major element in the rhetoric against him by any number of people in the federal government. Ruby, how do we square that? There's a Second Amendment issue as a political issue. How do you think about this?

Ruby Cramer: I think people have said very rightly that it scrambled the gun debate a little bit. Normally, we're used to seeing conservative elements of the Republican Party come out and say people have a right to be armed and, if they have their permits, concealed carry at a protest.

David Remnick: We should say here that his firearm was taken away. He never reached for it. He was holding a cell phone.

Ruby Cramer: Exactly.

David Remnick: I'm not saying this is without complication, but those are the facts, too.

Ruby Cramer: He never reached for it. I think, now, we have video forensics that show quite literally, frame by frame, that not only did he not reach for it, but the gun was removed by one federal agent, and he was disarmed.

David Remnick: Yes. Let's look ahead a little bit here. Right now, you're starting to sense that the president of the United States, no matter how much he may endorse the original action, is seeing that it's a political problem for him. What do you expect from Washington in the coming days, Ruby?

Ruby Cramer: President Trump seems to be pulling back elements of what's been going on in Minneapolis. We saw Gregory Bovino, who is a Border Patrol agent with the title Commander at Large and would be the face of these operations, has been the face of these operations, removed from Minneapolis. He's been sent back to his post.

David Remnick: His social media has been taken down.

Ruby Cramer: [chuckles] His social media has been taken away. The sign that anyone's done. We have Tom Homan coming to take the operation over.

David Remnick: Tom Homan is the figure of assurance in this picture.

Ruby Cramer: Exactly. I think many people have said, "Well, he's not exactly been a moderate voice in Trump's administration." I think that's true.

David Remnick: Emily, what are your feelings on it?

Emily Witt: Yes, I don't think they're dialing it back. Our photographer was out yesterday and saw two immigrants get detained. They're talking about building more permanent housing at Fort Snelling to house the people that are stationed here. They're changing their tactics out there using smaller vehicles. It doesn't feel like it's stopping. They may be changing the rhetoric and bringing in slightly less flamboyant people to lead things. I don't know. I don't know how this sustains itself in the long term on either side, though, because people aren't working. People are staying home. People aren't going to the doctor. They aren't going to school. The city's really been in a state of emergency now for weeks, and it's exhausting. People are really tired.

David Remnick: How many undocumented immigrants have been swept up in this surge in Minneapolis and beyond?

Emily Witt: They're saying something between 2,500 and 3,000 were the last numbers that I heard as of mid-January.

David Remnick: What becomes of the 2,500 or 3,000 undocumented immigrants?

Emily Witt: We have a lot of journalism still left to do, I think. The reports are people here are being taken and then sent very quickly out of state, it seems like most often to Texas. If somebody knows they're detained, they can file a habeas petition and try to get them an actual hearing. From what I'm hearing, the conditions are really terrible. It's really cold there. The food is bad, all of that. People are having to wait two or three months to try to get your case worked out is torturous to people. A lot of people are considering deporting themselves, which I'm sure is the intention. It's just families here are having trouble getting in contact with their family members who are detained. There's not a lot of due process.

David Remnick: Let me go back to the beginning, Ruby. The mayor of the city said basically that the only way this ends is for Donald Trump to change course 180 degrees.

Mayor Jacob Frey: There is an action that he could take that would be quick and effective, which is to leave. It would be immediate. If he left, it's a light switch that immediately turns back on. Businesses are open. Safety is restored immediately. Mark my words.

Ruby Cramer: Yes, I don't see a way for the city or the state to hasten the end of this in any way. I don't think there's anything they can do. I think that's something that Frey was reckoning with. They have a lawsuit that's working its way through the process of federal court.

David Remnick: Who's suing whom?

Ruby Cramer: City and state officials in Minnesota are suing the Trump administration for an immediate stop to this surge of agents. They've made several arguments about why this is detrimental to the people of Minnesota. The federal government was just able to respond to that. Now, I think the judge is working her way through a decision and getting closer to doing that. Outside of that lawsuit, there's really nothing that these government officials can do.

David Remnick: Basically, the destiny of this situation is all in the hands of and in the mind of one guy, Donald Trump.

Ruby Cramer: Of Trump. Trump and Frey finally spoke.

David Remnick: How did that go?

Ruby Cramer: Apparently, [chuckles] Frey's account is that it was a productive conversation and that he very forcefully said, "This needs to stop, and people are suffering." I think he was probably trying to make the argument that this is not a popular thing. No one likes this, but at the same time--

David Remnick: Does the president show any evidence of much caring?

Ruby Cramer: We don't know, although--

David Remnick: It sounds like Frey's being pretty delicate in the way he's reporting this conversation.

Ruby Cramer: Yes, exactly. [chuckles] There's a lot riding on it, in fairness. I know that Trump has described it as a very good conversation. I know Frey was actually trying to go to Washington to have this conversation in person, so perhaps that could be on the horizon, too. Trump, since that "very good conversation," has also tweeted at Frey, saying, "If he does not cooperate with the federal government, he's 'playing with fire.'" It's back and forth and back and forth.

David Remnick: Emily, you're sitting right there in the city. What do you expect to happen next?

Emily Witt: I just don't know. It doesn't seem like the federal presence is diminishing despite some rumors that some agents were going to leave. I know people in Minneapolis are very tired. There's some fear that the sense of emergency will be lost, and all of this will become normalized, I think, is the fear. I don't know where it goes from here, except that I know that people here are very, very determined not to let up showing their discontent and their anger over what's happened here.

David Remnick: Emily Witt, Ruby Cramer, thank you for your terrific ongoing reporting from Minneapolis. I really appreciate talking with you today.

Ruby Cramer: Thank you so much.

Emily Witt: Thanks, David.

[music]

David Remnick: Emily Witt and Ruby Cramer are staff writers at The New Yorker, and they've been on the ground in Minneapolis. You can find their terrific reporting at newyorker.com, and you can subscribe to The New Yorker as well at newyorker.com.

[music]

Copyright © 2026 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.