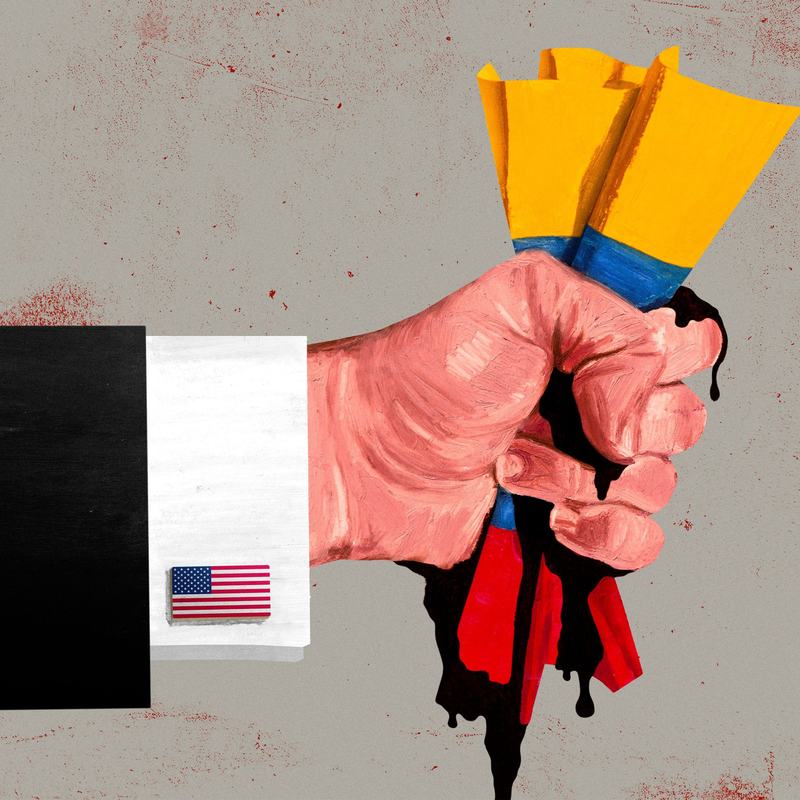

Trump’s New Brand of Imperialism

David Remnick: So many things about Donald Trump's presidency have been without precedent, but the US seizing power over a smaller country, well, there's a very, very long history of that. The American record of military intervention and adventure overseas, it goes back well into the 19th century and forward to Vietnam, Iraq, and beyond. In Venezuela, Trump has made no secret of his desire for oil revenues and who will be running the show.

President Donald Trump: We are going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition.

David Remnick: Daniel Immerwahr is a professor of history at Northwestern and one of our most interesting writers on foreign policy and American imperialism. His most recent book, a bestseller, was called How to Hide an Empire. At The New Yorker, he's covered subjects from 17th-century piracy to the seizure of Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro. I spoke with him last week.

[music]

David Remnick: Daniel, let's start with the events of the past week. They're astonishing. In your 2019 book, How to Hide an Empire, you wrote of the United States that even when it comes to oil, flare-ups of naked imperialism have been rare and haven't ultimately led to annexations. You wrote this during Trump's first term.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes.

David Remnick: What's changed?

Daniel Immerwahr: Exactly, that has changed. I described in the book, the passage from a desire for annexation as a form of projection of power, so claiming large territories to a more subtle form of power projection. Lots of military bases all over the map, other ways of exerting power. It seemed to me at that time that the age of colonial empire was not totally over. There are still some colonies, but really near extinction. It is extraordinary to hear Trump talk in a way that not only presidents haven't talked in decades, but I think presidents haven't even thought in decades of his desire to claim territory, to annex new places, Greenland, Canada, et cetera.

David Remnick: How would you describe the map of contemporary American empire, and what is it? We have military bases. I think not everybody's aware of it, just how extensive that map is. What does the American empire look like now?

Daniel Immerwahr: Okay, so there are five inhabited territories that are still part of the United States, and more than three million people live in them collectively. Puerto Rico is, by far, the largest, but then you're exactly right. Again, they don't quite appear on maps that we're used to seeing. Often, these places are secret, so you have to do a covert mapping of them. We think that the United States has about 750 military bases outside of the mainland. Most of which are in foreign countries.

David Remnick: That's amazing that you say "we think."

Daniel Immerwahr: We think, yes, we don't know. The United States does a basing report and does report on hundreds of those bases, but then there are hundreds more that we're just reliant on journalists to tell us about. There are a lot of edge cases, and a lot of we're not sure cases.

David Remnick: In the run-up to the Iraq War, you heard rationales coming from the Bush administration and elsewhere having to do with human rights. You even had former dissident leaders in Eastern Europe supporting it. Adam Michnik, Václav Havel, they were for this war from a human rights point of view. Then you heard rationales obviously having to do with weapons of mass destruction. It was an arms control situation. You would never hear someone in the Bush administration, whether you like them or not, saying, "You know why we're going in? Oil, because Iraq's got a whole lot of oil."

As the cliche now goes in Washington and elsewhere, it was saying the quiet part out loud. It was never said, except by critics. Now, you have a press conference on the morning after the invasion of Venezuela, where we've gone in militarily in a huge operation that had, by the way, been going on for weeks and weeks, but ends with the president of Venezuela being spirited to a jail cell in Brooklyn. While the people around Trump are mouthing these other rationales for it, Trump just gets up and says, "It's oil."

President Donald Trump: We're going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country.

David Remnick: There's no embarrassment about it at all. This seems, to me, something at least performatively new.

Daniel Immerwahr: Oh, it's totally. That's exactly right. We on the left, during the Iraq War, would play this game where we say, "Okay, the Bush administration is saying it's human rights." They have this story about weapons of mass destruction, but we don't believe them. We'd look for little reports of off-the-record statements where someone said something about oil, and we'd say, "Aha, that's the real thing. That's really what you want."

The reason is that the liberal international order, for good or ill, forced US leaders to say that they were doing things for impartial reasons, for reasons that had the good of the system in mind, because the whole point is that the United States had claimed to be an umpire in world affairs. You can't be an umpire if you say, "Well, I really would prefer that the Dodgers win." You have to pretend that you're above it all. The Bush administration would do that, and then its critics would say, "I don't really believe you. This game is rigged."

Yes, Trump has very little interest in the rhetoric of that. He actually sees it as a constraint and an imposition. That press conference was incredible because he did start out with a reason, right? It had to do with the importation of drugs into the United States. You could, I guess, maybe call that an act of war if you really wanted to. Then, just so quickly, that pretext just slipped away, and then he started talking about the oil.

David Remnick: I don't think he even argued the point that there are other countries who import far more by way of narcotics.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, no, because you can pick holes in that pretext very easily. Is Venezuela really the main concern if the concern is the importation of drugs? You got the sense that Trump just didn't care, like absolutely didn't care.

David Remnick: Now, in your book, How to Hide an Empire, you dug into America's interest in Greenland back in the mid-20th century.

Daniel Immerwahr: It's on the cover of the book.

David Remnick: Yes, so tell me a little bit about that because, suddenly, just days after the invasion of Venezuela, we have Stephen Miller, one of the closest aides to the president of the United States, talking about how we are going to exercise power the way it was exercised, and Greenland's next, quite possibly.

Stephen Miller: The United States should have Greenland as part of the United States. There's no need to even think or talk about this in the context that you're asking of a military operation. Nobody's going to fight the United States militarily over the future of Greenland.

Daniel Immerwahr: I will say that it is rhetorically distinct what the Trump administration has done in Venezuela, but it is not a new thing. In the last couple of decades, there are other instances where the United States has sought to hunt down a leader or invaded a country, various coup attempts, all that kind of thing. What is really new from the perspective of the last couple of decades is for a presidential administration to say, "We would like to claim a colony. We would like to annex new lands to the United States. We understand that the people who live there, people who control it, don't want that, but we want it."

I think that's not just a naked rhetoric. I think, actually, George W. Bush didn't think in those ways. Barack Obama didn't think in those ways. Nixon didn't think in those ways. The United States fought a war in Vietnam. As far as I can tell, there was no talk about annexing Vietnam. In the Iraq War, there was a lot of hemming and hawing about how the occupation should work, but the Bush administration wanted to get out of Iraq, didn't want to stay in Iraq forever. This is a different form of power. This is something that had been off the menu for a while and is now back on.

David Remnick: What's the history to all this in Greenland?

Daniel Immerwahr: Greenland had long been proximate to North America. There had been moments from the 19th century and then right after World War II when various US statesmen were eyeing Greenland. It got much more important in the age of aviation when it seemed less to be an out-of-the-way iceberg and seemed to be right on the route in any air war with Russia.

For the most part, US presidents have been able to feel comfortable with their lack of ownership of Greenland because they have something else. They have a massive military base, formerly an air base, now a space force base in Greenland, that has allowed them to do whatever they want with their planes. They've basically have had the run of the space for their purposes. It was actually very bizarre when, in his first term, Trump started talking about Greenland. He's been talking about it for years.

David Remnick: It almost seemed like a joke when you first heard it.

Daniel Immerwahr: It did. It seemed like a joke. It was sort of, is he just testing? Is he just trying to say transgressive things? It also seemed frustrating because you think, "Trump, what do you want? You want to land some planes in Greenland? Fine. The United States has been doing that for a long time. You want to buy minerals from Greenland? You can do that. It's open for business. What do you need to actually colonize this space?"

David Remnick: No, you thought it was a trolling situation.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, yes, yes, yes, that's right.

David Remnick: After Venezuela, how can you possibly think that's a trolling situation? It seems to me, though, the cost of what's going on, there are many costs to it. Here's one. If I'm China, I look at what's going on and I say, "Oh, okay, my sphere of influence is obvious. 90 miles off my coast, I have Taiwan."

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

David Remnick: If I'm Russia, "Well, I've already exercised my 'right' to invade Ukraine for historical reasons. Now, you're going to tell me to end the war before I want to? Why should I do that?"

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right.

David Remnick: On and on and on. At the same time, when it comes to Greenland, the desire to take Greenland, which Trump is threatening to do, which Stephen Miller is threatening to do, although Marco Rubio says, "Well, no, maybe we'll buy it," is that you crack up NATO, that you're, in essence, invading a NATO territory.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, yes, something that Trump seems very willing to do. I'm sure that he's surrounded by people. He has been, for years, been surrounded by people who tell him that there's a cost to breaking up NATO. Trump has very little patience for NATO.

David Remnick: What tradition does that come out of?

Daniel Immerwahr: We sometimes call that isolationism. I don't think that was ever a good word for it then. It was a pejorative word by supporters of liberal international order for their opponents. Sometimes you'll see people still call Trump that. You see why it's inaccurate, because Trump is clearly not an isolationist. He really likes bombing other countries.

David Remnick: The United States has done what it's done in Venezuela and is now threatening to do it in Greenland. What tensions will that produce about oil supply or anything else with Russia and China?

Daniel Immerwahr: That's a great question. On the one hand, you might think any move by the United States, especially where China and Russia have interest, is an incursion against them, right? The United States gets the oil. China doesn't get the oil. The United States gets the rare minerals. China doesn't get the rare minerals. On the other hand, every time this happens, it's a little more possible for China and Russia to lock down mineral and oil supplies in other places wherever they want them. If we are going to tilt from a world where goods are sourced on the market and the market is kept open, and the piece is kept by an international system, to a world of power blocks, that might not be a bad thing for Russia and China, even if they lose a little in particular countries.

[music]

David Remnick: I'm speaking with Daniel Immerwahr, a contributing writer for The New Yorker. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour, and we'll continue in just a moment.

[music]

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. We're talking today about the United States and the world, the seizure of Nicolas Maduro from Venezuela, threats against nations from Cuba to Denmark, and the way that Donald Trump uses history to justify his view of the world order. My guest today is the historian, Daniel Immerwahr, who writes in The New Yorker about what the Venezuela operation tells us about Trumpism. Immerwahr is the author of the book, How to Hide an Empire, a bestselling account of the US and its overseas possessions.

[music]

David Remnick: Now, I think we need a history lesson. We need to be reminded of the specifics of what were the basic tenets of the Monroe Doctrine, which Trump keeps invoking after seizing Maduro and invading Venezuela.

Daniel Immerwahr: Well, we're now calling it the Donroe Doctrine.

David Remnick: The Donroe Doctrine. [chuckles]

Daniel Immerwahr: That is what he's seeking.

David Remnick: Which is, by the way, Trump has some talent for nicknames and things like this. This is a bad one.

Daniel Immerwahr: Well, I actually love it because the Monroe Doctrine, as he is interpreting it-- We can get to the various incarnations of it, but the version of it that he likes is an imperial version. Then he's actually colonized the name itself, so it's just so on brand.

David Remnick: He's landed a plane on that.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, exactly right. Yes. The Monroe Doctrine, we talk about it as if it was some great and binding thing. The Monroe Doctrine was a series of non-sequential paragraphs that Monroe delivered in his annual message in 1823. That was non-binding. It didn't have any enforcement mechanism, and it wasn't particularly different from the kinds of things that US statesmen had been saying for a long time.

The idea of it was to try to urge European powers not to invade in Spanish America, which might be a kind of security threat to the United States by declaring separate spheres. It wasn't to say that Europe should have no presence in the Western Hemisphere because Europe had colonies in the Western Hemisphere. Those were allowed by the Monroe Doctrine. It was just to say, "No further European expansion in the Western Hemisphere, please, and also will lay off Europe."

David Remnick: Well, in the press conference after they seized Maduro, Trump said this, "American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again." This language that he used, referring to the Western Hemisphere multiple times, what does that say to you?

Daniel Immerwahr: I think it's yet another example of him reaching back to older traditions in US foreign policymaking. It is interesting. A, the naked force that is being appealed to. B, it's also interesting that his thought is hemispheric, right? He's not saying our place in the world will never be challenged again. He's saying our place in the Western Hemisphere will never be challenged again. In some ways, it's a more modest understanding of US domain than other presidents have had.

David Remnick: How much of this is systematic, and how much of this is chaotic?

Daniel Immerwahr: I think the way I see it is that right after 1945, the United States was just producing most of the world's goods. It had a majority of the world's oil and a majority of the world's gold. It was just in such a staggering position of power that building a world system where it was the center made sense, at least to people in Washington. That's why the UN is located in New York, the headquarters is. I think we've just seen a gradual erosion of the basis for US power. It is not surprising that that is expressing itself in a kind of temper tantrum from a US leader who just really no longer thinks that the thing holds together.

David Remnick: What's your political sense of who's actually for this?

Daniel Immerwahr: That's what's so interesting, is that there are a lot of things that Trump threatens to do or has done where I think, "Wow, this would really be a departure and an alarming one," and yet the MAGA base is for it. Greenland, particularly, you think, "Who in MAGA wanted this? Who was talking about this? Who in the Republican establishment wanted this?" You can maybe say that there's been some Silicon Valley bros who have this vision of Greenland as the laboratory for space exploration, but I just don't see the constituency for a lot of these things other than the machismo that Trump offers, right? We are just going to--

David Remnick: That's it. That's it. In old imperial days, there was a sense that the leadership of the country, there came a time when they wanted to hide our imperial presence in the world. Now, it seems it's almost advertisements for myself that Trump wants to advertise and amplify imperial ambitions and aggression.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes. The moment of most stark imperialism in US history is around the end of the 19th century, which is when the United States went on a colonization spree. The usual take on that is, this is the generation that was too young to fight the Civil War. They feel a sense of heroism. They want to feel a sense of heroism that their fathers had that they haven't got.

So much of the imperial expansion of the United States was not just rendered in the cool calculations of, "Well, this will help our balance sheets and our business might expand." It was, "This will psychologically redeem us. This will feel good. This will be an arena for masculinity." Trump is offering that. That part of it seems to sell. A lot of MAGA is about gender roles, particularly about masculinity and about men who've been constrained and oppressed and become effeminate, finally get to be men again.

David Remnick: Well, we'll see what Joe Rogan has to say when the time comes, but I don't know that that's a-- it's getting unanimous MAGA applause. You look at Marjorie Taylor Greene, who obviously has become a dissident within that movement. She's not alone. There's a lot of people in the movement who are very, very loyal to Trump, who find this a betrayal of America First and a sense that there are plenty of problems at home that need attending to, and we don't need to be invading Venezuela, threatening Colombia, threatening Greenland, and on and on.

Daniel Immerwahr: There's this slippery slope between a threat, an airstrike, abducting the president, and then, as Trump has pondered, running the country. I think the further you slide down that slippery slope, the less it looks like America First, and the more it looks like nation-building. All the things that Trump ran against. You can see this as very quickly becoming a sharp betrayal of Trump's base.

David Remnick: In the piece about McKinley and tariffs that you wrote for The New Yorker, you wrote, "Tariffs did lead to colonization. The depression of the 1890s, exacerbated by McKinley's tariffs, stirred American support for taking colonies in order to right the economy." Do you think something similar in cause and effect is going on now?

Daniel Immerwahr: I'm not sure that I see Trump connecting those dots, but there is clearly a political crisis that has been caused in part by Trump's tariffs. He's a self-inflicted economic crisis, or at least an amplification of the inflation problem that we were dealing with before. This seems like a way to politically square the circle. I'm not sure that it will economically square the circle. I'm not sure it will resolve the issue. Trump has painted himself into a corner politically, and I think he regards this as a way out. This is the first good news day he's had, at least vis-a-vis parts of his base, in a long time.

David Remnick: You think that was a good news day for him?

Daniel Immerwahr: He's clearly taken great pleasure in it. It's a show of strength, which has been an important part of who he is. You're right that not everyone is on board with this. I think for a certain kind of Trump supporter, this looks good. This is the kind of thing that the United States hasn't done in a while.

David Remnick: Well, this is exactly my next question. The invasion of Venezuela was 36 years after the invasion of Panama. How would you compare these two operations?

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, so a huge difference is that with the Panama invasion, that was clearly a rogue yes-man. Noriega was someone who had worked with the United States. It came out during Iran-Contra that he'd been--

David Remnick: With the CIA.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, with the CIA. He'd been on the CIA payroll, which was very awkward for George H.W. Bush, who'd been in charge of the CIA. In fact, one of the reasons that the Reagan administration held off on opposing Noriega was that it would just be too embarrassing for Bush. He's a kind of classic case of someone who'd been really useful to the United States and then becomes less useful and then gets taken out by the United States.

That's one difference. A big question, a big possible difference is where this ends. Right now, it looks from the US perspective as if, potentially, it could just be a single operation. An unpopular leader was taken into custody, will be tried. I don't want to suggest that there were no more ongoing consequences for Panama for that. We can talk about what that looked like in Panama after. From the US perspective, it was more like the Gulf War than the Iraq War. I don't know if that's going to be true here.

David Remnick: Because what could happen in Venezuela? Prediction is lousy journalism and even worse history, but give it a shot.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes. Okay, so first of all, it is always the fantasy of post-'90s US presidents that they can solve all their problems with airstrikes and with surgical strikes. They can just go and do exactly what they want to precisely the people they want, and then they'll be out. That has not always happened. That was George W. Bush's fantasy with Iraq and Afghanistan. It famously was dashed against the rocks of reality. I think a huge structural problem is that, who's next? What's next?

If the administration of Venezuela is compliant enough with Trump that Trump sees no need to do, as he threatened, a second wave of attacks, then that's a massive legitimacy problem within Venezuela. Often, these people who are potentially supported, potentially opposed by the United States, these leaders are in a really unstable position because if they comply with the United States, they have a huge problem with their base. If they pander to their base, then they might have a coup attempt. Venezuela was already in that position, but I think it is much more so now. The odds that things spill really out of control, I think, have gone way up.

David Remnick: Daniel, from your political point of view, which is informed by, obviously, years and years of studying history, is foreign intervention, American intervention, ever justified?

Daniel Immerwahr: I think there are two questions. One is, is it justified? Meaning, is the target a suitable target? Is this someone who the world would be better off if this person weren't in power? I think the answer is sure, but then there's another question.

David Remnick: What's an example of that?

Daniel Immerwahr: Okay, so I think with Maduro, stolen election, wildly unpopular, I think there's a great argument to be made that Venezuela, in the abstract, is better off without him being in power. I think a lot of Venezuelans feel that way. You can make a longer list, and it would include Saddam Hussein, et cetera. The problem is you cannot just think of this as a deus ex machina operation, where one person is taken out of power.

You actually have to think about what happens when the United States intervenes. Then any number of downstream effects ensue. There, it's a lot harder to make the case that US intervention has been good for the country. By and large, and we have studies of this, the effect of the United States intervening in a country makes it more likely to have a coup, to go to war with the United States, or to clash with the United States, or to start having massacres within its borders. It tends not to be good for the countries who get intervened in.

One thing to keep in mind, because we keep thinking, these journalists keep going for the Panama example, is to think about what happens in Panama after Noriega, who was wildly unpopular, is taken into custody. There is an ongoing political crisis in Panama because the new government, the new head of state, is sworn in on a US military base and then has a huge legitimacy crisis. The story of post-Noriega/Panama is not a happy story. It's a story of drugs going up, crime going up, and just repeated sovereignty clashes involving the extension of US power into Panama.

David Remnick: In my lifetime, every time something like this has happened, two objections are raised among others. One is international law. These things are called a violation of international law. Then there's the hue and cry about congressional approval. What is international law in this case, and what power, if any, does it have?

Daniel Immerwahr: Okay, so it doesn't seem to have a lot of binding force. The idea is that as the steward of the system, the United States has had some obligation to make some case that it is acting in consort with international law. It has done that in the past. That's been a way of reassuring everyone that, "Okay. Yes, we're invading Iraq and, yes, it doesn't look great, but we have a case to make why this is okay and why this doesn't mean that China can take Taiwan."

In some ways, we're all still good. We're all still invested in, generally, countries shouldn't be invading each other. When you see something like what Trump is doing, which is openly flouting international law, complete lack of interest in it, those expectations, norms, taboos, which are important in international affairs, start to break down. Then other countries think, "Well, is international law going to be binding on me? Is it going to be enforced on me? Could I maybe get away with just breaking it?"

David Remnick: If I am Xi Jinping or his successors or Vladimir Putin, who's not going to be succeeded, by the way, by liberal internationalists, they are pleased about this. Yes, they may have interests in Venezuela, but they have an even greater interest in their own sphere of influence and their ability to control it however they like.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, yes, yes. Not just feel that, but the more that they act on that feeling, the more they erode the norm in every other way, because you wanted to think that it's not okay to invade another country. If you tried to invade another country, the weight of the whole world would come crashing down on you, probably led by the United States. It would just be too dangerous to do that. It doesn't seem too dangerous to do that anymore. It seems dangerous, but not too dangerous to do that.

David Remnick: Daniel Immerwahr, thank you so much.

Daniel Immerwahr: Thanks so much, David.

[music]

David Remnick: Daniel Immerwahr is a professor in the history department at Northwestern University. You can read him on Venezuela at newyorker.com, along with reporting from staff writer Jon Lee Anderson, Dexter Filkins, and many others. You can also subscribe to The New Yorker at newyorker.com. Last week, the White House announced it was withdrawing the US from dozens of international organizations, and that includes UN groups as well, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[music]

Copyright © 2026 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.