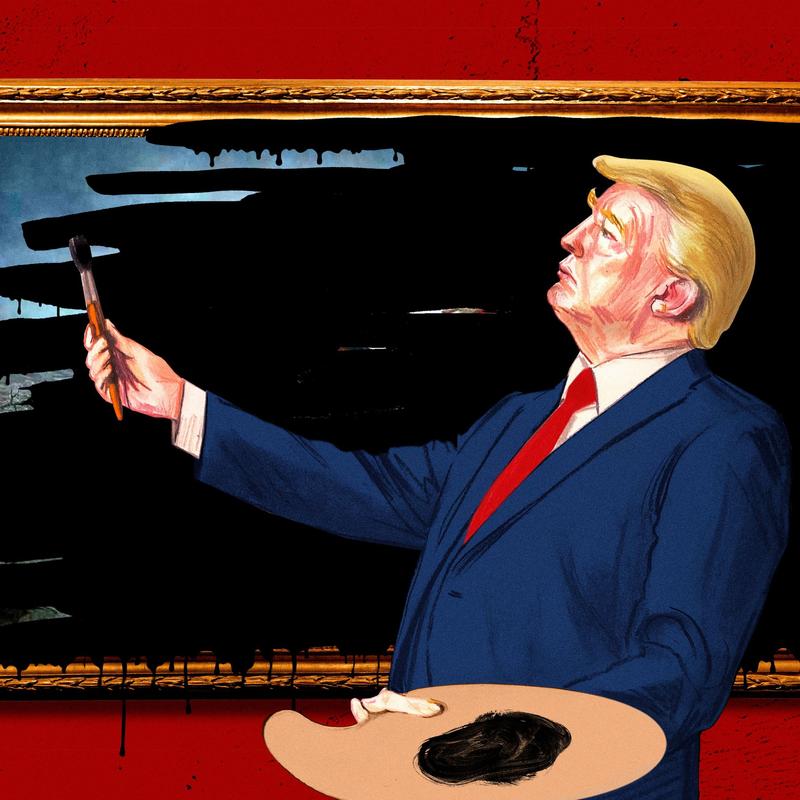

Donald Trump’s War on Culture Is Not a Sideshow

David Remnick: Usually, when we talk about the culture wars, we mean issues of sexuality, race, religion, and gender. As recent months have made plain, when Donald Trump thinks about the culture wars, he also very distinctly means the arts. Trump has very definite tastes in what he likes to see and what repels him, too. At the start of his second presidency, Trump fired the board of the Kennedy Center, and now the Republicans would like to rename the building for him. His administration pressured the director of the National Portrait Gallery to resign, and they fired the National Archivist and the Librarian of Congress. His attorneys are reviewing the entire Smithsonian Institution, looking for what the President calls improper ideology. Now, one reading of all this is that culture makes an easy target. It seems easy elite, and that all this is a deflection from the Epstein Noise and the Ukraine war and the tariffs and so much else. My colleague Adam Gopnik believes this is a serious misreading.

Adam writes widely for The New Yorker about culture and history and much else, and we spoke last week. What is the nature of this culture war in the second presidency? Not just the details, but what is it aimed at doing? What is it? What is it not?

Adam Gopnik: I can't speak for Trump's intentions, and often I think we make a mistake in overreading his intentionality and imagining that there's a scheme when there's simply a set of stimulus and responses that go on. I think that there's this enormous sense, certainly around the people who he surrounds himself with, that they have been wounded by American culture in some profound way.

David Remnick: That they've been lectured to by left-leaning university presidents and teachers and museum curators and mass media and mass media and-

Adam Gopnik: Yes. Exactly.

David Remnick: Adam Gopnik, or whomever.

Adam Gopnik: He's particularly annoying because he stands up there yelling. You can make a rational case that there is always something to be said for the populist restimulation of American culture. It's part of the Jacksonian tradition. Of course, pluralism is the key principle of a democratic culture. We have no trouble in our lives appreciating the art of the Las Vegas strip or the late Elvis and at the same time reading Tolstoy. Those are not activities that cancel each other.

David Remnick: What he's attacking, and when I say he, I mean Trump--

Adam Gopnik: [crosstalk] Trumpism.

David Remnick: What they're looking at, for example, is humanities departments in the main universities and in a saying that's completely left. It's reminiscent of William F. Buckley at Yale many, many years ago.

Adam Gopnik: Many, many years ago, suggesting that it's a persistent theme, not some new discovery.

David Remnick: With different themes. Buckley was concerned with religion, Catholicism being pushed out, and so on. Here, the concerns have to do with "Wokeism." Their concerns have to do with the study of history, which is very familiar to me, coming from having lived in falling Soviet Union. The importance of that. To what degree is there a point there? To what degree is this a full blown culture war that scares the hell out of you?

Adam Gopnik: Much more the second than the first and at the same time, because that's the obligation of the liberal imagination. Of course, there's a point there. I've written at length over the years against progressive pieties as they take control of cultural institutions--

David Remnick: For example.

Adam Gopnik: Well, the whole idea of cultural appropriation I've always found absurd and have said that culture is, in its nature, art. Forget the word culture, which is an ugly word. Art and civilization are in their nature hybrid activities. The impressionists pulled from the Japanese printmakers, and then the Japanese printmakers learn from the impressionists. The story of the popular music You and I. A door is a story of constant hybridization. Muddy Waters get sent out to the port of Liverpool and it comes back five years later as the Beatles and the Stones.

That's healthy, essential. That's what civilization is, the constant hybridization of kinds. The rhetoric of cultural appropriation is something inherently sinister, I think is crazy. To the degree that's typical of one face of a particular kind of cultural, you should forgive the expression, hegemony of a particular kind of cultural conformity. Of course, there is something in that but, and this is the biggest but of our time, there is all the difference in the world. There's a difference of night and day between the unfortunate tendency of intellectuals and artists to trope towards conformity and a declared state policy on the arts.

One is the normal working out of a civilization, there other is-

David Remnick: Of argument.

Adam Gopnik: -of argument and persuasion and change and fashion and vogues and all of those things that come and go. The other is the model of the authoritarian control of art. That is the state dictates an ideological line.

David Remnick: We're now seven months into a second term, Adam. Sketch out how you see what Trump is doing, his strategy, the details of it, and what it all might resemble from past experience abroad.

Adam Gopnik: The key thing is that a democracy rests on lots of pedestals. The two key ones, I think, are obviously free and fair elections and the rule of law, somehow defined. The other, just as important, is social coexistence. It's having a pluralist culture. It's people understanding that our tastes, our creed, our faith cannot trump, so to speak, all the others. Having pluralist cultural institutions is not the windshield decor on a democracy. It's the foundation of a democracy.

We should be able to say, and in the past, we have been able to say-- Tony Kushner's politics are well to the left of center, and David Mamet's politics are way to the right of center. At least they are now. They are both, in an arguable sense, great playwrights who have changed the nature of American theater. It should not be difficult for us to have a national stage in which both Kushner and Mamet make an appearance.

David Remnick: Are we heading toward a culture war in which the President of the United States says that Angels in America can't be at the Kennedy Center?

Adam Gopnik: Yes, Angels in America, Hamilton, the most conservative work of musical theater ever written. That those things are inadmissible because they are woke or because they are lefty. Now, I understand the counterargument, David. I do. To say, well, yes, but then where are the Ivy League institutions that are teaching Mark Halperin and David Mamet and even Tennessee Williams? That's not an empty argument. Again, there's all the difference in the world between the processes of persuasion and argument that produce cultural debate-

David Remnick: [crosstalk] Policy.

Adam Gopnik: -and policy, and the imposition of a cultural line which depends, as it did, and I will use the instances, as it did in the Soviet Union under Stalin, as it did in Nazi Germany, as it does in every authoritarian country. It depends on allegiance to the boss.

David Remnick: Well, let's take this Soviet experience as an example. Stalin was somebody interested in culture. In fact, that was the price of the ticket to be a leader of the Communist Party. You had to at least feign interest in Russian literature and music. You had the spectacle of Stalin going to one of the great concert halls in Moscow and witnessing a Shostakovich performance and then coming back and essentially dictating a review, denouncing Shostakovich, and ruining the rest of his life and setting down the parameters of Soviet music.

There were similar examples in Pravda and Izvestia about Russian literature. You knew who was out and who was in. There was a writer's union that you had to belong to in order to get published. Are we heading in that direction?

Adam Gopnik: Look, I pray and believe that we are not, but that is certainly the direction in which one inevitably heads when the political boss takes over key cultural institutions and dictates who's acceptable and who is not. It's funny you mentioned Stalin. I was just watching that great movie, The Death of Stalin. That's what it's all about. He's once a recording, if you remember, of the Mozart piano concerto, and everybody is in desperate straits to reproduce a non-existent recording.

Speaker: I have wonderful news. Comrade Stalin loved tonight's concerto and would like a recording of it right away, which we don't have for reasons that are myriad and complex. Meanwhile, concerto we just played will be played again, and this time we will record it and we will applaud it.

[applause]

Adam Gopnik: That is the nature of an authoritarian society.

David Remnick: I don't see Trump as a cultural consumer as being particularly voracious of anything other than really television and television news.

Adam Gopnik: He loves Les Misérables, Les Mis, and I tried to articulate--

David Remnick: That's ironic, isn't it?

Adam Gopnik: Ironic? I don't think it's quite the adequate word for what that is.

David Remnick: Explain why.

Adam Gopnik: Les Mis is Victor Hugo's great novel of protest against social injustice. It is the ultimate expression of the social justice warrior armed with a pen. I think more significantly, it's a protest against authoritarianism. Very specifically, it's about Louis Napoleon, Napoleon's nephew, who ruled France for almost 20 years and whom Hugo was implacably against in ways that are eerily parallel to Trumpism. Now, we can look back on it and say it was, as autocracies go, a relatively, put this word in heavy quotes, "benign one."

David Remnick: How do you make sense of the specific moves that Trump has made so far, where the head of the National Portrait Gallery is forced out, the board and the leadership of the Kennedy Center is overturned?

Adam Gopnik: These are daily insults to the very idea of a pluralist civilization. The people were let go from the Kennedy Center board because they were not primarily loyal to Trump. Everything is redefined on an axis in which there is only loyalty.

David Remnick: I'm speaking with The New Yorker's Adam Gopnik. We'll continue in just a moment. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour.

[pause 00:11:10]

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick, and I've been speaking today with Adam Gopnik. Adam has written for many years at The New Yorker on questions of culture in history and democracy. He's thought very hard about what makes a democracy live and breathe, and also what can bring it to an end. We've been speaking about Donald Trump's campaign to seize control of American culture on a number of levels: museums, universities, performing arts centers, any institution that receives government support.

Trump wants to root out what he calls improper ideology, a phrase that would seem to threaten the First Amendment itself. I'll continue my conversation now with Adam Gopnik. So far, the moves, for the most part, have been aimed at institutions that are within the government's easy reach. How do you think it will affect institutions that are a bit more distant, whether it's a movie studio?

Adam Gopnik: David, I will say, I said after the election that the first thing you would see would be mass pardons. Everybody was saying at the time, not everyone, but many people were saying, "Oh, he'll pardon the lesser offenders, but he won't try to let the really violent people who beat up cops go."

David Remnick: They all came out.

Adam Gopnik: They all came out, including people who had been violent on his behalf against cops. Then I said Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert would be next. Six months on, you would see them disappear. Now, we have elaborate rationales for--

David Remnick: The elaborate rationale for Stephen Colbert is that the show is losing $50 million a year.

Adam Gopnik: Right. That may well be true. Do you suspect, David, that if Stephen Colbert were known to be a Trump sycophant, that that would have affected CBS's--

David Remnick: I'm not saying I accept this rationale. Apparently, when they were totting up these numbers, they didn't include the money that comes from cable affiliates.

Adam Gopnik: That's a significant, but the point is that you can see how effectively that happens. It is typical of every authoritarian society. Talk to your Hungarian friends about how it happens. Each time we find a rationale for it or a rationale is offered, and it's much easier for us to swallow the rationale than to face the reality. Because by swallowing the rationale, we can say, "Well, I enjoyed Stephen Colbert, but really, when was the last time you watched Stephen Colbert's show in its time slot? It's not the way we experience Comedy.

David Remnick: It's through YouTube the next morning.

Adam Gopnik: YouTube the next morning.

David Remnick: Some of this is thematic. You look at the effort against museums in Washington, and one of the themes that constantly comes up, whether it's the African American museum or elsewhere, is about slavery. Trump was given a tour of the African American History Museum, and he's complained that museums focused too much on, "how bad slavery was" and want us to focus on, I suppose, a cheerier view of the past.

Adam Gopnik: Yes, listen--

David Remnick: This has the ring of familiarity.

Adam Gopnik: Yes. Obviously, it has been the case since 1865 that there is a very powerful current in American life that wants to rehabilitate the Confederacy and insist that slavery was not the proximate cause of the Civil War, that--

David Remnick: Why would Donald Trump, who was born and raised in Queens, care about this? Is that an attention to his constituency?

Adam Gopnik: David, I hardly need remind you that Donald Trump came to prominence as a political figure by saying that Barack Obama was not an American.

Donald Trump: If he weren't lying, why wouldn't he just solve it? I wish he would, because if he doesn't, it's one of the greatest scams in the history of politics and in the history, period. You are not allowed to be a president if you're not born in this country. He may not have been born in this country. I'll tell you what, three weeks ago I thought he was born in this country. Right now, I have some real doubts.

Adam Gopnik: That's what he rose on. It's so typical of what happens. We've written that out now, and we say, "Oh, well, Trump rose because he spoke to dispossessed middle Westerners. He wasn't talking about economic anxiety; he was talking about how Barack Obama, a Black man, was not an American. Why are we surprised when that reappears in the context of the debate on the Smithsonian? Once again, and this is the hard part, where your intellectual integrity goes to war with your five-alarm sense of the threat to democracy.

Of course, it's possible to have arguments, and we could debate the famous 1619 Project about exactly how essential racism and slavery are to the foundation of America. A perfectly reasonable case can be made that, though they were one essential stream, the stream running in the opposite direction, the abolitionist stream and the Quaker stream, and all of those things, that's why we had a civil war. That's why they called it a civil war, because there was a powerful stream running in the other direction. That's an argument about history that is worth having.

David Remnick: The 1776 project, which was constructed to--

Adam Gopnik: Counter the 1619.

David Remnick: The basis that was what in your view?

Adam Gopnik: It was straightforward propaganda. Straightforward propaganda. It's no authentic desire to explore the complicated and many-sided issues in a national history, but simply wants to lay over by now very familiar America first, Charles Lindbergh, Joseph McCarthy, fiction about American history. We don't need the fiction. That's one of the things that's so painful about it. We're grown-up people, we can count to two. We can say we're immensely patriotic Americans, hugely proud of the inheritance of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

At the same time, we recognize how much exploitation, cruelty, and, particularly in the history of slavery, outright evil there was in the founding as well. You have to be emotionally stunted not to be able to say both things are true at once, and we can recognize both truths.

David Remnick: Let's talk about the museum world, which you know so well. Trump has claimed that museums are, "the last remaining segment of woke."

[laughter]

You laugh, I laugh, but what is he talking about there? What's he fastening onto? What granules of reality is he focusing on?

Adam Gopnik: I very much doubt that Trump has been through the last six exhibitions at the Metropolitan and MoMA and making notes on the tendentious nature of the--

David Remnick: Let's call it his administration.

Adam Gopnik: Right. It's indisputable that there has been a move, compensatory in its original motives, to rewrite the history of art as it's told in our museums, to make it, if I can use the word, more inclusive, to include more women, more people of color, who, and it's perfectly fair to say, have largely been left out of that story. That is a process that's perpetually ongoing, in which intellectuals and curators and academics and critics are engaged in perpetual conflict and perpetual argument. Over time, those arguments, they don't tend to get resolved, but they tend to produce new work, interesting new angles, interesting new vantages.

We wouldn't want now to think about the history of Abstract Expressionism without including Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler and Lee Krasner, and artists who were, it's absolutely true, were left out of that story as it was first being told. Does that negate the value of Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock? No, it expands it. It makes us understand that moment of artistic ferment in a much broader way.

David Remnick: [crosstalk] No one suggested the culture warriors on the right are rushing to the defense of Mark Rothko.

Adam Gopnik: No. David, part of it is deeply, to my mind, and I use this word cautiously, is deeply tragic because one of the triumphs of American civilization with all of its deficits, and God knows I've been writing about them, we have had an extraordinary moment of pluralistic cultural revolution, where things that had once seemed terribly threatening, damaging, like modern art, have come to be part of the common experience. To see it being ripped apart is not trivial.

It's a profound failure and one we have to protect while remaining aware, if I may say remaining awake, to the inevitable limitations of progressive pieties in power.

David Remnick: One of the things that obtains an authoritarian and totalitarian regimes is not just the official moves against publishing houses, museums, academia, and so on, but what it produces in artists, intellectuals, and so on. The phenomenon of self-censorship. The fear, then, is how you reach people. In other words, your powers of persuasion as a writer. If you keep banging on every single day about the latest outrages, and they come every single day in multiplicity--

Adam Gopnik: On the hour. Yes.

David Remnick: I'm afraid so. What language do you use? How do you behave as a writer, as a communicator, as a journalist, as an essayist, so that you have some effect beyond preaching to the choir who is prepared to hear this and accept that language? How do you convince anybody of anything and not be defeated?

Adam Gopnik: It's a profound question. On the first part, whenever someone talks about you're preaching to the choir, I don't feel that that's true. What you're doing is you're teaching the choir how to sing in tune. In other words, you're saying, here's the language, the kind of language we should use, here's the kinds of things we should care about. You can use the language of rationality. You can use the language of liberal humanism, if I may call it that, to remind people of what the right tone is to use, as opposed to the hysterical or ideologically fixated tones that we can so easily fly into.

David Remnick: How do you respond to readers who say, "Adam, it's already bad enough you're hysterical. Nobody's bursting into the studio to arrest you, to censor you. Take it easy, Adam."

Adam Gopnik: I'd say, yes, we should take it easy in the sense that we should turn to a language of wit and humanity. In everything I write about--

David Remnick: What good does wit do? Another well-posed jab at the at the Trumpies--

Adam Gopnik: You know who one of my greatest heroes is, David? Maybe my single greatest hero is Albert Camus. Why? Because when he was writing--

David Remnick: A hilarious writer. A man of great sardonic irony. A French version of hilarious. Because when he was writing for Combat, the French resistance journal, basically it was read by nobody. Because it was a subterranean resistance journal. Yet he wrote these beautifully crafted, many-veined, multifaceted essays that were not, as the work of the Communist Party in France was in that way, narrowly, brutally ideological. They were trying to make sense out of a time that made no sense.

That's our task and that's our job. Our job, I think, is not to persuade in the first instance, because who knows how persuasion happens? Victor Hugo wasn't trying to persuade. He was trying to remind. He was trying to alert. He was trying to--

David Remnick: To get the reader to see.

Adam Gopnik: To see. To get the reader to see and to offer an alternative vision of human possibilities than the one that was being dictated by the Second Empire and by Louis Napoleon. He was saying that's why he calls it Les Misérables. He said, all of these people who we don't know well-

David Remnick: Are immiserated.

Adam Gopnik: -are immiserated. They're engaged in the same daily struggle for a meaningful life that everyone is. It's why even Donald Trump loves Les Mis, because when they sing Bring Him Home, it has real weight because it comes from Hugo's ability to absorb the entirety of his own society.

David Remnick: Trump's attention span is a very important element of our politics and our time. Much depends on his ability or inability, or desire or non-desire to follow through on the impulse of the day. How far do you think this culture war will go, as opposed to all the other fronts that he's fighting on?

Adam Gopnik: The truth is that I recall, as someone raised in Canada, when Trump was all afire about annexing Canada. We haven't heard very much about that in the last while. Mark Carney seemed said--

David Remnick: [crosstalk] The only thing it seemed to do was to mobilize Canadian politics.

Adam Gopnik: Yes, and change the result of the election from a conservative to a liberal. He seems to have put that aside for the moment. That may be the, if you like, the Louis Napoleon side of Trump. It goes back and forth in that way. I don't think we can underestimate it. There are troops in the streets of Los Angeles and Washington, DC, Chicago shortly. This is not--

David Remnick: New York, I assume, is coming.

Adam Gopnik: Yes. The one thing I'll say about Trump's ability to be constantly omnipresent, and this is genuinely, I think, an interesting and significant generational divide. My daughter Olivia, just graduated from college, is politically active, organizing conferences. The side of Trump that I find degrading, she finds not normal, but certainly understandable. That is the round-the-clock drumming on social media and so on. Her response, and the response of her generation, is we have to do the same.

It's Mamdani doing the treasure hunt. The scavenger hunt. It's the understanding that that's the cockpit, that's the coliseum in which this war is fought, and that in some--

David Remnick: Social media--

Adam Gopnik: Social media, TikTok, vertical videos, the whole idea that you have to be plugged in in a different way. John Updike, to my mind, the greatest single writer who ever graced these pages and these halls, once wrote, memorably said, "At any moment an old world is passing and a new world is coming into being. We have sharper eyes for the fall than the rise, because the old world is the one we know." I've always thought that the wisdom of that is something that all of us should keep perpetually in mind and not in--

David Remnick: You're suggesting we'll survive this and worse?

Adam Gopnik: I hope and believe we will survive this and worse. The daily dose of even the minimal courage it takes to write something is something I'm sure you feel this, that you have to draw on again, who wants it really, but it's--

David Remnick: No. Sometimes I feel, Adam, is I don't want to write about this at all after a while. I want to be able to go to a museum and think about art or read a book and think about the novel, and not be completely consumed all the time. With politics, there's no relief from it.

Adam Gopnik: It feels more oppressive. I feel blessed because I still write with joy about the Frick museum opening or arguments about the history of the Renaissance, and so on. They all turn around, though the same fundamental underlying issue, and that is the persistence of a humane civilization in an inhumane time.

David Remnick: How much of this matters? What we've been talking about in the sense that we now have statistics that tell us that reading has diminished, going to the communal movie theater has diminished, that something has happened to our attention spans, and the way we're reading or not, and what we're looking at or not. How much does this culture war matter?

Adam Gopnik: I'm something of an optimist, or at least a bit of a neutralist about that. To use a terrible prefix to a sentence, you and I are old enough to remember when people said about television, network television.

David Remnick: There was a famous book, Four Arguments for the Abolition of Television. Yes.

Adam Gopnik: I'm a bit of a steady state thinker about how those things proceed. I think that what you put your finger on, though, is that the problem is that politics should be arguments about policy, if you like, how high should interest rates be? What's the best way of providing housing? Then deeper issues. I believe in gun control-

David Remnick: Gun control, sure.

Adam Gopnik: -but people believe that guns are a form of autonomy. Those are all arguments we can have. Eliminating the possibility, denigrating the necessity of a pluralist civilization, is a plague that I think is almost impossible to recover from. It's our job not to persuade because we have limited power to do that, but to assert the value of pluralism over and over every week, if you like, and certainly always in our work.

David Remnick: The last time you were here, you made some dire predictions about what would happen, and if anything, they've been eclipsed by worse. There's in excess of three years left in this administration if things go their normal way. What do you predict in terms of culture war and the eclipsing of democratic norms further?

Adam Gopnik: It could very well continue to go worse and worse. The 20th century was a horrible century, but it taught one unmistakable lesson, which was that you had to be as hard on the totalitarian temptations of the left as you did on the authoritarian appetites of the right. It was perilously easy then, as it is perilously easy now, to say, "Well, but they're on my side." You see this happening on the right all the time. Otherwise decent people who know what kind of an authoritarian Trump is, who recognize it, who have no sympathy with him as a human being or as an ideological say, "But the other side is so dangerous.

They're so woke. They're so anti Semitic." You can find 100 reasons, and then you make a deal with the devil. That's why we call it Vichy. That was the key thing, property of the Vichy regime in France in the Second World War. It was that all of those right-wing intellectuals hated the Nazis, hated the Germans, but they hated Leon Blum and the Socialists even more. That was a deal they made with the devil that France has regretted ever since. It was a primal wound to French dignity and to French continuity.

We are in the process of inflicting a similarly primal wound on ourselves if we do not remember the lesson that history teaches us, which is you have to be equally discerning and equally determined not to fall prey to that temptation.

David Remnick: Adam Gopnik, thank you.

Adam Gopnik: David, pleasure to talk to you.

David Remnick: Adam Gopnik is a longtime staff writer at the New Yorker, and you can find his work at newyorker.com. By the way, this week we published a special anniversary issue all about the culture industry, an issue in which Jill Lepore considers Trump's directive to the Smithsonian. Many of our reporters examine everything from the fall of pop music criticism to the rise of A24, the hottest movie studio around these days. If you look closely, there is something anomalous about the cover as well. You can read all of it and see all of it at newyorker.com, and you can subscribe to The New Yorker there as well. Newyorker.com.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.