Dark Side of the Earth

( NASA )

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

MARK VANDE HEI: All right. Howdy!

JAD ABUMRAD: Hi.

MARK VANDE HEI: It's Robert and Jad, I think.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yeah.

JAD: Wow, are you actually in space right now?

MARK VANDE HEI: I am. Let me see if I can prove it to you. Here's a demonstration.

JAD: Oh, wow! That's so cool! [laughs]

ROBERT: Okay, we believe you. [laughs]

JAD: This is Radiolab. Jad, Robert.

ROBERT: That guy that we were just talking to is named Mark Vande Hei, and what he did, is he—to show us where he was, he tucked his neck down into his chest and spun.

JAD: Like a space flip.

ROBERT: He did a space flip.

JAD: So we should explain, like, so this is one of the weirder things that has ever happened to us.

MARK VANDE HEI: Are you hearing me okay?

JAD: It's a little louder.

JAD: A couple weeks ago, we actually got to talk to this astronaut, Mark Vande Hei, while he was in the International Space Station. Apparently, each astronaut at the space station can make one request to talk to an Earthling of their choice. And for some reason, he chose us.

MARK VANDE HEI: So how are you all? This is really exciting for me to talk to you. I've really enjoyed your program.

JAD: Like, we actually got initially contacted by NASA. They told us to dial in to Mission Control at a certain time, and we did, and they then connected us to him, 200 miles up. And we could see him on our iPad as he was in space.

MARK VANDE HEI: [laughs]

JAD: And so we spent—I don't know, like, an hour.

ROBERT: An enchanted hour, I'd say.

JAD: Talking to him, asking questions about what is like up there? But mostly looking over his shoulder back at the Earth.

ROBERT: He invited us to this little place that they have on the spaceship called the Cupola.

MARK VANDE HEI: There's one really big window here called the Cupola. Let's see if I can get you a good view.

JAD: It's basically a giant room with giant windows looking right down at the Earth.

MARK VANDE HEI: Straight down. So our best windows are ones that look straight down. So we just passed over the southern edge of Australia.

JAD: At that time, it was night time in Australia.

MARK VANDE HEI: We're over the night side of the Earth right now.

JAD: And you could barely see the Earth. It was just this big pool of black.

ROBERT: No contours. No edges.

MARK VANDE HEI: So I'll check to see how long it'll be before the sun's shining on the Earth below us. I'm gonna open up one of the shutters, and that horizon that you're seeing out there?

JAD: He pointed out the window at this band of light that had just appeared in the dark.

MARK VANDE HEI: That's the sun coming over the horizon. So that's the horizon of the Earth. It's kind of blasted out in this ...

ROBERT: So then all of a sudden, like a few minutes later ...

MARK VANDE HEI: Bam! Everything changes really fast.

JAD: The Earth just lit up.

ROBERT: All the lights went on.

JAD: You know, because they were going 17,000 miles an hour, and when you're going that fast, sunrise is basically instantaneous.

MARK VANDE HEI: Oh, wait. No, there's definite land mass here. I don't know if you can see it out there. See it?

JAD: Yeah.

JAD: As we were talking, we zoomed over Australia, over the Pacific.

MARK VANDE HEI: Yeah, we're definitely over North America. In fact, I can't tell what state, but we're in the mid-Rockies right now in the United States.

JAD: Within just a couple of minutes it felt like the scenery out his window went from Rocky Mountains to somewhere near New York.

MARK VANDE HEI: Due north of New York. Somewhere out there is where you guys are. Yeah, we're gonna hit Europe soon, I'm sure.

JAD: Then we were over the Atlantic.

MARK VANDE HEI: In fact, see that? The sun is breaking up the ocean there? The interplay of the sun and the ocean is really neat. You can see these patterns of white.

JAD: He's pointing out all these sort of shimmering patterns on the ocean and these swirling cloud masses. And as we were sort of screaming across the face of the Earth, you know, we were asking him all these mundane questions like "How do you eat rice in space?" and things like that, well, at a certain point, we asked him, like, when you first got up there, what was most surprising to you? And he started talking about the Earth's atmosphere.

MARK VANDE HEI: I think—so my first impression when I got up here was that it—that thin layer of atmosphere is shockingly thin from up here.

ROBERT: He says that it's funny to him, now that he's been up there for a while, to understand how close we all are to deep space. That the people who live on Earth are all actually under a very skinny, protective wrapper. It's been described as less thick than the skin of an apple around an apple. All of us, just a few miles from the darkness.

MARK VANDE HEI: So it makes this layer of space that we live in seem incredibly thin. The other thing that shocked me was how intensely black the blackness in space is compared to the sun and the Earth, so it makes the Earth seem very, very isolated. It's such an interesting feeling. That's a feeling of almost a little bit protective towards this spot.

JAD: He says when he looks down at the Earth, and he sees just that thin layer that separates us from space and all the blackness around it, he feels protective. We just kind of wanted to share that because it was just this weird thing that happened to us randomly, just a few weeks back.

ROBERT: Well, actually, as cool as that was, it's a—it's an hor d'oeuvres to what another astronaut once told us

JAD: Yes.

ROBERT: Who wasn't a listener.

JAD: Definitely not.

ROBERT: He—I don't think he knew—when we called him, I don't think he had the faintest idea who we were. That was in more of an official, formal ...

JAD: Right, right.

ROBERT: ... sort of thing.

JAD: So for the rest of this podcast, we're actually gonna play you another astronaut story that we ended up taking on stage as part of our In the Dark tour, which was ...

ROBERT: A few years ago.

JAD: 2012, I think. Went to about 20 cities. This particular recording happened in Seattle, I believe.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: And I don't know.

ROBERT: I think you should just push the Go button.

JAD: We should just play it. So here it is.

JAD: So for our final segment, we were thinking through this show, we thought, you know, who would have a really interesting perspective on darkness?

ROBERT: Maybe somebody who works in a rich, dark environment. Astronauts, for example.

JAD: Yeah. So we called up NASA, talked to an astronaut. We connected our little studio in New York to their studio in DC to talk to an astronaut, but he was a little late. And here's the funny thing: when you are on hold with NASA, this is literally what you hear.

[epic classical music]

[laughter]

JAD: This has a blast off feel to it.

ROBERT: Yeah, it does.

JAD: This is amazing.

ROBERT: This, by the way, is literally the case. You dial 1-800-NASA or whatever, and this is, like, go to the moon music.

JAD: Uh oh. Hello? I hear someone breathing. Can you hear me?

DAVE WOLF: It's probably—I'm breathing.

ROBERT: [laughs] That's an interesting way to meet.

JAD: So this is our guy. Dave Wolf is his name. He's a NASA astronaut.

DAVE WOLF: Have been since 1990, over 20 years.

JAD: He wasn't really sure why we had called him.

DAVE WOLF: What's our topic here?

JAD: So we explained to him that, you know, we're doing this show called In the Dark. We're gonna do it on stage in front of some very nice folks. Do you have any stories that relate? And right off the bat, he says ...

DAVE WOLF: You've triggered an interesting darkness story I have.

ROBERT: Well, that's why we're calling you up.

JAD: Yeah.

DAVE WOLF: Okay, you're taping and you're ready?

ROBERT: Yep.

DAVE WOLF: Darkness is an interesting theme in space, because there's nowhere where the contrast between light and dark is any more extreme.

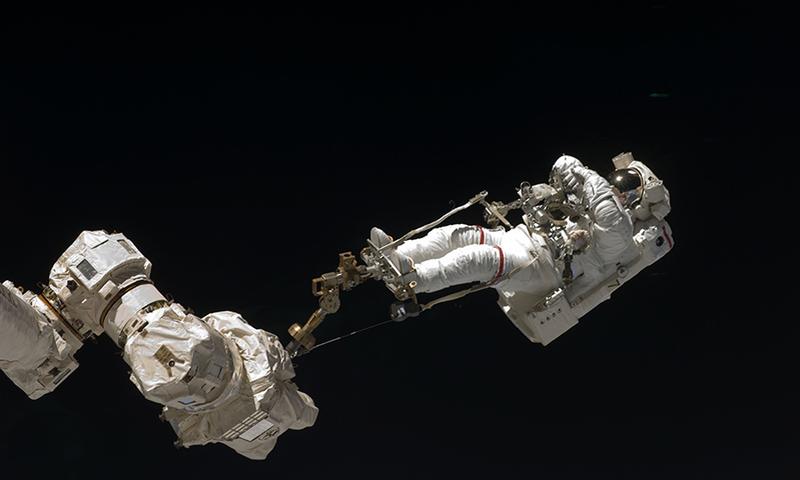

JAD: Dave has done dozens of spacewalks, and he says there have been times when he's just sort of out there floating in space next to the craft, and maybe the ship tilts a little bit and the wing blocks light that's coming from the sun or the moon, and it creates a shadow. And he says the darkness of that shadow ...

DAVE WOLF: Is blacker than any black you thought it could be. Out there in space, the shadow has no light in it. There's not reflected light from dust in the air, the Earth around you or clouds.

JAD: It's just pure, absolute dark.

DAVE WOLF: And you can reach into a shadow so deep, so black, that your arm can appear to disappear.

ROBERT: Wow!

DAVE WOLF: Right in front of your face. Your head is in the bright light, and your arm is in this depth of darkness.

JAD: And it's just gone like it's been cut off?

DAVE WOLF: Yeah.

JAD: Wow!

DAVE WOLF: But I do want to tell you an experience I had in my first space walk. Late '97 I had this experience.

JAD: Okay.

DAVE WOLF: It was from a Russian spacecraft. You might remember the Mir ...

JAD: Yeah, sure.

DAVE WOLF: ... spacecraft.

JAD: So Dave was up there. He was with two Russian cosmonauts, and he and Anatoly Solovyev, they were suited up and getting ready to make their first walk into space—or his first walk.

DAVE WOLF: And we did all the preparations to get the suits ready. And we're in the airlock, and ...

JAD: The door opened, and they floated out.

DAVE WOLF: We clipped our tethers on outside.

JAD: And he and Anatoly gently float to the work site.

DAVE WOLF: And it was dark out. And dark up in space means you're on the night side of the Earth, in the shadow of the Earth. And there were no external lights on this spacecraft. This was really, really dark. And we were over the ocean. And at night, that basically means you don't see the Earth.

JAD: You don't see it at all?

DAVE WOLF: Not at all. When it's a moonless night, you don't see the Earth. In fact, all it might look like to you is the absence of stars.

JAD: I want you to imagine this with me. He's up there in this darkness, and the Earth, with all of us on it, is somewhere far, far below him, but he can't see it. And all the while—and this is really important for what happens next—he is shooting through space. He's rocketing across the dark shadow of the Earth at five miles a second. That is 16 times the speed that we're all moving right now because we are on the Earth. But he says at that moment he didn't feel any of that. It just felt like he was suspended in this cocoon of black.

DAVE WOLF: Floating gently.

JAD: And he thought, "All right!"

DAVE WOLF: No problem.

JAD: "This is kind of peaceful."

DAVE WOLF: Because it was just me and the spacecraft and blackness. And suddenly this blazing light.

JAD: Blasts him from below.

ROBERT: What was it?

JAD: It was the sunrise. You know, because he and the ship were moving so quickly that the sunrise, which normally happens here on Earth very, very slowly, calmly, at that speed up there, the sun comes screaming from the eastern edge of the Earth, straight across the Earth, lights up everything in seconds.

DAVE WOLF: And the Earth lights up below me. Suddenly I can look down 200 miles and see that we're moving at five miles per second.

JAD: Oceans whoosh, clouds whoosh, deserts whoosh. And he was like, "Ahh!"

DAVE WOLF: And I clutched onto these handrails like there's no tomorrow, white knuckled in my spacesuit gloves, because I suddenly had this enormous sense of height and speed.

JAD: He says it was sort of like if you're standing comfortably on the ground, and then someone just flips on the lights suddenly, and you realize actually, I'm not on the ground. I am on a 400,000-foot ladder.

[laughter]

JAD: Crazier still, in that sunrise moment ...

DAVE WOLF: The temperature also increases by upwards of 400 degrees.

ROBERT: In the moment?

DAVE WOLF: In the moment.

ROBERT: Really!

JAD: This is the most extreme thing I've ever heard!

ROBERT: Are you air conditioned or whatever? Are you ...

DAVE WOLF: You are. We are totally dependent on that spacesuit. But the colors, what you're seeing on that Earth is so spectacular—the greens and blues and the delicate, pastel-like colors, the contrast and the brights are just—aren't present in anything I've ever seen other than up in space.

JAD: Dave and his Russian buddy Anatoly, they're out there for hours doing repairs on the ship. So they are—because of their speed, they're going in and out and in and out of these days and nights.

DAVE WOLF: So it's 90 minutes of a light-dark cycle. So you have 16 nights and 16 days for every Earth day.

JAD: Which means as they're working, this change is happening over and over and over. Every 45 minutes, they go from blazing light to quiet dark, blazing light to darkness.

DAVE WOLF: You can get lost. You get stories of people doing spacewalks that lose their orientation or feel like they're falling.

JAD: And so he says the only thing to do in that circumstance is just to focus on your job. Look straight ahead. Only at the screw. Only at the screw.

DAVE WOLF: Don't look down. It's kind of—it's real in this business.

[laughter]

JAD: So we would have been perfectly happy to end the story right here, because Dave and Anatoly finished their repairs. Job well done. They get ready to come back into the spacecraft. But we cannot not tell you what happens next.

ROBERT: Yeah. Because this flirts with a very different kind of darkness.

JAD: Yeah. We'll continue with that story right after the break.

JAD: This is Radiolab. Let's continue now with our story from astronaut Dave Wolf that we performed live as part of our In the Dark tour in front of an audience of about 2,500 people. Where we left off, Dave and his cosmonaut friend Anatoly, they had just been out in space doing a spacewalk, repairing the International Space Station, and they were about to come back in.

JAD: So the two of them pull themselves by their tethers to come back into the airlock to go back in.

DAVE WOLF: But when it was time to come back in ...

JAD: They couldn't get back in!

ROBERT: You were locked out of your spaceship?

DAVE WOLF: You could call it locked out. We were trapped outside. Yes.

JAD: Essentially their airlock was busted. They couldn't repressurize it. And if you can't get it at the right pressure, you can't re-enter.

JAD: Oh no!

DAVE WOLF: And we worked on it for four or five hours, and ran out our resources and we ...

JAD: Wait a second. Ran out of oxygen, or what?

DAVE WOLF: You have plenty of oxygen, it turns out. What you run out of first is your carbon dioxide scrubbing unit that takes the CO2 out of your suit. And now the problem with this one is usually in a space accident, you figure it'll only hurt for a moment. But when you die of CO2 intoxication, that drags out. That's not—that's a miserable way to go.

ROBERT: What does he mean? Did you ever find out?

JAD: I looked it up. What happens is first you get a headache and then your muscles start to twitch. Eventually, your heartbeat starts to accelerate faster, faster, faster. You go into convulsions and then you die.

DAVE WOLF: Luckily, the life support system has an extra cartridge. That gave us an extra six or so hours. We used all that, and—trying to fix the hatch and we couldn't get it to hold air. And we were done.

JAD: Did you know you were done? I mean, you were ...

DAVE WOLF: Yeah. Yeah, pretty much.

[laughter]

ROBERT: And you mean done like in over?

DAVE WOLF: Yeah, yeah. No more ideas.

[laughter]

JAD: Done like in dead. So they decide, "Okay, we gotta do something. Last ditch maneuver. If we can't get our usual airlock to work, maybe we can make a new one." Because see, on the Mir space station, it's this big cylinder with these rectangular modules that jut out. And one of those modules is the airlock. But there are these adjacent ones which are normally just living quarters. They thought, "Well, if we can't get our usual airlock to pressurize at the right pressure, maybe we can go to the next one over and try and pressurize it."

DAVE WOLF: Essentially treating that next module in as a airlock. And we opened the hatch into that next module. And in order, though, to go into it, we had to disconnect our umbilicals, because you can't close the hatch over your umbilical, right?

ROBERT: Right.

DAVE WOLF: And the umbilical was providing our cooling to our suits. So as soon as we disconnected, well, that gives you maybe five-eight minutes at max.

JAD: Before you—before you what?

DAVE WOLF: I don't even want to talk about it. It's so bad.

[laughter]

ROBERT: Did you look that up?

JAD: Yeah, I looked this one up, too. Essentially, what happens is you boil inside your spacesuit.

DAVE WOLF: In a very ugly way.

JAD: So Dave and Anatoly think, "Okay, we've got to get through this tiny hatch into this room." And they've gotta do it fast. But they also know ...

DAVE WOLF: If you struggle hard and go too fast, you won't get much time at all in that suit before that heat builds up on you.

JAD: So he thinks, "Okay, hurry, hurry. But slowly. Slowly."

DAVE WOLF: What I did not anticipate was as soon as we disconnected our umbilicals that the visor would fog up, and you'd now be having to feel your way.

ROBERT: So you're blind?

DAVE WOLF: Yeah. You could spit and kind of get a little area through the fog. So I'm in the airlock, trying to make my way into the next section. And I was crawling along the wall, moving into the next section, and I spit on my visor, you know, to make a little hole to look through and get a hint. And it was an area I had been sleeping in some weeks before. And I had left a picture of my family taped with scotch tape on the wall. And I spit on the visor, and my helmet light went there. And there was this picture of my family right here in this moment as I was scooting across the wall in what was likely my last minutes. So this is how it's going to end. So this is it. And look, it's so strange. There they are. And I look back at that and I shudder.

JAD: Now of course, Dave and his partner made it back into the space station—barely.

DAVE WOLF: But it didn't strike me, really, until months later on the Earth how close that had been, and what a strange situation for us.

ROBERT: This Russian guy must be your best friend. Like, he must be—you call each other and say—20 years later, you go, "Whew!"

DAVE WOLF: Well, not many people have been through anything like that together and are there to talk about it. And you just reminded me of something.

JAD: So we're gonna leave you with one last story from Dave. He was kind of a story machine. This is from that same stay in space, involves the same friend, Anatoly. They were out there doing some work on the ship, you know, floating in space again. And then Mission Control radios and tells them to pause for a while.

DAVE WOLF: We had a period where we had to wait through the night to go on with our work. So he said, "Look, David—" all in Russian, of course. "I wanted to show you something." And we hooked our tethers on, pushed ourselves about six feet away. We had about six feet of tether, so that our eyes couldn't see anything but out in space. And I turned my air conditioner down a little, you know, so it was kind of warm. And I was floating in this spacesuit, just looking out into the blackness of space. And I felt like I didn't have a spacesuit on. It was so comfortable. The air temperature was just right. I felt like I was just out in the universe, in the stars. I couldn't see anything but stars all around me. I couldn't feel anything outside a spacecraft going five miles per second out in the universe.

JAD: Was that what he wanted to show you?

DAVE WOLF: Yeah, I think so.

ROBERT: This is his rocking chair on the front porch thing.

DAVE WOLF: Or a hammock, almost. He didn't want to talk. He said, "Let's just be quiet. Turn your helmet light off so you don't get any reflected light. Just relax. Rasslablyat. Relax. Relax. Relax. Relax. Relax."

ROBERT: Now had you been there in the theater, this is the moment where we gave everybody a little pinpoint of light, a little hand-carried star that they could put over their heads and wave together.

JAD: It was like this canopy of stars.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: Special thanks to the musicians you hear playing with us on stage: Thao Nguyen and Jason Slota. And well, that's it for now.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

[LISTENER: This is Valerie calling from Washington, DC. Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is produced by Soren Wheeler. Dylan Keeke is our director of sound design. Maria Matasar Padilla is our managing director. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Maggie Bartolomeo, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Bethel Habte, Tracie Hunte, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Malissa O'Donnell, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster, with help from Amanda Aronczyk, Shima Oliaee, Jake Arlo and Reid Kanen. Our fact checker is Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.