****************** THIS IS A RUSH, UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT *********************

BROOKE: 25 years ago, the Hubble Space Telescope launched into orbit: its roving camera set to peer into the hitherto unseen depths of the cosmos. ABC’s Peter Jennings on April 24th, 1990.

CLIP:

JENNINGS: this morning if you’d been listening closely to the goings on down at cape canaveral you could have heard the sigh of relief. finally, the space shuttle Discovery is in orbit. in its cargo bay waiting to be put into its own orbit, a telescope so powerful it can see a dime 25 miles away. an instrument bound to contribute to a reassessment of the universe...

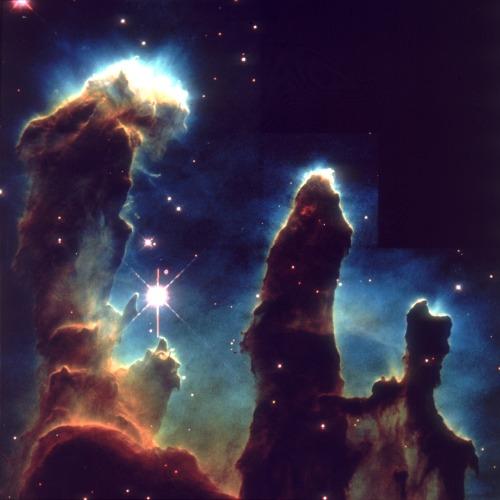

And indeed it has - the Hubble’s images show us star clusters and spiraling galaxies in dreamlike color and vivid detail. Its iconic photo of the Eagle Nebula, and within it, the stunning “Pillars of Creation,” prompted this rhapsodic description 20 years ago in The New York Times, quote, “Bathed in a flood of ultraviolet light from nearby young, hot stars, billowing columns of cold gas and dust rise ominously out of a dark, molecular cloud, like stalagmites from the floor of a cavern. At the tips of these columns, six trillion miles high, gases are so dense that they collapse under their own weight, giving birth to more new stars.”

Elizabeth Kessler is the author of Picturing the Cosmos: Hubble Space Telescope Images and the Astronomical Sublime. She says even if you’ve never knowingly seen Hubble images, you surely have - their vivid hues and stunning formations have shaped virtually every science fiction depiction of space of the last 20 years.

CLIP:

JODIE FOSTER: Some...celestial event. No...no words. No words. [Laughing] To describe…[Crying] They should have sent...a poet. So beautiful. Beautiful. So beautiful. So beautiful. I had no idea. I had no idea. I had no idea….

KESSLER: Contact, based on a novel by Carl Sagan, has a fly through of the eagle nebula that's based on those Hubble images, and that was 1997. So people would have recognized its source. But over time, it's just become integrated into our expectation of what space looks like. Television programs like Battlestar Galactica, sends its battleship through a nebula that's clearly based on views from the Hubble space telescope. Or Guardians of the Galaxy from 2014. You see these kinds of full color views of nebulae, you see these kinds of clouds of gas and dust. Older Star Trek films that predate the Hubble space telescope, the celestial world is full of black and white stars. If you look at Star Trek films that come out more recently, the universe has color.

BROOKE: How are those colors determined? You wrote that through their decisions, astronomers encouraged a particular way of looking at the cosmos.

They want us to experience the cosmos as sublime. And evoke awe and wonder. They know that most viewers outside the scientific community won't understand all the complex mathematical explanations of the size and scale of the universe, but the images can convey some of that to us. They want to invite a sense of transcending the everyday to give us an appreciation for things that are bigger.

BROOKE: But also reachable. They look like places we've never been, but places we could imagine traveling to.

KESSLER: Absolutely. The images very much resemble landscape paintings of the American West, particularly some that date from the 19tjh century. So paintings of places like Yosemite or Yellowstone - these dramatic views by Thomas Moran or Aber Bierstadt, that present strange landscapes in dramatic fashion, and many of the Hubble images look like 19th century landscapes. Their orientation, the ways in which things like the eagle nebula the pillars reach up towards the top of the image, the color choices that result in a blue background --

BROOKE: Yeah they look almost like burnished stone reaching into the sky.

KESSLER: They look like buttes in the American southwest. And that's a comparison that was made in the press release when the Eagle Nebula pillars of creation image was first released by NASA.

BROOKE: What did Galileo's telescope reveal in the 17th century that we'd never seen before?

KESSLER: He turned his telescope to the moon, and interpreted what he was seeing as covered with mountains, instead of as previously though, this kind of perfect, crystalline smooth surface that it was rocky and craggy, just like the earth's surface. And this is part of this shift from seeing the landscape of the earth's surface as evidence of its flawed nature: hey, everything in the universe is like that. One of his other big discoveries of course, is that Jupiter has moons. Seemingly black empty space, was actually full of galaxies. The Hubble space telescope images by introducing this play between the alien and the familiar, it lets us imagine the universe as something within our reach, even as it retains that sense of its vastness and alienness and strangeness and distance. This realization that our sense are limited, but yet our mind has this extensive possibility, and that's where the pleasure of the sublime comes in.

BROOKE: Let's talk about the sublime. It's defined as a tension between the senses and reason. An extreme aesthetic experience, one that threatens to overwhelm, even as it affirms humanity's potential. This is I guess Kant's view of sublimity. Now, you've noted that in the history of visual culture in Europe, these landscapes, these dramatic mountain scenes, were places to be frightened of.

KESSLER: Yeah, if we go back through the history of western visual culture, mountains weren't to be admired. They were frightening, threatening places, and even indications of the fallen state of the earth. But as we move into the 19th century, there' a greater and greater appreciation for the experience of the sublime. And Kant talks about the impossibility of ever seeing something like the infinite. Our senses always falter and fail if if we were to try to see the infinite. We cannot. But yet our mind can conceive of it, if we connect that to the hubble images, here it is this really strange alien world and we are so tiny, if we could fly out to the eagle nebula, we wouldn't even show up in the Hubble's picture, we would be so small. Yet, we have the capacity to develop an instrument that lets us take a picture and reach towards it even as our senses end up not measuring up to all its size and complexity and vastness.

BROOKE: Don't you think it's striking as an art historian, that despite revolutions in technology, earth culture still sees the frontier the way it first appeared to us when we were, you know, living in trees: deep canyons, tall mountains, vast earthly expanses that got transposed through the Hubble onto the cosmos.

KESSLER: Well, our biology hasn't changed: we're still beings that stand on two legs and look up at things that are bigger than we are. Things like the grand canyon are young if we're thinking about cosmic time. But it's the best representation of time that extends so far beyond our human experience. And so it becomes our only analogy for trying to understand the time and the space and the distance and the vastness and the scale of what the Hubble images show us.

BROOKE: You know what's interesting is that the pillars of creation which so define how we see the cosmos ceased to exist a millennium ago.

KESSLER: Yeah, so I hear. It's another sort of twist on time: so we're already behind. Our imaginations haven't caught up to what's actually happening in the cosmos.

BROOKE: Elizabeth, thank you very much.

KESSLER: Oh I'm happy to talk, thank you very much for having me.

BROOKE: Elizabeth Kessler teaches at STanford and is the author of

Picturing the Cosmos: Hubble Space Telescope Images and the Astronomical Sublime.

BOB: That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Kimmie Regular, Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova Burgess, Ethan Chiel, Kasia Mihailovic and Jesse Brenneman. We had more help from Jenna Kagel. And our show was edited by…Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Greg Rippin.

BROOKE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for news. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB: And I’m Bob Garfield.