BOB GARFIELD: Amid the furor over the Michael Flynn firing this week, came a profoundly serious judgment about him and even the president, himself.

LAWRENCE O’DONNELL/MSNBC: Treason, it has come to that, treason. We now have to discuss treason because Donald Trump did something this weekend that we've never seen before.

FORMER REP. JOE WALSH: For Donald Trump to come out and attack our men and women in the CIA, I, I - that's almost treasonous.

STEPHEN COLBERT: And now, The Late Show presents Valentine’s Day cards with Michael Flynn.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER]

To: President Trump,

I will never resign from being your valentine.

[LAUGHTER]

To: Vladimir Putin,

We go together

Like peanut butter

And treason.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER/END CLIP]

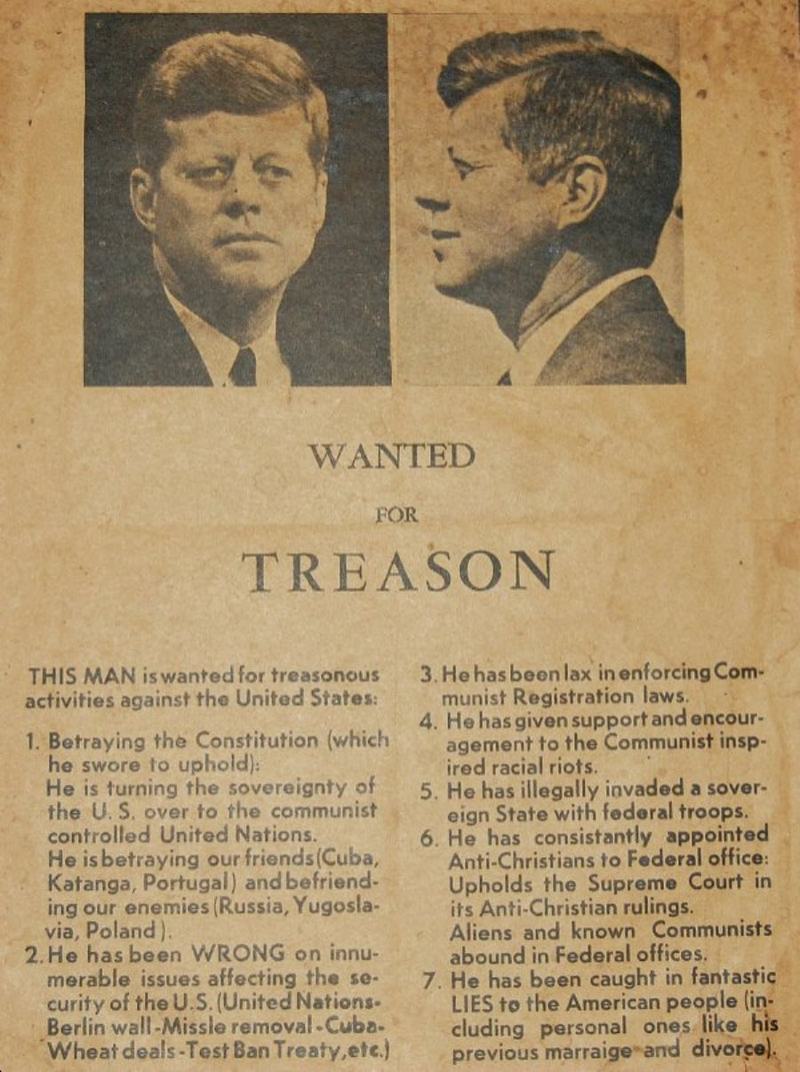

BOB GARFIELD: Treason, the highest of high crimes, punishable by death. But don't start erecting a presidential gallows just yet. Jed Shugerman, a professor of law at Fordham University and author of the blog, Shugerblog, says the accusation has been lobbed too loosely for centuries.

JED SHUGERMAN: Because the word “treason” had been abused in medieval England, a statute was passed in 1351 to purposely limit the word “treason” and it's that same language that our framers used in the Constitution.

BOB GARFIELD: Because they had all been tarred with that very label while they were revolutionaries.

JED SHUGERMAN: That's right. Even look at the words they use to define themselves. The loyalists were framing themselves as loyal against the treason of the colonists. And so, that's why in the Constitutional Convention there is very strong consensus in favor of using this narrow definition of treason in

Article 3.

BOB GARFIELD: So what precisely would amount to treason?

JED SHUGERMAN: It’s pretty concise and clear in the Constitution, so let me just read it to you. “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them (against the United States), or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.” So that language is purposely limiting the definition of treason to levying war and enemies. And to be clear, that word “enemies” had an understanding clearly at the time about wartime because otherwise the use of that word “enemy” if it wasn't wartime, you would have a political battle over whether Russia is an enemy.

BOB GARFIELD: Let's discuss that because this is a nation that is sometimes a partner, most recently an adversary, in something that has increasingly resembled the days of the Cold War. So you could probably make a forceful argument, especially if you count all the missiles that are aimed approximately in our direction, [LAUGHS] that Russia is an enemy and colluding with them, if that could be proven, would be giving aid and comfort to one.

JED SHUGERMAN: That’s a great question but I think it’s also precisely the problem. We could come up with, throughout American history, lots of examples where one faction in the United States looks at an international rival and says, well, we have a rivalry with that country, let's call that country an enemy. We can then look at the people who are in contact with that country, the people who are negotiating with that country and we’ll use treason to crack down on them.

BOB GARFIELD: In our current circumstances, the word has been the go-to accusation from the anti-Trump left. It seems like just yesterday [LAUGHS] that it was the accusation of choice from the right against Hillary Clinton for her careless use of a private email server.

[CLIP]:

REP. MICHAEL T. MCCAUL: She exposed it to our enemies and now our, our adversaries have this very sensitive information that not only jeopardizes her and national security at home but the men and women serving overseas. This is - in my opinion, quite frankly, it’s treason

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: What happens to a legal term, a narrow one, when it becomes the O-negative for all kind of political purposes?

JED SHUGERMAN: It takes a political disagreement about foreign policy and it criminalizes that disagreement. In World War I, the use of the prosecution for treason was exploited against the left, who were using free speech to oppose the draft. Even though it wasn't directly giving aid and comfort, so many different organizers, labor activists were charged with treason, exploiting in wartime domestic political disagreements. The problem in this moment is that if both sides start throwing around this word, it takes the hyper-partisanship of criminalizing political disagreements and escalates it.

BOB GARFIELD: You also discussed the problem with reflexive use of “treason” as a strategic blunder. Why is it that?

JED SHUGERMAN: I think it's a strategic mistake because if the steps now are to look at the investigation of the Trump administration, there needs to be more consensus, not just the left and not just the Democratic Party that's calling for investigations. There is a struggle to convince the public that this isn't just a partisan witch hunt but it's really about the rule of law. And if we’re going to make arguments about the rule of law, then we need to use the right legal terms and think about what's going to be more persuasive and generate more consensus to move forward.

BOB GARFIELD: What language do you propose or what statutes do you suggest are relevant that can take some of the partisan heat off of this question?

JED SHUGERMAN: We don't know yet enough of the facts. That’s why we need the investigation. But if the Trump campaign and if Donald Trump himself knew about not just the hacking of emails but other confidential material, I think conspiracy, obstruction of justice, those legal terms are, I think, legally correct and strategically wise.

BOB GARFIELD: Jed, thank you very much.

JED SHUGERMAN: I’m always happy to talk to you, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Jed Shugerman, author of Shugerblog, is a professor of law at Fordham University.