The Birth of Climate Disinformation

( Blackbetty44 / Wikipedia Commons )

SACHA PFEIFFER We heard Hertsgaard say that fossil fuel companies have been lying to the public for decades. In fact, it's well documented that almost as soon as climate change became a scientific reality, they actively downplayed the crisis. But to keep Americans unaware of the growing urgency of our environmental problem, those same companies needed a way to paint themselves as heroes. Advertising allowed fossil fuel companies to sell themselves, not their products, as the good guys. The depictions of billion dollar companies were often folksy, innovative, innocent and brazenly, stereotypically American. The strategy was genius. It's also now the subject of congressional scrutiny. This week, the House Oversight Committee officially launched an investigation into the fossil fuel industry's disinformation efforts and their impact on the climate crisis. Journalist and podcast host Amy Westervelt wanted to go back to the beginning to find out how advertising the media and the fossil fuel industry became so intertwined. Her podcast Drilled, profiled several of the men who invented the public relations business we know today. The following is an excerpt from one of those episodes.

[CLIP]

HERB SCHMERTZ If you're going to do the job properly, you have to find unconventional ways to communicate to the public. And it's not a question of convincing the press of anything. It's a question of convincing the public [END CLIP]

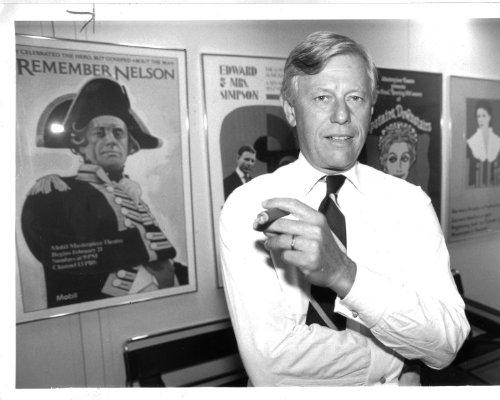

AMY WESTERVELT That’s Mobil Oil's legendary PR guy, Herb Schmertz. Schmertz was VP of public affairs for Mobil for decades. Slick and handsome, always with an expensive suit, he was the smartest guy in the room and mostly thought that both journalists and other PR guys were idiots. He ran PR for Mobil Oil from 1969 to 1988 and became a master of media manipulation. Schmertz didn't just focus on placing particular stories he set about fundamentally changing the relationship between corporations and the media. To Schmertz, the press was more of an obstacle between him and the public or Mobil and policy makers.

[CLIP]

HERB SCHMERTZ And to do the job properly, you have to really go around the press or beyond the press or against the press to get a story out so that the public focuses on it, not the press. If you're just going to limit yourself to getting the press to focus on it, you're not doing the entire job. [END CLIP]

AMY WESTERVELT Schmertz is the guy who really turned media into another propaganda tool for the fossil fuel industry. He invented the advertorial for a start. He also invented issue advertising, which is now the only type of advertising the oil industry does. You'd think all they do is farm algae and research carbon capture and worry about climate change if you only paid attention to their ads.

[CLIP]

EXXON MOBIL ADVERT Energy is a complex challenge. People want power and power plants have more than a third of energy related carbon emissions. The challenge is to capture the emissions before they're released into the atmosphere. Exxon Mobil.... [END CLIP]

AMY WESTERVELT Schmertz, also bullied journalists into covering big oil’s side of the story, and he encouraged his peers to do the same. Which, sadly, worked really well, and he lobbied for corporate First Amendment rights and against any media regulations that would make it harder for him to use the press as a tool. Known during his heyday for dapper suits, cigars and generally being something of a dandy. For the first half of his life, Herb Schmertz seemed more destined to be secretary of labor than a famous PR guy. After graduating from Columbia Law School in 1955, Schmertz was drafted into the Army. The Vietnam War was just beginning, given his law background, Schmertz was sent straight to work in counterintelligence in Washington, D.C. After 2 years there, it was back to law for Schmerts. Labor law, following in the footsteps of his older brother. In 1960, Schmertz signed on to work for JFK's campaign.

[CLIP OF JFK AD PLAYS, CHORUS SINGS "KENNEDY" REPEATEDLY]

AMY WESTERVELT He was a Democrat, an idealist, and he helped the campaign with voter registration and reaching out to special groups. Including labor and various ethnic communities in New York. When he went to work for Mobil, commerce is actually still working in labor. He handled the company's labor relations for 5 years, but his background in law and political campaigning, combined with his relationships with various labor unions, made Schmertz an even greater, if unexpected, fit for the company's public affairs office. By this point, 1969, Mobil's CEO was a man named Rawleigh Warner. Warner wanted Mobil, which always seemed to be playing catch up to Exxon, to be more of a visible player in the industry. Schmertz had a lot of ideas on that front, starting with humanizing Mobil. Giving the company a personality, complete with ideas that needed to be shared. Here's Schmertz much later in life, describing that strategy.

[CLIP]

HERB SCHMERTZ As a personality where we believe very strongly about the importance of public policy. We believe fervently that as custodians of vast resources and one that we were not doing our job if we did not participate in the marketplace of ideas [END CLIP]

AMY WESTERVELT To get all the facets of the corporation's personality across to the public, Schmertz used the tools he's come to be known for. The issue ad and the advertorial. The latter was born in 1970, when the New York Times opened up its op-ed pages to advertising for the first time. Schmertz wanted Mobil's ad to be just as smart and provocative as any editorial that might appear in the section otherwise. He hired legit writers to write them and eventually ran them every week for decades. They ran the gamut from squawking about taxes, to complaining about the media, to unexpected takes in favor of public transit. Schmertz talked about one of his advertorials on the PBS show The Open Mind in 1980.

[CLIP]

DAVE Herb, thanks for joining me today.

HERB SCHMERTZ A great pleasure to be here Dave.

DAVE I want to turn as quickly as possible to a new fairy tale, the Mobil ad or op ed piece or editorial, call it what you will ...

HERB SCHMERTZ We call them, pamphlets,.

DAVE Pamphlets, but they appear in newspapers.

HERB SCHMERTZ Yes. [END CLIP]

AMY WESTERVELT A new kind of fairy tale was the title of Schmertz's latest advertorial, and it criticized PBS for running a film that stereotyped Saudi Arabians. It was, of course, in Mobil's interest to be seen as a friend and staunch defender of Saudi Arabia. At this point in time in particular, the company was increasing its profits mainly by expanding its development and production in Saudi Arabia.

[CLIP]

DAVE At the end, your conclusion in the ad, wehope that the management of the Public Broadcasting Service will review its decision to run this film. Meaning you hoped they wouldn't run it.

HERB SCHMERTZ Well not necessarily [OVERTALK]

DAVE ...and exercise responsible judgment in the light of what is in the best interest of the United States.

HERB SCHMERTZ Right

DAVE Do you think they did exercise responsible judgment?

HERB SCHMERTZ I think they did a better job after this ad period than they otherwise would have, but they could have done substantially more [END CLIP]

SACHA PFEIFFER Driven, at least in part by this advertorial, PBS aired a panel discussion following that film where Mobil's position was represented alongside other voices.

AMY WESTERVELT In various documents and speeches, Schmertz referred to how they helped shape the discourse on key issues to the company and established mobile as the thinking man's oil company. In a long buried briefing that we found called the Corporations and the First Amendment that Schmertz wrote for the American Management Association in 1978, he explains why he chose The New York Times for these ads. He writes, quote, The Times was chosen because it is published in the nation's leading population communications and business center. Because it has a highly intelligent, vocal, sophisticated readership and because it reaches legislators and other government officials. In short, it was the paper most likely to reach the largest number of opinion leaders and decision makers. Schmertz also talks about the program as a great success, in this briefing. "Mobil found that the medium worked," he writes. "The messages stimulated discussion among influentials on both sides of the issue. Exactly what the company had set out to do." But it turns out that the result of placing all those ads was quite different from simply stimulating discussion, not just in terms of reaching a large audience of readers, but also in shaping the Times his own coverage of these issues.

KERT DAVIES They talk about having influence The New York Times editorial viewpoints.

SACHA PFEIFFER Kert Davies is the founder and director of the Climate Investigation Center, a nonprofit watchdog group that focuses on influence around energy and environmental policy. They uncovered an internal marketing report from 1982 in which Mobil's marketing and PR team was reporting to the company's leadership about how these advertorials had done.

KERT DAVIES The document says, quote, our analysis shows that the Times has altered or significantly softened its viewpoints on conservation, moving from a total reliance on conservation to advocating increased production incentives to solve the supply shortage on monopoly and divestiture. Moving from approving the breakup of the oil companies to opposing divestiture. Moving from advocating strict environmental safeguards to suggesting more relaxed controls on offshore drilling. Moving from valuing environmental concerns at the expense of exploration and development, to urging accelerated offshore drilling. So they are tallying how they have affected the viewpoints of The New York Times on conservation, monopoly and divestiture. Decontrol, natural gas, coal, offshore drilling, all things that they had written op eds on.

GEOFFREY SUPRAN And they've been open and forthright about this, even in some of the editorials themselves.

SACHA PFEIFFER Harvard science historian Geoffrey Supran has studied these advertorials at length.

GEOFFREY SUPRAN No doubt the fossil fuel industry has been very effective at embedding themselves into our culture and our society and our media in an increasingly insidious way that makes it hard to discern when you are being advertised to, versus simply being reprogrammed to see the world and society in a slightly different way.

AMY WESTERVELT Mobil was convinced enough that its advertorial strategy worked, to keep running them weekly in the Times for decades. It was even a program that Exxon kept going after it acquired Mobil.

GEOFFREY SUPRAN They've taken out about one in four of all the advertorials that have ever appeared on the op ed page of The New York Times.

AMY WESTERVELT He said one in four. So 25 percent of all advertorials that have ever run in the New York Times op ed pages were commissioned by Mobil or ExxonMobil.

GEOFFREY SUPRAN Political scientists studying these efforts have described this campaign as towering over all other competitors in its volume and expense.

AMY WESTERVELT ExxonMobil doesn't run its advertorials anymore, but it's moved on to the latest iteration. Campaigns made by The New York Times itself. It's not the newsroom, it's the brand studio that The New York Times created, but still, it's the same company that puts out The New York Times newspaper – making oil companies ads for them. See if you can spot a bit of the Schmertz magic here. In 1978, he said the goal of Mobil's advertorial campaigns was to, quote, stimulate discussion among influentials. In 2020, The New York Times brand studio website's tagline is, quote, stories that influenced the influential. Here's a campaign they did for ExxonMobil last year. Highlighting the company's algae biofuel program.

[CLIP]

ALGAE BIOFUEL ADVERT These vibrant green dots, microscopic living organisms are algae. Look closely, algae grows almost everywhere from murky ponds. [END CLIP]

AMY WESTERVELT Again, the brand studio is separate from the newsroom. There's a definite firewall between advertising and editorial. And every time I talk about these campaigns, New York Times reporters bristle at the idea that they are being accused of being manipulated or influenced by industry. Whether they are or aren't influenced is not really the point. It's not even the goal of these campaigns. The goal is to reach and influence certain types of readers and to wrap the industry's messages in the cloak of credibility provided by The New York Times or The Washington Post, which also does this. Last year, The Post ran a series of stories that its brand studio created for the American Petroleum Institute, all about how, quote, natural gas and oil are helping to deliver a sustainable fuel mix. These campaigns are worth hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for newspapers at a time when the business model for journalism has never been more strained. And when you ask for proposals on them, as I did, ad sales, people start offering all kinds of things. You could place content they write for you in the climate section. You can peg it two key words like climate change and make sure it's a suggested next read on any related news story. Influence doesn't look like an oil tycoon in a top hat showing up at your desk to twirl his mustache and tell you to spike a story. It looks like readers being fed a bunch of oil propaganda before, after and right next to your legit climate reporting. We have Herb Schmertz to thank for that.

SACHA PFEIFFER That was an excerpt from the Mad Men season of Drilled, an Investigated podcast about climate change hosted by Amy Westervelt.

That's it for this week's show on the Media is produced by Leah Feder, Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Rebecca Clark-Callender and Molly Schwartz with help from Juwayriah Wright. Xandra Ellin writes our newsletter. Our technical director is Jennifer Munsen. Our engineer this week was Adriene Lilly. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios, Brooke Gladstone will be back in two weeks. I'm Sacha Pfeiffer.