BOB GARFIELD: Back to the subject of scandal and the practices used to report it. It turns out the phone hacking by Rupert Murdoch's News of the World did not mark a new low for journalism.

Arguably, that mark may have been hit in the summer of 1897, when the body parts of New York masseur William Guldensuppe began

turning up all over the city, except his head. Eventually the grisly crime was blamed on Guldensuppe’s lover Augusta Nack and her lover, Martin Thorne.

And that particular summer, William Randolph Hearst had launched a new evening edition of The New York Journal, and he was determined to trounce his main competition, Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, by owning the Guldensuppe murder.

Last summer I spoke with Paul Collins, author of The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime that Scandalized a City and Sparked the Tabloid Wars.

PAUL COLLINS: Initially, the police were actually not inclined to pursue the case because they thought that they wouldn't be able to solve it. There was no crime scene, there was no clear identity on the body. And it was really the newspapers that solved it. They were the ones that started throwing reporters into it, having them scour the city to try to find who might be missing.

The papers really very actively inserted themselves in the case, in such a way that it - it almost certainly wouldn't have been solved without them.

BOB GARFIELD: But along the way, broke the law, violated any sense of –

PAUL COLLINS: [LAUGHS] Oh yeah -

BOB GARFIELD: - professional ethics.

PAUL COLLINS: [LAUGHS] All the papers were covering the story but the two that really went head to head and kind of defined it were Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

Pulitzer had his people offer a reward to readers for any clues. They stole evidence from one of the crime scenes. When they found a likely murder scene, they actually gouged out a piece of the floor board to have it tested for blood.

One of their cub reporters, when he found the likely identity of the victim out, actually visited the house before the police did, talked to Mrs. Nack, one of the people in this love triangle. He was actually posing as a soap salesman and gave her a sample to try out in her kitchen, and while she was in the kitchen he stole a photo off of her mantle that he figured was probably William Guldensuppe.

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHS] Oh my goodness. You know, I’m sorry. I apologize. I left subterfuge and theft out of the list –

PAUL COLLINS: Yes [LAUGHING]

BOB GARFIELD: - of criminality that I - I gave you before.

PAUL COLLINS: The World was pretty [LAUGHS] impressive in what it was willing to do but Hearst actually managed to top them almost every step of the way.

When they first got word of Mrs. Nack’s apartment as being this likely crime scene, Hearst personally went over to the apartment. Her lease on the place had actually just run out. And he went to the landlord of the building and offered him an immense sum of money to lease out the crime scene, to lease out the apartment, and then proceeded to only allow Hearst reporters and police into the apartment.

And he also had other [LAUGHS] staff go to all the local pay phones to cut the cords, so then when they got to the scene and found they couldn’t go in, went to a pay phone to try to call their newsroom, they would just pick these receivers and the cord would just be hanging.

BOB GARFIELD: But, of course, Augusta Nack and Martin Thorne were arrested for conspiring to murder William Guldensuppe. And, naturally, both Pulitzer and Hearst decided to let justice take its course, right?

PAUL COLLINS: No, it got worse. [LAUGHS]

[BOB LAUGHING]

At, at that point they were sending reporters constantly into the - into the jail. Mrs. Nack was trying to send a letter to Martin Thorne who was in the same jail. She was using what was known as a trusty, actually another prisoner that the warden gave special privileges to ‘cause he was non-violent and, and trusted basically. Mrs. Nack gave him a letter hidden inside a sandwich and told him to take it to Martin Thorne.

Instead, he waited ‘til the warden sent him out on an errand outside the jail. He went straight to The Journal's newsroom and gave them this letter. They then copied the letter and allowed it to go onwards to Martin Thorne, who destroyed it.

BOB GARFIELD: Hacked voicemails, 1897 style.

PAUL COLLINS: Yes. [LAUGHS] The attorney general was not amused.

BOB GARFIELD: So when did the yellow press actually turn into physical tabloids?

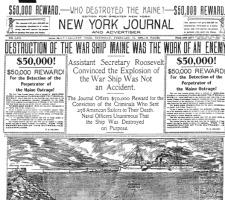

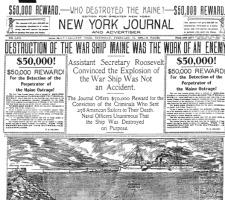

PAUL COLLINS: One thing I noticed when I was looking at The New York Journal was that by the turn of the century it started to actually look different. The ratio of the paper had gone from 1.4 to 1.25 in just a few years. It actually was getting more and more square and Hearst started using giant headlines for everything.

At first he would have six-inch tall headlines for a war starting, but by the turn of the century Hearst was using them for everything. You know, the building collapse, someone gets murdered in Union Square, anything like that would have these giant screaming headlines.

So although tabloids sort of proper really got fully underway in the 20s, even by the turn of the century you could already see things moving in that direction.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, it clearly has evolved differently in the United States than it has in the U.K. You - you could argue that The New York Post and The Daily News are kind of low brow and, and populistic, and they don't shy away from a big colorful crime. But they're also not News of the World or The Daily Mail.

What happened historically that the U.K. versions of tabloid sensationalism and the more muted U.S. version diverged?

PAUL COLLINS: I think that there was a great deal of worry over Hearst’s influence after the Spanish-American War. He kind of parlayed this, this power that he had into the support of the war, to the point where he actually fought in a battle in Cuba. He also offered to pay for a regiment. Clearly, he was taking on a pretty disturbing role.

One of the people, strangely enough, who seemed to be especially disturbed by this was Pulitzer, who after trying to keep up with Hearst, actually started to back away from what he had helped create and helped fund the Journalism School at Columbia, funded the Pulitzer Awards, of course, and so, left a very different legacy.

Hearst’s influence really manifested itself much more with Lord Northcliffe in Britain who was sort of a - an intermediary figure between Rupert Murdoch and Hearst. That influence has become much more manifest, I think, in Britain and in Murdoch's empire.

BOB GARFIELD: So you think that Rupert Murdoch is the kind of moral successor to William Randolph Hearst?

PAUL COLLINS: I think that they are very similar in many ways, one of which is that most biographers of Hearst didn't seem to regard him as immoral so much as amoral. He was just interested in selling newspapers and in extending his influence.

And a lot of the strategies that Hearst did of turning news into a narrative, picking some stories and covering them nonstop, bringing in lots of talking heads to keep a story rolling, even when there's no new developments, is completely recognizable today.

BOB GARFIELD: Yeah, it’s the FOX News Channel.

PAUL COLLINS: Yeah. They very much have inherited the Hearst tradition.

BOB GARFIELD: Paul, thank you very, very much.

PAUL COLLINS: Oh, thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Paul Collins is associate professor of English at Portland State University and author of The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime that Scandalized a City and Sparked the Tabloid Wars.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]