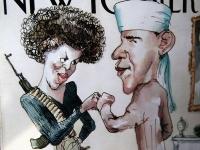

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This week, we’re talking about stuff we think we know about but, in fact, we don’t know. From our archives we’ve pulled stories of debunkings of stories great and small that have served as cultural signposts sending us in the wrong direction. Some of these stories seem impervious to change because we like them as they are. They make sense to us. They fit in with what we think we know. Brendan Nyhan is a blogger and political scientist at the University of Michigan. Last year he was part of a team that studied how people so easily ignore corrections to the record. One study tested a new way to blow past our inborn barriers but it seems to have fizzled too. Brendan, welcome to the show. BRENDAN NYHAN: Thanks very much. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, this study is building off previous research that you've done on correcting misperceptions, research, in fact, that we've covered on the show. But can you give us just a quick rundown of what those earlier experiments showed? BRENDAN NYHAN: Sure. My coauthor, Jason Reifler, and I looked at can the media effectively correct misperceptions, which seems like a simple question, but no one had really tested that scientifically. BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you found actually that when people had their misperceptions challenged certain people, at least, were more likely to become more firmly entrenched in that belief. BRENDAN NYHAN: That's right. People were so successful at bringing to mind reasons that the correction was wrong that they actually ended up being more convinced in the misperception than the people who didn't receive the correction. So the correction, in other words, was making things worse. BROOKE GLADSTONE: So tell me about your latest study. BRENDAN NYHAN: What we wanted to understand was whether it was possible to correct the misperception out there that Barack Obama is a Muslim, which has been shown to be held by 10 to 12 percent of the public, and another 25 to 35 percent isn't sure if he is a Muslim or not. So what we wanted to do was to see is it possible to correct that misperception. BROOKE GLADSTONE: And something that we already knew is that you can't say Barack Obama is not a Muslim, that by simply offering the denial, you get nowhere because people tend to forget the “not” and the original statement in all its glorious wrongness is merely reinforced. BRENDAN NYHAN: That's right. The “not” seems to fade away. The canonical example in politics is Richard Nixon saying, I'm not a crook, and after a while people started associating “Nixon” and “crook.” So we thought the same principle would apply to Obama saying, I'm not a Muslim. What we wanted to do was to test the approach of saying, I'm not a Muslim against an alternative, which is to say, I'm a Christian. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sounds like a perfect plan. BRENDAN NYHAN: It only worked some of the time. When non-white students were interviewing respondents to the study, the message seemed to work, and, in particular, with Republicans, the group that was most likely to hold the misperception. But what happened when it was only white students administering the experiment was precisely the opposite; the correction appeared to actually make things worse. BROOKE GLADSTONE: And did you assume that when they said that they believed him, when talking to your students who are not white, then your subjects were lying? BRENDAN NYHAN: We don't know if they were lying, but we do have evidence from a tool that tries to measure people’s associations - in other words, their unconscious perceptions of Obama - that when the non-white students were present, people were giving responses that didn't line up with their unconscious associations. BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s a nice way of saying you’re suspecting that they were lying. BRENDAN NYHAN: [LAUGHS] Well, I'm hesitant to use the L word, but it seems that it may have created an environment that people weren't comfortable saying what they really thought. BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, we'll be talking later in the show about the tendency of people to lie about their own racism to pollsters - the Bradley effect is actually a myth. BRENDAN NYHAN: That's right. That’s a very interesting study. It may be the fact that our experiment was conducted in person, whereas most of the polls that go into these studies of the so-called Bradley effect are conducted over the phone. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. Now, you've spent years doing studies on correcting misperceptions and you also ran Spinsanity, which is a political factchecking website that was a precursor to sites like FactCheck and PolitiFact. What do you think is the best way to combat misperceptions? BRENDAN NYHAN: When we were working on Spinsanity we had a group of readers who were very interested in finding out about political spin, and even then it was incredibly difficult to get them to accept corrections that targeted the side that they liked the best. So you can imagine how hard it would be with the general public. So what I think is the most effective approach is to go after elites, to shame the people who are promoting these things, who are putting them out there. BROOKE GLADSTONE: You’re talking about the punditocracy and politicians, and you’re talking about going to the wellspring of these misperceptions? BRENDAN NYHAN: That's right. One of the things we tried to do at Spinsanity was just to show in excruciating detail how frequently people like Ann Coulter and Michael Moore distorted the facts. And at some point, people have to be cast out of polite society. You have to simply say, that is irresponsible and we're not going to give you our air time, our print to make that sort of a claim. Politicians and talk radio hosts, they're going to push these things when it’s in their interest to do so. It’s a simple cost-benefit calculation. What I want to do is increase the cost. BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Brendan, how is this supposed to work? I mean, you’re talking about people like Ann Coulter. Surely you’re not going to be shaming these people. BRENDAN NYHAN: They're hard to shame, but we give them access to the megaphone, and the media has to exercise some responsibility in who gets air time. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can you give me one example where this worked? BRENDAN NYHAN: [SIGHS] Oh, geez. [LAUGHS] Um - BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah, I thought so. BRENDAN NYHAN: [LAUGHS] “Weapons of mass destruction” is better than it was in the aftermath of the war. People who believe that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction - it’s still out there, but it’s a lot smaller than it was. BROOKE GLADSTONE: The reason why I'm asking this question is because this week we're looking back at some enduring myths that have been perpetuated by the media that have been very hard to dislodge. How hard should we be working to correct the historical record, or is it just a Sisyphisean enterprise? BRENDAN NYHAN: There are things that at some point you have to just say, it’s water under the bridge and we can't undo the damage that we've done. But there are others that keep coming back up. The Obama Muslimist perception is underpinning all sorts of claims and insinuations that are still being made, so there is a continuing relevance to the misperception, and that’s why it’s so important to keep fighting it. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Brendan, thank you very much. BRENDAN NYHAN: Thank you, Brooke. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Brendan Nyhan is a blogger and a political scientist at the University of Michigan.