Panoramic View

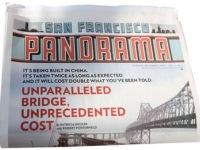

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This past December, writer Dave Eggers’ publishing house, McSweeney’s, released a newspaper called Panorama. But unlike typical newspapers, it was a lustrous and meticulously designed broadsheet edition of 320 pages, featuring long investigative pieces, a 96-page book review, a magazine, full-page color comics and lengthy takeouts by such luminaries as William T. Vollmann and Stephen King. Also, unlike newspapers, it was intended to come out only once. This week I interviewed Eggers at the Conference of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington. He said he began his project to reinvigorate the many journalists still at work in the medium.

DAVE EGGERS: And I have so many friends that work at newspapers all over the country and world, I – and we were talking all the time about people losing their jobs and shrinking staff, shrinking news holes and, you know, a sense of – a sense that there needed to be an injection of optimism, I think, about the print form. And I kept saying, no, it can work, it can work, and people still love print. And so, one of the major factors was to demonstrate what print can do uniquely well and make it distinct from the Web.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s no question that it’s a gorgeous demonstration of what can be done with print journalism, given the staff and the money. But with both of those resources in short supply in the typical newsroom, I wondered what lessons Panorama could hold for the audience of daily news editors. What has this to tell newspaper editors? This is a paean to print. It’s an homage to the broadsheet. But, in a way, it’s got very little to do with the business of journalism day to day. How much do you think the Cleveland Plain Dealer would have to pay William Vollmann for 17,000 words?

DAVE EGGERS: I – no, I don't agree. I think it’s replicatable. Nobody asks William T. Vollmann to fly down to Imperial County because we assume it’s going to cost us 20,000 dollars, and that’s not necessarily the case. I think so many writers, if given the opportunity, and the space, and that audience – Bill Vollmann, you know, his books don't sell hundreds of thousands of copies. If a paper with a 300,000 dedicated circulation every day says, you know what, we're going to give you an eight-page section to talk about something vital, I mean, I know for a fact, because we asked – there’s over, you know, there’s about 200 contributors to this project – everybody leapt at it, not just because it was friends or anything but because we said, we're going to give you an expansive amount of space. And I think that that’s something so lacking. Everybody gets paralyzed with the fear that they're going to get most of what they write chopped in half, for space alone, not for clarity or any other reasons. But if you say, you know, we're going to let this breathe a little bit. You can attract, especially right at this moment, you can attract people that otherwise, in the days when Esquire, GQ, all of these other magazines had much more space for the literary journalism - that doesn't exist as much anymore. So I think The Cleveland Plain Dealer could do the same thing, you know, have this writer on this subject and no one else has it. I don't know, it’s a reason to pick it up and pay for it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was passed up to me that ASNE really wanted me to ask about leadership. How do you get these people to volunteer to work for free, to cluster around your effort? And I thought it’s like asking George Clooney how he gets all those girls.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER] I mean, the fact of the matter is it helps if you write a bestselling novel that’s the seed of a new aesthetic, that makes irony no longer detached, that unites irony with passionate engagement and then to naturally draw people who share those passions to you.

DAVE EGGERS: It has nothing to do with me. And there was very little volunteer labor, I have to say. Our editors were all paid. On the outskirts there were interns that were helping out, but everyone was paid.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You said it was 70,000 editorial?

DAVE EGGERS: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Seventy-thousand dollars and a 350-page paper, over eight to nine months to produce?

DAVE EGGERS: The only people working eight to nine months were me and one other guy. Everybody else, it was more like five weeks.

[OVERTALK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm, eight to nine months is a long time for two people to -

DAVE EGGERS: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - you know, to – Something that’s here isn't adding up for me. I mean, maybe I just don't -

[OVERTALK]

DAVE EGGERS: I can do all the math. It’s real math. I got to tell you, and like I, I hear that from all my friends: Well, the math, rah-rah-rah! The math works, and I can apply it to anybody’s circulation model. All of you who use freelancers, you might pay 250 for this, you might pay 500 for that. I mean, that’s affordable, right? And we were paying more than that for a fraction of the circulation. So freelance shouldn't be as a substitute for staffers, but if a whole city, like San Francisco or New York or all these cities have so much talent that I don't think we need to create an un-hurdle-able wall between all of the writers and novelists and freelancers in a given city and our daily staff.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s been so much said about the new relationship between news consumers and news producers, how this is no longer a one-to-many relationship, but it goes back and forth. What do you think about that?

DAVE EGGERS: I want a printed newspaper curated and edited by professionals that have been in the trade for decades, if possible. I am in internal deference to expertise. At the same time, I think that there is opportunities. We had this guy, Wajahat Ali, who was an attorney, who was a playwright and wrote about his adventures in foreclosure law. And we gave him a chance to write it, and we thought, well, if he writes it well. And then we spent about ten days fact-checking, and everything held up. And so, we published it. So I think that there’s a room there for the less experienced journalist, but mostly I want to hear from the people that know how to get at the facts, that know where the bodies are buried, that know inside and out of every city hall and government bureaucracy and tell me what I need to know. That’s what I go for - that, that newspaper for. So -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Let's talk about the traditional role of the newspaper in a community. At least historically it’s come out every day. What you've produced is something that one could take weeks to read all the way through.

DAVE EGGERS: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you've said that that was intended to be a kind of idealized Sunday newspaper?

DAVE EGGERS: A little bit. I mean, it’s a concept car. It’s sort of saying here’s all the things that the form can do. And we never said this is a daily newspaper. We said this is a -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: No, of course.

DAVE EGGERS: - celebration of the print form.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You think that daily is still the best way to go?

DAVE EGGERS: For me, I don't know what I would do if I didn't have two, three daily papers a day to read. I don't want to read online. I don't want to wake up and look at a screen. I feel like, you know, as a society, we try to put everything on that same goddamn screen. And pretty soon we're going to be eating on the screen or like -

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER] - making love through the screen. It’s just sort of like why does everything have to be on a screen? You know, there’s been some study that was quoted in one of our panels that said that even how we read our blood pressure is different when we read on print than when we read online. I think that it’s too exciting and distracting online. There’s always some button that wants you to click to cat porn, you know, online.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER] It’s just like you’re trying to read some article and it’s flashing and it’s telling you to go somewhere else. [LAUGHS] I like the curatorial, the calmness, the authority of a daily paper. But I do think that it’s a time to make the paper form more robust and more surprising and beautiful and expansive. People still want to read long form literary journals and nonfiction, etc., and so why can't the print medium do that and be that home and leave the Internet to do the more quick thinking and quick reacting things?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I would really love to ask any of the leaders of the papers in here what Panorama suggests for you. What can you take away from it? Is it relevant to the work that you do? Go ahead.

MIKE WILSON: I'm Mike Wilson. I'm from the St. Petersburg Times in Florida. To answer your question, Brooke, about whether we thought it was relevant, in my newsroom, absolutely. And The St. Pete Times has a tradition of doing long form narrative journalism. I took it as a tribute, but also a challenge to do more and do it better. I thought it gave us a chance to look at what news is a little differently. You had a page of news items that had happened, say, in the last month before publication, it was just done in a really delightful way.

DAVE EGGERS: Yeah.

MIKE WILSON: And I thought that there was some instruction in that for us in what we put in print but also in the sense what we put on the Web. There are interesting things that happen that are small things but meaningful.

DIANA MARRERO: Hi, I'm Diana Marrero with The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. I'm curious. You said you read two or three papers a day. What are they, and what’s your favorite newspaper?

DAVE EGGERS: Well, I read The Chronicle and The New York Times, for sure, every day, then The Examiner, which is also in San Francisco, that I get free on my block, so those three papers every day. And then if I'm anywhere that the USA Today is, I'll read that, and I like the Wall Street Journal a lot. And then I get The Guardian in London sent to me bulk once a month. The Daily Zaman, we now subscribe to that. That’s in English and Turkish every day out of Istanbul. Can you believe it? I'm a fan of the form. You know, I always will be. I'm just in awe of what gets done every day. Having gone through it this time, I was a hundred times more in awe of what happens every day. And so, I sort of am personally relying upon the survival of the form, at least until I'm in the grave. Then after that, who knows? Thanks for letting me be here, everybody.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you so much.

[APPLAUSE]