Defining Moments

BROOKE GLADSTONE: September 18th is the tercentenary, the 300th birthday, that is, of Samuel Johnson, whose Dictionary of the English Language set the standard and the format for centuries of dictionaries. His format - with head words, etymologies, sample sentences – remains unchallenged. But his standard, what dictionaries stand for, has been undergoing a slow but inexorable evolution, as OTM’s own Mike Vuolo reports.

MIKE VUOLO: In 1754, the Earl of Chesterfield anxiously wrote that English was in a state of anarchy.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: And all of a sudden that anxiety just dissipates.

MIKE VUOLO: Geoffrey Nunberg is a linguist at the University of California at Berkeley.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: Johnson has showed that all of the flux of the language can be reduced to rule and put within the covers of a book, and the English language is settled forever. Now, of course, the English language was not settled forever.

MIKE VUOLO: Enter Noah Webster, born in a British colony called Connecticut, just a few years after Johnson’s dictionary was published. In 1789, the year America held its first Presidential election, Webster wrote, “Our honor requires us to have a system of our own in language as well as government.” Geoff Nunberg.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: We've broken away in politics. We're breaking away in culture. Why should we speak the same language? And Jefferson and Adams and Webster were only some of the figures at the time who thought, no, we would speak American or Federal.

MIKE VUOLO: Published in the late 1820s, Webster’s dictionary introduced thousands of new America words, plus new American definitions of words, and it changed the way we spell – o-r instead of o-u-r, e-r instead of r-e.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: Webster's dictionary was very much an attempt to replace Johnson's dictionary, at least in the American context, where a dictionary that would reflect the values of this new democratic society that had emerged on the other side of the Atlantic.

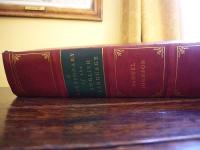

MIKE VUOLO: Fittingly, Webster called his book An American Dictionary of the English Language. Its only true descendents today are the Merriam-Webster dictionaries, the Merriams being two brothers who got the publishing rights after Webster died. The company’s 1934 landmark New International Dictionary, Second Edition, was 17 pounds with more than 600,000 entries. It was, and is, the largest single volume dictionary of English and was deemed not only authoritative but the authority, period.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: That dictionary seemed to crystallize the language of public discourse as it should be.

MIKE VUOLO: So how do you follow an act like Webster’s Second? With Webster’s Third, published 27 years later, edited by the scholarly and degree-laden Philip Gove, who, unlike his predecessors was a linguistic egalitarian. National Endowment for the Humanities editor David Skinner, who is working on a book about the Third, says that even pronunciations are created equal under Gove. Take, for example, err – e-r-r.

DAVID SKINNER: If you look up the word in Webster’s Third, you get at least five pronunciations. They are “err,” “air,” like the air we breathe, “er” – the very old-fashioned one – "arrr" [?], which I don't recall hearing myself, and the more British “eh,” [?] without even an R. So if you want to know how to say this word, “e-r-r,” you’re in for some very hard work when you open Webster's Third. Another example, this one with regard to spelling, is the term “memento.” Memento is spelled m-e-m-e-n-t-o, but some people misspell it. They write “m-o-m-e-n-t-o,” like moment-o. The editors of Webster's Third included this as a legitimate variant, but I think most people would tell you that’s just a misspelling.

MIKE VUOLO: It’s just wrong.

DAVID SKINNER: It’s just wrong.

MIKE VUOLO: In his zeal to describe words as people used them, Gove sometimes veered off into the insulting. One of his definitions for the word “Jew,” for example, is, quote, “a person believed to drive a hard bargain.” In his zeal to define words for a popular audience, Gove sometimes veered off into the absurd. Take the definition for the word “door.” I asked some people on the street to define it for me.

[STREET SOUNDS]

WOMAN: The point in space that represents the threshold between two separate areas.

MAN: Uhh, [SIGHS] part of a wall that moves, allowing you access to the other side of the wall?

WOMAN: Something that keeps people out.

MAN: Oh, goodness. How much time do you have? [LAUGHS] MIKE VUOLO: In the New York Public Library, Assistant Director of Reference Services, Matthew Sheehy, thumbed through Webster's Third in the main reading room, looking for “door.”

MATTHEW SHEEHY: It’s a big book. “A moveable piece of firm material or a structure supported usually along one side and swinging on pivots or hinges, sliding along a groove, rolling up or down, revolving as one of four leaves or folding like an accordion by means of which an opening may be closed or kept open for passage into or out of a building, room or other covered enclosure, or a car, airplane, elevator or other vehicle.” And that’s just the first definition of the word. It goes on.

MIKE VUOLO: Who exactly is that definition for?

MATTHEW SHEEHY: I would say that definition is for a Martian, I mean, someone who’s never seen a door ever and has no concept of what a door is. The best thing about it, of course, is there’s an illustration next to it in case you need it to visualize what a door is.

MIKE VUOLO: On the other hand, Gove sometimes gave too little information. He did away with many judgmental labels, like “improper,” “erroneous” and “colloquial,” and he withheld judgment in other ways, too. David Skinner.

DAVID SKINNER: Webster's Third offered a more complete set of curse words. It introduced, for instance, [BLEEP], [BLEEP] and [BLEEP]. Webster’s Second gave a very literal definition for homosexual, attracted to someone of the same sex. If you look it up in Webster's Third, it says “homosexual” is a normal stage in male adolescent development. That’s a very different kind of dictionary.

MIKE VUOLO: But it was a very different four-letter word that caused perhaps the loudest outcry. The linguist Geoffrey Nunberg:

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: Where Gove went off the rails, as far as his critics were concerned, was in failing to condemn words like “ain't,” and in that sense the dictionary represented, in the views of many of its critics, an assault on all that was important about culture – “those patient and dedicated saboteurs in Springfield, Massachusetts,” as Wilson Follett described the editors of Webster's Third. It was a huge brouhaha.

MIKE VUOLO: In 1961, when Webster's Third was published, Philip Gove was the lexicographical Antichrist.

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: There were cartoons in The New Yorker – a man coming into the reception area of Merriam-Webster and the receptionist saying, Mr. Gove ain't in; Nero Wolfe, in one of the Nero Wolfe detective stories, tearing apart a copy of Webster's Third and feeding the pages to the flames in his fireplace, saying, contact is not a verb in this house.

MIKE VUOLO: The Washington Post printed an editorial under the headline, “Keep your old Webster’s. The New York Times Book Review called the Third “a gigantic flop.” The Detroit Free Press said it was “cheap and corrupt.” Quote, “It is not a dictionary as Samuel Johnson or Noah Webster conceived of one. It is a catalog.”

GEOFFREY NUNBERG: The business of a dictionary is to really do two things. It’s to describe usage. It’s to say, for example, the adverb “literally” has been used since the early 19th century at least in a sense that means figuratively. Thackeray wrote, “I literally blazed with wit.” At the same time – and this is something else dictionaries have to say – there are people who are driven up a wall by this.

ERIN McKEAN: Anybody who expects language to be logical should go back and think again.

MIKE VUOLO: Erin McKean is former editor of The New Oxford American Dictionary.

ERIN McKEAN: The words that we have have grown up organically. They are not concrete blocks. They're river stones.

MIKE VUOLO: To the persnickety language police types – McKean calls them “peevologists” – one big jagged river stone of a word is “irregardless.”

ERIN McKEAN: I would defy any peevologist to show me an example where someone got completely the wrong idea from the use of the word “irregardless.” Now, that said, do I think everybody should go out and use the word “irregardless?” And I say no, because it’s what’s called a “skunked term,” where there are so many people who are upset about this word that we have to kind of leave it alone until the smell wears off.

MIKE VUOLO: Smelly or not, it’s in Philip Gove’s Webster's Third, and it is certainly in Erin McKean’s own online dictionary, Wordnik. For any given entry, Wordnik contains recent examples from print and the Internet and real-time examples from a Twitter feed. It compiles statistics, like frequency of use dating back to 1800, and provides a place for users to leave notes that may be helpful to others. McKean calls Wordnik the ultimate descriptive dictionary. She wants to document all words that are used, however fleeting, however novel, however made up.

ERIN McKEAN: Yesterday [LAUGHS] I was talking with some of the people I work with and I said, okay, well, that makes the problem much more breakdownable. And they looked up at me and they said, breakdownable? I said, you understood it, didn't you? [LAUGHS] And we went and looked it up, and, you know, we didn't really have any data for it. But it existed. I mean, the minute I said it, they understood me, and we should record all of that.

MIKE VUOLO: Should we? Really? I remembered a sentence I read last year in The Wall Street Journal Online, September 17th, 2008 by financial journalist David Gaffen. “For all of the consternation surrounding the craptacular performance of the financials, it is worth knowing…” Wait, wait a minute. Let's hear that again. “- surrounding the craptacular performance of the financials…” Maybe like me, you were confused by “craptacular.” I called David Gaffen, who now works for Reuters.

DAVID GAFFEN: I think it is meant to meld together the words “crap” and “spectacular,” so it is an amazingly terrific train wreck of a performance of something. And that’s kind of what was going on with the financial stocks at the time. They were spectacularly awful. It’s in Wordnik. It’s in The Wall Street Journal, albeit online. How about Webster’s? I called Peter Sokolowski, Merriam-Webster’s editor-at-large, and asked him to define “craptacular.”

PETER SOKOLOWSKI: [LAUGHS] You need to use it in a sentence [LAUGHS], just like a spelling be, because context is everything. But we have our open source dictionaries free online, and I bet it’s there and I bet it has some kind of a nickel definition.

MIKE VUOLO: Okay, let me check that out.

PETER SOKOLOWSKI: Craptacular, craptacular.

[SOUND OF TYPING]

MIKE VUOLO: Craptacular. PETER SOKOLOWSKI: There it is. MIKE VUOLO: “Spectacular crap.”

[LAUGHTER] Something that is rendered shocking or fascinating by its low quality or poor condition. The rotten old abandoned amusement park was a craptacular place to spend the afternoon.

PETER SOKOLOWKSKI: Now, that’s a useful entry.

MIKE VUOLO: So it was in Merriam-Webster after all, written not by a lexicographer but by a citizen wordsmith in its online open source dictionary. As for the unabridged Webster's Third, well, it’s been nearly 50 years since Philip Gove was headline news, and now his dictionary is the authority, perched on a lectern outside the reading room at the Library of Congress, although a fourth edition is reportedly in the works, and it when it does come out, some guardians of the English language will declare it the death of standards and the ruination of all that was holy in our language.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER] And the rest of us will shake our heads and say, ain't that just craptacular? For On the Media, I'm Mike Vuolo.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That's it for this week's show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Mike Vuolo, Mark Phillips, Nazanin Rafsanjani, Michael Bernstein and P.J. Vogt, with more help from James Hawver and Dan Mauzy, and edited by me. We had technical direction from Jennifer Munson and more engineering help from Zach Marsh.

Katya Rogers is our senior producer and John Keefe our executive producer. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. This is On the Media from WNYC. Bob Garfield will be back next week. I'm Brooke Gladstone.