9/11 And Films

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We don't usually take notice of September 11th anniversaries, not having much to add. But a new book just came in that explores how Hollywood has processed that terrible day in the eight years since, so we thought we'd take a minute to remember. On that day, people running from the wreckage or watching on TV all used a common vocabulary to describe what they'd seen.

BROOKE GLADSTONE [2001]: Talk to me about what it was like. Were you able to get out? Was it –

[OVERTALK]

MAN: Well, it was like it was a World War II war movie. I mean, there was just debris everywhere.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Whether science fiction or horror, whatever the genre, it was like a movie. We've enjoyed so many disasters from the darkness of a theater we never imagined one could ever burst forth into the light of a late summer morning. Did the reality change our view of cinematic explosions? For perspective, in September of 2001 I asked Variety columnist Tim Gray about the audience response to an explosive hit back in 1996.

[EXPLOSION SOUNDS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When you saw Independence Day —

TIM GRAY: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: when the White House blew up

TIM GRAY: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: did your audience cheer?

TIM GRAY: Yeah, yeah, it was, like, whoa! I mean, up until a week ago you would see a big building exploding and think, cool, dude! Wow! Terrorists were always cartoon creatures that were just there to be eventually foiled by the heroes. And whenever the terrorists created their mayhem, it was always a room full of anonymous people who got blown up. I can't imagine anybody watching a movie now filled with pyrotechnics, with the same kind of innocence we had before, you know. Every country in Europe went through World War II where they went through horrible experiences. And America hasn't been under fire, and suddenly we're under fire here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: European cinema is not known for dazzlingly rendered disasters. Gray suggests that American movie mayhem is popular there partly because the chaos happens here. They can savor it and shrug it off, just as we have. But there was no shrugging off the TV footage seen around the world on 9/11. British novelist, Ian McEwan.

IAN McEWAN: Nothing Hollywood ever dreamed up prepared us for a minute for any of this, because we know the difference. We're not stupid. Even before the towers crumbled and we were simply watching through telephoto lens we knew, we could imagine the hell inside as people ran for their lives, that we knew the elevators would not be working, we knew the pandemonium that must be going on in these stairwells with people trying to get down. Also, there are no heroes, not at that stage. There are only victims. And that's unlike Hollywood. Those Hollywood dramas seem piffling alongside this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we wondered what movies people were watching for perspective, or solace. When we called a video store on New York’s Upper East Side, the manager said that romantic comedies were flying out of the place. No disaster films, he said, except one — The Siege, made in 1998, an action film with terrorists, and a message.

[CLIP]:

DENZEL WASHINGTON AS ANTHONY HUBBARD: What if what they really want what if they don't even want the sheikh?! Have you considered that? Huh? What if what they really want is for us to herd children into stadiums like we're doing and put soldiers on the street and, and have Americans looking over their shoulders, bend the law, shred the Constitution just a little bit? Because if we torture him, General, we do that, and everything that we have bled and fought and died for is over, and they've won.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: For eight years, Hollywood has been processing the 9/11 attacks. Stephen Prince, a professor of cinema at Virginia Tech, has reflected on their impact on the big screen in his new book, Firestorm: American Film in the Age of Terrorism. He says that one constant in the films before and after the event is the reaction of celluloid crowds to big bangs.

STEPHEN PRINCE: One of the things that always happens in big disaster movies is that people panic and stampede and scream and yell at one another, and that’s what we see in Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds.

[CLIP]:

[CHAOTIC SOUNDS]

MAN: There is plenty of room! There’s room for hundreds more!

[END CLIP] It was consciously meant to be a reply to the 9/11 event. And what all that misses is the remarkable spirit of cooperation that prevailed at the World Trade Center. This was the great challenge that feature filmmakers confronted, how to create stories that would capture the truth of these attacks.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In Spielberg’s film The Terminal, Tom Hanks plays a guy from a mythical country whose country basically goes into upheaval by the time he lands in the airport. It is no longer recognized by the United States. He’s a man without a country. He has to live in the airport. What does that say about us, do you think, post 9/11?

STEPHEN PRINCE: The Terminal is a wonderful and overlooked film. It’s a film about America being closed -

[CLIP]:

BARRY SHABAKA HENLEY AS THURMAN: Mr. Navorski, I need you to look at me. Beyond those doors is American soil. Mr. Dixon wants to make it very clear to you that you are not to enter through those doors. You are not to leave this building. America is closed.

[END CLIP]

STEPHEN PRINCE: about a country that, as the movie depicts, is full of immigrants who have brought so much, and yet the policy of cracking down on immigration after the attacks denied the best attributes of the country.

[CLIP]:

TOM HANKS AS VIKTOR NAVORSKI: Well, what I do?

BARRY SHABAKA HENLEY AS THURMAN: There’s only one thing you can do here, Mr. Navorski, shop!

[BELL SOUNDS] [END CLIP]

STEPHEN PRINCE: The villain of the picture is a Homeland Security official, and the Homeland Security logo appears prominently at several points in the film.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So talk about now the relevance of his film, Munich.

STEPHEN PRINCE: Munich is a movie that is not a crowd pleaser like these others; Munich, of course, being a film about the 1972 massacre of the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

RANA WERBIN AS ISRAELI TELEVISION ANCHOR: People are weeping, tearing their clothes. The funerals, which will be held tomorrow in Jerusalem, are expected to draw tens of thousands of mourners. These are the names of the members of the Israeli team at the

[END CLIP]

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

STEPHEN PRINCE: We have a very sustained, serious attempt to think about the morality of both terrorist violence on the one hand and how a state responds to that on the other. What makes the film so striking is the empathy that Spielberg shows for both sides in that struggle, and this gave the film a measure of controversy when it came out. The ending of the movie is quite haunting. In the last seconds of the film, the camera pans over the Manhattan skyline to reveal the World Trade Center, and that’s our closing image.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the aftermath of 9/11, some of the feature films that dealt with it were actually faithful depictions of the events that occurred. I'm thinking of a film like United 93 that was directed by Paul Greengrass, and The World Trade Center, directed by Oliver Stone.

STEPHEN PRINCE: Those two movies are remarkably different from one another. World Trade Center is based on the experiences of two Port Authority policemen who were trapped in the rubble of the collapsing towers. It treats the attacks as mostly an off screen event. The many horrifying things that occurred that day have little to no screen presence. In this respect, United 93 is interestingly different. Greengrass in that film does show the strike on the second tower, and he presents in really harrowing detail, the encounter on the titular flight between the hijackers and the passengers.

[CLIP]:

CHRISTIAN CLEMENSON AS TOM BURNETT: We’re going to take back the airplane.

ACTRESS AS DEENA BURNETT, ON PHONE: What? No, no, no. Just sit down and be still, be quiet. Don't draw attention to yourself.

CHRISTIAN CLEMENSON AS TOM BURNETT: Deena, they're going to take us into the ground. We've got to do something. It’s up to us to do it. No one else can.

ACTRESS AS DEENA BURNETT, ON PHONE: [CRYING] What do you want me to do?

CHRISTIAN CLEMENSON AS TOM BURNETT: Pray, Deena.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

STEPHEN PRINCE: This was the great challenge that feature filmmakers confronted, how to create stories that would capture the truth of these attacks.

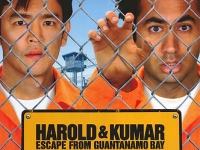

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You argue, though, that the most successful formula for a post 9/11 box office success is to fit the terror films into genre movies. The genre gets the audience in their seats and the terror references just add food for thought. You give examples that basically range from The Dark Knight to Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantanamo Bay.

STEPHEN PRINCE: Yes, and isn't this the opposite of what was initially claimed after 9-1-1 —

[BROOKE LAUGHS] — that Hollywood would need to find new formats in order to portray the events? What happened is that the industry kept all of its conventions and formats and simply found ways of absorbing this material into them. So you can have a movie like Iron Man where he goes to Afghanistan and gets mixed up with thugs and terrorists, but there are no Taliban and no Islamists anywhere to be found. The Dark Knight is a film where you have the Joker as an anarchist intent on sowing chaos in Gotham City.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP AND UNDER]:

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

HEATH LEDGER AS THE JOKER: Introduce a little anarchy. Upset the established order and everything becomes chaos. I’m an agent of chaos. Oh, and you know the thing about chaos? It’s fair.

[END CLIP]

STEPHEN PRINCE: But he’s not somebody that has a political program for acting the way he does. Bin Laden, by contrast, has reasons that he has specified at length. So all of this packaging is a way of addressing the world that we know we inhabit but not in ways that threaten the entertainment value of big franchise pictures.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How does Harold and Kumar fit into this?

STEPHEN PRINCE: Harold and Kumar is one of the very few films that has used humor to probe the post 9-1-1 world.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP AND UNDER]:

JOHN CHO AS HAROLD LEE: Do we have the right to make a phone call?

ROB CORDDRY AS RON FOX: Oh, oh, yeah. Oh, yeah, I'm sorry. You want rights now. You want freedoms right now. Is it time? Is it freedom o’clock? [LAUGHS] Guess what?

KAL PENN AS KUMAR PATEL: What?

ROB CORDDRY AS RON FOX: Where you guys are going, they have never even heard of rights.

[END CLIP]

STEPHEN PRINCE: There’s a small sequence in the film where they're captured at Guantanamo on suspicion of being terrorists, and a Homeland Security official interrogates them and wipes his rear with the Bill of Rights. That’s about as politically pointed as the humor in the film gets.

[CLIP/TEARING SOUND]:

DAVID KRUMHOLTZ AS GOLDSTEIN: Don’t you wipe?

ROB CORDDRY AS RON FOX: Don’t ask questions you don’t want the answer to, buddy.

[END CLIP]

STEPHEN PRINCE: The movies have been working very hard to persuade us that we're in good hands, that the security forces are a jump ahead of the terrorists and that they're going to find out about the plots in the nick of time. We know the story of 9/11 was very different. It was a story of chaos and breakdown in the chain of command. This is something our films have not shown us very honestly. Instead, they acknowledge the kind of world that we all know we now live in, and they make it habitable by reassuring us that in the end, everything is going to be okay.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: All right, thank you very much.

STEPHEN PRINCE: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Stephen Prince is a professor of cinema at Virginia Tech and author of Firestorm: American Film in the Age of Terrorism.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week's show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Mike Vuolo, Mark Phillips, Nazanin Rafsanjani, Michael Bernstein and P.J. Vogt, with more help from Dan Mauzy and James Hawver and edited — by Brooke. We had technical direction from Jennifer Munson and more engineering help from Zach Marsh.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our senior producer and John Keefe our executive producer. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. You can listen to the program and find transcripts at Onthemedia.org. You can also post comments there, or email us at Onthemedia@wnyc.org. This is On the Media from WNYC. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I'm Bob Garfield.