Pulp Fictions

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Eric Burns is the author of All the News Unfit to Print, a catalog of journalistic misdeeds dating back to, well, before the American Revolution. Not all the malefactors in his compendium are American, but one thing they do have in common is their flawed humanity.

ERIC BURNS: Journalists lie or misbehave for a variety of reasons. And in Samuel Johnson’s case, it was on the one hand laziness – he just didn't like to get out of his equivalent of a bathrobe – and he was also quite embarrassed about his appearance. He was ungainly in physique. He had a pockmarked face. And so, when he got a job with a magazine called Gentleman’s Quarterly to cover Parliament, which he did every day for more than two years, he showed up at Parliament – once.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] And yet he managed to write verbatim the speeches of the Parliamentarians on the floor - hence his regret.

ERIC BURNS: Basically, Brooke, the way it worked was that Johnson knew the members of the House of Commons, he knew how they felt about various issues, he knew who was scheduled to speak and on what issue on a given day, and so he just wrote the dialog or the monologues for them, which raises the question, I think, didn't they ever complain? And the answer is, no, they never complained because Samuel Johnson was [LAUGHING] so much more eloquent than they that they would rather have Johnson’s paraphrase of their sentiments appear in The Gentleman’s magazine than they would their own words. As a result, we do not know to this day exactly what went on in Parliament between, I think, 1720 and early 1723.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And we'll always have the lasting impression that that was a particularly eloquent school of Parliamentarians.

ERIC BURNS: [LAUGHS]

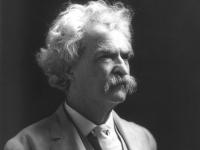

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, the biggest, best and the worst, I think, liar in your book is the unrepentant, incorrigible Samuel Clemens, who lied for laughs -

ERIC BURNS: Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - he lied for a cause, and he lied for his own enrichment.

ERIC BURNS: He lied as well, I think, Brooke, because he just didn't care that much about journalism. He got bored so he made up, for instance, an ossified – which is to say a petrified man in the desert, who never existed. Clemens just thought it would be a good idea to write about one. He had some strong feelings about those who speculated in stocks and wrote about a terribly bloody massacre in which a speculator had had his scalp cut off and bled to death. Well, that never happened, either. And Clemens defended this on the notion that as the Bible tells parables to illustrate a point, I am, in effect, telling a parable to illustrate a point.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you reserve your own greatest disgust for the time that he basically – well, go ahead and say it.

ERIC BURNS: Well, he sold out in a manner that most journalists before and since have never sold out. He was looking at labor and management struggles – very much a liberal, very much on the side of the laborer, the working man. And suddenly when he was living in Buffalo and was the editorial page editor of Buffalo’s leading newspaper, he took management’s side and excoriated the working men for wanting more than they did. Not only that, but next to his editorial he published another editorial from a New York City paper – this, as I said, was Buffalo – which supported his position. And people were astonished, wondering how he could have changed his mind to the extent that he did. Well, as it happened, he was engaged to be married to the -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mine owner’s daughter.

ERIC BURNS: To the mine owner’s daughter. He sold out his point of view because he didn't want his fiancée to be upset with him, or his future father-in-law.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, he wrote about what he did, and this is why I called him unrepentant. Will you read what he said about lying and the press?

ERIC BURNS: “The wise thing is for us diligently to train ourselves to lie thoughtfully, judiciously, to lie firmly, frankly, squarely, with head erect, not haltingly, tortuously, with pusillanimous mien, as being ashamed of our high calling.” My concluding sentence to that chapter is there is no reason to think he was kidding.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Let's take a moment for William Randolph Hearst. We had his biographer and an historian of so-called “yellow journalism” on the show just a few weeks ago, and both said that Hearst had been given a bad rap, that his paper produced some of history’s best reporting and that his opposition to Spain’s merciless domination of Cuba, which led to the Spanish-American War, was heartfelt and genuine.

ERIC BURNS: Well, I concede in All the News Unfit to Print that one of Hearst’s motivations was that he felt a genuine sympathy for the way the Cuban people were being mistreated by the Spaniards. I also say that another motivation was circulation. His paper was The New York Journal. He was in a circulation war at the time with Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. When the war finally started, The New York Journal, Hearst’s paper, ran a banner at the top for two days which said, “How do you like The Journal’s war?” There were so many complaints that he had to drop that. But if he were sincerely concerned primarily with the fate of the Cubans, I don't think he would have been bragging about having started a war.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Walter Duranty, the New York Times reporter in Moscow in the '20s and '30s, won a Pulitzer in 1932, one that even The Times would be glad if the Pulitzer board would take it back. But the board has refused.

ERIC BURNS: Well, there’s a sense in which he deserved the Pulitzer because he won it for a 13-part series on what the Soviet Union was like under Stalin, and there was a lot of information in it that Americans didn't know. Unfortunately, there was something that wasn't in it, and that was what has later been considered officially by government bodies an act of genocide that Stalin was perpetrating by having created a famine in the province of Ukraine. Stalin had a five-year program, and the goal was in five years for the Soviet Union to be technologically and industrially the equal of the United States. One of the ways that he had to do that was that he had to make sure his workers in the more industrialized provinces had enough to eat, had enough energy to work their endless shifts. And so he had soldiers steal grain, steal foodstuffs from the relatively backward province of Ukraine. The result was that millions of people died by a famine that was manmade. And Walter Duranty, because he was a Stalinist, because he was so loved by Stalin for his reporting that he was the only Western reporter ever to interview Stalin, Walter Duranty refused to report on this because it went against his political views. And when he finally – because so many other newspapers in Great Britain and the United States were reporting on it – when he finally turned his attention to it, the first thing he says was, reports of the famine are bunk. It was, Brooke, in many ways one of the most disreputable acts ever performed by a journalist. Part of the reason that there was such a powerful anti-Communist effort in this country in the '50s – Joe McCarthy led it – was that there was also powerful sentiment in this country for Stalin, that Communism was the answer to such excesses of capitalism as the Great Depression. And part of the reason so many Americans believed in Communism as the answer to capitalism’s excesses was that people like Walter Duranty did not report at the start the massive failures of Stalin’s program.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jumping off of Duranty, you have a fairly long discussion of what you call “lies of omission.”

ERIC BURNS: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Rarely do they achieve the breadth and horror of what Duranty left out of his stories. In fact, some more fastidious news consumers might wish that reporters would withhold more of the details of the sexual peccadilloes of our leaders, as they did generations earlier.

ERIC BURNS: Well, there were two topics that in the middle of the 20th century were simply not reported on when it came to covering government officials – their sex lives outside of marriage and their drinking habits. Again, The New York Times comes to mind. I've forgotten the reporter’s name, but there was a very close vote on a very important issue one day, and a senator had to be carried into the chamber because he was so hung over from the night before.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What era was this?

ERIC BURNS: This was in the '50s. And the woman who was covering this story for The New York Times said this was part of the story. There’s a chance that this man might not have been able to get to the chambers to cast his vote, and if he hadn't – it was a tie vote – the course of this legislation would have changed. I am not – this reporter said to her editor – I'm not trying to write something prurient. I'm trying to tell the whole story of how this bill was passed. Sex lives were also thought to be off limits, and, in fact, Wendell Willkie, who challenged FDR for the presidency once, was so well known to have a mistress in New York that he decided to have a press conference once in her apartment. Now, one of his advisors talked him out of it, but reporters had in their whatever the predecessor of a Rolodex was the phone number of Willkie’s mistress. And when they needed to reach him for a quick quote, the first call went to the mistress, the second call went to his home. None of that ever appeared in a publication.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Finally, many media watchers and old-time practitioners lament that in this age of blogs and Twitter and broken business models and blah, blah, blah, that journalistic ethics are being eroded so much that it imperils our very republic. But your book makes the case that there never really was a golden age, and yet the republic endures.

ERIC BURNS: There never was a golden age. From the very beginnings of journalism we've had people who, because of ideological bias, who, because of laziness, who, because of a lack of respect for the profession, did not care enough about their story to make sure that it was accurate. One of the reasons that the republic is not imperiled by irresponsible journalism is that we have had such an explosion in journalistic outlets - yes, we're losing newspapers but we're certainly gaining on the Internet – that irresponsible journalism is going to be detected today more easily than it ever was before. So we have two things going in contrary directions at once. Because we have so many journalistic outlets, the odds are greater that we'll have erroneous coverage. Because we have so many journalistic outlets, the odds are greater that some of that coverage will point out the errors in some of the other coverage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So not the collapse of civilization.

ERIC BURNS: No. Not even the collapse of journalism.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

ERIC BURNS: Thank you for having me, Brooke.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Eric Burns is the author of the new book All the News Unfit to Print.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week's show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Mike Vuolo, Mark Phillips, Nazanin Rafsanjani, Michael Bernstein and P.J. Vogt, with more help from Kara Gionfriddo, Ethan Chiel and Andy Lanset, and edited – by Brooke. We had technical direction from Jennifer Munson and more engineering help from Zach Marsh. Our webmaster is Amy Pearl.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our senior producer and John Keefe our executive producer. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. This is On the Media from WNYC. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I'm Bob Garfield.