Transcript

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

From WNYC in New York, this is NPR's On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD:

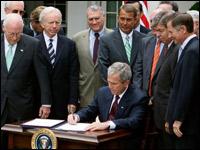

And I'm Bob Garfield. After two and a half years of furious debate following the publication of a New York Times story about the government’s secret warrantless wiretapping program, on Thursday, the President signed the new Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH:

Today I'm pleased to sign landmark legislation that is vital to the security of our people. The bill will allow our intelligence professionals to quickly and effectively monitor the communications of terrorists abroad while respecting the liberties of Americans here at home.

BOB GARFIELD:

The new law still requires the government to obtain warrants to eavesdrop on U.S. citizens but permits it to listen in on the phone calls of foreign nationals outside the country without warrants, even if they are speaking to people in the U.S.

It grants retroactive immunity to the telecom companies that assisted in the earlier eavesdropping and effectively closes down dozens of lawsuits challenging the program’s legality. It also expands the government’s power to invoke emergency wiretapping procedures.

Despite the vehement protests of liberal Democrats and civil liberties advocates, it easily passed both in the House, 293 to 129, and the Senate, 69 to 28. Tim Starks has been following the bill for Congressional Quarterly. Tim, welcome to the show.

TIM STARKS:

Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD:

Now, let me see if I understand this correctly. If I am suspected of, let's say, participation in organized crime, the federal government or the local police can get a wiretap on me but they have to go to a court.

Under the 1978 version of FISA, the federal government had the option of going to a secret court in order to get a court order for a wiretap. But, as The New York Times revealed, in the last few years the administration has been skipping the court process altogether and simply getting the wiretaps under a presidential finding that does not involve the judiciary at all. Does the new version of FISA etch that ability into concrete?

TIM STARKS:

That is essentially what it does. Now, keep in mind that there is something unique about the way this law is structured in that it is most focused on who the government is targeting. So if you’re in the United States and they decide that they would like to go after you and monitor your communications as the target of interest, then they do still need a warrant.

But if the government declares that someone overseas is its target, whether that person is communicating with someone in the United States or not, the government does not need a warrant. The courts are effectively out of that deal. The people in the administration are the people who end up deciding who they can conduct surveillance of in those circumstances, with no oversight from the court.

BOB GARFIELD:

Now, there were two issues here, as I understand it. One was whether in the name of national security, the President should have such wide berth to do the kind of snooping that had long since been illegal in this country, and the second, whether the phone companies who cooperated with these warrantless searches were liable in court for either prosecution or litigation based on helping the administration violate individual privacy.

To protect them, this law actually gives them immunity from any kind of suit. Why was this an issue?

TIM STARKS:

There were a few reasons. One is that they argued that if the government came to them with another request to help conduct spying, those phone companies would be more concerned about their exposure to lawsuits than to the sensitive national security interests of the country. That was one reason.

Another reason that the critics focus on is that they didn't want anyone to find out about how their program ran.

BOB GARFIELD:

In other words, in defending a suit against them, the phone companies in court would reveal the means by which the government got all of this data.

TIM STARKS:

Right, exactly. This was something they hoped to avoid for, you know, the reasons that I mentioned — either to defend the security of the program or, in the eyes of critics, to cover up their own lawbreaking.

BOB GARFIELD:

Now, in advance of this week’s vote, The New York Times and many other newspapers, with a big thumbs up from the ACLU, editorialized against this bill as making the public too vulnerable to government excess. Yet the bill passed by a very large margin in Congress. Why did this big controversy end in such a lopsided vote?

TIM STARKS:

Well, there were a number of factors that went into that. The Senate had always been pretty amenable to the administration’s position on all this. The House had really been holding out.

What ended up happening was, over time, two things. One, there were some surveillance orders that were approved under a temporary spying law that the President and Congress had agreed to, late last summer and those surveillance orders were going to start expiring beginning in August.

The other thing that happened was that there was another group of moderate to conservative Democrats in the House who had been really agitating for something to get done. They had different political pressures than some of the more liberal members in the House because their constituents maybe would be inclined to vote for a Republican who was in favor of this, or so they feared.

So as they began to agitate, the House Democratic leadership got worried that if they didn't step in and try to come up with something that was a little bit better than what the administration wanted, that they were going to get what the administration wanted jammed down their throats whether they liked it or not.

Now, another factor that probably played into this was a general concern from Democrats, because typically Republicans go on the attack on national security and say that Democrats are weak on that. And this could have played into that.

BOB GARFIELD:

Barack Obama voted in the Senate for this new law, having much criticized an earlier version of it. This has raised a lot of eyebrows. Is he trying to get, you know, some national security bona fides for the upcoming election?

TIM STARKS:

It certainly looks that way. What’s interesting about all that is that the issue of immunity is not particularly popular with people because, frankly, a lot of people don't like their phone companies and are not really looking to bail them out or help them in any way.

And on the issue of how the spying would be conducted, it was extremely complicated, and it was also something that people weren't really sure about one way or the other, about what they wanted.

BOB GARFIELD:

Okay, Tim. Thank you so much.

TIM STARKS:

You’re welcome.

BOB GARFIELD:

Tim Starks writes about the intelligence community for Congressional Quarterly.