Transcript

BOB GARFIELD:

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

There are between six and seven-thousand languages spoken around the world, and nearly half of them face extinction. About once every two weeks, a language dies out in remote and sometimes not so remote places. Here in the U.S., in the Pacific Northwest and in Southwest Oklahoma, indigenous languages face rapid extinction.

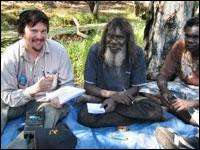

That's where linguist Greg Anderson comes in. He's director of The Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. He circles the globe trying to record the last remnants of dying tongues.

Greg says when a language goes extinct it takes entire means of expression, bodies of knowledge, ancient narratives, even entire cultures along with it.

GREG ANDERSON:

It erases the vast majority of the stored knowledge that that group of people has accrued, so their own history, knowledge that they've accrued about interacting with their ecosystem, whether it's plant management, animal resource management, you know, fishing techniques, whatever it is, all of this basically [LAUGHS] is being lost because this knowledge is stored in languages which aren't written, are threatened and, you know, probably never will be written.

BOB GARFIELD:

So somewhere in Central South America, in some mountain village, the cure for some disease could be harbored in the language of a tribe and could disappear along with that language.

GREG ANDERSON:

Absolutely. In fact, the use of quinine against malaria — there's this group that had this knowledge for a long time before Westerners got around to figuring it out.

BOB GARFIELD:

I guess the most pessimistic view of the phenomenon is that languages disappear through the process of something like cultural imperialism as local cultures become assimilated by the larger culture.

But another way of looking at it is that people are trying to make better lives for their children, and, through education, try to become more actively engaged in the larger culture. That's a bit of a conundrum.

GREG ANDERSON:

There is something to be said about adapting to the reality of the socioeconomics of your environment, so that if language X is the one that's going to get you ahead through education, then, of course, you need to know [LAUGHS] language X.

But that doesn't mean you have to abandon your original heritage, identity, ever, in any sense. There's no reason why you can't adopt the other language just as easily, because bilingualism is a normal state for people all around the world.

BOB GARFIELD:

Now, there are some languages that are undergoing some degree of resurgence. Gaelic is one of them. Can you give me some examples?

GREG ANDERSON:

Here in America, probably the greatest success story would belong to Hawaiian. Thirty or forty years ago, Hawaiian was in a very precarious state with very few speakers and very few native speakers at that. And through the efforts of a dedicated group of individuals, you have had a real resurgence in Hawaiian. That's a really great success story.

There are some moderate success stories happening. We have one here in Oregon. The Grande Ronde Reservation has been doing a really, really great language immersion program in the Chinook Wawa language, and that's producing a new generation of speakers of that language.

So, you know, there're lots of little pockets of success stories, for sure. You know, it's not all [LAUGHS] gloom and doom.

BOB GARFIELD:

Now, in your work, you know, you actually go to remote parts of the world with tape recording equipment to try to preserve languages, and sometimes you arrive [LAUGHS] in very out-of-the-way places only to discover that, well, the challenges are pretty substantial. Tell me some of what you've experienced.

GREG ANDERSON:

We arrive in this community in Central Siberia, and this language was last visited by linguists 30-plus years previously, so we weren't really sure if we were going to find any speakers at all, because the language was already in a precarious state then.

The first village we end up in, the mayor of the town gets this guy to help us and he takes us to another village on down the road. And we go there and [LAUGHS] the first guy we meet is completely deaf. And he's also missing all of his teeth. And so, you know, he's not an ideal consultant -

BOB GARFIELD:

[LAUGHS]

GREG ANDERSON:

- [LAUGHING] for a variety of reasons. He can't understand anything you say and he also has serious trouble pronouncing things.

So then they took us down the street to an elderly woman who both had all her teeth and not deaf, but just completely senile. So -

BOB GARFIELD:

[LAUGHS]

GREG ANDERSON:

- she was, you know, and didn't - [LAUGHS] she was an absolute character, because she would intermittently, you know, hug us and then start swearing at us, like — “Who are you and what are you doing here” and then, you know, like, “I love you” two minutes later.

And if your two people are someone who's completely deaf and someone who's really, you know, not connected into our personal understanding [LAUGHS] of reality, then you really have no chance of working with them. So that language is effectively dead.

As it turns out, we were able to find people that did, in fact, speak the language, but we managed to only find five of those people across this fairly large area. So the language is in an extremely precarious state.

But we've begun a very, you know, rigorous, systematic study since then with the use of the five remaining speakers.

BOB GARFIELD:

The idea of recording the last speakers to put in, you know, some sort of virtual warehouse to me suggests that scene in Fahrenheit 451 where in a society where all the books are burned, a handful of people repair to the forest where they learn books by heart and, you know, become the last living connection to a world where there's freedom of expression.

If five or six languages, Russian and Mandarin and English and Spanish, dominate the world, are we facing some sort of linguistic totalitarianism?

GREG ANDERSON:

I don't know if I'd go [LAUGHS] that far, but we are definitely facing is the loss of the vast majority of what we could ever know about the human mind as expressed through language.

Language is a very integral part of being human, and different systems of slicing up the human experience and expressing that, as different languages do, through words and grammar and whatnot, there's only so many of those that ever will occur.

But when we're faced with a world in which only Indonesian, Chinese, Spanish, English and Arabic and a few other languages still exist, just a tiny fraction of what humans once did will be ever knowable. [LAUGHING] And that's really a daunting and horrible thought, but that is the reality that we're facing.

BOB GARFIELD:

Greg, thank you so much.

GREG ANDERSON:

Bob, thanks for having me.

BOB GARFIELD:

Greg Anderson is the director of The Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages.