Transcript

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

From WNYC in New York, this is NPR's On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD:

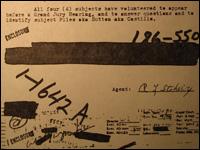

And I'm Bob Garfield. Back in the '80s, the Church of Scientology wanted to know what kinds of information the federal government was collecting on it, and so the church did what journalists do all the time. It filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, which requires government agencies to provide an initial response within 20 days. That was in 1987.

As of this week, the State Department still has not answered the Church's request. It's the oldest outstanding FOIA request, but hardly the only one.

This week, just in time for the 40th anniversary of the act's implementation, the watchdog group National Security Archive released a survey of government responsiveness under FOIA. It found that 53 of 57 government agencies had huge backlogs of unfilled FOIA requests.

Meredith Fuchs is General Counsel at the National Security Archive and she joins us now. Meredith, thanks for coming on.

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Thanks for having me on the show.

BOB GARFIELD:

Is there one federal agency that's the biggest culprit, that's withholding the most material?

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Well, the type of requests vary significantly by agency, and so what we've seen typically is the oldest requests are at the CIA, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the ones that do have harder requests to process, because they often might have classified information in them.

BOB GARFIELD:

By and large, of the requests that are being sat on, can the government make a good claim that they cannot dare divulge the information that's being requested?

MEREDITH FUCHS:

I don't think that's the case. While there are some that have sensitive information in them, there are also situations where agencies simply are not handling these requests.

For example, my organization alone has gotten 40-some-odd letters from the Treasury Department indicating that our FOIA requests were destroyed in error and were never processed.

Also, under a memo that was issued by Attorney General Ashcroft at the Justice Department - it was issued in 2001 and it basically instructed agencies to withhold if they have any possible basis for withholding. That differed from the policy of the prior Attorney General, Janet Reno, which basically said that agencies should disclose, unless there was a foreseeable harm from disclosure.

BOB GARFIELD:

Yeah. In her piece on the subject, Deborah Howell of The Washington Post [LAUGHING] talked about a FOIA request for a government press release. They fulfilled the request, but the press release came redacted. Portions [LAUGHS] were covered in black. Now, this was not a classified document. It was a press release!

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Well, that's what I'm saying about the reflexive secrecy. I mean, people look at these things and sometimes they just don't think. And they see something that might be a name that looks sensitive or a country that we have a current sensitivity with, and they just black it out.

In fact, we have documents that we received under FOIA a decade ago that if we requested them today they would come completely blacked out.

BOB GARFIELD:

Well, speaking of the Justice Department, it's right in the thick of the debate on a legislative fix to FOIA called the OPEN Government Act, which passed in the House but which is being held up in the Senate because one senator, acting on behalf of Justice, has put a procedural hold on the bill. Can you tell me about the situation that's going on there with Senator Kyl from Arizona?

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Well, it's sort of remarkable that an open government law was being held up by a secret hold. But thanks to efforts of many journalists across the country, we figured out that it was Senator Kyl. And he has some reasons why he's concerned about the bill, but until now my impression is that he hasn't been very open to trying to reach a compromise.

One of his main concerns was that agencies would lose their opportunity to withhold records if they were too slow in responding. But that's been changed now by a manager's amendment that was introduced by Senators Leahy and Cornyn, the cosponsors. I think that all of Congress, Democrats and Republicans alike, realize that the public is fed up with the administration's resistance to being accountable.

BOB GARFIELD:

Do you think that the backlash will cause Senator Kyl to back off, and the Justice Department as well?

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Well, it definitely seems like reforms come after controversies like the ones we see today. You know, in 1974, the Congress passed FOIA reforms and President Ford vetoed them, and Congress overrode that veto, which is just a remarkable story, because I think it shows that Congress can actually push back against an administration that wants to keep things secret and can let the public know that Congress is watching out for their interest.

BOB GARFIELD:

Meredith, thanks so much.

MEREDITH FUCHS:

Thank you so much for having me today.

BOB GARFIELD:

Meredith Fuchs is general counsel for the National Security Archive, an independent research institute in Washington, DC.