Transcript

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

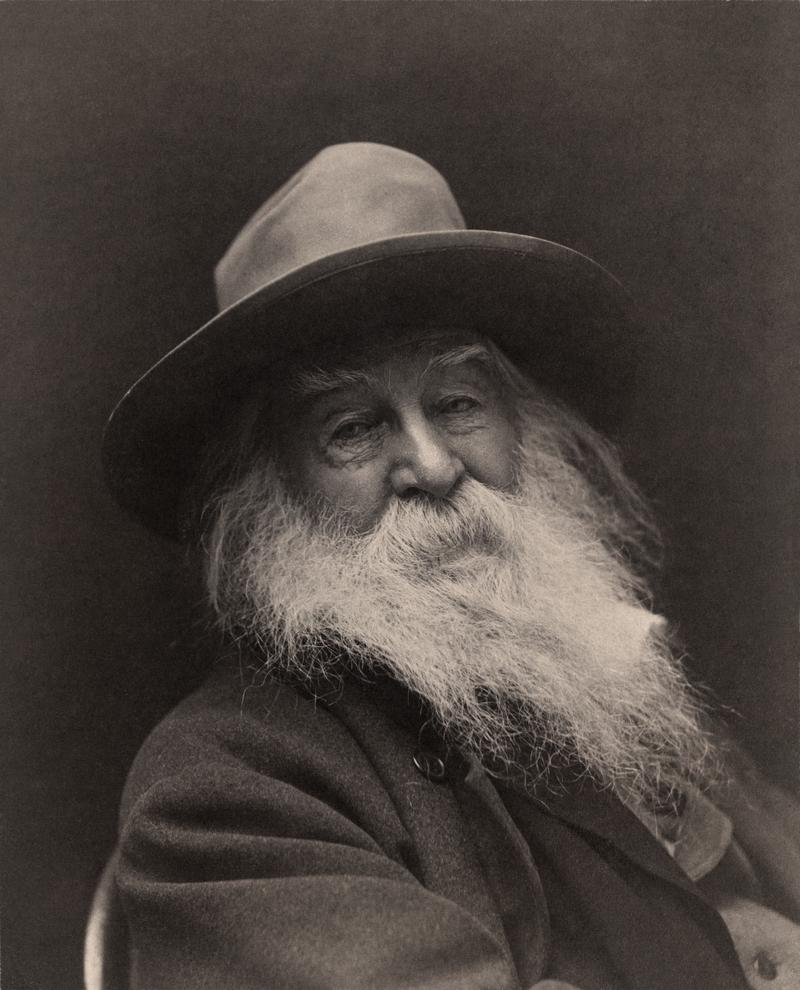

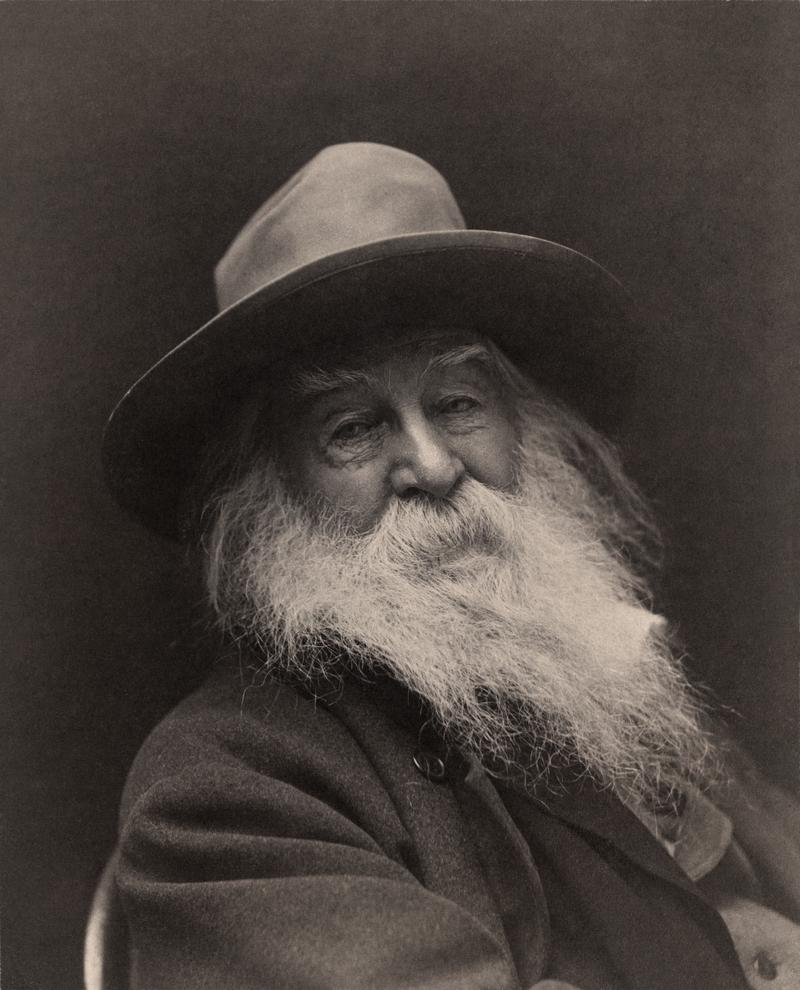

On March 1st, 1882, Boston District Attorney Oliver Stevens wrote a letter to the renowned publisher James Osgood regarding the delicate matter of a new book that was deemed to be in violation of the city's statute against obscene literature. Osgood took up the matter with the author, urging him to remove the offending poems and passages in order to appease, quote, "the official mind." The author refused, and the book, Leaves of Grass, was pulled from publication.

It turns out that James R. Osgood & Company had also issued The Prince and the Pauper, by Mark Twain, who was moved to defend Walt Whitman against what he thought was arbitrary censorship. Twain dusted off the old cannon, found offensive passages by Shakespeare, Swift and a dozen other lights of literature, and penned a letter to the editor of The Boston Evening Post.

MARK TWAIN IMPERSONATOR:

"A century or so ago, the foulest writings could not soil the English mind because it was already defiled past defilement. But those same writings find a very different clientage to work upon now."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Twain argued, slyly, that just because a book was harmless 100 years ago, it doesn't follow that it's harmless today.

MARK TWAIN IMPERSONATOR:

"If you will allow that the question of real importance is which are more harmful, the old bad books or the new bad books, permit me then to institute some comparisons."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Twain went on to cite the offending passages inside of Rabelais, Boccaccio, Shakespeare, et al. But you've never seen this letter to the editor in any Twain compendium because it was never published. In fact, it was never sent, because it was never finished.

It will appear for the first time anywhere in the current issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review, introduced and annotated by Ed Folsom, professor of American Literature at the University of Iowa.

ED FOLSOM:

From our perspective now, looking back on Walt Whitman and Mark Twain, we're looking back on the discoverers of a democratic form and a democratic voice.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

What makes their work democratic?

ED FOLSOM:

They began to break the traditional conception of the author speaking as authority over the people. Walt Whitman worked very hard in Leaves of Grass to construct a voice that would speak what he believed all people eventually would speak, even though no one could yet speak that voice, including him in his own personal life, but he could imagine that voice.

Mark Twain, on the other hand, turns a novel over to a relatively uneducated 14-year-old boy, a boy speaking to us in the dialect of the common people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

You note, though, that Whitman didn't always have kind words for Twain, and vice versa.

ED FOLSOM:

The thing that Walt Whitman did not like about Mark Twain was that he felt in some ways Mark Twain was playing at being that democrat that we just talked about. He was playing at being a writer of the people when, in fact, he was living a quite elegant and privileged life, unlike Walt Whitman, who was living in a tiny little home in dirty industrial Camden, New Jersey. Mark Twain was living in his mansion. He was a society figure, mixing with the most famous people of his time, talking to presidents and so on. Whitman, I think, always felt a little democratically superior, if that's not an oxymoron -

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS]

ED FOLSOM:

- by being the person who was actually living the life of the people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

But if Mark Twain was playing at democracy, he was playing with very serious intent when he wrote that satirical letter to The Boston Evening Post. How did the alleged obscenity of Leaves of Grass come to the attention of the Boston D.A.?

ED FOLSOM:

Well, this was the time of the now-infamous figure Anthony Comstock. Anthony Comstock was a reformer who wanted to get rid of filth and obscenity in American life. Part of the effect of the Comstock revolution was that medical schools had problems for a while even getting textbooks because Comstock would get these -

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS]

ED FOLSOM:

- laws passed that would make it illegal to send any lascivious material, defined as material showing naked bodies, through the mail. He made it his mission to set up Societies for the Prevention of Vice, as they were called, and one of the strongest was in Boston. Now, that Society for the Prevention of Vice got started about 9 or 10 years before they finally scored their big catch by getting Leaves of Grass ruled obscene.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

But what about Leaves of Grass in particular was deemed offensive?

ED FOLSOM:

Well, there's the famous Section Five of Song of Myself that begins, "I mind how once we lay such a transparent summer morning, how you settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me and parted the shirt from my bosom bone and plunged your tongue to my bare stripped heart and reached till you felt my beard and reached till you held my feet."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Oh, stop! Stop!

[LAUGHTER]

And so Twain set out, in his own inimitable way, to puncture the notion of what was deemed offensive. He writes -

TWAIN IMPERSONATOR:

"I think I can show by a few extracts that in the matters of coarseness, obscenity and power to excite salacious passions, Walt Whitman's book is refined and colorless and impotent, contrasted with that other and more widely-read batch of literature."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So what are some of your favorite of these extracts that Twain used in his letter to the editor?

ED FOLSOM:

Twain uses, of course, two sets of extracts. One set of extracts are the extracts from Leaves of Grass itself. "I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart. Copulation is no more rank to me than death is."

I love Twain's comment on that passage. He says, "It does seem unnecessarily broad, it is true," [BROOKE LAUGHS]

ED FOLSOM:

"but observe how pale and delicate it is when you put it alongside this passage from Rabelais, 13th chapter."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Go ahead and read a little bit of that Rabelais.

ED FOLSOM:

Sure. "How is that, said Grangousier. I have, answered Gargantua, by long and curious experience, found out a means to wipe my bum, the most lordly, the most excellent, the most convenient that ever was seen. What is that, said Grangousier, how is it? I will tell you by-and-by, said Gargantua. Once I did wipe me with a gentle-woman's velvet mask, and found it to be good; for the softness of the silk was very voluptuous and pleasant to my fundament." And on and on and on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS] It seems to me, though, by quoting Rabelais and Boccaccio and even Casanova, he's sort of stacking the deck. You know, when he says to the putative editor of The Boston Evening Post that all of these books are likely to be on your own bookshelf, do you think he was speaking the truth?

ED FOLSOM:

He mentions a lot of books right at the beginning of the letter, including Tom Jones, Joseph Andrews, Smallet's work, Byron, Burns; Gulliver's Travels he quotes from. And I think the interesting thing is that Twain knew that newspapers would censor whatever he wrote that would verge on the obscene.

And so, in this unpublished letter to the editor, Twain very carefully begins the passages and then he just marks little asterisks for the rest of the passages, and he always then puts a little bracket, imagining how it would appear in the newspaper, and in that bracket he would have little statements like, "We are obliged to omit it. Editor of Post.”

He could make his point precisely because the reader would be intrigued enough [BROOKE LAUGHS] to actually go get those books off his shelf or go to the library and get them. Twain's point was they're readily available. I'm going to get you started by telling you, here's a really dirty passage [BROOKE LAUGHS] in Rabelais. Now you go look it up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Now, Twain's letter ends with a tantalizing fragment. He writes, "Whitman's noble work” --

ED FOLSOM:

Yeah. My favorite part of this letter is its unfinished nature, because Twain was very sensitive about a number of people who had made comments like, well, what you're doing in fiction is sort of what Walt Whitman did in his poetry, and Twain bristled at the idea that he was imitating someone else's ideas.

And so, what lingers in that little fragment is Mark Twain's affirmation of the nobility of Whitman's work, something that he never affirmed that directly anywhere else: "Whitman's noble work."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

It was a pleasure talking to you, Ed. Thank you very much.

ED FOLSOM:

Thank you, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Ed Folsom is professor of American literature at the University of Iowa. His annotated version of Twain's letter, titled The Walt Whitman Controversy, is in the current issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review.