The Tariff Week From Hell. Plus, the Bluesky CEO Reimagines Social Media.

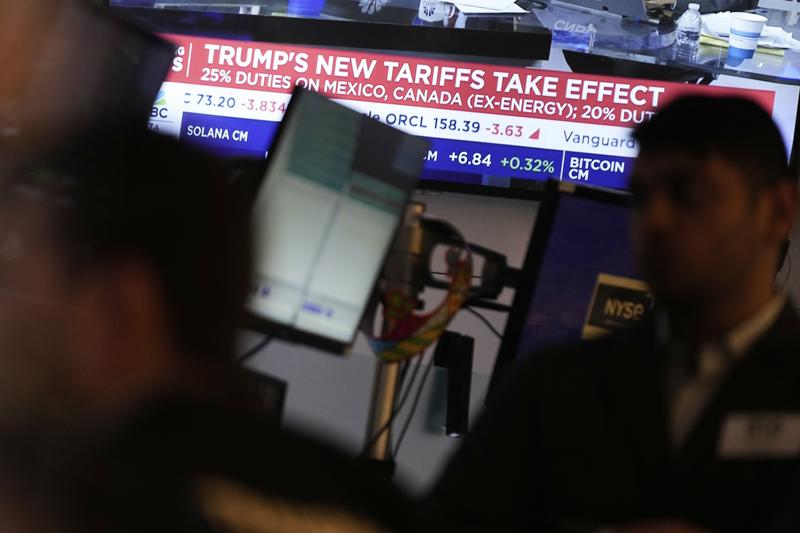

( Seth Wenig / AP Photo )

Sean Hannity: Today is Liberation Day and the start of a new golden age of American wealth and exceptionalism.

Brooke Gladstone: The right-wing spin machine went into overdrive this week, explaining away the economic turmoil caused by Trump's tariffs. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. Also on this week's show, the CEO of Bluesky shares her ideas of how to billionaire-proof the internet.

Jay Graber: Well, Zuckerberg has built a digital empire, and it's one man at the top of it. I want people to realize that we can build our own digital spaces. We can take that back.

Brooke Gladstone: Plus, why the mega rich want to escape the reality they've created for the rest of us? We're just the first stage on the rocket, the disposable stage that they can jettison once they've made it to the next level. I promise you, they're not going to make it. There is no next level. This is it.

Micah Loewinger: It's all coming up after this.

Brooke Gladstone: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. The week began with a bit of foreshadowing. A bogus story that briefly juiced an anxiety-riddled Wall Street. It all started with this Monday morning Fox interview with Kevin Hassett, Trump's director of the National Economic Council.

Male Speaker 1: Will you do a 90-day pause? Would you consider that?

Kevin Hassett: Yes, I think that the President is going to decide what the President is going to decide.

Micah Loewinger: To me, that sounded like Hassett was saying no, or at least just trying to dodge the question, but one popular user on X interpreted it differently.

Male Speaker 2: His little yep or yah or yeah, depending on how you heard, was apparently enough for a social media user who goes by the name Walter Bloomberg. No relation to the billionaire or the business news outlet, just someone who amplifies a lot of Bloomberg content.

Micah Loewinger: The Walter Bloomberg account posted that, according to Hassett, Trump was considering the 90-day pause on all countries except China. Two minutes later, a CNBC host live on air picked it up.

Male Speaker 3: I think we can go with this headline, from apparently, Hassett's been saying that Trump will consider a 90-day pause in tariffs for all countries except for China.

Micah Loewinger: For Reuters, that exchange on CNBC was enough to run its own story. Within minutes, Wall Street was riding the hype train.

Male Speaker 4: The Dow swinging 2,600 points, the most in one day ever. The S&P 500 at one point gaining back $2.4 trillion in market value.

Micah Loewinger: But just as quickly, the hype train went off the rails.

Male Speaker 2: A couple of minutes later, the Dow industrials had shot up a thousand points only to collapse again at 10:39 when the White House quick response team put up this three-word post, "Wrong fake news."

Micah Loewinger: By Tuesday, the cruel reality had set in. The tariffs were here to stay.

Male Speaker 5: Stocks tumbled into the red with a Dow falling for the fourth straight day, down roughly 300 points.

Batya Ungar-Sargon: The rage that you see on Wall Street, what they are trying to do here is they are shorting the President's agenda.

Micah Loewinger: MAGA pundit Batya Ungar-Sargon and others on Fox tried their darndest to put a patriotic shine on the mess.

Batya Ungar-Sargon: There has been a crisis in masculinity because we shipped jobs that gave men who work with their hands for a living off to other countries to build up their middle class.

Jesse Watters: When you sit behind a screen all day, it makes you a woman. Studies have shown this. Studies have shown this. If you are around other guys, you're not around HR ladies and lawyers-

Female Speaker 1: What do you do?

Jesse Watters: -that gives you estrogen.

Female Speaker 1: What do you do?

Micah Loewinger: The dubious economic theory at the heart of Trump's tariffs, and I guess Jesse Watters' gender panic is that making imports from other countries more expensive will force American companies to rethink global supply chains and bring all those manufacturing jobs back to the states. Never mind the fact that, because of advances in technology, modern factories employ fewer workers than those of the 1950s and that creating a recession probably won't incentivize businesses to invest in new American plants. That jacking up the prices on stuff we can't make here, or at least not for a while, hurts everyone, especially working people. But hey, talking points like evening the playing field and reciprocal tariffs have served the White House just fine up until now.

Markwayne Mullin: What the President is saying here is he's not wanting to start a trade war. He's simply wanting to even the playing field. Reciprocal tariffs isn't just about the tariffs, but it's also access to our economy. I say this--

Micah Loewinger: They're not reciprocal because, in most cases, Trump has been threatening much larger tariffs on imports from other countries than they are on US exports. Like Trump's 46% tax on goods from Vietnam versus Vietnam's roughly 5% tax on imports from America, a 41% difference that punishes American consumers because, remember, Americans pay Trump's tariffs. Anyway, how did the administration even come up with that 46% number?

Phil Mattingly: Let's take Vietnam, which is obviously a huge exporter to the United States because US people buy Vietnamese goods.

Micah Loewinger: Correspondent Phil Mattingly on CNN explaining the administration's formula, which was made public last week on so-called Liberation Day.

Phil Mattingly: Vietnam exports $136.6 billion in goods to the US, the US exports $13.1 billion in goods to Vietnam. Now, how did they get to the 46%? What they did is they subtracted the Vietnamese goods bought by the US, $136.6 billion total US goods bought by Vietnam, and ended up with $123.5 billion.

Micah Loewinger: That's the trade deficit with Vietnam, by the way. $123.5 billion. The fact that we buy so much more from them than they do from us is the basis of Trump's claim that we're being ripped off and that we need to rewire the global economy.

Phil Mattingly: Now, the way they actually got 46% is they did 123.5 divided by 136.6-

Micah Loewinger: That's the trade deficit divided by the amount we import from Vietnam.

Phil Mattingly: -which equals 0.90 or 90%.

Female Speaker 2: And then half of that.

Phil Mattingly: Then, because of the benevolence of President Trump, as he kind of laid it out, then they cut that in half.

Micah Loewinger: If you had trouble following that math, don't worry, you're not alone.

Phil Mattingly: Economists of all sides, all ideologies, Republican and Democrat, staring at the methodology and saying, that's not how this is supposed to work.

Jim Cramer: This is what they came up with. Geez, come on, have some gumption, have some math.

Micah Loewinger: That's CNBC Mad Money host Jim Cramer. The same pundit who told viewers that a second Trump presidency would be good for the stock market now says he was swindled.

Jim Cramer: Over and over again, the President said, "Listen, it's going to be reciprocal. So you do it, we do it." That was going to be so good, and I really believed in it and I feel like a sucker tonight.

Micah Loewinger: By midweek, other would-be Trump supporters were taking their grievances public, including Senator Rand Paul.

Senator Rand Paul: The whole debate is so fundamentally backwards and upsides down. It's based on a fallacy that somehow in a trade, someone must lose. If you want to sell me your coat and I give you $200 for it, we both agree to it and we're both happy with the trade.

Senator Ted Cruz: If these tariffs result in massively higher prices, result in driving up costs for US Companies, result in job losses, and put us into a recession.

Micah Loewinger: Senator Ted Cruz.

Senator Ted Cruz: If we go into a recession, 2026, in all likelihood politically, would be a bloodbath.

Ben Shapiro: It is a tax on American consumers. The idea that this is inherently good, it makes the American economy strong, is wrongheaded. It is untrue.

Micah Loewinger: Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro.

Ben Shapiro: The idea that is going to result in massive reshoring of manufacturing is also untrue.

Female Speaker 3: Add to that, billionaire hedge fund manager and Donald Trump supporter Bill Ackman is now somewhat leading Wall Street's backlash to the tariffs, calling Trump's tariff plan a "self-induced economic nuclear winter." Also saying, "This is not what we voted for."

Dave Portnoy: Trump has put his tariffs all over the place. I've been trying to understand them, I don't.

Micah Loewinger: Dave Portnoy, head honcho at Barstool Sports.

Dave Portnoy: $7 million. I'm down $7 million in stocks and crypto.

Micah Loewinger: Meanwhile, the MAGA faithful stayed the course.

Benny Johnson: Losing money costs you nothing. This is just the reality of life. Everyone loses money. It costs you nothing. In fact, it builds quite a bit of character. In fact, you learn a lot of lessons actually by losing money.

Female Speaker 4: Ignore the Dow doomsdayers. I don't really care about my 401k today. You know what? Not that I can afford it. Not that it isn't important. Not that I'm not at a point in my life when I should be worried about my 401k, because I am, but this is what I believe. I believe in this man.

Micah Loewinger: All this brings us to Wednesday, and you probably know what happens next.

Male Speaker 6: President Trump making big news this afternoon. He's just announced a 90-day pause on tariffs for many countries around the world.

Micah Loewinger: Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt framed the retrenchment as a success at the White House later that day.

Karoline Leavitt: We have had more than 75 countries from around the world reach out to President Trump and his team here at the White House to negotiate better trade deals for the American worker.

Micah Loewinger: When NBC asked for a list of said countries, the White House said, "No." At least at first, Wall Street didn't seem to care much for the details.

Male Speaker 7: Within minutes, Dow stocks soared more than 2,000 points, closing up nearly 3,000.

Female Speaker 5: NASDAQ up nearly 1,900 points. The second best day ever.

Male Speaker 8: The S&P seeing one of its biggest gains since World War II.

Micah Loewinger: This is the push notification I got from The New York Times on Wednesday. "S&P 500 surged 9.5%, its best day since October 2008 after President Trump backed down on, quote-unquote, 'reciprocal tariffs' for 90 days." Okay, for one, they're not reciprocal. Two, Trump didn't back down. He actually increased tariffs on Chinese imports and kept in place 10% universal tariffs that took effect on April 5th, which will still have a massive effect on the global economy. Three, the best day since October 2008. That's a reference to a brief market surge in the middle of the Great Recession. What's sometimes called a dead cat bounce. But The Times wasn't alone in regurgitating White House verbiage.

Female Speaker 6: We're hearing that President Trump has announced that there will be a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs.

Male Speaker 9: President Trump now says he will implement a 90-day pause on tariffs on imports from more than 75 countries.

Female Speaker 7: President Trump says the 90-day pause on his reciprocal tariffs means more time for his administration to negotiate deals with trade partners.

Male Speaker 10: We start tonight with stocks surging as President Trump announces a 90-day pause on some tariffs.

Micah Loewinger: How were those critics from just days earlier handling the latest news? Ted Cruz.

Ted Cruz: Trump has an opportunity to win a huge victory for American workers. I think today's announcement is an indication of his going down the path of lowering tariffs all over the world, but making sure--

Jim Cramer: Whiz-bang. What a move. Incredible.

Micah Loewinger: Jim Cramer on Mad Money.

Jim Cramer: NASDAQ shooting into orbit up 12.16%. Second best day on record.

Stephanie Ruhle: Today we saw investor and big-time Trump supporter Bill Ackman tweet, "This was brilliantly executed by Trump textbook, Art of the Deal."

Micah Loewinger: The Art of the Deal, Trump's 1987 book ghostwritten by journalist Tony Schwartz, who's since called it the--

Tony Schwartz: Greatest regret of my life without question.

Micah Loewinger: The most notable deals that Trump made this week, according to congressional Democrats like Adam Schiff, were ones he may have brokered for friends and family.

Adam Schiff: Insider trading within the White House, within the administration.

Micah Loewinger: See, just like Wall Street's fake news, sugar high from Monday, the surge on Wednesday was a momentary blip, except this time, Trump world was poised to profit. Hours before he made his announcement about the tariffs, Trump posted this to Truth Social.

Female Speaker 8: He said now is a great time to buy. That has some questioning. If that was a tipoff to investors.

Adam Schiff: The question is who knew what the president was going to do? Did people around the president trade stock knowing the incredible gyration the market was about to go through?

Micah Loewinger: Trump in the Oval Office on Wednesday with some visiting billionaires.

President Trump: He made $2.5 billion today, and he made $900 million. That's going to--

Micah Loewinger: Some people made off like bandits just before the market resumed tumbling when, on Thursday, Trump upped tariffs on Chinese goods to 145%.

Male Speaker 11: We begin this out with stocks falling following their biggest-

Micah Loewinger: Even as his supporters and spokespeople attempted to cast the events of the week as a brilliant master plan of a financial genius. Donald Trump himself said he just changed his mind after people got yippee, but there's a deeper story here about how Trump has attempted to circumvent Congress.

Male Speaker 12: President Trump declared a national emergency, and by doing so, he created the ability for himself and only himself to regulate and impose tariffs across the board on lots of different countries.

Micah Loewinger: Trump declared a state of emergency on the influx of fentanyl from Canada and at the border with Mexico, invoking the Enemy Aliens Act to deport some migrants without due process. He said there was an energy emergency when he forced California to open its dams after the wildfires. He said there's a lumber emergency in order to skirt environmental safeguards for logging. In short, we have a leader who declares a national emergency anytime he wants to sidestep checks and balances, creating crises that further entrench presidential power. That may prove to be the greatest national emergency of them all.

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, the CEO of Bluesky, on making her website billionaire resistant.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media.

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. Ever since Elon Musk bought Twitter in October 2022, disaffected tweeters have been leaving the platform in fits, bursts and droves.

Female Speaker 9: Announcement, I am about to delete my Twitter.

Female Speaker 10: We'll call it the Exodus from X.

Male Speaker 13: Some news outlets have decided to quit X, formerly known as Twitter.

Female Speaker 11: The day after the election. X lost more users than any day since Elon Musk bought it in 2022.

Micah Loewinger: Some went to Threads, some went to Mastodon, and others went to--

Female Speaker 12: Bluesky, welcoming 2.5 million new users in the last week.

Male Speaker 14: Bluesky was originally created by former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey in 2019. It's been around for a while, but it was recently opened to everyone.

Micah Loewinger: Bluesky's 30-odd million users are just a fraction of the hundreds of millions of active users on X and Meta's Threads, but it's taken off with certain groups like journalists who were early to Twitter. It does kind of feel like early Twitter, but under the hood, there's an important difference.

Mike Masnick: The idea was to really try and move the control and power away from the center to the edges of the network.

Micah Loewinger: Mike Masnick is a longtime tech journalist and the founder and editor of Techdirt. Back in 2014, he was observing how Twitter and Reddit were struggling with their own respective content moderation challenges.

Mike Masnick: I was thinking about the earlier internet and earlier forms of the internet where there wasn't so much centralized power. There wasn't some billionaire sitting in Menlo Park, deciding who could say what and do what. At the same time, I recognized that you didn't want a free-for-all because there were horrible people who would do horrible things and that would scare away other people, so I started to try and think through, like, is there a different approach?

Micah Loewinger: His idea, what if social media ran on a protocol, similar to the HTTP that the internet runs on, letting users access any website from any browser? He used the example of the protocol that email runs on.

Mike Masnick: If you don't like what Google is doing with Gmail, you can switch to Proton Mail or Yahoo Mail or Outlook, and you can still email the people at the other places. You don't lose all of your contacts. You can also put in place all different kinds of spam filters or other tools where the power is in the hands of the actual user, and they can determine what it is that they want to do and how they want to experience email.

Micah Loewinger: Which is fundamentally different from how most social media platforms work.

Mike Masnick: If you leave Facebook and all your family uses Facebook, you can't really communicate with them in the same way. There's no alternative to Facebook that allows you to continue to communicate with the people that you wanted to communicate with on Facebook.

Micah Loewinger: At the time, the idea of getting a critical mass of users to switch over to a new social media site seemed unlikely to Masnick. His best bet, he thought, was to convince the existing social media companies to adopt this protocol-based approach. He brought the idea to higher-ups at Snapchat and Facebook.

Mike Masnick: I don't think the person at Snapchat even understood what I was talking about, but the person at Facebook was like, "There's no way. Facebook will never do anything like this. This is like a crazy idea, and it's a stupid idea."

Micah Loewinger: So he put these crazy ideas together in a paper called Protocols, Not Platforms, published in 2019.

Mike Masnick: I assume that I'm going to write this and I'm going to be that weird crank who has this philosophical approach to the way the world would be better. Nobody listens to me, and occasionally I'll yell from my shack in the woods about how the world could be better if only people listened to me.

Micah Loewinger: But that's not what happened.

Mike Masnick: Someone had sent Jack Dorsey my paper, and he wanted to have a call with me and said, "At Twitter, we've been having all these big existential discussions about what should Twitter be and how should it work." He said when he read my paper, it sort of clicked that this was the answer to the debate that they'd been having internally.

Micah Loewinger: And they built it.

Mike Masnick: Actually seeing something that I wrote turn into this is wild. Never in my wildest dreams that I actually think something like that would actually happen.

Jay Graber: Mike Masnick is on our board now.

Micah Loewinger: Jay Graber was hired by Jack Dorsey to lead the project and is now the CEO of Bluesky. When I spoke to Jay this week, I started our conversation by asking her about her given name, Lantian, which happens to mean Bluesky in Mandarin.

Jay Graber: Yes. Coincidence.

Micah Loewinger: So you did not name the site after yourself?

Jay Graber: No, Twitter named the site, and then I saw that they had this project called Bluesky that was decentralized social, and I was like, "Oh, this is something I must work on, because I'm already working on a decentralized social network."

Micah Loewinger: You're now CEO of this hot new social media company. What have you learned about the internet that you didn't know before your product really caught on?

Jay Graber: There's been a lot of lessons as we've scaled up, because we've grown by 10x multiple times, and that's a lot of growth in just a bit over a year. We opened up to the public last February. Users don't like a lot of complexity. You have to make it really easy for them. That's why when you get into the Bluesky app, it looks and works just like old Twitter did. Then, under the hood, you actually have all this choice. Over time, we've been showing people how to use these customization options and explaining it to them, but it's not something that's intuitive immediately, because people are used to centralized sites that don't give you any choice or control.

Micah Loewinger: Yes, let's talk about a little bit of that customization. One thing you can change is how your feed is moderated, how posts are filtered or emphasized to you. You've called it a stackable approach to content moderation. Give me some examples about specific ways that people can tailor their experience.

Jay Graber: An example of this would be somebody's built an AI art labeler, because some artists want to know if the art they're looking at is made by a human artist or is AI-generated. Now, this isn't something that we have a foundational moderation policy on, but if you report a post to the AI art labeler, it will tag it as AI art. Then if you subscribe to that labeler, you can say, I want to see this. I want to have it labeled, so I just get the warning label on it, or maybe I'll turn it off for now. People have built labelers for screenshots from other sites, for political content. Then you can use these filters to cut down what you see so that you're in a space that you want to be in.

Micah Loewinger: Last year, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg wore a shirt that said, "Either Zuck or nothing," in Latin at a developer conference. It was a play on the phrase "Caesar or nothing." Positioning himself, Mark Zuckerberg, as Caesar. This year at South by Southwest, you wore a shirt that said, "A world without Caesars," also in Latin. What specifically about Zuckerberg and Facebook did you see as something worth making this public statement about?

Jay Graber: Well, Zuckerberg has built a digital empire, and it's one man at the top of it. We've helped him build that with our data and our time. I want people to realize that we can take that back. We can build our own digital spaces on an open protocol where anyone can get involved. We want to live in a world without Caesars. We want to live in a democracy, and we want our online social spaces to reflect that.

Micah Loewinger: You've said that Bluesky is billionaire-proof. This has become a marketing term for the site. What do you mean by that? How is it billionaire-proof?

Jay Graber: What this means is that if a billionaire acquired the Bluesky company or did something to take over the foundation that Bluesky is built upon, lets users freely migrate. If something happened down the road where Bluesky changed hands, like we've seen with other social companies, users could move over to another app and, importantly, keep all of their relationships and their followers and their same username. This reduces the incentive, actually, for billionaires to come and make a big change with Bluesky, or for me to drastically change business direction because we would lose users.

Micah Loewinger: Okay. Of course, the elephant in the room is that Bluesky, like every other social media site, needs to make money. You've said that Bluesky won't sell ads or profit off of user data. It's important to note that these are two major things that have denigrated the user experience on other social media sites. I know you're familiar with the term enshittification from Cory Doctorow. He's referring to this experience by which pushes to profit off of big platforms, makes them worse. X and Facebook feeds are now filled with annoying ads. We know that they're violating our privacy with surveillance in certain ways, but this is how they make money.

Bluesky was founded with a grant from Twitter. It's since received venture Capital funding, but you're still a long way from making money. Doesn't that leave the company vulnerable to a hostile takeover like what we saw from Elon Musk? If you build up something big, what's stopping a billionaire from coming and trying to squeeze it for all it's worth?

Jay Graber: Yes, I think the important thing here is to understand that we're open source all the way up. What this means is that the power of exit, so the right for users to leave, is built into the System. If Bluesky, the company were to enshittify, for example, if Bluesky starts sticking ads in between every single post on the main algorithm that we provide as a default when you sign up, there's actually thousands of other algorithms you can switch to and you can just move your timeline over and uninstall the one that's the default. Then you wouldn't be on our own feed, even within the Bluesky app. That means we want to keep that feed good. We don't want to shove so many ads in that you get sick of it.

Micah Loewinger: Are ads on the way for Bluesky?

Jay Graber: The first thing actually is subscriptions. That's on the way soon. We're not exploring ads right now. There's people in the ecosystem doing sponsored posts in their feeds, and we're seeing how it plays out because one thing we've said is that in an attention economy, at some point ads work their way in. I think that the way it's going to emerge in the Bluesky ecosystem is a bit more like the web outside of social companies, where in Google search, sometimes you get ads, but it's not shoved between every search result.

Micah Loewinger: Right now, the way that you think that Bluesky can become financially sustainable is first and foremost through a subscription service.

Jay Graber: It's one of the first steps. We think one of the most exciting things long-term is actually marketplace models where we're creating connections between creators and their audiences, users and these other developer-driven experiences and sites, and then taking a cut when people do transactions or exchange value. People are already paying each other for feeds for stuff that other people have created. We would eventually like to build out a marketplace that supports all of these things.

Micah Loewinger: One way that Bluesky has set itself apart from, say, X/Twitter, is that your site doesn't downrank links. I can tell you as somebody in the media business, we journalists like when people click on our links, even if that means that, hey, they leave your social network for a little while to read our article, or listen to our podcast. Media companies in the past have been really burned by Facebook and Twitter. These were companies that courted news publishers. Facebook even went as far as to pay newsrooms to post more on their site, but then they kind of did this about-face. They changed their strategy, they deprioritized news and links, and a lot of companies just didn't recover.

Today, big and small news outlets alike, from The Boston Globe to The Guardian to The New York Times, have reported seeing considerably higher traffic from their links on Bluesky than on competitors like X and Threads. Despite Bluesky having a much smaller user base right now. What role do you see Bluesky playing in our kind of news industry crisis moment?

Jay Graber: Other sites let you grow your audience up until you want to convert them and take them off through a link to subscribe or to read your article. Then they downrank that because they want to keep you scrolling on their timeline, because that's where they're showing you ads. By not pursuing this single timeline ad-driven model, what we're doing is being a neutral gateway. We're just passing users directly through to show them the stuff that they're following. It's a simple concept, but it means that people get a direct connection with their followers, and they get way more traffic and subscriptions as a result. We're not trying to stall users on our site to capture that ad traffic.

Micah Loewinger: One of the features you've added for the benefit of news companies is link tracking. This is a kind of ethical fuzzy area that I want to unpack with you. This is useful for publishers like On the Media because we want to see where audiences are finding out about our show and clicking on our stuff. It also means that you at Bluesky are tracking what users click on, which is a kind of surveillance. In the era of a Trump presidency, is it fair to see this as potentially dangerous? For instance, couldn't the government, in theory, subpoena Bluesky for information about, say, who clicked on a petition or protest signup form? If you have that data, is it ripe for the picking by the wrong people?

Jay Graber: Our goal here is to help sites understand that their traffic is coming from Bluesky. This works like a website that just lets users see when they link between them. On the web, this information is usually sent by the user's browser, so we're just providing parity to that behavior. There's not a back-channel or cookie tracking that follows you elsewhere or anything like that. It's just the basic facilities of a web browser. That helps sites understand where their traffic is coming from. Now, down the road, I think we would like to give people the option to opt out of this if it's something that they're really concerned about.

Micah Loewinger: You've staked yourself out as an anti-tech billionaire tech CEO, but we live in a time where we've seen so many idealistic people in Silicon Valley abuse our trust. I know that you're building a protocol that exists outside of you, but how can we trust you, Jay?

Jay Graber: First of all, my intention is to build an open system that retains user trust. The beauty of this approach is actually that if we ever drift from this alignment that we've set out, we've built ourselves on an open foundation that lets users have the power to leave without losing their social graph.

Micah Loewinger: Basically, the idea is that we don't need to trust you.

Jay Graber: That's the goal. I think we should have an online world where if a website or an app abuses your trust, you have options to leave. If a news site where you were reading news started to abuse your trust and tell you lies and jam ads in everywhere, you would just use a different news site.

Micah Loewinger: It's funny because even while so many people in the tech governance world are supporting what you're doing, there are already plans to protect Bluesky from eventual or potential corruption. I'm sure you're familiar with the Free Our Feeds initiative, which is a nonprofit foundation that's raising funds to protect Bluesky's protocol from tampering. In effect, they're trying to protect your creation from you. How do you feel about that project?

Jay Graber: I think that's healthy. This means that there will be a diversity of experiences out there. Bluesky will be one app in the broader atmosphere, which is what we call the broader AT protocol ecosystem. You could choose between two different microblogging apps, or you could choose between the Bluesky microblogging app and the Skylight Social, which is a video app, or the Flashes app, which is a Instagram-style photo app. Those are all run by different people. Those are run by developers outside the Bluesky company who will be operating according to their own principles.

Micah Loewinger: You said something really interesting recently that I want to ask you to expand upon. You said societies start to reflect the structure of its dominant form of communication. How has centralization of social media produced this political moment?

Jay Graber: I think centralization means that you really have one point of pressure. One sort of nerdy analogy I use is it's like the one ring of power, that means that you can control the speech of billions if you own a major social platform. Then everyone wants that control. Billionaires will try to purchase it. Governments will also go after that point of control. I think that having more diversity of companies that are operating this ecosystem means that you will have different CEOs who make different choices.

Micah Loewinger: What's at stake if we don't redefine how we communicate online?

Jay Graber: I think the future of democracy is at stake because democracy depends upon pluralism, people being able to have different viewpoints, find compromises. Right now, social media, I think, has accelerated some of that breakdown in our belief in democratic norms. I don't think a single app is the solution. I think having an ecosystem where new solutions can be built is the path forward. You want a way where people with ideas on how do we improve the state of discourse? How do we address misinformation? They don't have to wait for a single CEO to make a decision to address this. They can start building a solution themselves off to the side and say, "Hey, try this out," or they can integrate it into the application because it's an open platform. Those are the ways I think we will more quickly find a path forward that allows democracy to survive and thrive.

Micah Loewinger: Jay, thank you very much.

Jay Graber: Thank you.

Micah Loewinger: Jay Graber is the CEO of Bluesky.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, the tech titans, some of them anyway, seem eager to run away from the world they helped create.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media. This is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. This month, Forbes published its annual list of billionaires. Turns out that not only are there more of them than ever, 3,028 and counting, but that they have accumulated more wealth than ever.

Female Speaker 13: The rich are getting richer. Collectively, the billionaires made almost $2 trillion more than they did last year, and last year was record-breaking.

Brooke Gladstone: They're more influential now with a large cluster of them in the federal government.

Male Speaker 15: People like Howard Lutnick, Steven Feinberg, spouses of billionaires, Linda McMahon, Kelly Loeffler. That's not even mentioning Elon Musk, who, of course, is number one on the list with over $300 billion.

Brooke Gladstone: In Ayn Rand's book Atlas Shrugged. The Rich and the Talented, fed up with government constraints on their free will, abandon America for a utopia and leave the rest of us to perish in our own mediocrity. Elon Musk had his eyes on Mars, where he hopes to send a rocket one day to fulfill his lifelong goal of building a colony off-world.

Elon Musk: That's the overarching goal of the company, is extend life sustainably to another planet. Mars is the only option, really. Ideally, before World War III or some kind of bad thing.

Brooke Gladstone: Douglas Rushkoff has written about the philosophy, culture, and evolution of life online for as long as there's been one. I spoke to Doug in the fall about his book Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires, which opens in a remote desert where Rushkoff meets five unnamed tech titans who want him to assess their strategies for survival after what they call the event.

Douglas Rushkoff: Right, that's the lingo, the word they use to describe the apocalypse or climate catastrophe or pandemic that wipes out humanity.

Brooke Gladstone: There are actual places, a safe haven project in Princeton, an ultra elite shelter in the Czech Republic.

Douglas Rushkoff: The worst ones are where they build a fortress and surround it with kerosene-filled lakes that they can light on fire as the masses storm their gates for food, armed with Navy SEALs protecting their organic permaculture farms. Mark Zuckerberg has a rather impenetrable estate out in Hawaii. Peter Thiel has been building something in New Zealand. One of the guys pulled out these plans he had for these shipping containers, and bury them underground and connect them all with tubes. If you end up with 8 or 10 or 15 shipping containers, you can have a big underground apartment. One of them had an indoor pool.

I asked him, I said, "My neighbor's always got these trucks in front of his house bringing replacement parts. What are you going to do for replacement parts in your heated pool once there's no pool places?" He pulls out this little Moleskine book, and he writes down there, "New parts for pool." What I realized is these guys are thinking just one level into the science fiction fantasy, but then when you push on it just a little bit, they're not thinking about it at all.

Brooke Gladstone: As a practical matter, you did debunk their plans because it's impossible to ensure survival amid global catastrophe. But you say fundamentally that's not what they really wanted from you.

Douglas Rushkoff: I think what they really wanted was for me to water test their survival strategies. Will this work? Will that work? Should I go to Alaska? Should I go to New Zealand? While I don't know whether Alaska or New Zealand will fare better, I do know something about what's driving these people. There in the moment, I felt a little bit more like an intellectual dominatrix. They hired me to make fun of what they were doing, to pull the rug out or, at worst, to make them suffer, make them feel guilty for wanting to move on and leave the rest of us behind.

Brooke Gladstone: In the book, you describe them as kind of self-styled Ubermensch who believes in scientism, that human beings can be reduced to their chemical components, and that's it. Only the truly superior understand that.

Douglas Rushkoff: Mark Zuckerberg he models himself after Augustus Caesar. Elon Musk sees himself as one of the Avengers, as Iron Man. They see themselves as demigods, living, as Peter Thiel would say, one level above the rest of us, one order of magnitude above humans.

Brooke Gladstone: Which brings us, I guess, to the core idea of your book, what you call the mindset.

Douglas Rushkoff: When I was introduced to the internet, it was through the California counterculture. We thought we were going to give people these tools and increase the creativity of the collective human imagination. It was that wonderful, psychedelic hippie rave. Along came Wired magazine and investors who decided, "Oh, no, rather than give people the tools to create a new reality, let's use these technologies on people in order to make them more predictable." Instead of giving people tools, we use tools on people.

For years, I blamed this on capitalism, and it's easy because there's a lot we can blame on it. As I met more of these people, I realized it was really intrinsic to their techno-pseudoscientific mindset. If all we are is information, all we are is DNA; that's all that matters. It dovetails perfectly with corporate capitalism, because capitalism it's just the numbers. Ray Kurzweil, one of the technologists at Google, really believes he can upload his consciousness to a computer and move on, because it's just data.

Brooke Gladstone: I was moved by your discussion with Ray Kurzweil. You made an impassioned argument for what you call the squishy stuff and its unquantifiable value in human experience. He just called that noise.

Douglas Rushkoff: I know. Wasn't that odd? He said, "Oh, Rushkoff, you're just saying that because you're human," as if it was hubris. Digital technologists, they understand all the little quantized notches, but anything that's not on that line is noise. That's why the aesthetic of the digital age is auto-tuning. You get that note exactly right. I understand maybe with a commercial artist like an Ariana Grande, you make a better recording by auto-tuning on that 440Hz a note. What if you auto-tune James Brown? When James Brown's reaching up for that note, it's that reaching up that the technologist considers noise because it's not on the note.

You and I understand that reaching, that's the true signal. That's the human being speaking through the music to us. It's the way we don't conform rather than the way we do. It's the soft, squishy stuff. That's what they don't understand. That's their fear. I realized this as I was writing this book, that these escape plans they have, they want to leave behind this weird, squishy, female, natural in between liminal world that's so confusing, it doesn't have numbers. They want to rise above this dirty, fertile matter and experience themselves as pure consciousness, just ones and zeros, where everything just makes sense.

Brooke Gladstone: You were writing this book back in 2022, but now with Trump's reascension to the White House, do you feel that the tech bros' ideas have gotten a big boost?

Douglas Rushkoff: It's strange. A lot of people with authoritarian ambitions have quoted my work. The Prime Minister of Italy was talking about Team Human, this book I wrote, really arguing for the human against this mechanistic understanding of the world. The far right grabbed onto that slogan. Steve Bannon read out loud five or ten pages of Team Human.

Brooke Gladstone: What did he like about it?

Douglas Rushkoff: It was interesting. Bannon and Meloni.

Brooke Gladstone: Giorgia Meloni, Italy's far-right PM.

Douglas Rushkoff: Yes, they see the Team Human revolt as taking a stand against the technocracy, that kind of Obama, Hillary reduction of our world by the technocrats. Now we see the right wing embracing the technocrats. Musk and other Silicon Valley demigods flipped in some ways from being part of the left to being part of the right. That's because they don't have political ideology. They just want to side with whoever's going to support their techno-dominating understanding of the world, their notions of progress and conquest. Because in the end, what we're looking at really is a continuation of the colonial urge by digital means. They've run out of physical territory. What do you take over? You take over the information space.

Brooke Gladstone: They sure have. Speaking purely of technology, you argue that even the philanthro-capitalists or the green technologists, they really have nothing for us.

Douglas Rushkoff: Even the most well-meaning technologists who are talking about doing humane technology, they're still kind of ass backwards in their perspective. "Oh, we can create humane technologies that undo the effects of these bad technologies." If you're using your smartphone too much and getting anxiety, we'll create a wellness app to undo the effects of the bad apps. The solution always involves more technology. Or, "Oh, we've destroyed the planet with all this, so now we're going to build high-tech eco villages run with sensors and AI that maximize the soil efficiency." Then whatever technological invention they've come up with becomes enslaved by the market. It has to now grow exponentially in order to even stay in business. All of these technologies are not really in service of humanity. They're still in service of these abstract financial markets.

Brooke Gladstone: You wrote that the tech titans, when they move fast and when they break things, they do it so they're not hit by falling debris. That the race to space, wealth or personal sovereignty is less running toward a vision than it is trying to run away from the resentment and the damage they're causing. You compare them a bit to Wile E. Coyote in the famous cartoon. He's always devising extravagant ways to ensnare his enemy, the roadrunner. Then he becomes the victim of his own invention, ends up out there in midair, looks down and goes down. You say the tech titans are going down?

Douglas Rushkoff: Well, the reason they're going down and their own fear are two different things. Their fear has been fueling them from the beginning. They're afraid of women. They're afraid of nature. They're less afraid of death than they are of life and complexity.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, that's a hell of a harsh assessment.

Douglas Rushkoff: The tech bros are deeply afraid of the very technologies they've made. They're afraid of AI because they think AI is going to do to them what they've been doing to us.

Brooke Gladstone: Got any proof for that assertion?

Douglas Rushkoff: They are the ones who are starting the big organizations and companies to prevent AI's domination. They think that there's a 50% chance, or 20% chance or 90% chance that AI will lead to the end of the world because AI will decide that human beings are unnecessary.

Brooke Gladstone: Some have suggested that's just a ruse so that Congress will hold the experts even closer because we need them so desperately to survive.

Douglas Rushkoff: Right. The most earnest among them actually either believe what they're saying or believe that they need to bring in government and regulation in order to help develop AI. The more cynical way of understanding it is they want regulation so that they can preserve their monopolies. The minute you bring in regulators, the biggest players at the table win. Another cynical response is that they're just trying to sell a technology that isn't really so special, anyway. These are just algorithms that, if you talk about them as, oh, these could end reality itself. Then it seems important.

Brooke Gladstone: Either way, you really think they're going down.

Douglas Rushkoff: Either the tech bros will go down or we all go down. This is not a way to sustain a civilization. Each time you turn the wheel of accelerationist capitalism, you have to pull that much more out of the planet every week. It goes back to why we can't just replace all of our oil cars with electric cars overnight. Where do you get the molybdenum? Where do you get the cobalt? The amount of mining we would have to do to get the rare earth metals defeats the laws of physics.

You can't keep growing. There is a fixed reality in which we live. The saddest part is the human project, the natural project. The species on the planet don't need economic growth, only this operating system needs economic growth. These tech bros, rather than questioning that basic economic operating system, they are addicted to it, stuck in it. They're willing to do whatever they can to keep growing that thing.

Brooke Gladstone: These guys have a doomsday plan which you think can't work, do you?

Douglas Rushkoff: I'd argue that the way to prepare for the event or to prevent the event are the very same things. So mutual aid, localism, meeting your neighbors, not being afraid, afraid of them. The story that I've been telling lately is when I had to hang a picture of my daughter after she graduated high school, I didn't have a drill. The first thing I thought to do, like any tech bro, is go to Home Depot, get a minimum viable product drill, use it once, stick it in the garage and probably never use it again. If I do, I'm going to take it out in two years, it's not going to recharge, and I'm going to throw it out. Or I can walk down the street to Bob's house and say, "Bob, can I borrow your drill?"

How have we, through digital technology, become so desocialized that we're afraid to ask our neighbor for a favor? Because what's going to happen? I'm going to borrow the drill from Bob, and then Bob's going to see me having a barbecue the next weekend and wonder, "Hey, Doug should invite me over for that barbecue because I just lent him my drill." Then I invite Bob over, and the other neighbors are going to smell the barbecue and think, "Why aren't we over there?" Then, before long, we're going to have a party with the whole block.

That's the nightmare. That's what the technologists are building their bunkers for. It's to get away from us and America, humanity, all of our natural resources. We're just the first stage on the rocket, the disposable stage that they can jettison once they've made it to the next level. I promise you, they're not going to make it. There is no next level. This is it.

Brooke Gladstone: Doug, thanks so much.

Douglas Rushkoff: Oh, thank you for having me.

Brooke Gladstone: Douglas Rushkoff is a professor at the City University of New York of Digital Economics and Media, and his latest book is called Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires.

Micah Loewinger: That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Callender, and Candice Wang.

Brooke Gladstone: On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.