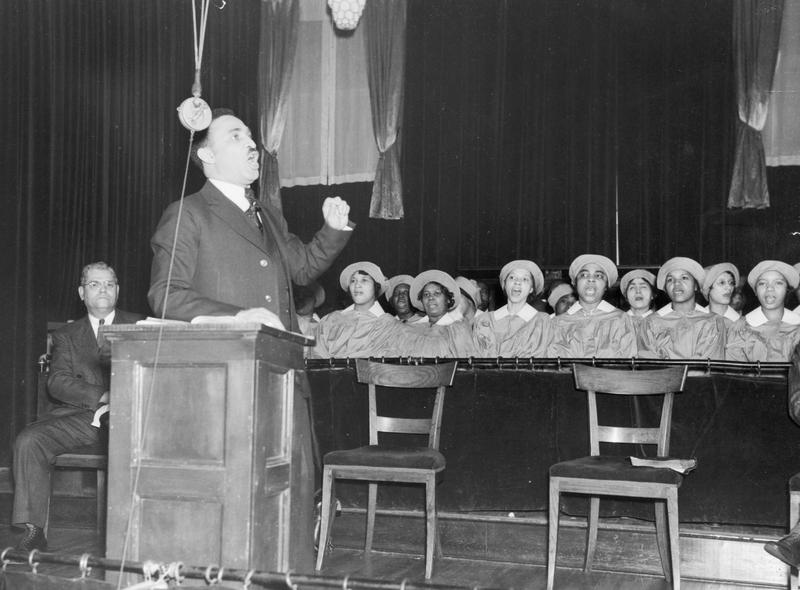

The Famous Black Preacher Who Feuded With MLK

( Getty/Bettmann / Getty )

Brooke Gladstone: This is the On the Media midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. For these final weeks of summer, we wanted to transport you away from the doom and gloom of the daily news with a trio of stories produced by our friends at the public radio documentary-maker, Radio Diaries. The series is called "Making Waves" and it profiles three people who pushed the boundaries of radio: one to warn, one to rile, and one to preach. What they had in common was that they were all controversial. They spoke to huge audiences in their time, and today, they're largely forgotten. Part one of the series is The Preacher.

In 1934, The Washington Post called Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux the "best-known colored man in America." His Sunday services were broadcast to over 25 million listeners on CBS radio. Black America saw Michaux as a leader for racial harmony and progress, but during the Civil Rights Movement, his reputation took an unlikely turn.

[archival soundbite]

Unidentified Announcer: Good morning from the nation's capital. From the Church of God in Washington, DC, we bring you now its regular Sunday morning service conducted by Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux.

Joseph Sturdivant: When I was a little boy and my father took me to the church, there were so many people in there, there was no seats.

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: You see the band, the choir, and then you see him waltz into the church and jump up on the pulpit. Then the choir starts singing Happy Am I.

[soundbite of song]

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: Then he would begin his sermon, and even as a child, you knew to be still and to listen.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Good morning. Is everybody happy? This is Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux, the Happy Am I preacher, come this morning to tell you Jesus loves you.

Joseph Sturdivant: My name is Joseph Sturdivant, and I've been a member of the Church of God since birth, 1933, and I'm still there.

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: My name is Lillian Ashcraft-Eason. I was born into the Church of God in 1940.

[soundbite of music]

There were other good preachers, but the Church of God made you feel special. People in the church thought that they could go to him with any problem that were bothering them within their lives. There was the Great Depression, for example, and a lot of people came to the church because they were hungry.

Joseph Sturdivant: The Happy-Am-I cafe was down on 7th Street. You could get a meal for 1 cent, and the interesting thing about that cafe was that we fed a lot of white people. He was always looking to do things that other preachers wouldn't do [laughs].

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: Your friends, your associates, were all members of the Church of God. That was your family. Elder Michaux was like your father.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: I'm not much of a singer, but I thank God for my song. I'm on my way rejoicing. I'm happy all day long.

Lerone Martin: He's known as the Happy Am I preacher, so he has this kind of charisma, smiling, very happy. My name is Dr. Lerone Martin, and I am the director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. He knows how to put people at ease, how to make people laugh.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: When the load get heavy and the way seems dreary, I just keep on singing my song Happy Am I.

Lerone Martin: There were many who ridiculed him. One detractor called it a religious version of Amos and Andy, but he also had a great deal of supporters.

Joseph Sturdivant: Sometimes, you would have busloads of people, white people, that would come from different cities just for that broadcast. It was unusual to have something like that going on.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Ain't no white, nor Black, brown, nor yellow, nor red with God. I said, I'd die for a white man as quick as I would for a Black man. God's grace is for every human race.

Lerone Martin: Michaux is someone I think that we can point to as a radio genius in the sense that he's able to do something that most of us could not imagine by having a nationwide broadcast that is extremely popular with both Black and white listeners, and this is an African American man in the early '30s.

[soundbite of music]

Suzanne Smith: He decides to support Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his first election to the White House and go on the radio and encourage African Americans to vote and really brings in a lot of votes for him. I am Suzanne Smith. I'm a professor of history at George Mason University, and I'm currently working on my book project on Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux.

Once he develops that relationship with Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower also see him in a similar vein. The presidents see him as someone who is a national voice that African Americans listen to, that if he endorses them in any way in his broadcasts, it will get African Americans to vote for them.

Lerone Martin: He ingratiates himself with these presidents, in many ways by flattery. He writes to Truman, and he says, you're God's man, and in fact, look at your name. Your name says, true man because you are a true man. He is a constant figure in the White House, even if he's being brought to the White House under the cover of darkness.

Joseph Sturdivant: Generally, Black people didn't go in the White House. My father-in-law was his chauffeur at one time, and he said, he would take him to the White House, but they would usually go there about two o'clock in the morning when nobody could see him going in there [laughs]. Whoever heard anybody do anything like that?

Suzanne Smith: He's very much a wheeler dealer.

Lerone Martin: He sincerely believes that having insider status is what's going to help people of color the most, not protesting power, but trying to work with power.

[archival soundbite]

Unidentified Narrator: Upon the shoulders of John Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI since 1924, rests heavy responsibilities. Not only must he direct the Bureau's offensive against subversive agents--

Suzanne Smith: He knew how to find favor with white people. That was his strategy throughout his life for trying to uplift his race. In the 1940s, he starts communicating with J. Edgar Hoover, and J. Edgar Hoover was tremendously revered by most Americans. They felt he was somebody who was fighting crime in America and fighting communism in America, and doing a good job.

Lerone Martin: Michaux says that I am a Christian. I know that the FBI is a Christian organization, and together, we can make sure that communism doesn't get a foothold in this country.

Suzanne Smith: Hoover is trying to cultivate his relationships with religious leaders to shore up support for his own investigative missions and his general power in the government.

Lerone Martin: Their relationship heats up after King's I Have A Dream address at the March on Washington in August of 1963.

[archival soundbite]

Martin Luther King Jr: Even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream.

Lerone Martin: Hoover is concerned about this. He believes that there is a communist conspiracy at root within the Civil Rights Movement and particularly with Martin Luther King Jr. That's the moment where the FBI is plotting and thinking that Michaux may be useful. They will call Michaux into service. Any time they need someone to launder information for them, they'll call in Michaux, and he'll do so on his radio broadcast.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Don't worry about them in Alabama or anywhere else. All of us are going to die, but what we want to do is we show. When we do die, we've got a home in the sky.

Lerone Martin: Michaux is saying, all this protest, all this nonsense, all this jostling for rights, is absurd.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Don't let malice or envy. Don't let the newspapers nor the radios stir you up. Just get on your knees and pray for them. Amen.

Lerone Martin: He goes about saying that racial equality is a worthy thing to pursue, but it's never going to materialize until God establishes his rule in people's hearts. Martin Luther King's dream is just silly. I do think Michaux sees King's rise in some ways as a threat. Not only is King rising to power, but he's getting recognition. At the end of 1963, he's informed by Time magazine that he's the man of the year.

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: He was trying to hold on to his members, and he didn't want them over there in the Civil Rights Movement. That was going to take them away from the church and maybe away from their membership. I remember feeling a conflict. There was the Civil Rights Movement. That was good. There was the Church of God. That was good. So how do you live with those two forces?

Joseph Sturdivant: When Martin Luther King made the speech, Elder Michaux told us that that dream was not going to come true in this world. Now, he wasn't against Martin Luther King. He didn't say that, but the Lord is going to have to work that out. There was more than a man could do. Elder Michaux told us that that was the way it was going to be.

[soundbite of music]

Suzanne Smith: He becomes increasingly marginalized because he stood up against King.

Lerone Martin: He was still on CBS, but the popularity did decline.

Suzanne Smith: Everything he had known in his life was being questioned when he was seeing a man like Martin Luther King, who was far more eloquent in many ways and far more confrontational.

Lerone Martin: You had entertainers of the day, popular entertainers of the day, who were coming out in support of civil rights. He didn't adjust. He stayed with the Happy-Am-I formula, and I think many of Americans at this time, especially Black Americans, began to not really enjoy the form. There are a number of letters to the editor in Black newspapers where people will criticize him and say, what is he doing? I've enjoyed his preaching, but you do not publicly attack Martin Luther King Jr.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: H.

Congregation: H.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: A.

Congregation: A.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: P.

Congregation: P.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: P.

Congregation: P.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Y.

Congregation: Y.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: A.

Congregation: A.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: M.

Congregation: M.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: I.

Congregation: I.

Suzanne Smith: Up until the last few weeks of his life, he maintains his radio broadcasts, and you can hear it in his voice that he's really physically not well.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: This morning, the world is standing in the need of prayer.

Congregation: Amen.

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: Every man, every woman, that knows that his hands are clean, heart pure.

Suzanne Smith: He eventually suffers from a stroke and is hospitalized. He passed away quietly in the hospital in October of 1968.

[archival soundbite]

Lightfoot Solomon Michaux: If I go away, I am coming back to receive you. All you've got to do is to keep on believing.

Congregation: [singing] Keep on believing.

Lerone Martin: People often don't want to acknowledge that he had such a popular following because his politics now, in retrospect, were on the wrong side of history.

Lillian Ashcraft-Eason: I think he's sort of forgotten. I wanted him to become more of an associate of Dr. King's, but I think that I understand that there are no perfect people.

[archival soundbite]

Congregation: [singing] Keep on--

Joseph Sturdivant: There's only one Elder Michaux. We just try to live according to the gospel that he preached. What he told us is still true. He's not here, but the gospel is still here.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Elder Michaux's sermons are still published in the Church of God's monthly bulletin, and the church still stands on Georgia Avenue just outside Washington, DC. The congregation is smaller now, but they still meet for services twice a month. The recordings of Elder Michaux you heard in this story were from the National Museum of African American History and Culture's Church of God Audiotape Collection. The story was produced by Mycah Hazel and the team at Radio Diaries. Special thanks to Sarah Kate Kramer.

Radio Diaries has been producing sound-rich, intimate stories for nearly 30 years, from their teenage diaries, where they gave teenagers tape recorders to document their lives, to the archival rich, hidden histories, like the one you just heard. Now, like everyone in public media, they're facing potentially disastrous funding cuts. Radio Diaries relies on federal funding for nearly half its budget, so it could really use your support. Visit their website, radiodiaries.org to help them out, and to listen to decades of incredible radio. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.