Revisiting a Conversation with Paul Auster

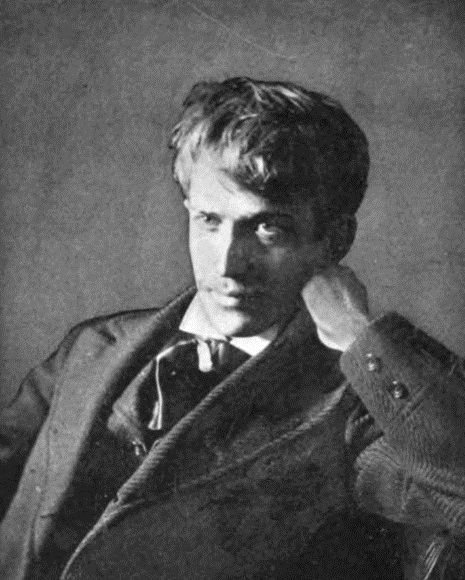

( Public Domain )

Micah Loewinger: This is the On The Media midweek podcast. I'm Micah Loewinger. Last week, news broke that writer Paul Auster had died from complications related to lung cancer. The New York Times called him "the patron saint of literary Brooklyn". Elsewhere, he was dubbed the dean of post-modernists. He was the author of many, many novels, including the seminal New York Trilogy, and he wrote screenplays, and memoirs, and nonfiction including Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane.

He was also a longtime friend of Brooke and her husband, Fred Kaplan. They lived a few blocks away from each other in their Brooklyn neighborhood. In November of 2021, Paul Auster walked over to Brooke's home studio to talk about Stephen Crane.

Brooke Gladstone: We've often practiced on this show the art of looking back to understand the present, especially the past that has been forgotten or nearly, and those who explored it and to find it likewise unremembered, like the writer Stephen Crane.

[music]

Paul Auster: Born on the day of the dead and dead five months before his 29th birthday, Stephen Crane lived five months and five days into the 20th century, undone by tuberculosis before he had a chance to drive an automobile to watch a film projected on a large screen or listened to a radio, a figure from the horse and buggy world, who missed out on the future that was awaiting his peers.

Brooke Gladstone: That's acclaimed novelist Paul Auster reading from his new book of nonfiction Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane. In it, he makes the case that not only did Crane miss out on his future, but we, his readers, missed out on the radical literature he could have written if only he'd lived longer. Before his death in 1900, Crane found enduring critical acclaim and a mass audience with The Red Badge of Courage, a Civil War novel he wrote at 23.

Paul Auster: Not once does he name the war. Not once does he say what the war is about. The word slavery is never mentioned. The name Abraham Lincoln is never mentioned. The name of not one general is ever mentioned. We don't even know where we are. We're in a kind of haunted space inside the mind of a 16 or 17-year-old boy.

Brooke Gladstone: That's the book that most of us who can remember Crane know him by. Auster read it in high school but when he returned to Crane's work decades later, he found a captivating corpus, vast in size and impact. To pay his constantly mounting bills and debts Crane produced reams of mostly journalism, vivid fly-on-the-wall accounts of people reckoning with poverty, natural disaster, war. Crane also wrote poems. I asked Auster to launch our talk by reading this one.

[music]

Paul Auster: In the desert, I saw a creature, naked, bestial, who, squatting upon the ground, held his heart in his hands, and ate of it. I said, "Is it good, friend?" "It is bitter, bitter," he answered. "But I like it because it is bitter, and because it is my heart."

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Let us begin close to the beginning with Maggie because this sets him on his path what is it that Stephen Crane originated? I think it's fair to say that a big part of that starts with Maggie.

Paul Auster: Well, it's true. Maggie is his first novel. It's really a novella. He wrote it when he was 20 and the early months of being 21. It's a book set in the slums of New York City in an imaginary neighborhood called Rum Alley or Devil's Row. It's about an impoverished family, a rough hard-drinking family.

[music]

Paul Auster: Maggie broke a plate. The mother started to her feet as if propelled, "Good Gawd," she held. Her eyes glittered on her child with sudden hatred. The fervent red of her face turned almost purple. The little boy ran to the halls, shrieking like a monk in an earthquake.

[music]

Paul Auster: The central character of Maggie is, through a series of misadventures with a loutish young man, is reduced to walking the streets as a prostitute and eventually dies. It's not so much the subject that is so astonishing about this book. It's the vividness of the writing, and it is also Crane's refusal to moralize, which was the standard approach of any writer of the day writing about the poor. It had to have uplift. It had to have hope. It had to offer solutions to making the world a better place.

In any case, Crane's first writing experiences were as a journalist. He had the good fortune to have an older brother 19 years older than he was, who owns a news agency. Crane as a teenager was working for his big brother, Townley, doing little tidbits for the summer season in Asbury Park, which was the most thriving seaside resort on the East Coast at the time. It was a great place for Crane to learn his trade.

This journalistic neutrality carries over into the fiction he wrote, therefore, no judgments. This was so shocking that every publisher in New York rejected it. He was reduced to having to publish the book himself by scraping together the money of his inheritance, which wasn't very much. Even the printer was so shocked, they refused to put their name on it. Members of Crane's own devout Methodist family hid their copies in the attics of their houses and eventually burned them.

Brooke Gladstone: You say that in his lack of judgment and his attention to detail, he actually prefigures people like Camus or Joyce, others?

Paul Auster: Hemingway was very influenced by Crane. Yes, Crane is the one who opens the door onto a new sensibility.

Brooke Gladstone: He was a rebel with regard to his own family, and he referred to himself as the black sheep.

Paul Auster: He rebelled against this hypocritical piety. The great thing that drives all of Crane's work was to be honest, not to tell lies, to actually explain and describe and tell stories about the real world, but he's not a realist in the strict sense of the word. He's not Zola, with that tedious long-winded, over-detailed realism. No, no, no. This is why I say he's the first modernist. Crane's approach to telling stories was to strip out everything that wasn't absolutely fundamental to his purpose. All the tropes of the traditional 19th century novel and the beautiful things that we all love so much, Crane got rid of it all. As I say somewhere, yes, you can curl up on a sofa with a Tolstoy novel. You have to read Crane sitting bolt upright in your chair.

[laughter]

Brooke Gladstone: You describe Crane's writerly tone in Maggie as reminiscent of a war correspondent who steadily surveys carnage as it unfolds. Of course, Crane would later report on war for a variety of newspapers, you've ignited a discussion about whether Crane was a journalist.

Paul Auster: This was the golden age of newspapers. In New York City alone, there were 18 daily papers published in multiple editions every day, with elaborate full-color Sunday supplement. In addition to those, there were 19 foreign language daily papers. The press was everywhere and the press needed, well, as they say today, content. There were many more kinds of writing that appeared in newspapers then than is the case now.

Brooke Gladstone: Paul and Twain both wrote in papers, and they both put in stories that were completely fictitious. [chuckles]

Paul Auster: Yes, but newspapers also published overt fiction and they published poetry. Then there was a form, and this is the one that Crane excelled at, called the sketch, which shares traits of traditional reportage and fiction writing. Often the lines blur so much that you can't tell. Crane throughout 1894 was writing many of these sketches, and they're marvelous pieces, about all kinds of things going on in New York City. There was a tremendous economic depression going on then, the panic of 1893. He wrote The Men in the Storm, it's a great piece of work about unemployed men waiting to get inside a shelter for the night.

Brooke Gladstone: In The Men in the Storm, he came back the worse for wear after going and joining those people who were trying to get into the shelter.

[music]

Paul Auster: Some of the gusts of snow that came down on the close collection of heads cut like knives and needles. The men huddled and swore, not like dark assassins, but in a sort of an American fashion. Grimly and desperately it is true but yet with the wondrous under-effect. Indefinable and mystic as if there was some kind of humor in this catastrophe.

[music]

Paul Auster: Yes, because he went out into a February blizzard without an overcoat. He might not have had an overcoat then. He was so poor.

Brooke Gladstone: A friend said, "Why didn't you just put on a few extra undershirts?"

Paul Auster: Crane said, "How would I know what those poor devils were feeling if I didn't feel it myself?"

Brooke Gladstone: He observed that there were two kinds of mostly men waiting outside for the shelters, the temporarily unemployed and the habitually unemployed. Their views of the world differed enormously.

Paul Auster: Yes, the unemployment rates in New York City were staggering. I think it was 30% were unemployed here. He talks about the recently unemployed men. He says that the men are not angry at the rich nor at the poor. They're just bewildered where they went wrong to have lost out in the game. This sense of personal failure in the capitalist battleground that America has always been is very deep comment for someone that young to be able to make. This is the same attitude that one felt during the next Big Depression, even bigger in the 1930s, and explains it seems to me why America has never had a socialist revolution.

The workers' movements in America, and there were violent strikes all through Crane's lifetime, they didn't so much want to overturn society, they just wanted a fair shake at doing well in the established society that had been set up. It's a very different attitude. It's not a revolutionary one, but an evolutionary one.

Brooke Gladstone: You observed that a contemporary reporter witnessing a scene similar to the one that Crane observed in 1894 would have cited unemployment rates and included statements of experts and so forth, and he didn't. He just sat down and watched and listened. This sketch featured the kind of observation that even a mountain of data could not have provided.

Paul Auster: He didn't even go inside. He didn't talk to anybody who worked there. A journalist today would be obliged to do that and count how many beds there were. What kind of services did they provide? Where was the money coming to fund it? How many people did they have every week, every month? None of that. He just stood because it was too cold to sit. It was a foot and a half of snow. He just stood there and watched and listened. Then he walked home, he sat down and wrote a seven-page piece after all that and collapsed in bed. It's a remarkable piece of writing but, again, it does not conform to what we would call journalism today. It irritates me a bit when people say Crane learned everything about how to write fiction from being a reporter. He was never really a reporter.

Brooke Gladstone: Spoken like a true novelist.

Paul Auster: Yes. [chuckles]

Brooke Gladstone: Then there's the story, The Open Boat, would you call a documentary fable. In it, he writes about his experience of being shipwrecked. This piece, you say and he said changed him.

Paul Auster: Oh, definitely. The shipwreck happens before the story begins. What we are is in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Florida, in a little 10-foot rowboat, a dinghy.

Brooke Gladstone: He describes how the boat pranced and reared and plunged like an animal. As each wave came, she rose for it. She seemed like a horse making it a fence outrageously high.

Paul Auster: This ship has sunk. There had been 20 men on board, seven of them drowned. Crane was stuck out there. In this story, he calls himself the correspondent.

[music]

Paul Auster: There was this comradeship that the correspondent, for instance, who had been taught to be cynical of men, knew even at the time was the best experience of his life. But no one said that it was so. No one mentioned it.

[music]

Paul Auster: The somewhat hard-boiled, suspicious, sometimes cynical Crane had a transformative experience there. Just to sum up his approach to the world is that the gods have vanished. We live an absurd, meaningless cosmos. It's not as if nature is cruel, nature is just simply indifferent. This could lead to a nihilistic position about things. If nothing matters then why be good? [laughs]

What his work tells us is that he says, "No. What human beings do with and among one another counts for everything. Even if we mean nothing in the cosmos, we are the measure of all things for ourselves. We can create extraordinary moments of cooperation and solidarity that give life meaning, or we can divide, go at each other and make life hell. I think this is the push-pull conflicts that he's dealing with, particularly in the last years of his writing life. This position is very close to Camus. It is existentialism before the fact.

Brooke Gladstone: The story, The Open Boat, reminded you of one of Crane's poems. A man said to the universe, "Sir, I exist." "However," replied the universe, "The fact has not created in me a sense of obligation."

Paul Auster: [chuckles] That's Crane's wit at work too. He could be so deadpan ironic when he chose to be.

Brooke Gladstone: It was such a struggle and not just with his health, but with his finances and the stress of it you convey incredibly well, Paul. Let's talk about the society of his final days. Our listeners, some of them may not know Crane's name, but they are far likelier to have heard of his close friends Joseph Conrad, Henry James. He was friends with H.G. Wells and Ford Madox Ford, not to mention, obviously, his erstwhile fans and frenemies like Teddy Roosevelt and William Randolph Hearst. Why do you reckon Crane has been mostly forgotten while the other writers from his day are more read and remembered?

Paul Auster: The answer to that question is simply that he lived such a short life. He was a comet who flashed across the sky, and then he disappeared. He never gained a real toehold in the literary world. All of these other writers lived reasonably long lives, and they had time to develop, time to establish themselves in their different cultures. Henry James, he never sold that many copies of his books. He was not a popular success. James' real success has come in the many years following his death. Now he's considered a master. Then he was considered an interesting writer, but a little stuffy. [laughs]

Wells, we don't need to talk about. He wrote all his most famous science fiction books then, during the period when he knew Crane. Conrad struggled terribly in the beginning, just as badly as Crane had but, eventually, of course, he became recognized. Crane fell in love with Conrad's work, and he understood that Conrad was a spiritual brother. Conrad was overpowered by Crane's work. These two became the closest of close friends. Conrad worked, I think, for the rest of his life, with a photograph of Crane on his desk. Conrad wrote very movingly about his friendship with Crane.

The story he tells, I mean, Crane was so weak, he could barely talk, he was in a bed overlooking the sea. He just said, "I'm so tired." Conrad just stood there in the door looking at Crane, who was looking out the window at a boat passing by.

Brooke Gladstone: You make reference all through the book to things that Crane did first. The lack of moralizing dialogue that in one story you liken to Raymond Chandler, the sort of beginnings of, is it fair to say stream of consciousness? Following the thoughts inside of a head during a time of great stress so many things that were later done and, I think credited in the popular imagination to others, one thing that you note was that his unique ground on which he wrote was coherence and a blur.

Paul Auster: I'm glad you brought this up because it's a fascinating moment in his work. If one really wants to understand Crane, one must read the journalism, whatever, however you want to define this journalism, because some of the most pertinent statements he made are buried in these pieces for newspapers. Crane left the city for a day to write a piece for Pulitzer's World on the electric chair at Sing Sing, and it's called The Devil's Acre.

Crane goes out and visits the graveyard in which the dead prisoners have been buried. There's a house at the edge of this graveyard overlooking the Hudson River. He simply writes this, "If people on this veranda ever lower their eyes from the wide river and gaze at these tombstones, they probably find that they can just make out the inscriptions at the distance and just can't make them out at the distance. They encountered the dividing line between coherence and a blur."

Now, I think this is an extraordinarily perceptive remark that line that Crane inhabited as a writer, and I think he's the first one to discover this territory and stick it out as his own.

Brooke Gladstone: What do you imagine he might have done had he lived beyond the age of 28?

Paul Auster: It's the inevitable question that one can't help but ask and fully understanding that there's no answer to it. It's impossible to say. If he had followed his best instincts and impulses as an artist, if he hadn't been crushed by poverty, assuming that he was still on his feet, assuming that his vision hadn't been corrupted what he was going towards is writing in the first person, which is something he really didn't do. Except there's a piece that he wrote in the last year of his life called War Memories. It's over 40 pages, so pretty long for Crane. It's written in the first person and it's about his experiences in Cuba.

I think for the first time in a text, all sides of Crane are present almost simultaneously, humor, and it's very funny at times, but also the dark, even tragic things that he encountered there. The voice is so vibrant, that I think if he had lived, I think he might have found another avenue to express himself through these first person narratives. I speculate that it's fascinating because early on his position is so rigorously third person, defiantly third person. I am the invisible fly on the wall but, no, he's feeling more comfortable about himself. He's still not even 30 years old and he's starting to get his feet on the ground, so who knows?

Brooke Gladstone: From the moment the reader encounters him, he seems to know his time is running out. I wonder if that affected the nature of his work.

Paul Auster: I think it did and I think it affected the nature of his life as well, which would account for his tremendous risk-taking and his great love of gambling. The early years of his life, he was sick a lot. I think he started talking about how he wasn't going to live long when he was as young as 20. Knowing that, in terms of the work, that his writing gravitated towards essential questions. Most of his great work is about people in extreme situations, whether it is crushing poverty, war, physical danger. That's why the work doesn't get old because these things don't change in human life.

He can write as well as anybody ever wrote what goes through your mind when someone's pointing a gun at you, and you think the trigger is going to be pulled within the next 15 or 20 seconds. 1890 or 2021, it's just the same experience, and therefore I think his work is eternally relevant. That's why I wrote this book [chuckles] because my sole aim was simply to get people to start looking at Crane's work again.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much, Paul.

Paul Auster: Brooke, it was a pleasure to do this with you.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: Paul Auster died last week at the age of 77. Thanks for listening to this week's midweek podcast. On the show this week, I'll be examining some of the enduring media tropes of campus protest coverage. See you Friday. I'm Micah Loewinger.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.