Goodnight And Goodluck 20 Years Later

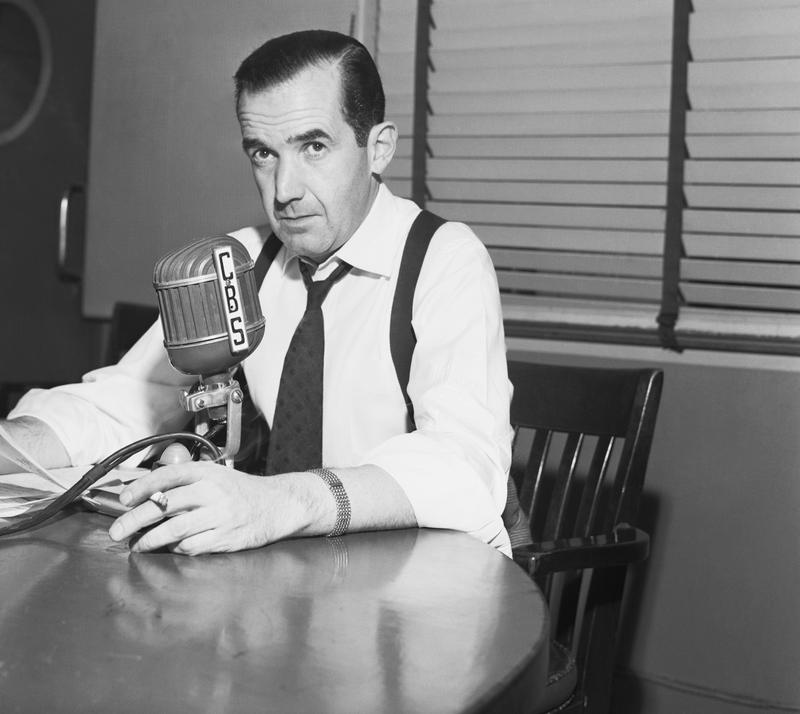

( Bettmann / Getty Images )

[music]

Micah Loewinger: Hey, you're listening to the On the Media Midweek podcast. I'm Micah Loewinger. As we've talked about in recent episodes of the show, there are big things happening over at CBS News. The network was purchased by a company controlled by the Trump-friendly Ellison family, who quickly installed an ombudsman who seems likely to toe a politically right-leaning line and who are considering hiring Substack flamethrower Bari Weiss as head of the news division. It's all a far cry from the network's heyday, depicted in the 2005 movie, Good Night and Good Luck, which tells the story of Edward R. Murrow's heroic stand against McCarthyism.

Joe and Shirley Wershba were at CBS then. In the movie, they're played by Robert Downey Jr. and Patricia Clarkson. It was Joe who, in 1953, interviewed Lt. Radulovich, the man kicked out of the Air Force Reserve because his father, an immigrant from Serbia, subscribed to foreign newspapers and because his sister supported liberal causes. The New York Times noted that it was the first salvo fired by the network against Senator Joe McCarthy. Brooke spoke to Joe and Shirley about the film when it was released 20 years ago and about the bygone days of smoke-filled newsrooms and courage on the airwaves.

Brooke: Joe, Shirley, welcome to the show.

Shirley: Thank you for having us.

Joe: Thank you.

Brooke: This is one evocative film. It's shot in black and white and, of course, in early 1954, McCarthy's hearings of accused subversives were broadcast. They were the first ever televised hearings, and they were used in the film. McCarthy essentially plays himself. Murrow, of course, couldn't be depicted by recycling old TV footage, so they have an actor to play him. You knew Murrow. How accurately do you think he was depicted in the film?

Shirley: If you closed your eyes during the first read-through of the script? I did close my eyes, and I thought I was hearing Murrow.

Edward R. Murrow: We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law.

Shirley: It was unbelievable.

Joe: I'll tell you how unbelievable it was. When I first saw Strathairn, I saw him from the back of his head, and I said, "My God, it's Murrow's head." The minute he opened his mouth and looked towards us, it was Murrow all over again. He didn't try to imitate Murrow, he exuded Murrow.

Brooke: George Clooney plays the legendary Fred Friendly as a relatively quiet, wry person. He was Murrow's producer. He also functioned, in some degree, it seems, as his heat shield.

Joe: Fred Friendly was the enforcer. Murrow came up with what he wanted to do with the line that he was taking, and Fred saw to it that all the stuff that we had was edited with that in mind. If anybody ever terrorized people, it was Fred.

Shirley: I think he wanted Murrow to have all of the attention.

Brooke: One thing I noticed was that during Murrow's broadcasts, we see Fred Friendly literally crouched at his feet, obscured partly by his desk, and he cued Murrow by tapping a pen on Murrow's knee. He lit Murrow's cigarettes during the tape segments, speaking quietly, still crouched there. Was that what it was really like?

Shirley: Yes, exactly. That was the way he cued Murrow to start because they were in very, very tight quarters. As a matter of fact, some of the people who saw a screening of it, people like Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather, Morley Safer, and Walter Cronkite, they said they have never seen a newsroom film that was as authentic as this.

Brooke: Cigarette smoke seems to fill nearly every frame, mostly coming from Murrow's cigarette.

Shirley: Everybody smoked in those days. I smoked, Joe smoked.

Joe: At a time when we went to Korea to cover the Korean War in '52, Ed and I shared a room, and at 4:30 in the morning, I would hear zip. That was Murrow starting his morning with a cigarette. He was doing a minimum of two packs a day, but I think he went up to four packs a day.

Shirley: Yes, he always had a cigarette.

Joe: He just couldn't be talked out of it until he developed lung disease later on.

Brooke: He died of lung cancer in 1964.

Shirley: Yes, he did. The interesting thing about the crew of actors in the scene is that I don't think any of them smoked, and here, they had to. I know they were not inhaling, they were just bubbling it out. When George Clooney learned from Ruth Friendly that Fred Friendly had never smoked, he was so relieved because he's not a smoker. He didn't have to smoke, but everybody else did.

Brooke: I want to move to the political environment now. I'm talking about politics with a big P and politics with a small P. In terms of office politics, there was a rule that professional colleagues at CBS weren't allowed to marry.

Shirley: You weren't allowed to be in the company if you had a relative there, whether it was a cousin, an uncle, a sister, and certainly you couldn't be married.

Joe: Well, what's a fancy word for that kind of a situation?

Shirley: Nepotism.

Joe: Well, that was supposed to be nepotism at $45 a week, and it was a big word to spread over $45.

Shirley: We knew that one of us would have to quit. As a matter of fact, the boss at the time said he thought that we ought to get married. I said, "Well, we would, except I don't want to quit working." He said, "Well, don't tell anybody about it. I'll try to clear it with personnel," which he never did, so we had to keep it a secret.

Brooke: Did you really take off your wedding rings before you went to work?

Shirley: Absolutely. Joe actually didn't wear one, [laughs] but I put it on a gold chain around my neck. I always had high-neck blouses.

Brooke: Let me move on to William Paley. He ran the CBS network for what, about 50 years?

Shirley: Well, he started it.

Brooke: He's depicted by Frank Langella as a figure who is as huge and immovable as the Washington Monument. What role did he play in the real-life drama?

Joe: Bill Paley created the Columbia Broadcasting System. He backed the best news and news people that he could find. Murrow was his boy-

Shirley: And his friend.

Joe: -and his friend. It was a rarity for anybody to be Bill Paley's friend who wasn't a member of the family.

Brooke: Okay, but we see in the film a rather testy exchange between Murrow and Paley.

Joe: It got to that stage only because Murrow and Friendly were not going to quit cold on the stories that they did. Paley knew that they weren't going to quit. I thought that that was a fair shake that somebody should know that going on the air with an attack on McCarthy, this was breaking the rule which Paley and Murrow themselves had set up, which could lead to closing down the whole news business.

?Bill Paley: Somebody's going to go down. Have you checked your fax? Are you sure you're on safe ground?

?Edward R. Murrow: Bill, it's time. Show our cards.

?Bill Paley: My cards, you lose, what happens? Five guys find themselves out of work. I'm responsible for a hell of a lot more than five goddamn reporters. Let it go.

Joe: You could tell that a lot of the people were worried stiff about what the consequences of this program would be. Murrow caught and said, "Terror is right here in this room." Then he followed up with another line, which unfortunately is not in the script, but I remember it, and I couldn't have made it up myself, "No one man can terrorize a whole nation unless we are all his accomplices."

Brooke: You know, in the end, it wasn't politics but bottom-line pressures that compelled Paley to act and essentially push Murrow off of his primetime perch.

Shirley: Well, you know Paley, I think he once said his sorriest day was when he went public with the company because then, he had to answer to the economic pressures that would come from shareholders. You had to turn a profit. I think Paley, given his druthers, would have gone along with Murrow all the way.

Brooke: You two have, in the film, an exchange in bed one night. It's of such critical, dramatic significance I thought it was added by the writers. Joe, you muse, "What if we, we meaning Murrow's boys, are wrong. What if there are communists out there poised to take down our government?" You said, "What if we're protecting the wrong people?" Did that exchange happen?

Shirley: Not really.

[laughter]

Shirley: We talked about not so much were we wrong, but were we doing the right thing, because we grew up in this atmosphere of, "You don't take sides, you just present the news straight." That was the discussion that Joe and I used to have, "Should we break with it?" I can remember that thought in particular, "You've got to do it. You got to go with this program or else what happens to the country?" Also, he did offer McCarthy equal time to answer.

Brooke: Some say that the wise deadpan news anchor of old is passing out of time. Some of them see this as the model of the Murrow tradition, but actually, if you look at the film, Murrow wasn't the very model of the objective opinion-free anchor. His legend is built on when he took a stand. Nowadays, that would be seen as questionable journalism. I don't think he'd last long in the anchor chair.

Shirley: Well, he wouldn't be doing it every night or every week. It was on very, very special occasions. If you recall, Walter Cronkite stepped out behind that wall of impartiality when he said the Vietnam War was unwinnable. On rare occasions, if someone you respect who has been impartial, if he or she should say, "There is only one side here, I will give it to you," and then it's up to your audience to make the decision.

Joe: I must tell you that Murrow agonized over what right did he have to use the whole power of a network to go against one man. The answer to that is, "He, that man is strong enough to take care of himself." That's where that line from Shakespeare comes in.

Edward R. Murrow: Earlier, the Senator asked, "Upon what meat does this our Caesar feed? Had he looked three lines earlier in Shakespeare's Caesar, he would have found this line, which is not altogether inappropriate. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars the fault, but in ourselves." No one familiar with the history of this country can deny that congressional committees are useful. It is necessary to investigate before legislating, but the line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one, and the junior senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly.

Shirley: Right after he came out of the studio having done the McCarthy broadcast, I knew I was going to be having children, and I said, "Ed, if it's a boy, I'm going to name him after you." He answered, "Do you think it was worth it?" I said, "It has to be."

Brooke: Did you name your child after him?

Shirley: I did.

Brooke: You guys didn't take your work home?

[music]

Shirley: We lived our work. [laughs]

[laughs]

?Edward R. Murrow: Whatever happens in this whole area of the relationship between the individual and the state, we will do it ourselves. It cannot be blamed on Malenkov, or Mao Tse-tung, or even our allies. It seems to us, that is Fred Friendly and myself, that this is a subject that should be argued about endlessly.

?Micah Loewinger: Joe Wershba died at the age of 90 in 2011. Shirley Wershba is 103 years old. Thanks for listening to the Podcast Extra. Don't forget to tune into the big show this weekend when we'll observe that there's been a recent uptick in people being deemed terrorists and also martyrs. In the meantime, consider following the show over on Instagram, TikTok, and BlueSky, just search 'On The Media'. See you Friday. I'm Micah Loewinger.

[music]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.