Having a Child in the Digital Age

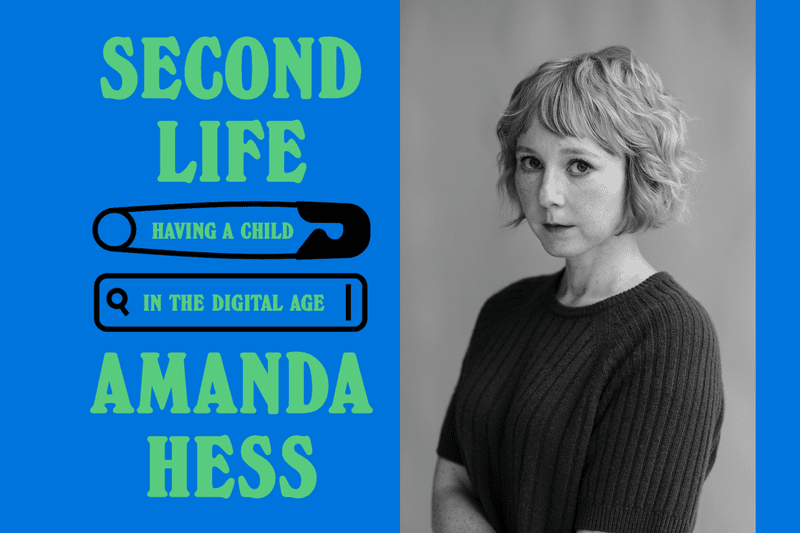

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media's midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. I recently became a grandparent, and I will say watching from the proverbial sidelines, pregnancy and the early days of parenting look very different from what I remember. There's a lot more information available and a lot more technology involved. That's the subject of Amanda Hess's new book, Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age. Our producer, Molly Rosen, could relate. I'll let her take it from here.

Molly Rosen: So there's a reason that I am doing this interview and not one of our hosts, and that's because I just had a baby nine months ago.

Amanda Hess: Oh, my gosh.

Molly Rosen: I either recently experienced or am in the midst of some of the things that you write about in your book. I really felt like your book helped me process some questions that I did not even know would arise for me. You have written for many years about the Internet and pop culture, and this book is a lot about how various technologies mediated the experience of your pregnancy and birth, and parenting. When did you decide that there was a book here?

Amanda Hess: I think I have been writing about the Internet for such a long time, and I have this relationship with it where I have a critical distance to the things that I'm investigating. It's very routine for me to look into something that's happening on the Internet and maybe join into a community for a little bit and then leave and leave it behind emotionally, too. It was immediately when I got pregnant that I realized that that was not going to happen this time.

I just had a very different relationship where the critical distance was completely gone. Just because I'm so used to it, I started taking screenshots and notes of things that I was seeing related to pregnancy online from the very beginning. Then when I was seven months pregnant and I had an abnormal ultrasound and I realized that my pregnancy was less than normal, I had this feeling, this intense superstitious feeling that by taking notes on my experience and writing little jokes to myself about how funny maternity wear advertising is, that I had doomed my pregnancy in some way.

This very powerfullly, superstitious feeling. I'm not a superstitious person. Then it was clear to me that I was not going to be writing about this experience. Then it was only later, after my son was born, that I realized that this feeling of superstition and this just sub rational part of me that was driving so much of my interaction with the Internet was actually really interesting to me, and I should try to find out more about why I felt that way.

Molly Rosen: Yes, that's so interesting, because I feel like I hear you saying that you almost had your critic hat on at first, where some things were maybe funny or unusual, and then it got very real, but that almost made it more worth exploring and writing about.

Amanda Hess: Yes. I also felt like I've done a bunch of stuff on the Internet that maybe is less than productive for myself. Just wasting time trying to solve like a plane crash from 15 years ago, or more seriously, trying to lose some weight and getting a little bit obsessed with an app that shows the jagged line of my body, trying to approach this straight line of my goal weight or whatever. I always felt like the only person I was really hurting was myself. Immediately when I got pregnant, I was like, "I'm now using these tools to bring another person into the world." I think that also forced a reckoning for me in trying to understand better how I was internalizing some of the messages from those apps.

Molly Rosen: I do want to ask about one of the apps that you used pre-pregnancy and then during pregnancy, which is a period tracker app called Flo. It's very popular, and when you became pregnant, it switched into pregnancy mode. How did your relationship with the app evolve over the course of your pregnancy?

Amanda Hess: When I first downloaded Flo to track my period, it presented itself to me as this girl power app that's for learning about yourself and empowering yourself through knowledge of your body. It's very feminized in its presentation. It looks like a preteen diary. I found it very helpful, actually. I didn't think at the time that I downloaded it that it would also transform through pregnancy mode. It makes it so clear that it's gamifying a pregnancy.

Immediately when I activated pregnancy mode, I just had a completely different experience with it. The interface was so different. It had turned from this kind of empowering diary into a disciplinary program, something that would tell me what I should be doing every day or every week, and then show this visualization of my progress through a CGI image of a stock pregnant person whose belly is expanding and a CGI image of this cell floating in nothing, and then a blastocyst and an embryo and a little shrimp-like being, and then like, a little peach baby doll that represented my child.

I think the thing that I never could have explained to myself before, and it's difficult for me to even understand now that I'm not pregnant anymore, is that when I looked at that janky image of a fetus, I felt like I was looking inside my body. It felt like it was really a true representation of my pregnancy. When, of course, it's just this cartoon that's generated for tens of millions of people who activate pregnancy mode through the app.

Molly Rosen: You did some research, actually, into how we got those images. What did you find when you looked into it?

Amanda Hess: What I found was that there was a Swedish photographer, Lennart Nilsson. He took a photograph that was put on the cover of LIFE magazine in the 1960s that purported to be the first photograph of a fetus at 20 weeks gestation. It was presented as if it was an eye inside of womb. I went on eBay and I ordered a copy of this fetus. The fetus looks much like the flow fetus in that it's a very ethereal photograph. There's this black, sparkly background as if the fetus is in space and is shrouded in some membranes. The fetus is styled as if it's its own planet floating in space.

Only when I looked inside did I see this caveat editor's note that said that this was not a living fetus. It was a fetus that had been surgically removed from its mother and then photographed afterwards. I mean, it was a picture of abortion material. That picture, even though it showed a fetus that was not going to be born, that had not been born, was then used by anti-abortion activists to show, purportedly, what a pregnancy looks like at various points of gestation in order to argue that abortion should not be legal.

Molly Rosen: There was a Federal Trade Commission complaint filed against Flo in 2021 regarding its handling of sensitive personal information. Obviously, a period tracker app, it's very personal information. I'm curious, after your reporting, what are your thoughts on the use of these apps and the potential privacy implications?

Amanda Hess: There is a lot of concern that data from a period app or a pregnancy app will be used explicitly in a case to criminalize an abortion or a miscarriage or a stillbirth or something like that. When I spoke with lawyers who defend women in pregnancy criminalization cases, they told me that they had not seen a case where that had happened yet.

I think what is obvious to me just from using the app, even if we don't know exactly how this data is being used, is that a consumer surveillance app functions to get us used to this idea that there ought to be an outside authority that is tracking and monitoring a pregnancy or even a menstrual cycle, and that this is a good and necessary thing, and that our bodies must be controlled and datafied in this way in order to have an optimal pregnancy or an optimal birth. I'm much more interested in the cultural habits that might emerge from the widespread use of that technology.

Molly Rosen: Yes, you write that advertising on Instagram became so personalized that it started to feel intimate. What did you find through your reporting about how many trackers were interested in the data about your pregnancy, and about how much that information was worth.

Amanda Hess: Immediately after I got a positive pregnancy test, I searched what to do when you get pregnant on Google, and a WebMD link popped up. What I was not aware of was how embedded in the online advertising ecosystem WebMD is. I then later went back and retraced my steps and found that when I searched for that again and went back to that WebMD page, that action had allowed 74 ad tracking companies to track me and stored 153 cookies in my browse,r and also sent that information to Facebook. About 24 hours after I made that search, when I was just staring at Instagram, I started seeing my ads turn into prenatal vitamin ads, maternity dress ads.

A lot of the times when a tech company is accused of using sensitive data that has to do with menstruation or pregnancy, they'll say something like, "There's no part of our backend that's tracking who is and who isn't pregnant," but there really doesn't have to be, because the systems are complex enough and automated enough that it just knows that if you search what I searched, you may be more interested in prenatal vitamin ads than someone who has not searched for that and ended up on the I just got pregnant page on WebMD.

Molly Rosen: Something that I think you did, which I also did, which I felt very clever doing, even though it's probably completely useless, was when I'd sign up for stuff and it would ask me for my due date, I would lie about the due date. What I thought was funny was you actually looked into how much that information about your pregnancy and your due date was. You write that, "My pregnancy was about as valuable as a list of CBD buyers suffering from OCD, a list of booming boomers with erectile dysfunction, and less valuable than a list of people who had purchased a Donald Trump-themed chess set, and a list of medical geneticists." You came to the conclusion that the value of this data was 1/10th of $0.01, almost worthless.

Amanda Hess: When we talk about how valuable the knowledge of a person's pregnancy is to add systems, there was a part of me that when I heard that, I was a little bit like, "Ooh, I'm in such a valuable state right now." It was a little bit flattering. The actual money that's changing hands, it's so meager, and the actual fact of the day that your baby is going to be born, which to me was the most interesting piece of data that my body had ever produced.

This idea of when might a baby come out of it is to them actually very, very, very cheap and just sold by the thousand. A lot of my book is encountering these technologies and feeling that they're so intimate and tailored to me and that they make me feel special. Then, looking at the back end and understanding that these companies don't care about me or my pregnancy, I'm not special to them at all. I'm like one of thousands or hundreds or hundreds of millions.

Molly Rosen: You open your book with a pretty intense scene. You're lying on an exam chair in the doctor's office, and your routine ultrasound is going suspiciously long. The technician keeps taking images, and you can tell that they've seen something that they want to look into. This starts you on what you call a diagnostic odyssey. Trips from one medical specialist to another. Could you walk me through how this experience unfolded for you?

Amanda Hess: Yes. I mean, I was lying there on the table, and every time this had happened previously in my pregnancy, there was a little voice of worry that was like, "What if something's wrong? What are they going to say?" Every time it was completely normal, and this time it wasn't. It felt like this thing that I had long feared was coming true. The thing that I remember the most about being on that table, my husband wasn't there because this was 2020, and so guests were not allowed in an ultrasound room. My first thought wasn't, "I wish my husband was here." My first thought was, "I wish I had my phone with me here so I could start Googling these things that I'm seeing the technician investigate on the screen." Then once I did seize my phone, I seldom let it go.

Molly Rosen: You wrote that if I had the phone, I could hold it close to the exam table and Google my way out. I could pour my fears into its portal and process them into answers.

Amanda Hess: Yes. Eventually, when the doctor came in, he told me that my son was sticking out his tongue on the ultrasound persistently, which is unusual, and that he suspected that it might be a rare genetic condition called Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, which now I'm very familiar with, because he was right, and my son does have that. At the time, all I heard was that unrecognizable German name syndrome. It was incredibly scary. It took a full month to confirm that that's what it was.

In between, there were many theories, some of them catastrophic, about what was actually going on. Later, what I really came away with from that experience was I'd started in the pregnancy Internet, so centered in its image of what a pregnant person in a pregnancy is supposed to look like. White, able-bodied woman who has enough money that maybe she'll buy a gadget to put in her nursery, so we're going to pay a lot of attention to her. Then this image from Flo, that was just stock fetus. It was only after I had that ultrasound that I realized, of course, Flo's stock image did not look like my son looked on an ultrasound.

This other pregnancy Internet zone that I had entered was one that acknowledged disability, which the generic pregnancy Internet really did not. I felt like I had been cast out of the normal pregnancy Internet that had spent seven months trying to get me to feel like it was my community. At first, that felt awful, and later, I now think of it as such a gift to have this opportunity to see all of the assumptions that it had been making all along that didn't apply to me, and frankly, do not apply to anyone.

Molly Rosen: You write about how when the ultrasound was developed, it was a diagnostic tool, but as you describe it, it was also a narrative device. There's storytelling happening in these prenatal diagnostic exams.

Amanda Hess: I became really interested in prenatal diagnosis and its very quick spread after my pregnancy. You're right, I'm interested in it as a narrative device. I'm less interested in arguing whether it should exist and which technologies ought to exist. The way that it actually intersects with my life is how it makes people think about themselves and their kids. After that abnormal ultrasound, I had another doctor do an ultrasound to get a second opinion because I was like, "I don't like this first doctor who had said he saw something he doesn't like. I'm going to try somebody else and see what they see. All of these doctors are they're great."

She saw something that suggested to her that the baby's brain might be severely underdeveloped, which is not good news to get. After I got this alarming news that there might be a genetic condition, I got this very catastrophic news. It felt that way to me. I needed to wait a week to get an appointment with this guy who does fetal MRIs, which is a combination of terms that I had not previously heard put together.

I had a fetal MRI. He took a closer look at the brain and said that it was completely normal, which made me feel great, obviously. Later, as I was reflecting back on this, I was thinking about just this experience of the false positive or the false indication that something is wrong, and then the release that comes at the revelation that in fact the baby is normal, or in this case, that my baby's brain was normal. I felt like it's such an odd journey to go on with your child before they're even born. I was wondering about how that changed parents relationship with disability.

Just this increasingly common experience of being made to fear it and then being absolved of that possibility. It's something that comes up very frequently now with people who take NIPT tests early in pregnancy. What an NIPT does is it takes just based on a blood draw. It takes the pregnant person's blood and tests it for bits of fetal DNA, and it's able, through the analysis of those bits, to guess whether a child may have some kind of chromosomal condition. It's not very accurate, or it's not very precise.

If your blood is flagged as high risk of having a chromosomal condition, you're then usually counseled to get an amniocentesis that actually tests the baby's own cells directly. There are many people who've had this experience of getting a high-risk result for something like Turner syndrome, then having an amniocentesis that shows that their baby does not have Turner syndrome. I felt, even though all of my NIPTs were normal, I felt on the one hand a real kinship with these people who had had this experience, because my false positive experience was so traumatic.

I also felt apart from them in that my son was born with a genetic difference that can cause various disabilities. It was only after my own experience that I really understood that even as these tests are informing you whether your children might have a certain condition, what they're really selling is this reassurance to most parents that their children are "normal." It's a very fraught thing. I think it's even more fraught now than it was when I was writing the book, because the conditions for children with disabilities in the United States and for their families are worsening.

Molly Rosen: I want to move on to early parenthood. You go through something with your first son that, to me, just sounded incredibly difficult, which is that you had to strap on oxygen tubes every time he was sleeping. As someone who is very familiar with the difficulty of newborn sleep, that just sounds hard. You embarked on a journey where you tried out some of the baby products on the market to optimize sleep. I'm curious what your takeaways were from that.

Amanda Hess: Yes. Before my son was born, my husband and I learned about the SNOO, which is this robotic bassinet that sways back and forth and emits a whooshing sound that mimics the womb. The SNOO promises that SNOO babies, it says, on average, sleep one to two hours more than babies who do not go to sleep in the SNOO. If you've ever had a baby, one to two hours is like a lifetime. That's such a long period of time to suggest that you can add to your baby's sleep.

I was like, "I am using this thing, and I'm going to try to get my one to two hours out of it that I had been promised or whatever." I didn't buy it from the company. I bought it secondhand, so I didn't have any of its troubleshooting access. It meant that I was also then going online to SNOO online communities of parents, being like, "How do I get this thing to work? It says to actually make my child sleep more," because he was not a great or easy sleeper.

The thing that I really took away from that experience was this device, which not only promised to improve my baby's sleep, but also promised to improve my understanding of my baby's sleep in that it also spat out this data and insights into when he had woken up, when he was fussing, when he was going back to sleep. The cumulative hours he had slept had actually gotten in the way of me really understanding him and what he needed for sleep. After I used that, I became curious about all of these other products that are on the market.

Smart baby cameras, the Owlet, which is a quasi-medical sock that you put around your child's ankle that gives you insight into your child's pulse and oxygen saturation and stuff like that. I really came to understand, because I was using a real medical device, I wanted only to get rid of this device. I only wanted to banish it from my home. I was so excited when he was seven months and we could get rid of it. He had grown out of it.

The idea that this is now a precious commodity that tech companies are selling to people to bring the medical environment into their home, I think, is so interesting and speaks to just this tantalizing idea that we can completely control and optimize everything about our baby's health and their sleep. It makes sense to me that so many of these things are focused on sleep, because it's only when your newborn is knocked out that it seems like you have any control over them, really.

Molly Rosen: Yes. That's actually a big takeaway of mine from your book, was that it's about technology, but I also saw it as really about you as an individual working with all these different systems: the medical system, the economy, these technology platforms. I'm curious how your experience in writing this book left you thinking about the control that we like to pretend that we have over our lives.

Amanda Hess: Yes. I mean, I think because I experienced this profound loss in control during my pregnancy, it actually helped me, when my son was actually born, to let go of that a little bit. I saw a lot of peers and friends who I think were really in the thick of that in the newborn stage, just trying to make sure that nothing bad happened, that nothing south of normal was happening, or whatever. I was like, "I already know that something abnormal has happened, and that, for whatever reason, has given me the confidence that it's going to be okay." I also think the older your kids get, the less control you have over them, and the easier it is to see that you never really had that control.

They become their own person, and you realize that it was the same personality that they've had from the moment you first held them. It's only really in pregnancy and then this newborn stage when I think technology companies can provide this fantasy that you do have total control and that every decision that you make will have some profound effect over their future. I don't know if it was writing the book or just having my kids grow up and grow away from me a little bit, that let me understand that that was the thing that I had really been looking for, and that is so elusive and can't actually be delivered to a parent.

Molly Rosen: You said something really interesting about the period tracker app, which I think has come up a couple times, which is that you see this as technology companies getting us used to the need to have this kind of outside authority telling us this information about our very personal lives. I have noticed, actually becoming a parent, that I'm willing to compromise on some things with technology that I don't think I would have otherwise. I think because it feels so important. For example, my husband and I use this app tracking our baby's sleep that uses AI to have these predictive windows about when he should go to bed. We sometimes joke that I don't know if we would know when he's supposed to sleep. Embarrassingly, I think we wouldn't know without the app.

Amanda Hess: I mean, I really felt like during pregnancy I was trained to see myself as somebody who needed to be surveilled, that my pregnancy needed to be surveilled in order for me to do it correctly. I became comfortable with that. Then once my child was born, it was like, "Okay, you're the surveiller now. You're in this surveilling seat. You have the app on your phone that monitors your baby." I tried out this camera in my kid's room called the Nanit, which is an AI-enabled baby monitor. I used it because the baby monitor that I had used when my son was a baby, it was a video monitor, but it was not AI-enabled.

I wanted to see what these emerging technologies were like. I really delighted in the images that it showed me. It does this thing where, through machine learning, it monitors when your child is moving in some way, and it captures video and puts it in a little feed for you in the morning. I could see when my kids were rustling in their sleep or when they got up or when they said something. Just this little movie made of surveillance footage of my kids. Obviously, I think my kids are the most beautiful people in the world. I was like, "Oh, they're so cute." Then it wasn't until one night I laid down with my son to help him try to go to sleep right next to him, where he is in the bed, that I was able to see what he sees from this camera.

It was just four glowing red eyes that was watching them. It made me really question how our kids are experiencing these things and how surveillance is becoming equated to care, either through these smart technologies in the nursery, or just how often parents are putting their phones in their kids' faces, taking photos of them, or whatever. My kids have been in a daycare where their caretakers there take photos of them and send them to me so I can feel as if I'm taking care of them through photographing their activities or whatever. I think there's a training that's happening that I think only makes us and them more vulnerable to whatever products or even government projects are coming next.

Molly Rosen: I think some of these apps promise, like you say, that if we just had the right data, if we have enough information, we can solve all of our own problems. You alluded earlier to how there could be better disability services in a lot of the United States. The United States is a country without any federal paid parental leave. Many people don't have leave or have very short leave.

You write about how, after your sons were born, "The only reason that I could pay other women to care for him while I work was because my work was valued more than theirs. My salary was higher than the cost of the care, even as it was obvious to me that the true value of the caregiver's work exceeded my own. If I had to choose which was more important, publishing an article or feeding children, I would choose the children every time." These are words that, when I read them, felt like they had been lifted out of my own head.

Amanda Hess: I mean, I think what we get is a lot of information and insights and data and advice when what we actually need is support. I think a lot of these technologies just encourage us to pay more attention to our own kids when we need to be figuring out how we can have a vision of taking care of other people's kids and allowing other people to take care of our kids. Not in a way that is part of the care economy, but that is just built into our society. The thing that I want more than anything thing is a public kitchen.

This is something that has existed in some socialist communities and has been proposed by various socialist feminists for a long time. For me, you can give me as many tips about how I should cut up my baby's food that you want, but the thing that I really need is other people around when I'm feeding my baby, because I found that that was the most isolating thing. My baby and now my kids need to eat all of the time. I have a kitchen inside my apartment where only my family lives. That's where I prepare food for them.

That's where they eat. It's difficult to feed them, even in a restaurant, and of course, it's expensive. Some kind of solution that made feeding kids a communal responsibility, I think, would be so powerful. I think also to your point, I'm doing this interview with you while my younger son is in daycare. If you ask me, what do I think is more important to do with this hour: to have this conversation with you, which has been so lovely, or for my child to be fed, to be supervised?

Obviously, it's more important for my child to be fed and supervised. I think the capitalist system that we live in purposefully devalues that work because it doesn't directly create a profit. The only profit that it creates is indirectly through me being able to work. I think about that anytime I sit here talking to anyone about my kids, when they're not here at my feet, complaining about being hungry, and asking me to feed them.

Molly Rosen: Amanda, thank you very much.

Amanda Hess: Thank you so much. This is really fun.

Molly Rosen: Amanda Hess is the author of the new book Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age.

Brooke Gladstone: Thanks for tuning in to this midweek podcast. Be sure to check out the big show on Friday about how artificial intelligence seems to have seeped into every corner of our lives. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[MUSIC]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.