Working Class vs Protesters: 1970 and the Democratic Party Divide

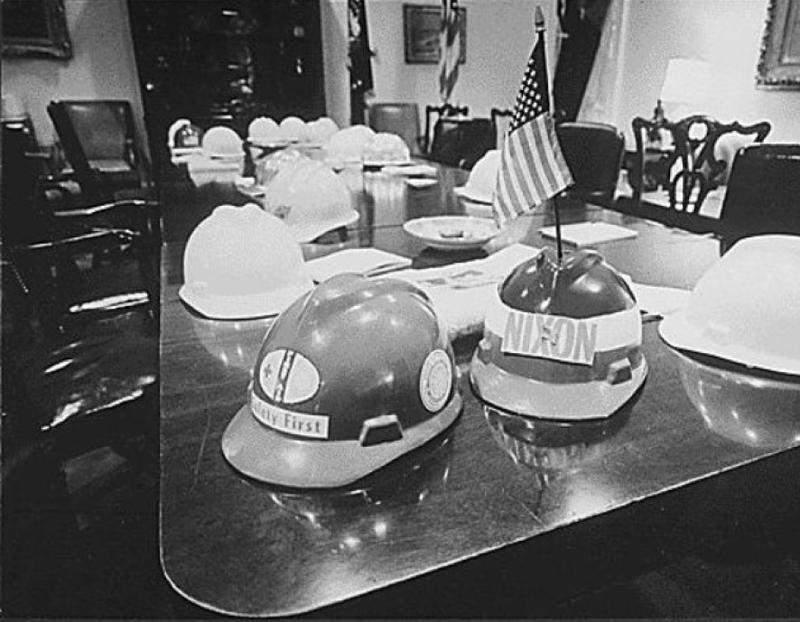

( General Services Administration. National Archives and Records Service. Office of Presidential Libraries. Office of Presidential Papers. / Wikimedia Commons )

[music]

Voice-over: Listener-supported WNYC Studios. [music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, a history segment that's largely about one day in the history of the culture wars, 50 years ago this spring. That my guest says was pivotal in moving the country toward where we are today. It's in a new book by political analyst David Paul Kuhn. Its main focus is the day of May 8, 1970, when a big anti-Vietnam war demonstration in lower Manhattan was met by a large group of construction workers, many of them involved in building the World Trade Center. The confrontation led, the name of the book is The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution. The New Yorker historian, Jill Lepore, calls the book, riveting. Democratic strategist James Carville calls it perhaps the best book ever written on how Democrats lost the white working class. It's a New York Times recommended book for this summer. David Paul Kuhn has served as the chief political writer for CBS News online, then a senior political writer for Politico, and chief political correspondent at RealClearPolitics. David, thanks for coming on with us again. Welcome back to WNYC.

David Paul Kuhn: Thanks so much, Brian. It's a pleasure.

Brian: Set the scene for us. May 8, 1970. What was going on in the Vietnam War and what was going on in the protest movement?

David: Absolutely. Why I think we have to widen the lens a little bit to April 20, 1970. Nixon pledges to withdraw 150,000 troops. The anti-war movement is flagging. Newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune declared that Nixon talked like a man who believes the war is over. 10 days later, Nixon announces the incursion into Cambodia. Its upheaval unlike anything seen in years across the nation. The anti-war movement reinvigorates. ROTC facilities are ransacked and firebomb from Maryland to Oregon State. Then that leads into Kent State. On Monday, May 4, there had been in that unknown place in Ohio relatively. There had been disorder across the weekend and effectively on Monday, the tragic 13 seconds where four students die, including, most tragically, perhaps most famously, I should say, was the young man from Plainview Long Island, a suburb of New York City, Jeffrey Miller, who was in that most infamous of photographs. At the same time, the anti-war movement then invigorates as it never had. Meanwhile, New York City, I should just say, to an extent that we can't even imagine today and that is from firebombs across the country which causes the Dow Jones to fall, have its worst loss since JFK was assassinated. Then basically throughout the week, throughout New York City the anti-war movement is in the streets, the movement itself, meaning just activists themselves on the left are in the streets. They're battling with police, et cetera. At the same time, downtown New York City is going through a second "skyscraper age" to quote The New York Times architecture critic at the time. The modern financial district that we see now. It was being built most famously as you know, the World Trade Center. By an absence of history into a space less than a kilometer wide because there's no Battery Park City, two groups that were unfathomable to each other at the time, construction workers and-- we'll just call them hardhats for shorthand and then we'll just allow for another shorthand, hippies, are condensed into this little space. As the anti-war movement has invigorated like never before, the construction workers who are disproportionally a majority of them are veterans. This 5,000 of them just at the World Trade Center alone. They're disproportionately veterans of Korea World War II, some were Vietnam. They're much more likely than the protesters to have kin and kind in the war. Obviously, there's been brooding strain between-- Actually I should say not obviously. There's been brooding strain between these two classes of traditional democratic constituencies for years. It explodes that Friday, May 8, the 25th anniversary, I should note of VE Day. It's a moment where really the old left attack the new.

Brian: How much of a claim do you make about this being a turning point in the politics of Democrats, Republicans, and the white working-class?

David: I don't use the word turning point. First of all, I think that's absurdly overused. I don't think there are many turning points in history. Most historical moments we call turning points have antecedents. Cultural populism, for example, in the Republican Party, which we're seeing displayed at the current convention goes back to the Whigs in 1840. I would say I read about it as a microcosm. In this moment when Democrats lose the old left and the FDR coalition fractures, this is the most potent, cinematic and violent and brutal moment that captures this fissure between the old iconic FDR Democrat, and let's just call it the McGovern coalition, which eventually becomes the Democratic coalition, but first in those years, was actually the John Lindsay coalition.

Brian: Mayor John Lindsay, liberal Republican in fact at the time. You portray both sides as truly believing they were the truer patriots. Did they have different notions of what that meant? On the surface, this was about the Vietnam War, but so often culture war conflicts about lots of things. When you scratch below the surface, turn out to be about race. The subtitle of your book is about how the Democrats lost the white working class. To what degree would you say race is a subtext in this, which might've been mostly between white construction workers and white, what you call hippies?

David: First of all, let's just say that it's impossible-- We're getting to the most loaded question of all in the modern American politics in terms of how the Democrats lost their original coalition, which is were they all entirely bigots or was it all racial? One does not preclude the other, in other words , racism is a factor in the fissure of the Democratic coalition in the '60s and '70s. It's not precluded by all these other issues. I would say the story of race and what people call the southern flip, the politics of the deep South is a well-told story. What is not told is the class strain between whites. Whites is just a way of saying class politics in American life because racism enters less in the tensions between whites. What you have at this time is the beginning of the college-educated, the very beginning of the college-educated coastal Democratic Party. At the same time, when there was still working-- A majority of New York City at this time were working-class whites. You have this strain between them and really what Lindsay came to embody. This new liberalism, 1969, the word Lindsay and liberal is used for the first time against John Lindsay. It's impossible to just aggregate all these issues, but this day it's no accident that white construction workers, largely white are attacking largely white, almost entirely white college-educated and college students and some high school students, I should note. Because what we forget so much about this time was when you-- As I back up the narrative with Pauline, I had put the point in the notes because I don't want to bore the reader. It is utterly forgotten by history how much resentment and tension and anger there was among blue-collar whites towards what were really thought of as their liberal betters by this moment. This strain that I think the commentary it woke up to in 19-- Excuse me, in 2016 has its roots in these years. In some ways, it's stunning how much history does indeed rhyme because in 1969, after Nixon shocks the best media, the commentariat and makes his comeback. It's easy to forget that his political career was declared dead by ABC News in 1962, et cetera. When Nixon mounted shocking come back, and this is months after Chicago '68, and how the media misread what happened in Chicago '68. In 1969, just like in 2016, the media suddenly "rediscovered" the white working class. That word, rediscovered, comes from a Washington Post front-page story in 1969 because it was news that the news was even paying attention to these welders. It's remarkable how much many of the tensions that still dog our politics if you will find their roots in these years.

Brian: Nixon uses that clearly in his reelection "silent majority". In 1972, we know Republican presidents and presidential candidates have used it ever since. Is Donald Trump really such a departure as some people see him as?

David: That's a really big question, Brian. Donald Trump in many ways is generous. Is the cultural populism that he in some ways that he clearly taps into and often clumsily and without any sense of American history. Is that new to American politics or to the Republican strategic game plan? Absolutely not. Nixon wrote the Republican playbook, the modern Republican playbook I should add, because as I noted earlier there were antecedents to it. That playbook is pushed forward by Ronald Reagan and eventually and t he great ferment in American politics in the late '60s and early '70s really solidifies in 1980 with Reagan Democrats. Donald Trump is both a departure in many respects, but he certainly and his surrogates certainly attempt to put forward the cultural populism that has undermined Democrats and helped Republicans for the last half-century.

Brian: Joe Biden comes out of the white working-class. The Democrats are hoping that he's positioned to be more appealing to them or look more acceptable than Hillary Clinton did in 2016 obviously. How do you think that's going?

David: I looked at all the polling. I looked at wherever information is possible. I would say it's clearly Trump's performing about 10 points weak with the white working-class, and I want to stress that word "about" than he did in the 2016 election. Biden appears a few points stronger. I would say there's a lot of unrealized potential for Joe Biden still with the white working-class. There were some missed opportunities last week on that front during the Democratic Convention. I think that's the standing of the race. It's very hard to look at. If you aggregate cross tabs of polling, you're still dealing with a large margin of error. Clearly, Trump has serious headwinds. He is the unlikely victor in the coming election, but Biden has more unrealized opportunity because of the background that you know than it's clearly realized yet.

Brian: What were you referring to a minute ago as the missed opportunities in this respect at the Democratic Convention?

David: One example was I would say they underemphasized the economy last week. I would say that it's a Trump strength despite the current circumstances of the United States. One aspect of the convention that could have been stressed more was the economy. They also could have played into concerns about China that are shared on the left on the right.

Brian: Looking back to 1970, in that context and the subject of your book, we didn't yet have the globalization of manufacturing and flight of pretty well-paying white working-class jobs that we have today that people often attribute their turning to Donald Trump because of.

David: We did in New York City, Brian.

Brian: Go ahead.

David: That's why New York City is such a fascinating microcosm because New York City in the '50s as a manufacturing center of the country. They're going to lose 70,000 longshoremen in this period leading into the Lindsay era. It's going to lose more manufacturing jobs. The deindustrialization of America hits New York City before it hits America, but it was in that way. That's why New York City is such a fascinating microcosm in this period. I would say incongruently because we think of modern New York, which is very different than that New York. There's a dress manufacturer I talk about at the very end of one chapter who says, "This is a blue-collar city, but all of our opportunities are white-collar." The city was changing dramatically in this period, including the rise of Yuppiedom. New York City was experienced at the industrialization, that's why it's so fascinating.

Brian: Lastly, Democrats, let's say working-class populists like Bernie Sanders. Populists trying to appeal to the working class across racial lines. Those people fail time after time because you could get in theory, white and people of color resentment against the professional class as well as the banking class which the liberal professional class is already against. That attempt to unify on the basis of class always seems to break down on the basis of race. Do you see it going any differently potentially in our last 30 seconds?

David: I would just say that the test, the trial balloons for that strategy have been very flawed. I talk about the Bobby Kennedy-Gene McCarthy dynamic in 1968 in my book. Gene McCarthy was rallying college students. There's one moment where he's talking to college students and he talks about how Bobby Kennedy is appealing to the "less-intelligent and less-educated people in America". Arthur Schlesinger reports that McCarthy was declaring a revolution against the proletariat. In other words, the Bobby Kennedy idea was never finished for obvious reasons. I would say that pan-racial class-based appeal has yet to be successfully put forward by the Democratic candidate.

Brian: David Paul Kuhn's new book is called The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution. Thank you so much for coming on.

David: Thanks, Brian. [music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.