Why Did Trump Keep Other Countries' Nuclear Secrets At Mar-a-Lago?

( Jon Elswick / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning everyone. Usually, we begin this program with something about an important news story of the day. Today though, let me begin with something about a news story from April. A new story that's five months old that we've never mentioned before on this show. It's about a guilty plea in a criminal fraud case by a man named Brian Kolfage, I think I said his name right.

Brian Kolfage as The Washington Post told the story on April 21st, Brian Kolfage, a disabled veteran, who headed a 25 million fundraising effort for a US-Mexico border wall with the help of former Trump aid, Steve Bannon has pleaded guilty in connection to defrauding donors for his own game. It says Kolfage, an amputee, who lost three limbs serving in Iraq could serve more than five years in prison.

He was accused of using more than $350,000 in donations on personal expenses, such as home renovations and vehicle payments after telling We Build The Wall campaign contributors that he would not take a cut of the collections or give himself a salary. On Thursday, that Thursday in April, in federal court, in Manhattan, the Post reported, he admitted to siphoning off money for himself and also pleaded guilty to tax crimes for failing to report that income. That from The Washington Post, April 21st. I'm guessing that most of you have never heard of Brian Kolfage or his conviction until this moment.

You may also not have heard about Steve Bannon's indictment in that case. He was arrested and charged back in 2020 for taking more than a million dollars for himself from that money raised from donors, supposedly to build that wall. Fittingly, perhaps, Bannon was arrested on a 150-foot yacht floating in the Long Island Sound, and not only a yacht, a super yacht, as it's known at that length, 150 feet. A super yacht owned by a billionaire businessman friend of Bannon's, a yacht valued at $28 million, according to multiple press reports at the time.

Bannon never faced trial in that case because President Trump, before he left office, pardoned Bannon. Trump did not pardon disabled Iraq war veteran, Brian Kolfage for defrauding Trump supporters and pocketing that $350,000, or two other not famous guys who were also charged. He only pardoned Bannon, his former chief strategist, January 6th, provocateur and far-right icon for the charges of stealing those million bucks from people who gave it for building a wall at the border.

They thought, not for building an extension on Steve Bannon's house or whatever he might have used it for. This morning, as you may have been hearing, Bannon was arrested by the state of New York and charged for basically the same crime by the Manhattan DA, Alvin Bragg. Trump's pardon only got Bannon off the hook for federal crimes. That's how presidential pardons work. What Bannon allegedly did is also a crime in the jurisdiction of New York, and he has now been formally charged.

Still not known is whether Trump will be charged with any of the things he's being investigated for. Interfering with the certification of the presidential election in

Georgia, sedition or whatever charge in connection with January 6th, fraudulent valuation of various properties in New York, or his resistance to returning classified documents to the government after taking them home to Mar-a-Lago after his presidency. That one in the news very much these days, of course.

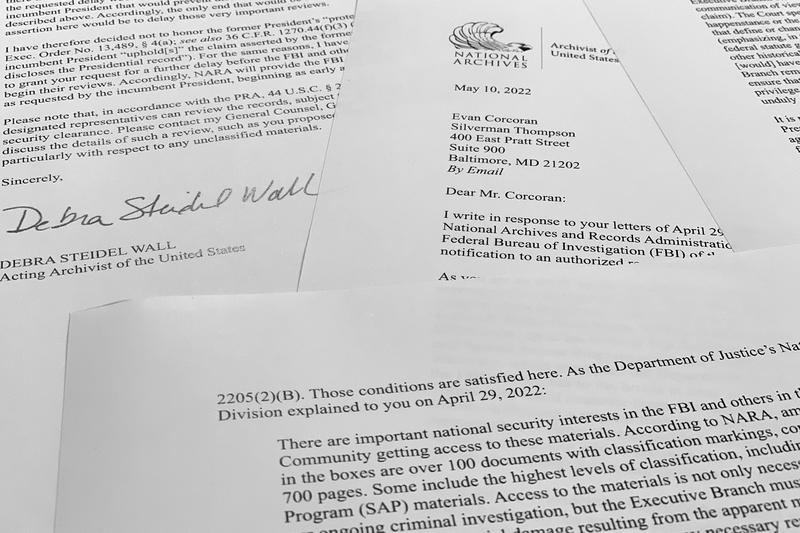

In that last case, The Washington Post reported Tuesday night that those documents contained materials pertaining to a foreign country's nuclear capabilities. Joining us now to talk about Bannon turning himself into Alvin Bragg, that foreign nuclear government's military secrets hanging around at Mar-a-Lago and more is one of the reporters on that Tuesday article, Washington Post correspondent, Devlin Barrett who covers the FBI and the justice department, and is author of October Surprise: How the FBI Tried to Save Itself and Crashed an Election, which was about the Hillary Clinton classified documents investigation. Devlin, thanks for coming on as your story is in the spotlight. Welcome back to WNYC.

Devlin Barrett: Hi, Brian. Thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Can we start with that little piece of history of Donald Trump pardoning Steve Bannon for allegedly pocketing a million dollars of Trump supporters' donations that they thought was going to building that wall, but not pardoning the disabled Iraq war vet accused in the scheme with Bannon. Did Trump ever say publicly to your knowledge, why he pardoned Bannon or didn't pardon Bannon's partners in that case?

Devlin Barrett: I think what Trump has said publicly on the pardons is that and you got to remember Bannon's pardon came as part of a batch of pardons for folks like Roger Stone. I think Trump takes the view often that people close to him who are charged with crimes, one, should not be charged with crimes, and two, his argument is that these cases are all some variant of politically motivated witchhunt by his enemies in the deep state.

That's his rationale and argument for doing these things. I would say that it seems although he is often maddeningly nonspecific in how he talks about some of these issues. I would say, as best I can tell he pardons Bannon and not the others because the former President Trump considered Bannon one of his guys, and that did not apply to people beyond Bannon in that case.

Brian Lehrer: Despite there being so loyal to the idea of building that wall and all of that stuff. The brand new news here this is less than an hour old in the nine o'clock hour, Steve Bannon surrenders to Manhattan DA. I'm reading from Politico, "Longtime Trump ally and former White House advisor, Steve Bannon handed himself over to New York state prosecutors. Bannon, 68, reported to the Manhattan District Attorney's office a little after 9:00 AM.

The office confirmed his pending indictment. He faces criminal charges for his role in a group that raised $25 million to build the wall along the border with Mexico, but allegedly pocketed some $1 million in donations." That from Politico just moments ago. The new charges in that case, at the state level, in New York, they are for exactly the same thing, is that your understanding?

Devlin Barrett: Yes, it's the allegedly fraudulent conduct around the wall building fundraising. Remember, the allegation is that they basically did not spend a lot of this money on any wall-building efforts, they spent it on themselves. That's the original allegation in the federal case. We have every reason to believe, our understanding I should say is that that will be the central allegation when the state charges are unsealed against Bannon.

Brian Lehrer: That's not double jeopardy that is being charged for the same crime after you've been acquitted or in this case, pardoned for that crime.

Devlin Barrett: Brian, that's a super interesting question. If you use it to compare it to a similar, but not identical case. Paul Manafort, former campaign chairman, I should say. His former campaign chairman was put to trial and convicted of fraud, and then Trump pardoned him. Then the Manhattan DA charged Manafort with essentially the same facts as state crimes. The court eventually ruled that you can't do that, that's double jeopardy.

Here you have a slightly different scenario where Bannon was charged, never put to trial, and because he was pardoned before he could go to trial. I expect Bannon's lawyers will make some challenge to this indictment in saying it's still double jeopardy even if he didn't go to trial on those charges.

Brian Lehrer: Because presidential pardons apply to federal charges, but not to state charges.

Devlin Barrett: Right. I think that's an interesting legal question that I don't believe is entirely resolved. I don't think we can predict the future of that right now. Clearly, though, the Manhattan DA's office believes there is enough of a difference between the facts of the Manafort case and the facts of the Bannon case that they think they can go to trial and get a conviction.

Brian Lehrer: Bannon of course calls these charges political. Not saying yet if he's out on bail, do you happen to know if New York's famous recent bail reform law applies to allegedly defrauding Trump supporters out of a million dollars?

Devlin Barrett: I would say he's likely to get bail, although you never know what prosecutors are going to ask for or what a judge will do ahead of time. I would say he's likely to get bail, not so much because of the state's bail laws, but because white- collar defendants, in particular, particularly ones who have been in the system before and showing up for court are essentially trusted on certain bond conditions to keep doing so.

One thing to remember about Bannon and I know that the news comes fast and heavy these days, but one thing to remember about Bannon is he was just convicted in federal court two months ago, in Washington, DC for contempt of Congress. He is an already convicted person. His legal saga is one of the most amazing criminal courts episodes of the entire Trump era.

Brian Lehrer: Would Brian Kolfage, the disabled Iraq War vet who pleaded guilty in

the scheme be likely to testify against Bannon? This may be outside of your reporting assignment, but do you know if cooperation with the Government was part of whatever plea arrangement he made?

Devlin Barrett: I don't believe that was part of it, but I can find out. Look, even if you have a deal with the feds, that doesn't necessarily translate into a testimony for the state prosecutors. The other thing to keep in mind, though, is that a lot of people decide to cooperate after they've already gone to prison. One of the things that can happen is people can plead guilty or be convicted, go in and decide that in order to try to shorten their sentence, to try to get some break on their prison term, that they're willing to cooperate.

Those are the things to look for. I think it's the right question to be asking because certainly, there is still a potential incentive for those people to cooperate, even in a state case. It gets very complicated when you talk about cooperation in the state case when you're sentenced in a federal law and there's some extra wrinkles to that process because of the two different venues.

Brian Lehrer: You cover the FBI and the Justice Department for The Washington Post, you're not a political analyst, but do you have any sense of whether Trump world, MAGA world is likely to rise up in support of Steve Bannon in this case and back him up on this being a political accusation, even though the charge is basically stealing money from them, stealing money from Trump and people connected to Trump in some way, or constantly raising money off of Trump's politics, off of Trump's troubles, that even applies to January 6th in the classified documents investigation and other things that actually help them fundraise?

Since this is alleged abuse of money that those people gave to the organization Steve Bannon was connected with, are they lining up behind him around the country? Do you have any sense of it?

Devlin Barrett: I will say this again, having covered his past trial, I would say that it appears to me and not only am I not a political analyst, I'm probably a bad one when I try to be, but it is striking to me the degree to which-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Everybody [crosstalk] because most people are but anyway, go ahead.

Devlin Barrett: It is striking to me the degree to which even when you see these allegations of fraud and manipulation and misuse of what I tend to think of as his fan base or Trump's fan base, the fans themselves don't do it that way, most of them. The fans themselves view these cases as often as the president describes them, as political payback, not based on meaningful facts or facts they care about, I guess is how I think of it in some ways. I don't think you have seen yet a turning off of the fans away from folks like Bannon.

In fact, one of the really remarkable elements of the Bannon trial this summer, and I expect will be a remarkable element of any Bannon trial that happens in New York is at that trial in July, Steve Bannon came out and talked publicly after court every day

and just railed against the machine and the process and had a very popular podcast that did great numbers while he was on trial for these things. I really think in a weird way, the attention and the charges can increase popularity.

Devlin Barrett: Devlin Barrett, who covers the Justice Department in the FBI for The Washington Post is our guest. Let's go on to your story called Materials on Foreign Nations Nuclear Capabilities Seized at Trump's Mar-a-Lago. This is the big story, in that case, the last day and a half or so, and you open that article with the context of how closely guarded some of the seized documents usually are. Would you begin with that context for our listeners?

Brian Lehrer: Sure. I think one of the things I really want to explain because the world of classified information is a strange world. While there's a lot of movies about it, there's a lot of talk about it, it's actually not a very well-understood world, and that's by design, obviously. If you build a world of secrets, you don't want to talk about how the world of secrets works. The point of this context and description was to try to highlight to the reader.

Some of this stuff is classified under what's called Special Access Programs. It's a very bland term, but it means something very important in the government. What it means is that only very high-level people are allowed to let other people know about this information. It's sort of if you think of top secret as like a big pool of information, and only some people are allowed in that pool, Special Access Programs are a very small circle in that pool, and a very small number of human beings are allowed into that small circle.

For example, some of the information we're told that was taken from Mar-a-Lago was so closely held that only some cabinet-level secretaries, not all of them by any stretch, the President, and a few near cabinet-level officials had the authority to tell anyone else about what those programs did. You're talking about information that was in some cases restricted to just a few dozen people in the entire government. That's one way of understanding the concerns and alarms that this case has generated among the intelligence agency.

Brian Lehrer: In that context, to go off on a little bit of a tangent, is that context also relevant to who the special master might be, who the federal judge in the case selects to do an independent review of these documents? I'll remind the listeners that Trump and the Justice Department are supposed to suggest people for that role to the judge by tomorrow. I imagine they won't suggest the same people, but might there be only a couple of dozen people to use your number in the whole country who have the security clearance to even be considered for special master?

Devlin Barrett: It's a great point, and it's one of the things I have been struggling to understand, as this special master issue has come up. The special master was a tool in a device in a position designed to deal with one problem, attorney-client privilege, but in this case, in the Mar-a-Lago case, what the judge is proposing is to have a special master deal with actually not just attorney-client privilege issues, but too much more complicated issues one being, as you said, highly, highly classified

information. The other being executive privilege, and how to define it for a former president, if it applies at all.

These are incredibly complicated questions and issues, and they're not well defined in the courts under the current cases we can look at. To your question, I would say not only is it greatly complicated by the notion that, in theory, only a very small number of humans could do this, you would also have to find a human who has that understanding or familiarity with classified, who also has a good grasp of executive privilege, and attorney-client privilege.

At some point, you're talking about maybe half a dozen lawyers in the whole country who could say like, from day one, I can do this. I will say one caveat to that, though, and that this is important is you could have, for example, a former judge who has some understanding of the classified world, and who could be authorized if the government chose to authorize them to be read into these highly, highly sensitive programs. That, in theory, could happen. I think, to your main point, my main answer would be what the judge is proposing is incredibly complicated and difficult to pull off, and I'm not sure exactly how this is going to work.

Brian Lehrer: The name Stephen Breyer comes to mind, but I don't know if that could be acceptable to Trump.

Devlin Barrett: Right. I have seen that name suggested.

Brian Lehrer: Last I saw, by the way, it was still unknown if the Justice Department is going to appeal the ruling allowing Trump's request for a special master, and that's a matter of debate in legal circles as to whether it's worth the fight. Do you have an analysis of the pros and cons as the Justice Department sees it?

Devlin Barrett: Right. I think first off, an appeal would probably slow down the investigation because you'd be kicking up an issue that in theory could go all the way to the Supreme Court and there's no way that doesn't eat up some clock. That's not to say that this investigation was going to be resolved in two weeks or a month anyway. I think that is also not very realistic, but I do think if you are going to appeal this issue up high, you are sort of baking in more time before you can really get this investigation fully up and running again.

However, the other thing to think about here, and it's a big riddle for the Justice Department to try to solve is the judge has laid out a fairly aggressive view of executive privilege applying to a former president. The Justice Department has already indicated they do not believe that applies to a former president. I think the challenge for the Justice Department is do you just let that view sit in the court system as if it is okay and not challenge it and worry that somewhere down the road, that analysis will bite you even harder in the future. Now that thought process, that concern would argue for appealing, right?

The flip side of that problem is what if you appeal and a court that is generally conservative, 6-3 conservative court, three of the justices appointed by Trump sides with Trump and says executive privilege does have an application to former

presidents. Then you would not only have lost in this case. You would have in theory lost in a bunch of future cases, and that might be something you want to avoid. I think all those things go into the calculus,

Brian Lehrer: A few very difficult decisions facing Merrick Garland, not just this one, but a few that most of our listeners could tick off at this point. Certainly not the least of which is whether to indict Trump on anything having to do with this or having anything to do with January 6th, or the big lie. We're going to take a one-minute break, then we're going to continue with Devlin Barrett who covers the FBI and the Justice Department for The Washington Post. We'll then get into his headline that the document sees that Mar-a-Lago include materials on a foreign country's nuclear capabilities.

We'll have time for just a couple of phone calls for him, but listeners, on any of these things, the Steve Bannon surrender to Manhattan DA, Alvin Bragg this morning, or any of these other aspects that we're talking about 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 or to be really quick and efficient tweet your question @brianlehrer and stay with us. Brian Lehrer on WNYC with Washington Post FBI and justice correspondent, Devlin Barrett, who is co-author of the article that dropped Tuesday night called Document seized at Mar-a-Lago include Materials on a Foreign Country's Nuclear Capabilities. Can you get any more specific about what country or about its capabilities?

Devlin Barrett: I can tell you what country because I don't know. I am trying to figure that out. I can tell you that what was described to us was a document that describes a foreign government's military defences, both their conventional and nuclear capability, military capability. That is obviously a concern and to be clear, this followed previous reporting we'd done that one of the thing, one of the types of classified information they were looking for in the course of this investigation was any classified documents about nuclear weapons.

What we now know because it's public is the subpoena issued in May to Trump was for a long list of different types of classified documents. The classification was very strange and there's a lot of different categories, but in that subpoena, it listed all the major categories and one of those categories was the category used for nuclear weapons and so this follows on that prior reporting.

Brian Lehrer: You're sourcing for this revelation is people familiar with the matter, it's that general, and I certainly won't ask you to disclose your sources, which you would never do even if I did ask, but can I assume from that language that it was more than one person?

Devlin Barrett: You can absolutely assume it's more than one person.

Brian Lehrer: What would the potential implications be of another country's nuclear secrets being stored relatively casually at a resort or a residence like that and where Trump himself doesn't even stay all the time?

Devlin Barrett: I think a couple of things. One, a lot of government nuclear capabilities are sort of known but not discussed, and some of them are of great

concern and some of them aren't. I think to your earlier question, it greatly matters what country we're talking about, but I also think our government and other governments treat information about nuclear capabilities particularly carefully, because there is always a concern that no matter how understood or generally accepted among foreign leaders is this information, you really don't want it out in the public world at all.

That's been the case since really the dawn of nuclear weapons, right? Even as there is more familiarity with how the technology works and who might have what, those things are all still very closely guarded secrets, not just by our government, but by other governments. No, all I was going to say is it's sensitive, not just to us, but it is likely sensitive information to the other country and so it's a potential intelligence issue. It's a potential diplomacy issue, and it's a potential national security issue.

Brian Lehrer: Intelligence issue, and of importance to other countries. I guess with this implication, even if they don't think nuclear saboteurs are rooting around closets at Mar-a-Lago, it could result in other countries officially or individual spies and other intelligence sources from other countries being hesitant about cooperating with the United States at that level of sensitive information.

Devlin Barrett: Right? I think that's one of the generalized concerns that intelligence officials have about the Mar-a-Lago case, that when it comes to highly guarded secrets within the government, one of the ways in which these countries all judge each other and decide what to share with each other is whether or not they think stuff is going to leak out or spill out.

The Mar-a-Lago case at least raises the possibility that some very sensitive things can spill out and that is always a concern, and that comes up in other elite cases. Obviously, the Mar-a-Lago case is unique among classified eite investigations, but it is a common issue in such cases.

Brian Lehrer: Christina, in central Harlem, you're on WNYC with Devlin Barrett from The Washington Post. Hi, Christina.

Christina: Morning, Brian, thanks for letting me pause this question to your guest. Comparing the two situations with Bannon, and I assume it was an Attorney General's bar who did not obstruct Bannon's charges being the DOJ charging him. My concern is if we wait like this, and if DOJ had waited to charge him until after the 2020 election and Trump couldn't have pardoned him, then we wouldn't be having this discussion so that brings up a strategy question for the DOJ, as it regards to all the Trump concerns that are in the pipeline, like when he's going to be charged.

We know he delays, and if he delays until either himself or DeSantis or somebody gets elected, if we have a Republican president in the next cycle, that person is going to appoint an Attorney General who won't allow pursuit of charges against Trump. I think the DOJ needs to really get their act together and start considering the timing of this and they definitely should appeal the special master, like you guys are saying it's impossible to find somebody so good but also, it's just a delay tactic.

It should be happening sooner than later with all the notorious ways that Trump continues to delay justice and it brings up one other thing that maybe our country should consider electing an Attorney General rather than having him appointed.

Brian Lehrer: Electing an Attorney General. Well, that's an interesting conversation. We have a series coming up on democracy in the United States, many aspects, that'll be next month, maybe that's one we should tackle. Should the US Attorney General be elected and then would it be through the electoral college or would it be a popular national election? David and Elizabeth, you're WNYC. Hi, David.

Devlin Barrett: Good morning, Brian. Listen, I just wanted to pause at something. It's not cynical or critical, but I was in the military, not in that area, but everybody who's in the military has to get a clearance, has to. We're told summarily and directly that the whole thing has to do with need-to-know. If you have a document, you have no need-to-know it, you shouldn't have it. There's also a custody chain agreement.

Also, President Biden did not give President Trump the daily as a courtesy. He's the only president, as far as I know, that doesn't get the daily briefing because President Biden said that he had reason. By the way, all that stuff that was on the floor is now what they call sour. It's forgotten, it's gone, so it has no value believe it or not. Again, I wasn't in that area, but anyone in the military, we were all yelled at, and rightly so. Need-to-know. If you don't have a need-to-know, you shouldn't have it and Trump messed up.

By the way, I just want to say something. We had to go through the FBI. The FBI work hard. Those guys are honest and know what they're doing and all this criticism is just stuff and it's a great show. I just wanted to offer you [unintelligible 00:31:02].

Brian Lehrer: David, thank you very much. Thank you for your perspective.

Devlin Barrett: Brian, can I make one point about that because I think the caller makes a really good point. A lot of people who work in the intelligence community say, "If this had been me, I would have been arrested already." There's an element of truth to that. However, one of the things I think people generally don't understand about the Mar-a-Lago case, in particular, is if President of the United States, as crazy as this may sound, never has a security clearance.

They're not read in and read out of classified programs the way every other person in the intelligence community is because of the unique position of being the president. Trump in this instance didn't sign the kinds of paperwork that everyone who has clearance signs, didn't make the kinds of attestations promising to not misuse material that everyone else signed. That doesn't mean he's off the hook, but it does mean this case is fundamentally different than almost every other mishandling classified information case I've ever covered.

Brian Lehrer: I know you have two minutes left before you have to go, but that leads me to two burning questions. One is I ask so many guests what the leading theories are about why Trump would take top secret classified documents to his private residence if he doesn't have a need-to-know. Nobody ever seems to have an answer

to the question of why. The other thing is your book, October Surprise, about the FBI's handling of the Hillary Clinton classified documents on her private server investigation during the 2016 presidential campaign suggests at least the question about how you would compare FBI director James Comey going public with criticism of Clinton despite not finding a crime there, so roundly criticized, to the Justice Department leaking things about this classified documents investigation if those are the sources.

Devlin Barrett: A couple of things. One, I think the Clinton email case is a very important comparison because there are a lot of similarities and there are some important differences in that Trump is not a current candidate for office. I know everyone assumes, expects him to run two years from now, but that's still a long ways away. What the FBI did in 2016, what Jim Comey did in 2016, the most impactful thing he did was 11 days before election day.

Also, the vast majority of the issues in Clinton's email server were not marked classified. They were discussions of topics that were classified in emails, but they weren't marked classified. It wasn't about classified documents the way this is about classified documents. To your question as to why would he do this, I think what's been described to us is a fairly disorganized, to call it a storage or paperwork practice is maybe too generous a term for it, but a fairly disorganized way of handling paper is the nicest, clearest way I can say it.

A lot of the stuff they found was just stuffed in boxes with a bunch of random other things. There doesn't seem to be any rhyme or reason to it. I think that's the best answer we have, but I understand that's not really a true answer yet.

Brian Lehrer: Washington Post correspondent, Devlin Barrett who covers the FBI and the Justice Department and is the author of October Surprise: How the FBI Tried to Save Itself and Crashed an Election. Thank you so much. So much information and very cogently presented. We really, really appreciate it.

Devlin Barrett: Thanks, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.