When Clarence Thomas Misunderstands Your Work

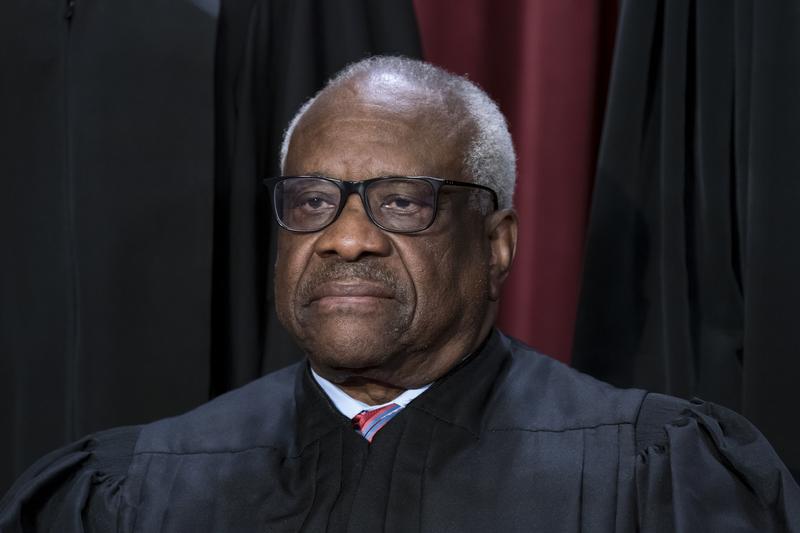

( J. Scott Applewhite, File / AP Photo )

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, something unusual. We are joined by WNYC's Alison Stewart, who of course hosts the show after this one, All of It with Alison Stewart from noon to two every weekday, the best arts and culture show anywhere, in addition to the other things it does well. Alison is coming on as a guest on this more news-oriented show because much to her surprise, she has found herself in the news. How? Because Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas cited Allison last month in his concurring opinion in the landmark case that declared affirmative action in higher education unconstitutional.

Allison is not pleased. In fact, she wrote an article on HuffPost called Clarence Thomas Cited My Work In His Affirmative Action Opinion. Here's What He Got Wrong. Now, what Justice Thomas cited was a book that Allison released in 2013 called First Class, The Legacy of Dunbar, America's First Black Public High School. Allison joins us now to further set the record straight.

Hi, Allison. Thanks for taking some time from prepping for your show to come on and have a conversation here.

Alison Stewart: Thanks for having me, Brian,

Brian Lehrer: Do you remember, by the way, that in 2013, which was five years before you came to work here, you were on with me as a guest for a book interview when First Class first came out?

Alison Stewart: I did remember that, yes. I think I'm sitting in the same studio that we sat in.

Brian Lehrer: Absolutely, you are. We're going to play a clip from that interview to help you make your point in a couple of minutes, but that was 10 years ago. Now you're back to talk about the book again. We can do this once a decade, Alison, not more. We don't usually have authors on twice for the same book, but it's not every day an author is in the news for saying they were misinterpreted by the Supreme Court. I'll read in a minute the specific passage where Thomas cites you in your book, but would you give our listeners some basic first, what was Dunbar? Why did you write a book about it in the first place?

Alison Stewart: Dunbar is this amazing story about the first Black public high school in the United States. It is a school that produced many of the glass ceiling breakers in our culture. The first Black senator after Reconstruction, Senator Ed Brook, the first Black federal judge, the first Black general in the army. The first Charles Drew who invented the Modern Blood bank, Billy Taylor, the jazz musician, Elizabeth Catlett, the great artist. It had this really interesting ecosystem because many of the first African-Americans to graduate from college couldn't get jobs in their fields. It was a group of hype that all became teachers.

The people in Dunbar were educated by hyper-educated people. The first Black graduate of Harvard was one of the principals. Many of the history teachers were trained as lawyers. Many of them were civil rights leaders. The principal of the school, one of the longest-standing principles, and one of the most important, I should say, was Anna Julia Cooper, the very famous feminist and civil rights icon. In the inter flap, I remember us writing, could we say this is a high school that changed America? We realized we really could because the architect of desegregation, Charles Hamilton Houston, was a graduate, and he trained the lawyers who argued Brown versus Board of Education to integrate schools.

It's this incredible story. What happened is, like a lot of these institutions, Dunbar had fell in incredibly hard times. The school fell into disrepair, the academic program faltered, and I realized the people who could tell the story of Dunbar were all in their 70s, 80s, and 90s, and their story was going to get lost. It became a little bit of myth about it when it really was a real place. Bearing the lead, my parents went there in the 40s, which is how I knew about it.

Brian Lehrer: Huh. Now I'll read for the listeners what Justice Thomas wrote, and then we'll discuss. Folks, in his written opinion, he's making the case that an education system without affirmative action, a system he calls meritocratic, can provide for Black equality better than the education system with affirmative action has done. He writes, for example, "Xavier University, an HBCU, Historically Black College University with only a small percentage of white students, has had better success at helping its low-income students move into the middle class than Harvard. Each of the top 10 HBCUs have a success rate above the national average. Why then would the court need to allow other universities to racially discriminate?" Discriminate is how he characterizes his affirmative action.

Right in the middle of that little passage, he drops a footnote, footnote 12, for those keeping score at home. It's footnote 12 that name-checks Alison and her book. It says, in the years preceding Brown versus Board of Education, of course, in the years preceding Brown, the most prominent example of an exemplary Black school was Dunbar High School, America's first public high school for Black students. Known for academics, the school attracted Black students from across the Washington DC area.

Then it goes on, Dunbar produced the first Black general in the US Army, the first Black federal court judge, and the first Black presidential cabinet member. Then the citation, A Stewart First Class, the Legacy of Dunbar 2013.

Alison Stewart: The way I found out about it, I've got the text up here, it says Monday, July 3rd, 6:01. This is from my friend, Jeff, who is the son of a Dunbar graduate. I got to know him. President of the Harvard Club, by the way in DC, says, "Hey, I just read the affirmative action decision and saw Clarence Thomas cited your book in his footnote concurrence, surprise face, to totally misinterpret your work. I'm sure I'm not the first person to share this, but just want the record to show that I'm appalled."

I was standing in Union Station in Washington DC when I got this text, and I was like, "What is Jeff--" Jeff's an attorney for the FCC, so I'm like, he's the guy who reads the footnotes. It was just such a shocking moment, not on my bingo card for 2023 that something like this would happen. I think I shared with you earlier that it struck me particularly hard because I had just taken my son to the Smithsonian National African-American Museum in DC.

Brian Lehrer: You're walking out of the National African-American Museum of the Smithsonian on July 4th weekend, and you find out that Clarence Thomas, in your view, misinterpreted your book and name-checked you in that context right there as you're doing that.

Alison Stewart: Yes, and that museum is so moving, and there's so much history, and there's so much difficult history to think about and to process. There's an entire section on school segregation. Some of the people mentioned in my book mentioned in that footnote are featured in that museum. There's just so much to digest and so much to understand about how all that has happened in this country. Then to have this happen, it just really struck a nerve.

Brian Lehrer: What did you think when you had time to read and digest the way he cited you in your book?

Alison Stewart: I felt very upset on behalf of Dunbar's history and Dunbar graduates, because their story is the opposite of what his concurrence is about, and what Justice Roberts, he wrote the main argument. The school was the opposite of that. The idea that one piece of information, which is true, he pulled fact and he cherry-picked a piece of information to support his argument, I think is really-- One, pointing it out is important because it's instructive about context and how important context is. That all of these young men and women who would go on to fight so hard to try to make a life for themselves armed only with the education they got in a segregated system, by the way, is mind-boggling that you would flip that on this head. The idea of just because you're very smart and just because you're brilliant, then the world is going to open up for you, and we live in a colorblind society. These people who went to this school before, I say the '68, gosh, they have lived it. They know that's not true.

Brian Lehrer: Why wasn't Dunbar an example of that? Clarence Thomas would say he was using it to support a position that affirmative action keeps many people from reaching their full potential and succeeding in America. His take on the book seems to be that it wasn't. Jim Crow, I don't think he would oppose Brown versus Board of Education, but it was the all-Black environment of Dunbar in the segregation era and its rigorous demand for excellence.

To this day at the college level, largely Black environments of the HBCUs that do a better job of launching Black Americans into the middle class and economic success in general than what he sees as tortured attempts at integration like at Harvard and other schools that have practiced affirmative action. Why wasn't Dunbar an example of his argument?

Alison Stewart: I think for two reasons. One is the conditions that made Dunbar possible. It was a little bit of a unicorn situation because it was in Washington, DC, and many African Americans were allowed to work in the government and have stable jobs or have support jobs around the government. When you talk about public education, specifically, and you know this, and I think your listeners know this, you're not just talking about the school, you're talking about the neighborhood, you're talking about the economic health of the neighborhood, you're talking about the opportunity of the people who live in the neighborhood. Dunbar had this.

There are different places in the United States where this happened, had this unique position of people being able to have jobs, have stable homes, have two-parent families, sometimes one-parent family, but able to make plans, and able to spend time with their children and invest in their education. Then they had this group of teachers who were very much invested in the students because they also happen to live in the neighborhood.

Then let's talk about why that was. Because of housing segregation. It's not just what happens in the walls, and it's not just the students' ability. That's part of this discussion about affirmative action, and it's not just about the schools, it's about all the other laws that kept people from achieving what they needed to achieve, or possibly could achieve. Another Dunbar graduates they all told me, they all called it a cocoon. Senator Ed Brooke told me it was a cocoon. Wesley Brown, the first Black Raj at the Naval Academy, described it as a cocoon. Then even though they were armed with this incredible education, once they got into it in the real world, it was the real world.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I actually want to play a 42nd clip of you on this show for your book interview in 2013 when you told me that it literally used to keep you up at night, when you were writing the book, worrying that anyone might take it as somehow supporting segregation. Here we go.

[start of audio playback]

Alison Stewart: Oh, my husband and I, I used to have a cold sweat at night that someone would think that. I knew I was going to go out and do press, I was like, "Ask me the worst question you can about this." I would say, "I have to really think this through because I just can't use the word good and segregation in the same sentence." I think it is more about how determined the students were and the faculty were to educate these kids. I also think it shows a little bit of the failure of the early days of integration. I say it's more about-- Because DC didn't integrate it just legally desegregated.

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Dunbar was always all Black, and has remained almost always all Black.

[end of audio playback]

Brian Lehrer: Again, listeners and those of you just joining us, that was Alison Stewart on this show in 2013, talking about her book, First Class, about Dunbar, the High School in Washington, DC that propelled so many prominent African Americans into leadership positions, once upon a time largely in the segregation era. The prospect of a Clarence Thomas doing what he did, was a middle-of-the-night nightmare for you 10 years ago, and now it's a waking reality today. Do you take his opinion to mean he was saying something good about Jim Crow-era segregation?

Alison Stewart: I think that it's interesting, because we had Joel Anderson on who has done the Slow Burn about Clarence Thomas, and how he grew up, and has interviewed his mother, and has gone through all of his memoirs, and it's a really great podcast. One of the things that came out of it was, Clarence Thomas, and I don't want to play armchair psychologist here, but he has said that he has felt that people looked at him when he got to Yale as an affirmative action case, and that that was really damaging to him. It's clear that he-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: That's Thomas's argument.

Alison Stewart: Yes, that's his argument. It's this idea of people not thinking that Black people can be smart enough or can achieve enough, that it just seems to permeate his argument. When I read that, I thought, "Well, why can't any Black students can achieve?" That's not really the argument here, in my mind, or the argument that I want to be associated with. That's obviously that's possible.

It's what happens in terms of opportunity, what happens in terms of access, what happens in terms of support. I don't know what he's arguing. I don't really understand it, to be honest, although it just does seem in some way to stem from something very personal. I don't know if the other parts of that concurrence. It's a very personal back-and-forth with Ketanji Brown Jackson. It's really very personal, I felt, in reading it.

Brian Lehrer: No, it's not twelve o'clock, it is eleven o'clock, even though you're hearing the voice of Alison Stewart, who of course hosts All Of It from noon to 2:00, in the context of her article in HuffPost called, Clarence Thomas Cited My Work In His Affirmative Action Opinion. Here's What He Got Wrong.

Listeners, we can take a few phone calls. You can call her on her own show, but we can take a few phone calls for Alison Stewart here on the content of her book, First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School, and on the HuffPost article.

Any other Dunbar-connected listeners who want to put a little of your own family story into this conversation or on the record here? Has anyone else listening right now ever been misinterpreted or taken out of context by the United States Supreme Court? That would be a needle in a haystack, or in any way that this rings a bell for you, your questions or stories for Alison Stewart invited now. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

Alison, Thomas is as high profile as you can get, but have other less famous people turn the context of your book on its head publicly like this, too, that you've been aware of that make you live that nightmare that you talked about before?

Alison Stewart: Not really. Most of the response was, "Why don't I know the story?" Also from people in DC, that was really telling to me, and I also thought that was really important. Not that if I could write the book over again, I would it's clearly a book by a first-time author and the copy edit, but the idea that some of these stories would get lost, and then they work, but when I first went to Dunbar, the first time I went, and I write about this in the book, that the only history of it was in this dusty old case in the corner. They had a few photos of graduates Eleanor Holmes Norton as a graduate, there was a picture of Senator Brooke.

They literally in broken frames hanging askew in this one corner of the high school. It was just so sad to me. I thought, "Gosh, if we don't write down this history, it will disappear." We can learn from this history. We can learn from the mistakes that were in Dunbar. There was a lot of respectability politics, there was a lot of colorism. I don't want to be completely blind to all of that, but there is so much to learn.

It's interesting because when I would write to people to try to get interviews, people really wanted to talk about it. Valerie Jarrett's father went to Dunbar and he integrated a hospital in Chicago. Who else? Gordon Davis, former parks commissioner, his father went to Dunbar. He gave me a great interview. It's just so interesting to see the tentacles of Dunbar. How it really sent out people into the world who really tried to make a difference who are really dedicated to education, who are really dedicated to opportunity. They used to call them race men and women in the '30s and '40s.

Just the focus, the focus on trying to make things better, was really, really admirable. I just wanted to make sure that came through. I think that's part of why this was so frustrating to see, is because these folks wanted to fight for integration. These folks did fight literally in front of the Supreme Court for integration. These folks were all about young people of color, and I think we can expand that out to other marginalized groups having a chance, having an opportunity, and then doing something with it.

Brian Lehrer: On that point, Justice Thomas, also in that passage in the footnote that I read that mentioned you in your book, he cited the decline of Dunbar as a wildly successful school at preparing Black students for college and wrote, "Indeed, efforts toward racial integration, ultimately precipitated the school's decline." That's the context he wants to emphasize. How do you characterize Dunbar's eventual decline and the reasons for it in the book, if any differently?

Alison Stewart: My documentation of the decline was what I said on your show, as part of why we're having this conversation about affirmative action, you can make something a law, but doesn't mean people are necessarily going to abide by it. The thing that got lost at Dunbar is because there were only a few high schools in Washington DC for Black students. That's something that's also we need to remember, and when you think about that, the idea there are only three or four initially. First, it was only one, and then there were two, and I think it got up to four or five. Two more technical schools. One was the academic school. Dunbar was a magnet school. People came from all over DC, and it was for the kids who were academically minded.

Armstrong was for kids who were more technically minded, but also got a really good academic education. Once that disappeared, and once integration on paper happens, you had white flight, you had people who didn't want to go to school with Black students, you had teachers who had been concentrated and truly cared about students living in the community were sent out to other schools. It's more about the destruction of the focus than it is about the students themselves. Does that makes sense. Did I make any sense?

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Let's take a call, who's actually read your book. Wendy in Springfield, New Jersey, thanks for calling in. You're on with Alison Stewart. Hi.

Wendy: Yes, two points. One, I read your book, and I've been looking for talking about Dunbar for years because I kept seeing it mentioned. I said, "Why is no book about this?" I'm so glad you wrote it. Number two, I went to Yale under affirmative action. My mother worked three jobs so I could go to private school, and I lived and grew up in Harlem. In my English class, I use the word synergistic. I heard later that one of the white members of the class said to his roommate, "She used a word I didn't understand." I said to this person who told me the story, I said, "Well, if he told me he didn't understand the word, I would have explained it to him."

My point is this. If you know that you're smart, you're just smart. It doesn't matter what other people think. What other people think about you, is none of your business. Just be yourself. That's it.

Alison Stewart: I like that advice.

Brian Lehrer: Wendy, thank you very much. Elizabeth in Ridgewood, New Jersey, you're on WNYC. Hi, Elizabeth.

Elizabeth: Good morning. Good morning. I have a two-part question, and your guest probably knows the answer to. Number one, Justice Thomas says he feels that him being Black, had anything to do with his success, gave him opportunities as becoming the justice of the Supreme Court that maybe he would not be afforded if he was not. Number two, that affirmative action has anything to do with his success, that ever in his schooling, that became some kind of a force that helps them succeed. Thank you very much. This is a great program. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Elizabeth, thank you very much. Alison, I don't know if you weigh in. I'll characterize what I believe Justice Thomas has said about that, which is, whether or not he was considered by the admissions committee at Yale, "affirmative action admit," he was perceived that way by students and faculty at Yale. They, therefore, thought he was less qualified than he thought he really was, and just less capable in general.

He has written and spoken about how he feels that that did follow him at the time into his early professional career when he wanted to work in the private sector at high-price law firms, but he thought they looked down their nose at him even though he graduated from Yale as an affirmative action baby, and therefore not as qualified as his on paper credentials would indicate, and that's when he wound up going into government. I don't know if you want to add anything to that.

Alison Stewart: When I think about that, that sounds like [unintelligible 00:23:16]. Like your problem, my problem, but it is our problem now. Look, I have been called an affirmative action case. I'll be honest, I have screenshots from a fellow broadcaster that were sent to me describing me as that. I'm good at what I do. I've worked hard at what I do. To Wendy's point, it's okay, you want to believe that? Fine, great. Good and enjoy your life. I'm going to say something [unintelligible 00:23:47], I feel for someone who feels that negatively about themselves that they have internalized it in such a way.

Brian Lehrer: You are the best by any standard, so you can take that broadcaster's comment as a blurb for any context. Jennifer, in East Harlem, you're on WNYC with Alison. Hi.

Jennifer: Yes, good morning. Thank you for taking my call again, Brian. Alison, congratulations for all that you do. To your notoriety in this case, I did want to ask if you have been able to directly counter this with Justice Thomas because I think it would be critically important to do so, especially because you are a woman.

I also think that a lot of his positioning on many things, including the sexual harassment issues, where he then self-depicted himself as a Black man being lynched. I do think he needs to be taken to task. I think that many people are daunted by that possibility with him because I think he's very masterful in a very insidious way of playing the race card to benefit himself when it's appropriate, and then to denigrate it when it doesn't work, including disenfranchising his own community. I am not an individual of color, so I'm not speaking from that positioning, but I certainly share the view that his hypocrisy is extreme and deeply offensive to the Black community. I'd welcome your feedback on whatever I presented. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Yes, thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Jennifer, thank you. I'm particularly interested in the part of her question that asked if you've gotten to present your objection, personally to Clarence Thomas, or if you have any indication that he's read your article, and takes it seriously or not.

Alison Stewart: Nothing like that. I don't expect that to be the case. I really just wanted the idea that someone would Google first class and Dunbar and my name and that might pop up really upset me a lot. I think this is something we're going to talk about tomorrow on my show, is, I'm about to have surgery, I'm about to go in for surgery, I'm donating a kidney to my sister, and it's going to be great. It's going to be fine, but I think that was weighing in my mind as well, like, "Well, okay, I think I need to write this before I get my affairs in order," and I have been.

I was thinking, I just need to have it written down somewhere that I object to this. It's not right. Everybody think about what you're reading, think about context, think about content. Even within a Supreme Court argument and concurrence, things can be taken out of context. It seems sad to have to say that, but if anybody takes anything away from you, you may disagree 100% of what I've said about this, but know that, that there is a footnote and a Supreme Court argument, which is wrong. Take what you read with a grain of salt, and do your own research, especially with this particular court.

Brian Lehrer: Before we run out of time, and I know, obviously, you have some work to do, prepare for a certain appointment you have at twelve o'clock. You wrote that you have sat on the board at a competitive university, and listened as the athletics department claimed its spots for the freshman class, and so did the legacies. You say there should be a mix of students, first-generation, rural, urban, and all interpretations of the rainbow. I'm reading from your HuffPost article.

It's shocking to me, Alison, that only race, such a defining part of people's experience in this country, no matter what race you are, is the only thing that cannot be taken into account to build a diverse class now while class, gender, zip code, football skills, legacy of your parent going to the school, everything else can. Assuming the competitive university you work with, I don't know if you want to name it, shares your value of having all kinds of diversity, what do you think they're going to do now? Have you been in touch?

Alison Stewart: I believe they're going to stand by their commitment to diversity. I love that the news-- I don't love. I think it's interesting over the news yesterday that Wesleyan is going to announce it's going to stop using legacy as a factor. They join, I believe it's Carnegie Mellon. Carnegie Mellon is doing the same. That's really interesting to me. I just think you need to have diverse classes. How are people ever going to learn about each other, if it's the same people going to school with the same people in the same people's children over and over and over again? It shuts off hope. I think when you lose hope, that's really dangerous. If people just don't even believe that they have the opportunity, or even getting a chance to have an opportunity, I think that's really sad. I think it's really dangerous.

Brian Lehrer: Last question, Alison. You conclude your HuffPost article by writing that all you can do is use your words to set the record straight, but you also have a request of Clarence Thomas, going forward. Do you want to say it out loud here?

Alison Stewart: Yes, I went back and forth on this because I'm pretty no drama, and I'm a pretty sober person. I just tried to be really straightforward. This is where you can tell I was mad. I said, "Please just keep your name and Dunbar's name out of your mouth," the way the kids say these days.

Brian Lehrer: Keep your name, Alison Stewart's name, and Dunbar's name out of your mouth. All right, Justice Thomas, if you happen to be listening today, there is, let's call it a firm request from Alison Stewart. Listeners, her own show, All Of It, is coming up at noon, and as a closing program note, and Alison alluded to it a couple of minutes ago, I will be interviewing Alison again on her show tomorrow at one o'clock about that other intense thing happening in her life right now, her coming kidney donation to her sister. Obviously, this is more directly personal even than being quoted by Clarence Thomas, but it also has meaningful implications for the larger world. We will talk about that. That's, to be precise, at 1:06 tomorrow, right after the one o'clock news on Alison show. Alison, I'll talk to you then.

Alison Stewart: Thanks, Brian.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.