What's Hidden Behind the Pink Ribbon

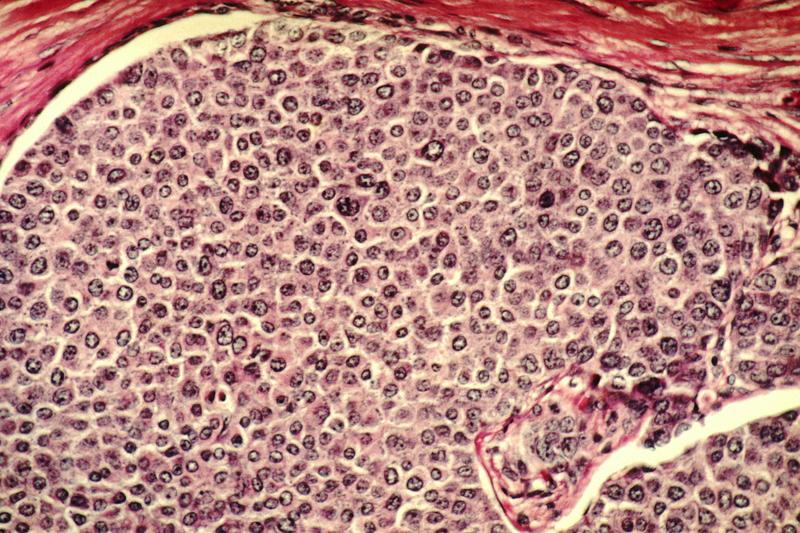

( National Cancer Institute/Wikimedia Commons )

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now we'll close today's show with the recognition that October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Call in for any of you who are dealing now or have at any time in the past, dealt with breast cancer in some way in your life to say, what about breast cancer you'd like everyone else to be more aware of? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. I'll give you one possible topic area in a minute.

In general, maybe you survived breast cancer a decade ago or you're currently dealing with it, or if someone in your family has breast cancer, we're inviting you to call in too. We're taking the name of the month literally for this segment, Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and inviting you to say anything regarding it that you would just like more people to be aware of, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

The one possible topic that I want to throw out, and we'll touch on it with a guest in just a second, is the language that you like or don't like that pertains to you or the disease. The word fighter has recently been criticized. I saw. Do you like, dislike, or have any other reaction when people call you a fighter as you deal with a condition? What about survivor? Is that empowering, stigmatizing? Anything else? What language around breast cancer makes you feel supported or makes you bristle when you hear it?

212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, call or text. Again, more broadly, October, as many of you may know, is breast cancer awareness month. Often we find that awareness doesn't go too deep unless you are someone you know have personally been touched by the disease. Breast cancer awareness often starts and ends with a pink ribbon. Sure the symbol helps spread awareness that the disease exists, but how can it transmit knowledge of the actual lived experience of having breast cancer or what people need with respect to it?

Listeners, with this life experience yourselves, if you are the patient or if you are involved with the patient in any way, we give you the floor on this Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we invite you to make us aware. What's something you want everybody to know about the disease that maybe gets hidden behind the pink ribbon? What about language? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

I want to say that our idea for this segment came from one of our colleagues here at WNYC. When some of you send us feedback, it often goes to our colleague Rebecca Weiss, in the department we call listener services. Apart from her work here at the station, she's the founder of a nonprofit organization, Bob's Boxes, where she sends care packages to patients who've just undergone a mastectomy as part of their breast cancer treatment.

Rebecca Weiss joins us now to tell us about her experience of the disease and what she wishes we all knew about dealing with breast cancer in Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Hey, Rebecca. How weird to not be talking to you in the hallway, but talking to you on the air. Hi.

Rebecca Weiss: Hi, Brian. Thank you so much for having me on the show. It's a bit surreal, but I'm thrilled to be here.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want to take us back into your own personal history at all and how it landed you with Bob's Boxes?

Rebecca Weiss: Sure. I'd be happy to. I was diagnosed with stage 2B breast cancer in spring of 2014. I was 43 years old busy working mom with a commute and two toddlers. I had not been going for my annual mammograms yet. I figured I'd get to it, but I wasn't making it a priority. That diagnosis stopped me in my tracks. Maybe for the first time forced me to put my own health front and center.

Brian Lehrer: Life doesn't stop because of a breast cancer diagnosis, although it can be such a world-altering event. Nobody needs to hear that from me. As you say, you were raising a family during that time. I don't know if you want to say anything about having young children while undergoing treatment. Again, how did the organization Bob's Boxes come to be?

Rebecca Weiss: Yes. I think at first my husband and I thought that we would hide a lot of the fact of what was happening from the kids. They were three and five when I was diagnosed, and four and six when I finished treatment. I thought, it's too scary, it's too adult for them to deal with. A social worker at the cancer center advised me otherwise. She said being honest with them will let them know that they can trust you and that they'll sense something is going on.

Using language that was appropriate for children their age we found ways to share what was happening and gave them jobs. Small children like to feel like they're a part of things and they can contribute. They could bring me a cup of tea or they could rub my shoulder. That helped them take care of me, which I think helped them feel more in control. Around the time that I was finishing my treatment, my father, who was named Bob and who accompanied me to every chemo session and was at the hospital with me after my surgery passed away rather suddenly of a brain tumor. It felt like my own need to give back to other patients or people going through treatment was something I could do in his memory.

Brian Lehrer: Now, I know you have criticisms that we'll get to of some of the usual representation of the disease as a kind of pink-washing, but I'm going to let Missy in Jackson Heights raise what I think is one of the same issues that you have. Missy, you're on WNYC. Thank you so much for calling in.

Missy: Hello Brian and hello to your guest. Longtime listener. I think this is my third time calling, or fourth over a 20-year period. So happy to be on today. I have a very important issue to raise. It's personal. My wife has stage 4 breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer. I am very happy to say that she's doing really, really well. It comes with a lot of questions. First of all, I think that in terms of breast cancer awareness, most women probably know it's a really good idea to get their annual mammogram and do breast exams and all of that for prevention and to get treatment if it is detected.

What happens when it comes back? We didn't seem to get a whole lot of information about that except like, "Oh, it's not likely it's going to come back." My wife's done a lot of research. She has the numbers. I don't have them. I think there's a pretty high chance of recurrence. What do we do about that? If you've survived it the first time around, it doesn't mean that you're out of the woods. What happens now?

We are both frustrated that nobody offered post-screenings, MRIs or CAT scans or whatever. It was only until there were symptoms and it's back. Fortunately, it seems like the survival rates are much better than they used to do. The latest numbers that were out there three years ago, nearly three years ago when she was re-diagnosed, it's on average a five-year chance of survival, which is horrifying.

It seems to be better. There are more treatments, and it seems like as long as she stays ahead of the curve, she has a long life ahead of her, we hope. She's also a brilliant woman with a PhD who knows how to do a lot of research. Often she brings up treatment options to her oncologist, which she says yay or nay on and a lot of times she says, yay. It's just odd that that information isn't coming from her.

Brian Lehrer: It's so much that it's on the patient. Missy, thank you for every element of that story. Rebecca, I know that one issue that relates to Missy's call that you have with our regular discourse surrounding breast cancer is the focus on finding a cure as opposed to managing it. Is that correct?

Rebecca Weiss: Right. I think a lot of the messaging, especially during October is, forgive the phrase, "Save the tatas" or "Get your puppies checked," or things like that, that are cute or intended to be funny or even sexy. It minimizes the true impact of this disease, which can be deadly. I think it makes metastatic patients stage 4 cancer patients feel somewhat invisible. They're not trying to save their breasts, they're trying to live, they're trying to have their lives prolonged. At this point, those therapies that the caller mentioned are glimmers of hope to extend the life of metastatic patients, but they will not be cured. They will be living or enduring this disease for as long as they can prolong their lives. I think if we focus on the word cure, we do so at their expense.

Brian Lehrer: Diane in Bloomfield, you're on WNYC. Hi Diane. I want to note that Diane is not the only person calling with a particular issue that she's going to raise. Diane, you might like knowing you speak for others out there as well. Go ahead.

Diane: Oh, good. Hi Brian. Longtime Listener here. First-time caller. This is very near and dear to my heart because my mother had breast cancer when she was in her early 30s. She did end up passing away from breast cancer when it came back later on in her life, but because she had breast cancer so early, and it's so rare to have it in your early 30s, I was told that I need to go for my yearly mammograms starting in my early 30s. You would not believe how I have to fight with my insurance company every single year for them to cover my screening mammogram.

Every year they deny it. I have to have my provider send a letter of medical necessity. We have to go back and forth. It takes up a lot of time. It's very frustrating. One year I had to get a biopsy because they did find something and I had to reach my deductible first, which was over $1,000 before they would cover anything because I'm under 40 years old. I think it's just a huge issue that we really need to have better insurance coverage for screenings for women who are under 40. It's really important.

Brian Lehrer: Diane, thank you very much. Rebecca, I want to read a text message from a listener, and I'll again just reinforce what Diane says. I'm sure you agree that, especially for people with a family history, it shouldn't be a battle with insurance companies to get covered for screening earlier than some other people. Listener writes on the language question, "Why do I need to be labeled a survivor or fighter? The best language is just to listen to me when I need to be heard, being a great shoulder to lean on." Do you want to amplify that because I know you have these issues too?

Rebecca Weiss: Yes, absolutely. People mean well. They say, "You're so strong, you're so brave, you're going to get this. You got it." There are a lot of days when you don't feel brave and you don't feel strong, and you don't want to let anyone down. You're the hero in the story that they're creating, but it may be false story. I used to have what I would call crying days. Just to say, "Today's a crying day." People would know that I wasn't going to feel the rah-rah that day.

Just to speak to the insurance companies, that's a battle. Obviously, I'm not an expert on, but breast cancer is not one disease. There are different kinds of cancer of the breast. Some are more treatable than others. I think as a community or as a society, we have to remind ourselves that the breast cancer your grandmother had or your sister-in-law had, or even you had may be a different cancer than someone else. What they're facing may be very different in terms of treatment and prognosis, and even just testing than what we're generally thinking of when we think of breast cancer.

Brian Lehrer: We have less than a minute left in the segment, but I'll give one more text message, a voice here by reading it, "Regarding Breast Cancer Awareness Month. I wish people would remember awareness all year and that we are more than breasts." A number of people are writing and calling on that, especially during October. "Pinkwashing is triggering for many of us, especially when well-intentioned people just talk about breasts in a dehumanizing way and forget the women themselves." We've got 20 seconds for a last word, Rebecca.

Rebecca Weiss: Let's remember that we're people with cancer. We're for the most part, women, but also men with cancer. We have families, jobs, and lives that we want to live. Let's be about the person and not about the body part.

Brian Lehrer: My guest has been my colleague, Rebecca Weiss, senior listener services associate at New York Public Radio in her day job and founder of Bob's Boxes, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that sends post-mastectomy care packages to women with breast cancer. Thanks, Rebecca.

Rebecca Weiss: Thanks, Brian. See you in the hallway.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.