What You Need to Know About the Monkeypox Outbreak

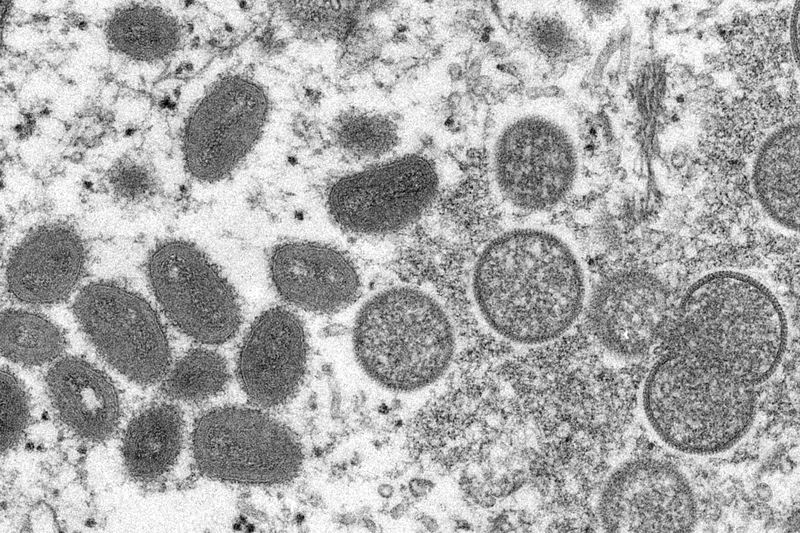

( Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Russell Regner/CDC / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, everything you wish you didn't need to know but you do about monkeypox, what is it exactly? How do you identify it? How do you get tested for it? How long should you isolate if you test positive? Why is the focus on the LGBTQ community if it's not considered a sexually transmitted disease, or is it? With me now to discuss the latest virus in our lives are Joseph Osmundson, a microbiologist, activist, and writer with a PhD in molecular biophysics and author of the recently published, Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things in Between.

We also have Daniel Griffin, infectious disease physician with also a PhD in molecular medicine, researcher at Columbia, ProHEALTH chief of the division of infectious disease, president of Parasites Without Borders, and co-host of the podcast This Week in Virology. He's been on several times as many of you know to talk about COVID, now monkeypox. Between our two guests, we have two PhDs and one medical degree. Thank you both for being here. Welcome, and welcome back to WNYC.

Daniel Griffin: Thank you, Brian. Nice to be back on.

Brian Lehrer: Griffin, could you start by walking our listeners through some of the very basics? What kind of illness is monkeypox? How dangerous is it if you get it? What does it have to do with monkeys?

Daniel Griffin: [chuckles] Okay, I will start right there. Very basic, this is another viral disease. Remember when it was a good thing for the doctor to say, "Oh, it's just a virus." Well, this is just a virus. The reason we call this virus the monkeypox virus and the reason we call this monkeypox as a disease is it was initially identified in some monkeys, some crab-eating macaque monkeys in Denmark in the 1950s.

It really is not a primary infection of monkeys. Monkeys can certainly get it. It is probably mainly an infection of rodents. We've had some issues with prairie dogs here in the US. It can also infect human beings. We'll get into transmission in a second, but how worried do we need to be? A lot of people dust off those old slides and they talk about mortality as high as 10% in the DRC, 2% to 3% in West Africa. Just to go right to current, we've now seen over 8,000 confirmed cases throughout the world, very few deaths.

The way monkeypox is presenting nowadays is, well, think of chickenpox. Think of an area of rash where there are vesicles, which might become pustular. Some people might have fever. The classic that we've talked about where they're all in the same stage of development, that actually looks like it's different. What is it? It's a viral disease. Monkeypox is the historical name. We are usually seeing limited areas of vesicles.

As far as transmission, it looks in general-- I don't want us to make the same mistakes we did with COVID. It looks in general that this is usually spread through pretty significant close contact. Just to give perspective, even in a home where people are in close contact, most people in that home will not end up getting monkeypox if someone is infected. If you're on a plane and there's hundreds of people on that plane and someone has monkeypox and is contagious, it is unlikely that anyone else on that plane will get it.

Then I guess I will finish off here and then get it back to you, Brian, is, why are we describing this as mainly in the gay community, and why are we saying it's not a sexually transmitted disease? Really, it's the close contact this virus has gotten into that population. Through close contact, we're seeing it spread. It's not our classic sexually transmitted pathogen where it's in secretions. Close contact, which actually happens when people are intimate, is really the main way that this virus is transmitted.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your questions about monkeypox. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet a question @BrianLehrer. Joseph Osmundson, I read a Washington Post article last week, which said that there's some difference of opinion on whether monkeypox should be considered sexually transmitted. I know you've expressed some concern about the focus on the LGBT community. Can we get into this? What risk are we taking as the media and as a medical establishment in focusing on that?

Joseph Osmundson: It's a couple of things. Clearly, the epidemiology shows us that in the United States and most other countries where this virus is [inaudible 00:05:16] LGBT people are being the most impacted. We need to be especially aware and our community needs the tools like vaccinations, testing, and treatment to be able to protect ourselves and others. Whether or not it's classically sexually transmitted is an open question. One of the things that I like to remind folks is that we actually don't have very good epidemiology in the endemic region.

This virus is flown under the radar of a lot of the scientific tools we would typically use if it were spreading outside of West and Central Africa. I would argue that whether this is a new mode of transmission being spread specifically by sexual networks is an open question. We don't know whether or not that occurs in the endemic region. Remarkably, for a virus that's been in humans, describing humans since 1970, we don't know whether the virus is in semen or vaginal secretions.

Goodness, if this virus were classically spreading in the United States, we wouldn't have answers to those questions. I would say that other viruses like herpes, which is considered a sexually transmitted infection, also spreads not just through sexual fluids but by close skin-to-skin contact. Well, focusing on the LGBT community is important. We know we have special needs right now, but focusing just on the LGBT community, I think, is a real mistake because we know that we're not an island.

We already see cases happening outside of the LGBT community. I'm super concerned around other sites that have lots of close physical contact like wrestling teams or football teams, massage parlors, and spas. If we are viewing this culturally as largely a gay disease when a wrestling team in Texas comes down with a pox-like illness and it's not on anyone's radar, that could be a really dangerous situation for that community.

Brian Lehrer: I imagine there's also a marginalization concern there. If it's considered mostly a "gay disease," then the rest of society, "majority society" if we want to call it that, can say, "Oh, well, this doesn't affect most people, so we don't have to be too worried about it in terms of an aggressive public policy response."

Joseph Osmundson: That's actually right. Gay folks have a long history, thanks to the HIV/AIDS crisis, of advocating for ourselves. Again, infectious diseases teach us that we are not disconnected from one another, not individually and not as communities. Something that affects people, "Oh, that's just in West Africa," well, infectious diseases teach us again and again and again that that's not the case. "Oh, that's just spreading in the LGBT community amongst gay folks." Well, infectious diseases will teach us again and again that if we don't protect everyone, that puts everyone else at risk.

Brian Lehrer: Griffin, is there a test to determine if you have monkeypox?

Daniel Griffin: There is and it's a very easy test. Basically, take a swab. You swab the area where these vesicles are. You actually need to open that up. You need to be a little bit more aggressive. You're not sticking a Q-tip back into someone's brain like we did in the early days for this other virus that's still circulating. The nice thing and this is a big thing is it took a little while longer than I would like.

Now, you no longer have to audition through the Department of Health to get this done. You can actually send this off to LabCorp, Quest, Mayo, a number of commercial places. It's going to be that molecular testing we're used to. This is a DNA, not an RNA virus. You're just going to take that DNA. You're going to amplify it up. Within a day or two, you're going to get that test result back. We do have a test. We have now, it took a little longer than I like, a commercially-accessible test for this.

I will make a comment and I'm going to echo Joseph Osmundson's comment, is we don't want to make the same mistake we did with COVID. Right now, 36% of the tests we send off have been positive. That means we're not testing enough. What we've been unfortunately doing and this reminds me of the early days of COVID, unless you could show a plane ticket back from Wuhan, China, you couldn't get yourself a test even after we identified that gentleman in Westchester, who probably got it getting to and from work in the city.

We don't really know at this point who has monkeypox because we're only testing a selective population. If we keep with this rhetoric of, "Oh, it's only in the gay community. You can only test the gay community. You should only think about in the gay community," this is going to spread much farther than that. We don't want to pick on those folks in Texas.

I'm not sure if Joseph Osmundson picked Texas, that wonderful state down south. No, we are going to see this in wrestlers. We are going to see this in other populations. If we don't jump on it and move past that bias and do a lot more testing, this is going to continue to spread instead of 8,000 cases right now and approaching 800 here in the US. Those numbers are going to keep climbing.

Brian Lehrer: Boy, you remind us of those very naive, early days of COVID, early March 2020, when the first case, I guess, in New York State was in New Rochelle. People were like "Well, let's close off New Rochelle. Let's close off the business district of New Rochelle. Let's stop people from commuting from New Rochelle to Manhattan," like that was going to do it. For New York City, Dr.Osmundson, as of a few days ago, I read the capacity to test was only 10 people a day. Is that still the case? Do you know?

Joseph Osmundson: It's not. We're expecting testing to shift quickly. Like Griffin, I've been incredibly frustrated with how long this has taken. Colleagues and I wrote an op-ed in May in The New York Times, saying that we need to get tests outside of the CDC available within a week. It took six weeks, so we are way behind. Cases are going to climb that don't represent a new outbreak that just represent catching up on testing the outbreak we currently have.

People need to be aware that over the next few weeks, as we start testing at the scale we've always needed to, the numbers are going to climb in what seems like an alarming rate and it is alarming. I will say that in my community, the gay community-- I'm in New York. I've been speaking to people in San Francisco. Because of this testing backlog, it is taking 10-plus days to get monkeypox diagnoses in San Francisco. In New York, it's a little better, but the community frustration is rising.

The public health folks have been calling this a mild illness in the US. Most people are not hospitalized. We've had no deaths, but people are really in pain. I would say about half the folks I know who've had this virus are experiencing a huge amount of pain. They've had trouble accessing testing and being rejected by multiple providers. Again, having to audition to the DOA to present the perfect set of symptoms, and then if they do get tested, they haven't been able to get access to TPOXX, which is a treatment that is FDA-approved for smallpox. It's very, very difficult to get even for these people who are in pain.

Brian Lehrer: Why?

Joseph Osmundson: Because the CDC and the FDA and HHS are requiring what's called an IND. It basically means that in order to get the drug, you have to enroll in a clinical trial. It takes a huge amount of bureaucratic paperwork to set up a clinical trial. Basically, only major research universities can do this, to begin with. They just have a very limited throughput. It's basically one provider doing a huge amount of paperwork per patient.

They can only do so many patients, so people are really suffering. The drug is FDA-approved for smallpox. There are early indications that it decreases the length of symptoms for monkeypox and people can't get it. No one can get access to vaccine. In this outbreak, we have tests FDA-approved before the outbreak. We have treatment FDA-approved and we have FDA-approved vaccines.

This showed up in the UK six weeks a month before it shows up here, and yet we're in July and people are sick. People are really suffering and our community is feeling like we do not have the tools to protect ourselves to treat people who are unwell and to protect others from the infection. The community outrage is boiling over because most of us know people who have it.

Brian Lehrer: Because you don't have the tools, because you don't have the backup of the public health bureaucracy.

Joseph Osmundson: Exactly.

Brian Lehrer: I want to get to a couple of calls before we run out of time. Thor in Long Hill, I think, has another important question that relates monkeypox to smallpox in a specific way. Thor, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Thor: Hello, Brian. Thank you very much for taking my call. Doctors, thank you very much for the opportunity to learn more. My question is, is a previous vaccination for a pox virus protective against the current monkeypox and is there any particular precautions that should be taken?

Brian Lehrer: Who wants that? Griffin, how about you?

Daniel Griffin: Sure, I'll jump in on that. We do have experience here in the United States. There was a pretty significant outbreak about 20 years ago in the Midwest. Individuals who had gotten a smallpox vaccine previously and people who had not-- There was really no difference as far as the clinical presentation. That distance smallpox vaccine, we think for maybe a number of years, perhaps 5 to 10. We do quote this 85% reduction and 85% protection.

Once you get out to now and for most folks that even did get a smallpox, that stopped in the '70s, so we're talking 50 years ago, that previous smallpox vaccine didn't help probably at this point. Some healthcare workers during that smallpox scare a number of years ago had more recent vaccination. There might be some residual protection. Right now, really, the vaccine is this JYNNEOS. It's a new vaccine. It's really this Ankara-Bavarian, Nordic-attenuated Orthopoxvirus vaccine is the one that is rolling out, as Joseph Osmundson suggested, way too slowly.

Brian Lehrer: You're saying that for anybody at risk because of their potential skin-to-skin contact, football-helmet-to-football-helmet contact, whatever it is that can spread monkeypox, almost nobody is effectively vaccinated because those old enough to have gotten the smallpox vaccine, that would have worn off as it pertains to monkeypox?

Daniel Griffin: I think that is really true. Yes, it's really skin-to-skin contact mainly. There's probably some respiratory and other types of transmission. Yes, I do not think that people are currently protected. That's really this demand that we're seeing for the JYNNEOS, which is really a safe and, we think, very effective vaccine for monkeypox.

Brian Lehrer: Joseph Osmundson, should people seek the vaccine if they think they are in certain risk groups or should this be distributed universally like they've tried to do with the COVID vaccines? How do you see that?

Joseph Osmundson: Yes, we're just really limited on the supply of this vaccine. Some of that is just because this was not an unexpected outbreak. Some other of that was some bureaucratic mismanagement in the federal government that let 28 million doses of this expire without replacing them. Right now, we really are focused on the queer community and people in our sexual networks for being the most at risk and, therefore, in the first tranche for vaccination. I think that's what we need to be doing right now. There is another vaccine, the ACAM2000, where we have 100 million doses. As Griffin has been implying, that really is a vaccine that has a risk profile of vaccinations a whole generation ago. It's a really tough vaccine to administer and manage.

Brian Lehrer: Give vaccines out there first to the currently affected communities?

Joseph Osmundson: That's right.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a question via Twitter. A listener asked, "What about, say, common play areas? I work at a toy store," says listener, "and there are play areas for adults and children to play with the merchandise." Is that a risk, Griffin?

Daniel Griffin: I'm hoping that our improved hygiene and maybe all that hygiene theater that we're continuing should help with that. This does not look like it's as highly transmissible as other pathogens like norovirus, rotavirus, things like that. It really tends to take pretty significant contact. That would be not a zero but a low-risk situation.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to do one more quick question and answer. Actually, you know what? We can't. We're just too out of time.

[laughter]

Brian Lehrer: Joseph Osmundson, do you recommend any other resources for people who want to learn more?

Joseph Osmundson: A community of queer folks in New York is stepping in to fill some of the gaps of the government. We're launching a study called RESPND-MI. You can check that out online. Just to add to what Griffin is saying, surfaces may not be a huge risk here. The shared football helmet as you mentioned or shared clothes, shared bedsheets, shared towels, we know those are sites of transmission. Just things to be aware of for the folks outside of the gay community listening but who want to be aware of the risk.

Brian Lehrer: Joseph Osmundson, microbiologist, activist, and writer with a new book, Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things in Between, and Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease clinician and researcher at Columbia, ProHEALTH chief of the division of infectious disease, and co-host of the podcast This Week in Virology. Thank you both.

Joseph Osmundson: Thank you so much.

Daniel Griffin: Thank you so much. Everyone, be safe out there.

Joseph Osmundson: Yes, indeed.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.