What The NYS Constitution Says About Impeachment

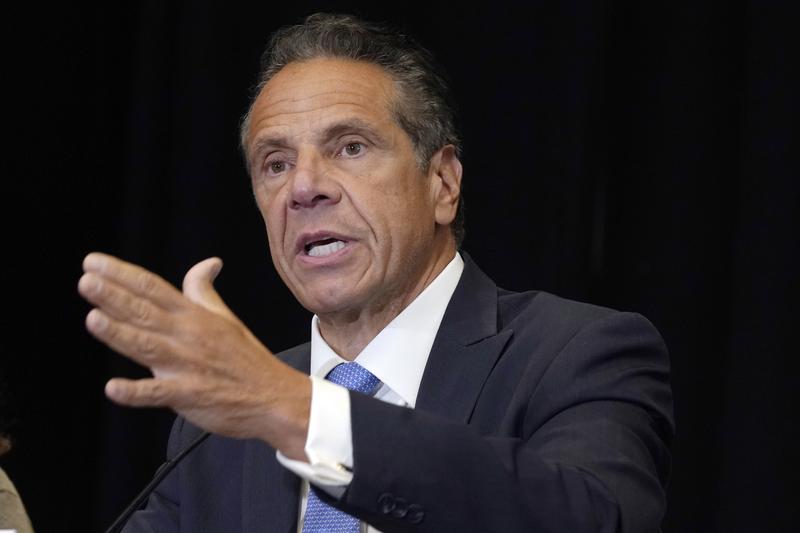

( AP Photo/Richard Drew, File )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We begin today with three developments in the Cuomo sexual harassment allegation since Friday's show. One is that last night, the governor's closest aide, his top aide Melissa DeRosa resigned. DeRosa is mentioned as many times as Cuomo himself is in the Attorney General's report released last week. She allegedly did things like release one accusers personnel file to the press and direct an employee to call and record a friend of that accuser to try to get dirt on her.

In her resignation statement released last night, DeRosa said, "Personally, the past two years have been emotionally and mentally trying. I am forever grateful for the opportunity to have worked with such talented and committed colleagues on behalf of our state." Now on Friday lawyers for the governor gave a press briefing in his defense.

The first one of those the detail making the most news is that when they seem to actually corroborate part of the story from the state trooper who accused the governor of sexual harassment, the lawyer said the governor wanted her on his personal security detail partly because of the way she looked him in the eye the first time they met and he directed that she be offered that job even though it broke the usual seniority rules for who got that prestigious assignment of being on the governor's personal security detail.

Third, the accuser known as executive assistant number one revealed her identity, filed a criminal complaint against the governor for allegedly groping her breast on two supplications one in 2019 and once in November, 2020 and gave a TV interview to CBS. Brittany Comiso described how she first knew she couldn't keep the incidents a secret anymore in March when she saw other women coming forward and described why she had previously not told anyone.

Brittany Comiso: There was a time when between my personal life and this it was too much. People don't understand. It's the governor of the state of New York. He is a professional fighter and I think people should know that it hasn't been easy. I apologize that I haven't come forward sooner.

Brian Lehrer: Brittany Comiso previously known in the Attorney General's report as executive assistant number one, the governor denies that he groped her at all. This Friday, August 13th is now the deadline set by the state assembly for the governor to turn over any evidence that he wants to present for why they should not impeach him. We'll talk now about how the impeachment process works. There are similarities too and differences from the presidential impeachment process like that the state Senate majority leader is excluded as a juror in an impeachment trial, but included are seven New York state judges as it happens at this moment all appointed by Cuomo.

With us now is Christopher Bopst an expert on the New York state constitution. He is coauthor of a book called The New York State Constitution published in 2012 and co-editor of another book called New York's Broken Constitution: The Governance Crisis and the Path to Renewed Greatness published in 2016. He is a member of the judicial task force on the New York state constitution, the New York state bar associations, constitution committee and his day job when he's not pondering the constitution is special counsel to the law firm Wilder and Linneball.

Mr. Bopst, we really appreciate your time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Christopher Bopst: Thank you very much. Great to be here with you and your listeners, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: The governor has until Friday to present evidence to whom exactly?

Christopher Bopst: This would be to the assembly committee that is investigating the impeachment. It would be the assembly judiciary committee.

Brian Lehrer: Then what happens?

Christopher Bopst: Well, then they'll evaluate that evidence and at that point they will decide whether or not to move forward with actual articles of impeachment. From my gathering, from what I've heard from various assembly members who've been interviewed that the assembly is actually looking into not just the harassment allegations, but also some other allegations that could lead to possible impeachment charges, including issues involving construction of the Mario Cuomo Tappan Zee bridge, the governor's use of governor's staff for editing his book and also hiding information about the nursing home fatalities there and the COVID pandemic.

Those are also allegations that the committee is looking into as well. Their breadth at least as they've defined it or described it goes beyond just the allegations that we saw in the report released by the attorney general last week.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that's a lot. We may be at this for awhile. I mean, we know from the Trump impeachments that the usual procedure is for the house judiciary committee to call witnesses before taking a vote on whether to recommend impeachment to the full house. That's where those hearings are where the public met, all those people like Colonel Vindman and ambassador Marie Yovanovitch, Fiona Hill. Just listeners when you thought it was safe to forget about those people, all those people. Will the assembly judiciary committee be holding hearings like that in this case and maybe on these multiple topics,

Christopher Bopst: They may, certainly that's, an option. I think in all candor, they probably are hoping that by going through this process and once it becomes apparent that there--[unintelligible 00:06:23] the votes to impeach and the votes to convict in the state Senate. I think it's their hope that the governor will resign and they won't have to go through drag the state and their party through that process.

Ultimately, in the event that he chooses to fight on as he's expressed an intent to do at least till now, then they could call witnesses. There could be a lot involved here but I also think that it's a little different than the Trump impeachments in the fact that, the impeachment trial involving the one where he was still in office, the Ukraine issue, that was a little bit of political theater.

I don't mean that in a negative way in the sense of that, I believe that the Democrats thought that getting this evidence in front of the public would make a more compelling case and would also undermine the president and in some aspects, I think the did accomplish that, not enough to move the needle in the Senate say for one vote and Mitt Romney but in this case you're not going to want the Democrats who are going to be doing the impeachment since they control both houses of the New York state legislature are not going to want a protracted process that drags one of their own members more through the mud.

Again that's not making any comment in terms of the merit of the allegations. I think the report released by the attorney general was pretty damning and very well corroborated conducted by some very established and prestigious law firms so they did their homework. It wasn't a sham investigation by any stretch of the imagination. The Democrats in the assembly are not going to want to prolong this more than necessary. It's going to be a stain on their party and they're going to want to move it along as expeditiously as possible with the ultimate hope that they probably don't have to go through with it.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that's an interesting political analysis that the assembly might be shy to engage in that kind of political theater even if it helps make their case against the governor because they all may suffer as Democrats. At least for democratic majority in the assembly, all may suffer as Democrats by rubbing off on them.

Listeners, we invite questions. The New York state impeachment process now underway for New York state constitution expert Christopher Bopst or any of the recent developments from, or since the Attorney General's report that might be relevant to him as a legal expert. 646- 435- 7280, 646-435-7280, or tweet your question @BrianLehrer.

Let's keep walking through this process Mr. Bopst. Then if the assembly, the full assembly does vote to impeach there would be a trial in the state senate, again like there was in the US senate for the president, but what's this rule about the majority leader not getting a vote. Listeners, imagine if all the senators except Mitch Mcconnell were allowed to vote on removing Trump, and then we get into the seven judges from the state Court of Appeals who are also included as jurors, in addition to the 62, I think it is, senators, but why is the majority leader excluded?

Christopher Bopst: The majority leader is excluded not by virtue of her office as the majority leader per se. She's excluded because she is also the temporary President of the Senate. The lieutenant governor is the President of the Senate, but she only has a vote in breaking ties if there is procedural issues. She can't vote on legislation, but she's the President of the Senate. The temporary President of the Senate is Andrea Stewart-Cousins.

Under New York law, under New York State Constitution, she is actually third in line to the governorship. It goes governor, lieutenant governor, then temporary President of the Senate is third in line. The US Constitution, the Speaker of the House is actually third in line after the vice president. The reason she's not allowed to participate is because she's in the actual line of succession as the temporary President of the Senate.

Again, it's a little different in the US Senate, because the actual line of succession doesn't go to the majority leader, it actually then goes to the same thing, the President Pro Tem of the Senate, after the speaker, who is usually the longest-serving senator in the party holding the majority. It's a little different in terms of those dynamics.

In New York, you have what's called the court for the trial of impeachment. That consists of the state senators, in this case, only because it's a gubernatorial impeachment, Andrea Stewart-Cousins cannot participate, so you have 62 of the state senators. Also in the court for the trial of impeachment, [unintelligible 00:12:00] mentioned the seven judges on the New York Court of Appeals, which is New York's highest court. They also participate as well.

If everybody is present, you would have a 69 member court, and you would need a two-thirds majority or 46 of those members to ultimately remove the governor from office.

Brian Lehrer: Where did the seven judges from the state Court of Appeals, and that's for listeners who don't know, that's the highest court in the state, that's the equivalent of the Supreme Court for the New York State Constitution and other things that come to the state's highest court. Seven members Court of Appeals, as it happens right now, I believe they've all been appointed by Governor Andrew Cuomo. Why do they get to sit with the lawmakers?

Christopher Bopst: It's believed that it would provide a more of a judicial feel to the process. Again, if you look at the actual impeachment article in the New York State Constitution, it's actually in the judicial article. It's article six of the New York Constitution, which is the judiciary article, and then it's section 24, and it's the court for the trial of impeachment. It's been in existence that way since the constitution was drafted up in 1894. They've participated in that process. That gives more of a multi-branch element to it, which in some ways could be useful.

In a case, for example, where you see a governor, who is of a different political party than both the houses of legislature, if you were to get say, a rogue legislature that would want to impeach just for political reasons, not because there was an actual offense committed or an impeachable offense, then presumably, the judges on the Court of Appeals would provide more of a leveling spirit to that and add a more judicial bent to it, and presumably keep the court from getting off the tracks, if you will. It does provide more of a judicial perspective, a little more of expertise in terms of how trials generally are conducted.

You saw in the Trump first impeachment, you saw you had the chief justice, John Roberts of the United States, who was conducting the process, and then you had the senators who were also trying to advise him on what to do because these things don't happen very often. Having a full bench of judges with experience conducting trials, and handling appeals would provide more of a judicial perspective and make it a little more court-like than a political process or a pure political vote, like any other vote in the New York State Senate.

Brian Lehrer: Right. I see why on paper, that would be a good thing, taking it a little bit out of the realm of politics, but the seven Court of Appeals judges sitting right now were all appointed by Cuomo. Do you as a practicing attorney and a constitution expert, state constitution expert know these individuals well enough to have an impression of how independent any of them will be or that the group will be?

Christopher Bopst: Well, I think that one doesn't get appointed to a court, whether it be the US Supreme Court, whether it be the New York Court of Appeals, without having an expertise and an independence that goes with the process. I know, for example, the nominees to the court go through an extensive interview process through the judicial nominating commission. Ultimately, they're also approved by the State Senate.

There's an extensive process one goes through to become a member of the New York State Court of Appeals. These are judges that have excellent reputations, the competition for the seats, and we saw there were recently, a couple of vacancies filled on that court. The competition that has gone through in terms of the number of candidates, the number of interviews that are conducted, and ultimately, the process that leads to one being appointed to that office is a rigorous process. The people who are on that court are very high caliber, and certainly are able to go in and deliver an independent judgment.

The other thing I will tell you is, and this is more of a speaking, practically in terms of the overall history of the state, is that Court of Appeals judges serve 14-year terms. The longest-serving governor in New York's modern history was Nelson Rockefeller, who got elected for four terms and ultimately resigned roughly at the end of his 15th year. The idea that a Court of Appeals judge would be up for renomination by the same governor is not the reality of it. In most situations they either and there's a mandatory retirement at age 70.

The judges that are sitting on that court at any given time, if they don't age out, and come up for reappointment because they were appointed before age 56, I don't think there's been an occasion in history where a judge initially appointed to the court by a governor was reappointed by the same governor or came up for reappointment in front of the same governor. In fact, I know there hasn't been because they didn't start appointing judges until 1978. We haven't had a governor who served more than three terms since then.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Maybe they would come in with some underlying pre-existing sympathy toward him, but it's not like their jobs are on the line or he holds any power over them at this point. One thing that's been getting some press is that unlike high crimes and misdemeanors as the standard for impeachment at the federal level, there is no language describing an impeachable offense in the state constitution. How will legislators determine what makes any of these charges actually impeachable?

Christopher Bopst: It's really wide open, and large part is what the legislature deems to be an impeachable offense, so it's very open-ended. That's one of the criticisms of the article is that it doesn't provide that definitive guidance on what is an impeachable offense and what isn't. We discussed that actually, in our book, The New York State Constitution, which was referenced in the introduction, that there really is no definition.

Earlier state constitutions did specify, for example, [unintelligible 00:19:43] corrupt conduct, and high crimes and misdemeanors, but the 1894 constitution which we're currently operating under, does not define that. It's not as clear. There are different-- There's actually a-- Step back for a second here. In that aspect, really what an impeachable offense is rests on what the assembly and what ultimately the State Senate decide is an impeachable issue.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute with New York State Constitution expert, Christopher Bopst. We'll start taking your calls. Ingrid in Basking Ridge, I see you, you'll be first. We'll also get into his legal analysis, at least a little bit of the criminal charges that were filed against the governor by one of his accusers on Friday, and we'll hear a clip of one of the governor's lawyers defending against that. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue talking about the impeachment process in New York State, which is now underway against Governor Cuomo with New York State Constitution expert, Christopher Bopst and Ingrid in Basking Ridge, you are on WNYC. Hi, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Hi, good morning. Thanks for taking my call. I think this is such an interesting opportunity for the country to see a democratic group impeaching a democratic leader. What a different story than despite overwhelming evidence against Donald Trump, the Republicans choosing not to. It seems to me there's a much bigger likelihood right now that the Democrats are going to want to get this over with and go ahead and impeach him and people can see the system works.

Brian Lehrer: Ingrid, thank you very much. We get a lot of calls around this idea Mr. Bopst and there are different wrinkles to it. I'll follow up with a different one than the caller brought up. Ingrid is saying basically, the system can work if a party is willing to impeach the executive from their own party if they think he did something wrong.

Christopher Bopst: Well, it's true in the sense that impeachment is a process that is is designed to remove somebody from office. It's a very serious process. In New York, I think we've had a total of since 1894, three or four impeachments. You had Governor Sulzer, who was the only governor to have been impeached and removed from office in 1913. You had several small handful of judges who've been impeached and removed from office. It's not a process that's used-- Well, actually say it a different way. It's a process that's used sparingly and rightfully so.

Taking somebody out of an elected office is serious process, regardless of what political party it is that holds that office and what political party it is, that is in the legislature, bringing those charges. It is very rare that you see an impeachment brought by a party in power in the legislature against an executive of the same political party.

I also think that in this case, you have a political party and the Democrats that have really made women's rights and women's issues a real centerpiece of their agenda for decades now, where they have implemented different legislative changes. They've gone ahead and pushed forward. You see that with both events at the national level, you saw with the Brett Kavanaugh nomination, with the allegations brought by Christine Blasey Ford, and what the response was to that. You see it with Kirsten Gillibrand pushing forward with the sexual assault process in the military to reform that.

You saw Al Franken resigning under pressure from his party after some photos came out that were not particularly appropriate. You see that, you see that they've made that an issue. It's sexual harassment in New York State. If you're a private employer in New York State, you have to provide sexual harassment training to your employees. That was a result of a democratic legislature after several scandals and both the legislature itself as well as the Me Too Movement saying, "We in New York care about sexual harassment. We care about having people," and again, it can be done to men as well. Men are victims of sexual harassment as well but the overwhelming majority of cases are men against women harassment, and we as a state have said that we are not going to tolerate this.

Governor Cuomo himself in 2013, sent out a tweet about zero tolerance for sexual harassment. Now to not take action would really undermine their credibility as a party. That's the problem you now have for them as a party and how this plays out. For a second, I shouldn't say forget, but, let's put to the side that justice should be served in this but also just as a pure political calculus, how's that going to look, if you have taken the position that, "We care about women, nobody should be harassed at work but now, this is one of our own members so we're not going to take action."

That's why you've seen such a-- and I believe a desire for justice, is why you've seen such a visceral response from so many of the prominent Democrats both in the state and nationally that something be done.

Brian Lehrer: Ingrid, thank you for your call. 646-435-7280. Allen in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi. Allen.

Allen: Good morning. My main point to call this morning is more of a process than about Cuomo. I just learned for the first time that we don't have something like a high crimes and misdemeanors substantive standard as we have at the federal level. I learned last week that the governor can be removed during the pendency of impeachment even before there's a conviction in New York. The temptation of nefarious forces to manipulate these loopholes in our system to try to effect a coup for the wrong reasons are great. We already know that we've had people in the 2016 and '20 elections, ginning up the internet to drive memes that make things happen more rapidly.

We don't know if that's happening here but we shouldn't be on the lookout for it. I'm just saying that, since there are no clear standards, like high crimes and misdemeanors, which is big enough as it is, we ought to be really careful to make sure that we don't have an impeachment that's driven purely by popularity polls, by media hype, and really try to find some strong hard edge criteria that all these seven Supreme Court of Appeals justices would agree with.

God forbid, we should have a preponderant majority of non-court Senate voters to impeach against the better judgment of all of those judges, this would be a purely political circus. [unintelligible 00:27:44]

[crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: That would be interesting. If it comes out that way, where all the judges in the Senate jury, or adjacent to the Senate jury voted one way and the majority of senators voted the other way. Allen, thank you for raising those important points. Christopher Bopst, what do you think? Do they set a precedent here since there is no language in the state constitution for what constitutes an impeachable offense? Do they set an important precedent for the future here, no matter what they do?

Christopher Bopst: Well, I think we're assuming for the time being that ultimately, this is going to go to an impeachment trial, which, as I noted earlier, I think that as these things continue, you're going to see more and more of a drumbeat for the governor to resign, you're seeing it now. One of his top aides has resigned. You seeing he's already lost union support, the political leaders in the state, Carl Hasty and Andrea Stewart-Cousins have both come out and said he can no longer govern effectively, and he should resign with the implication being that if he doesn't resign, we're going to take the necessary steps to get him out of office. I think there's not going to be-

[crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Maybe you're predicting the governor is going to resign. On the other hand, there's not just been a drumbeat for the last week, there's been a whole percussion section, and yet he's digging in for a fight. Who knows? Maybe Trump is his example. I don't know.

Christopher Bopst: You see, well, again, there's differences in terms of what the political power structure is, and I'll just make a brief sentence and then I'll get back to Allen's point because he deserves a response, of course. I think that when you look at what happened with the Trump impeachment, Donald Trump knew going into that trial, that he was safe. He knew that there was no way he was going to get 16 or 17 Senators to defect and vote to convict and remove him from office. He had so much political power at his fingertips.

All he needed to do was go ahead and write out and say, "Senator so and so vote against me. What a bum kick them out of office." Then that Senator would be primaried and would probably lose his or her seat. We've seen that. We've seen him do that with politicians where he would send out a tweet against somebody who served in the house of representatives for years sometimes decades. Next thing that person's primaried they're gone, their career's over.

The governor of New York right now does not have that degree of power so you're going to get a state Senate that's not going to be afraid that if we vote against him that there's going to be repercussions down the line. I think again he has to say, "Do I want to subject myself, my family, my party, my state to a trial?" Now maybe he will. I'm not going to predict that he will resign, I'm just going to say there will be louder calls, they will be more insistent, there will be more private meetings and ultimately that may change his mind.

[crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. You want to answer Allen's specific question.

Christopher Bopst: I want to answer Allen's point. Yes. There should be a standard and I think you will see that. I think you will see that because I think what will happen is that the state legislature will realize that there is this loophole or not loophole, this void in the state constitution and there is no real definable conduct. I think you will see there will be proposals in the state legislature to amend the state constitution.

In order to do that, you need to have an amendment or a concurrent resolution passed by both houses of the legislature in two concurrent sessions within election in between so it would not surprise me to see them move to close that loophole. Do I think that there's going to be a situation where you're going to get a purely political impeachment that's going to or nefarious impeachment that is going to be not based in evidence that's going to be designed just to remove somebody from office. I don't think you're going to get two thirds of the court for the trial of impeachments to go along with that.

What makes it a little bit more assuring is that even if you had both houses in the state legislature controlled by a party different than the governor in the end even if they impeach that governor, they're still getting somebody of the same political party to take over. It's not like you're going to say, "Okay, we're going to go ahead and impeach the governor and then we'll get one of our own party in there." You're going to still get somebody who's that same political party.

I think the likelihood of getting a two thirds of the voters in the court for the trial of impeachments to go along with the no good faith impeachment that's not going to happen. But I do think that it should be more defined. I think there should be a better definition of conduct and often hopefully this brings about that change.

Brian Lehrer: That's pretty interesting. We know at the presidential level there's never been a successful impeachment when Congress was controlled by the president's own party or the Senate was controlled by the president's own party. The Senate which holds the trial and that was true in the case of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton and Donald Trump so you're laying out all the ways that this is different.

Do you think that the vagueness of the impeachment standard gives Cuomo a way to wriggle out through an opportunity to challenge any of the impeachment proceedings in court and fight on that additional front, the legal front or does the vagueness give the legislature a wide open birth for deciding how to make the rules?

Christopher Bopst: The ladder. In fact, with the impeachment of Governor Sulzer, the only Governor who was removed from office his charges actually involved conduct that took place before he even assumed office. In that case he was impeached, he was removed from office so there's a historical precedent as to how these things are designed to play out. With regard to challenges in court, impeachment is for the most part a political question a political process and so courts historically have been loads to interfere in that process because it is a political process.

There's a doctrine, you see it at the federal level a lot where it's called the political question doctrine which essentially says if there's a an issue that the constitution specifically reserves to a different branch and puts in their hands then the courts are not going to interfere with that. That's what and historically the federal courts have treated impeachment in that regard as, "Look, that's not our ambit." There's a process for that.

For example, if you had a president who was impeached and didn't believe that the standard that the high crimes and misdemeanors were met the US Supreme court would probably take the position that that's up to the Congress to determine what a high crime and misdemeanor is and there's even debate during the time the constitution was adopted as to whether you even needed a crime. In fact I think there's a famous clip by Lindsey Graham saying back when Bill Clinton was being impeached saying, "You don't even need a crime for an impeachment."

If you had a president who was impeached and he went to the Federal court and said, "Well, I've been wronged here, this is an illegal impeachment." The precedent in that has been that the courts would say, "Well, that's the political process. It's been put in the hands of the of the law." Again, I'm certainly not going to predict what the courts of New York would do but I think that you have a process that even accounts for judges in the process. I think the chance of a court getting involved in that it would be a difficult argument for Cuomo's team to make.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, Judges involved in the process that certainly would be a bizarre spectacle if Cuomo is suing the state Senate triers of him of his impeachment case and those triers included the seven judges from the state Court of Appeals who would hear that lawsuit that he brings. Well, hopefully we won't get to that point one way or another. Before you go, let me get your take on one of this weekend's developments from a legal scholar's point of view.

The former executive assistant number one. Now she came out with her name Brittany Comiso filing a criminal complaint with the Albany county DA over Cuomo allegedly groping her breast on two occasions the governor denies this. Let me give you one piece of evidence that has surfaced on each side and get your take. She says she told people in March when other women started coming forward about the governor about these alleged incidents from 2019 and 2020 because in March she couldn't hold her secret in anymore after hearing others come forward.

Apparently, there would be some people who would testify that, yes, she told me about this in March and she was really upset. Then on the governor side, here's a clip of one of his lawyers Rita Glavin speaking Friday trying to cast doubt on Ms. Comiso's account of the alleged groping when she was working with the governor at the governor's mansion.

Rita Glavin: Emails that she sent while she was at the mansion reflect that she was joking while she was there, she was eating snacks and she even offered to stay longer at the mansion when her work was done.

Brian Lehrer: How much do you think things like those emails serve to exonerate the governor? How much are they irrelevant to the charge? Also the contemporaneous telling to other people of her experiences by Ms. Comiso?

Christopher Bopst: Well, I think that you have a situation where when somebody is the victim of a of a harassment or potentially even-- Well, I should say that somebody's the victim of unwelcomed or unconsensual sexual contact and that in and of itself can provoke a series of different reactions. I believe that there's been an issue about and I think that- I believe that it's been rebutted that the date that Ms. Glavin was talking about was the actual date that this had happened.

I think that the response from the Attorney General's team, I believe, has been to say, "Well, she did not recall the exact date it happened," so you can't measure it up with that degree of date certainty. With that being said, the fact that somebody and assuming for the purpose of this discussion that what she said happened happened. You can't necessarily predict or gauge exactly how somebody in that situation should react. I think that sometimes we, as a society impose a burden and it's not right.

There's a societal burden oftentimes that's imposed upon people who are victims of unwelcomed sexual conduct that, "Why didn't you immediately go to the police? Why didn't you immediately go to somebody and report it? Why wasn't the next text message you sent a one that said this happened A, B and C." I think that things don't work that way. The way humans respond to traumatic situations. It's not formulaic. It can't be predicted in such a way.

We look at these items and we say for example, the governor's team, if it turns out that's the date that it happened would naturally try to point to that as well, say this didn't happen because if it had happened, then there would be that she would be in distress and she wouldn't be sending these kinds of messages. At the same time, there's also can be a situation of, "Oh my God, did this really just happen?" Almost trying to almost normalized one's conduct to try to almost, I guess almost wish that it hadn't happened but it did happen.

Again I'm not saying it definitely did happen in this case. Although the Attorney General's report did provide a lot of corroborating evidence and ultimately that's why you have trials. I think to just look at her conduct while she was at the mansion and say, "Well, there you go. That means it didn't happen." I think that you can't automatically do that. You can't completely discount what she's saying happened because of that.

Brian Lehrer: Last question and we get lots of versions of things like this so much pertaining to Trump that are parallel or not to these, each individual development pertaining to Cuomo, listener tweets. Why is no DA looking into the dozens of sexual assault allegations against Donald Trump? Do you know the answer to that?

Christopher Bopst: I don't know the answer to that but I do know that a lot of the allegations against him were older allegations. There may be statute of limitations issues with regard to those allegations, as opposed to here we're dealing with things that happened allegedly happened within the last couple of years. The statute of limitations is probably more available-- makes up a criminal prosecution more available than it was for a lot of the allegations against president Trump. I think that that's probably the main reason why a lot of these things went on unprosecuted was just that they were just too old by the time they came up, a lot of was things he did years prior when he was involved.

In fact that's why you see the current civil lawsuit that's been brought against him is, basically, it's not even for the assault itself, it's for based on his defamation for lying or for allegedly lying and denying the assault. The statute of limitations often serves to block a lot of these issues years later. Now, some states are changing their statutes and in cases involving sexual offenses to make them easier to prosecute or make them more prosecutable for a longer period of time but still a lot of times you brought up against the statute.

Brian Lehrer: By the way this just in, according to the associated press, "Roberta Kaplan a leader of the group Time's Up has resigned. The AC says over fallout from work advising the Cuomo administration on harassment allegations." Roberta Kaplan out from Time's Up as a result of her work with Cuomo, I believe from the Attorney General's report, she was involved in the effort by the governor's office to discredit Lindsey Boylan. I think she reviewed a draft of the disparaging op-ed about Boylan they had circulated according to the Attorney General's report. There's that development.

We thank Christopher Bopst expert on the New York state constitution. He is coauthor of a book called The New York State Constitution and co editor of another book called New York's Broken Constitution: The Governance Crisis and the Path to Renewed Greatness. His day job when he's not pondering the constitution is special counsel to the law firm, Wilder and Linneball. Thanks so much for joining us and all the analysis that you gave us this morning. We really appreciate it.

Christopher Bopst: Thank you very much, Brian. It's been a pleasure.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.