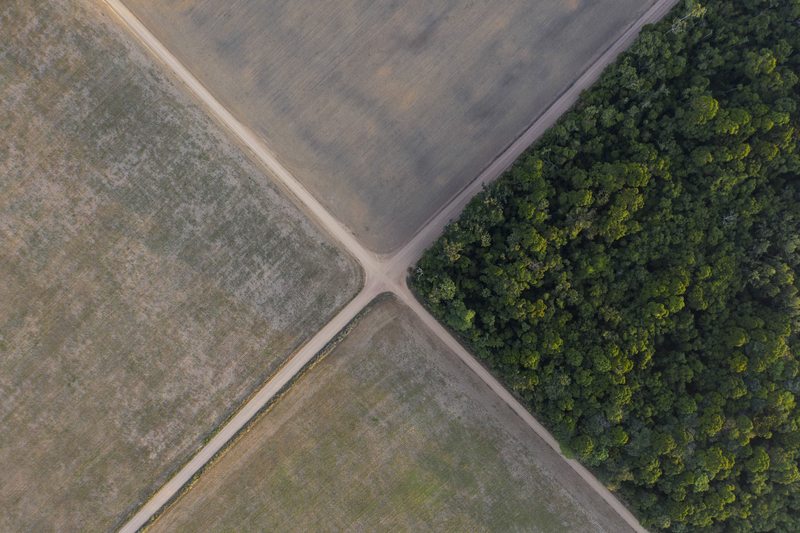

What Bolsonaro's Re-election Could Mean for Climate Change

( Leo Correa, file / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Now, our climate story of the week. This week news from the Amazon, not Amazon, as in Jeff Bezos, but the Amazon, the rainforest in and around Brazil, sometimes called the lungs of planet Earth. We want to talk about the state of the rainforest right now. A widely reported stat is that deforestation proceeded at the fastest pace on record in the first quarter of this year. We want to talk about the politics of that within Brazil, and what can be done to help both the people there and the rich biodiversity of the world's largest tropical rainforest.

Joining us now is Brazilian journalist, Manuela Andreoni, writer for the New York Times Climate Forward newsletter and a former Rainforest Investigations Fellow at the Pulitzer Center. She is based in Brazil and joins us from there. Manuela, welcome to WNYC. Thank you so much for coming on with us.

Manuela Andreoni: Hi, thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Where in Brazil are you today, just for people who know the country?

Manuela Andreoni: I'm in Rio de Janeiro, where we had the Olympics in 2016.

Brian Lehrer: Last year, you wrote that the Amazon deforestation had reached a 15-year high. That just since Jair Bolsonaro became president in 2019, the forest had lost an area bigger than the country of Belgium. The stat I saw and just cited just for the last three months is an area the size of New York City being deforested. I saw that stat on Reuters. Is this a direct result of Bolsonaro's policies? If so, which ones?

Manuela Andreoni: Yes, absolutely. Bolsonaro's actual policy, he hasn't been able to change any major laws. His policy is basically weakening law enforcement. What you have to understand about Amazon deforestation is that it's basically criminal activity. When you weaken law enforcement, it skyrockets. This is what he has been doing basically. He's underfunding these agencies or putting people who are connected to agribusiness or mining on top jobs and environmental agencies. He's firing public servants who are doing, for example, big operations to stop deforestation. This is the major policy that is driving this shift.

Brian Lehrer: Wait, it's illegal in Brazil to burn or cut down rainforest?

Manuela Andreoni: Well, it depends. Brazil has a lot of protected areas, I believe it's something like 40% of the Amazon. It's illegal to deforest in those areas. In private areas, farmers have to maintain 80% of their farms preserved. A lot of the deforestation is illegal. We also have to have permits to deforest, so 99% of deforestation that happens in the Amazon is illegal.

Brian Lehrer: Is most of the deforestation for cattle ranching and for logging?

Manuela Andreoni: Most of the deforestation is actually for land grabbing. Deforesting is a way to claim a piece of land so other people know that that's yours. You can later use that piece of land for cattle, which mostly people do. Then later that could [unintelligible 00:03:49] farm, for example. The deforestation that happens for logging, is more likely called degradation because it's a selected number of trees. Sometimes that doesn't even show up in the statistics of deforestation, because it's a different way to harm the forest.

Brian Lehrer: Who benefits and who loses among Brazilians from deforestation? Let's leave the climate science aspects of this aside for the moment, and we'll get to them, but I could imagine a politics where Brazilians as a whole would say, "Don't make us responsible for being the lungs of the planet at the expense of our economy and not yours," but I imagine it's more complicated than that. Yes?

Manuela Andreoni: Yes, actually, 90% of Brazilians want the Amazon protected. Very few people actually benefit from deforesting it. There are actually studies that show people migrate from deforested areas a few years later because the wealth it creates vanishes very quickly. The people who are benefiting are very few. They're the cattle ranchers or the farmers. What happens though, is because the Amazon is such a cash-poor place, there are no jobs there, the economy is very weak, so a lot of people are forced to be part of this illegal industry. They're forced to go mining because they don't have other options.

It's not that they want it to be this way, it's that sometimes there's no option. Most Brazilians believe that the government should do more to protect the Amazon, but also to create an economy that favors a standing forest, rather than the destruction of the forest.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take some phone calls. Anybody connected to Brazil want to call in about deforestation in the Amazon, or anyone who just has a question about it for our guest, Manuela Andreoni, from the New York Times Climate Forward section. 212 433 WNYC, 212 433 9692, or a tweet @BrianLehrer. Here's a clip of President Bolsonaro. This was in a speech to investors in Dubai. He said the Amazon doesn't catch fire because it's humid. It doesn't catch fire. I said the right words, but I didn't say it right. He says it doesn't catch fire. It's too humid to catch fire. The forest is doing just fine. Let's hear some of this. I think this is in Portuguese, and then we'll get a translation.

President Bolsonaro: [Portuguese language]

Brian Lehrer: I have the translation in front of me, but do you want to do it, Manuela?

Manuela Andreoni: Well, you can do it. Translating sometimes is a bit hard.

Brian Lehrer: Okay. It's hard on the fly like that. You only heard it once. He said the attacks that Brazil suffers when it comes to the Amazon are not fair. There, more than 90% of the area is preserved, it is exactly the same as when it was discovered in the year of 1500. You want to fact-check that even if you don't want to translate it?

Manuela Andreoni: Well, the Amazon actually has lost some 20% of its original cover at this point. I'm not sure if this is just the Brazilian section or the whole Amazon because it's eight countries. What's happening is actually the deforestation is making it less humid, especially in the south of the Amazon, it is catching fire. It's becoming a lot drier, and that's what is destroying the forest.

When you go to the Amazon, sometimes people are like, there are so many trees. It's not possible that we can destroy it all, but what happens is that by destroying it, you're actually changing the ecosystem and making the forest become something else. There's research that shows that some areas of the Amazon have actually started to emit carbon rather than sink it because it's becoming so much drier. This is the transformation that is happening, and some people say, some research shows that there will be a point where we will have destroyed enough of the forest that it will no longer be a forest. That is what people are very concerned about.

Brian Lehrer: What are the climate implications of destruction of the Amazon rainforest? It's almost an abstraction, I think, for most people because we don't see it directly. Our heads get wet when it rains, we know that. Can you quantify the impact of something like an area the size of New York City worth of forest going away every three months in climate terms?

Manuela Andreoni: Basically, what you're doing is you're releasing a bunch of carbon in the atmosphere that is contributing to making our planet warmer. When forests grow, what happens is they get all that carbon out of the atmosphere, and sink it in the tree, or in other plants. The forest is a carbon sink because there are so many trees that have carbon in them. When you deforest, you're actually basically taking your chest of carbon and throwing it away.

The forest is also like a climate regulator of sorts. Scientists prefer for us to call the Amazon the world's air conditioning system. It cools the world down. For example, we have been seeing here in the region that Amazon deforestation is tied to droughts because the Amazon actually generates a lot of rain that irrigates Brazilian and Argentinian agriculture. This is the importance of the forest. There are several roles, climate roles that it plays.

Brian Lehrer: Cleosa in Queens, you're on WNYC. Hi, Cleosa.

Cleosa: Hi, how are you? Hey, I just heard what the topic was about and since I'm Brazilian, I was just-- Bolsonaro was saying that 90% is preserved. I really, really hope that's the case, but the thing is I need more details to really know if that's true, because when I follow up the thing, it's so many devastation in part of the Amazon forest that's like, what are they doing? I just got to keep follow out with my Brazilian fellows.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want to say in your own words why the Amazon is important to you or to Brazil?

Cleosa: Well, it's important for the world, not for me and Brazil. I think it's a huge impact in humanity and, like you say, we need that and to preserve it, we have to do everything that we can to avoid more devastation the forest.

Brian Lehrer: Cleosa, thank you so much for your call. Marcus at LaGuardia Airport, he says, you're on WNYC. Hi, Marcus. You're on the air before you're in the air.

Marcus: Good morning. I just want to make a few comments. I'm also Brazilian. I live here in US for the past 42 years of my life. Bolsonaro, what I wanted this Brazil, I forgot her name to let people know, it's how important it is the Bolsonaro's action on their great reform to the Brazilians and the Amazon forest, because that will help stop the burning and deforestation. Since you give land to people and you will know exactly who that part of land which is burning belongs to.

You can check it out if it is illegal fire, or it is a legal fire, because in Brazil, it is legal to burn the forest if you are the owner of the property. You can burn your property, a certain percentage for your crops or for whatever you want to do in your land. My question is, how important it is Bolsonaro's action and their reform [unintelligible 00:13:19] in the Amazon forest?

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, Marcus. You got the question, Manuela?

Manuela Andreoni: Yes, that's a very, very good question, because land tenure is, I believe, the most important issue driving Amazon deforestation. Land tenure in the Amazon is basically a mess. It's true. A lot of the region, no one knows what land belongs to whom and it is really important to sort that out. What Bolsonaro is proposing is not to settle who owns what, but rather to give amnesty to people who have grabbed land and deforested it illegally.

This has happened in the past a few times already. What he's proposing is just to extend the timeline for that amnesty. There are policies in place to try and identify who is doing the illegal deforestation already. The government did this self-declared registry of sorts where people can say where their farm is without actually having a title. The government already has this information, and there is no indication that it has acted on this policy that was implemented.

This registry, which is immense and thousands of people have contributed to it, and the government has only checked about what? 4% of them. I agree, I think all experts agree that land tenure is a major issue, but is what is being proposed? At least all the experts I've spoken to believe isn't going to solve this problem, it's just the same policy again, same policy that has been enacted before one more time.

Brian Lehrer: One more call, Pena in Greenpoint, you're on WNYC. Hello, Pena.

Pena: Hi, thank you for having me. I just wanted to say that when Bolsonaro mentions about the areas that are preserved, he's talking about the indigenous reserves, and the indigenous reserves are the areas where in the Amazon are protected and the indigenous people are really the ones that are actively trying to protect the Amazon basically at the moment. I was listening to your conversation with your guest and I didn't hear that mentioned.

I just wanted to say that there's almost like a genocide happening there now because of the conflict between the miners and the illegal loggers and the indigenous communities trying to prevent them from entering into their territories. There are daily conflicts and I just thought it was important to mention that.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for doing that, Pena. Anything to add to that, Manuela?

Manuela Andreoni: No, just that I agree that it's not 90% that is indigenous lands, much less than that, and actually one of Bolsonaro's promises when he was elected and one that he has followed was to not demarcate any more indigenous lands, which the constitution orders the government to do. She's right, indigenous lands are actually more preserved than the reserves that have the highest rate of protection, because there are people there protecting the forest so it doesn't get destroyed, but right now indigenous people are dying, they're being raped and tortured by people who want their land and who want what's under their land, gold and other minerals.

Brian Lehrer: Let's wrap up with the context of the presidential election campaign that's going on in Brazil right now. Also with the fact that in 2019, as I understand it, Europeans claimed that they wouldn't sign a free trade agreement with South America's trading bloc, Mercosur, until Bolsonaro reversed his environmental policies, and he hasn't done it and they still haven't signed it. That's an economic hit.

In the meantime, he has to defend these policies as he runs for reelection against former president Lula da Silva, and a few other candidates. I see da Silva is running as an environmentalist. What is he saying, or what are the other candidates running against Bolsonaro saying they would do most differently from him if elected?

Manuela Andreoni: Yes, basically the election looks like it's going to be between Lula and Bolsonaro because the other candidates are not doing well in the polls at all at this point. We haven't seen many specific proposals at this point, because the campaign hasn't started officially, but we have seen Lula try to shape his candidacy as a green candidacy, which we haven't ever seen before. Climate's going to play a role in this election that it has never played before.

What Lula's saying is basically that he wants to respect the law that Brazil already has in place. He says that he wants to protect indigenous lands. He actually promised this week that he would name a cabinet minister who would be indigenous, which would be a first for Brazil. These are the ways in which he's trying to frame his proposals. We haven't seen very specific things yet.

Brian Lehrer: That's our climate story of the week. Our guest has been Manuela Andreoni, writer for the New York Times climate forward newsletter and former Rainforest Investigations fellow at the Pulitzer center, joining us live from Brazil. Manuela, thank you so much for coming on. So informatively, we really appreciate it.

Manuela Andreoni: Thank you, Brian, for having me.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.