The Tulsa Massacre and the Case for Reparations

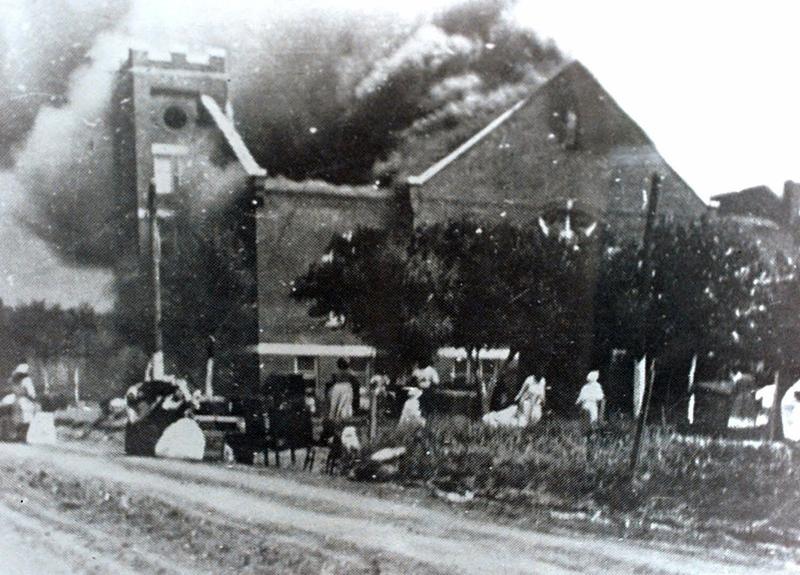

( Greenwood Cultural Center via Tulsa World / AP Images )

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. You've been hearing on this station about the 100th-anniversary commemorations of the Tulsa Oklahoma Race Massacre, in which historians say a coordinated attack on the so-called Black Wall Street neighborhood of Greenwood, in Tulsa, left as many as 300 Black people dead, 10,000 homeless, and 40 square blocks of the neighborhood destroyed. Those numbers, according to historians, cited in the Washington Post. We'll go over some of that history here too, but mostly in this segment, we'll ask this question about the present, after that kind of human rights atrocity, which included at least government complicity in its failure to stop the massacre, if not direct participation, what are the generational effects of all the wealth that was destroyed in that wealthy Black neighborhood? What does it add up to in dollars and cents, and what reparations are rightly owed?

There is both a bill in congress and a lawsuit seeking reparations on behalf of descendants of Tulsa massacre victims, as well as three actual survivors ages 101 to 107, who are still alive. Their names are Viola "Mother" Fletcher, Hughes "Uncle Red" Van Ellis, and Lessie "Mother Randle" Benningfield Randle. I guess when you get to 100 years old, everybody has a nickname. Justice for them, in the form of reparations, became an issue at this week's commemoration, as the Washington Post reports. The premiere event on Monday, a concert, organized by the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, was abruptly canceled over the question of reparations. The event called, Remember & Rise, was supposed to feature a performance by John Legend, and a keynote speech by voting rights activist, Stacey Abrams, but lawyers representing those last known massacre survivors said the celebrities pulled out after the commission failed to address requests that it use some of its funds to compensate them, the three 100-year-olds, for what they lost during the rampage.

In a minute, we'll talk to the Washington Post reporter who wrote that story, but also some of you have heard the first episode of a new WNYC podcast series with the History Channel, called, Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. It ends like this, does episode one, with our host, WNYC's, KalaLea.

KalaLea: For the descendants of the massacre of Greenwood, there has been no justice, no restitution. The people who were responsible have never been held accountable.

Right now, the city of Tulsa is confronting its past like never before. Public schools are finally including the massacre in their history curriculum. There's a new lawsuit calling for reparations. Archeologists have discovered mass graves that they believe contain bodies of massacre victims. What they find could answer the questions that have haunted the city for a century. What would it take to make it right to allow Tulsa to truly heal from this painful past? What would the city and our country look like if they succeed?

Brian Lehrer: What would it take to make it right, and what would the city of Tulsa and the county look like if they succeed? Check out, Blindspot: Tulsa Burning, wherever you get your podcasts, it's amazing. With us now are WNYC Blindspot host, KalaLea, and Washington Post correspondent, DeNeen Brown, who's been covering Tulsa developments.

DeNeen and KalaLea, good morning, and thanks so much for coming on.

KalaLea: Good morning, guys.

DeNeen Brown: Good morning. It's great to be here.

Brian Lehrer: KalaLea, we'll play a clip from the middle of the episode later, but we started with you ending there. No spoiler alert necessary in this case, because the story of Tulsa, the story of our country, is not over. What are some of the answers you're getting to the question you posed at the end there? What would it take to make it right, and what would the city of Tulsa and the country look like if they succeed?

KalaLea: Oh wow. That's a big question. I think, to put it simply, if you harm someone, then doing the right thing means apologizing, and rebuilding trust, and doing whatever it takes to make that person who was harmed feel good in their body. I think the descendants and the survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, have been just asking for repair, restitution, redress, and that can be in the form of, if you burn [beep] and destroy someone's home, then you should provide them with a home of equal or better value. I think, for me, just in reading about this and talking to many of the descendants, they just want, one, for the people to be held accountable, the people who either sat by and watched this happen or allowed it to happen, and also the actual perpetrators or descendants of those perpetrators who stole things; stole personal property, who destroyed their homes, for those people to be held accountable to an investigation to be enacted.

I think, one, the big thing, accountability, and two, for them to get their things back, their homes, their community. If you destroy a community, then you should be responsible for rebuilding that community.

Brian Lehrer: Before we bring in DeNeen, you also reference, in that clip that we played, that the people responsible for the massacre have never been held accountable. How did they get away with it? What does history tell us?

KalaLea: It's for me or for DeNeen?

Brian Lehrer: KalaLea, that's for you still.

KalaLea: I'm sorry. Okay, I'm sorry. Yes, well that's also the question of a lifetime here. One thing is that the Tulsa Massacre was not an isolated event. In the years leading up, and pretty much since the inception of this country, certain groups of people, mainly white people, have been able to get away with just about anything, murder, hatred, violence, harming other people, marginalize communities. I think that is the big question that I've been asking myself, since becoming a conscious human being, is why are certain people able to get away with harming and destroying other people's property, and that might be seen as a celebration?

If a sports league wins a game and they destroy their community or their neighborhood or stores or shops, why is that seen as a celebration or just a bit of rowdiness? Whereas if another group of people does the same thing, it's criminal behavior. I think, Tulsa Race Massacre, is very much like what we experienced in January 6th at the Capitol riots, at Capitol Hill, is if those people were Black and brown, we all know it, most of them would be dead or locked up by now. They wouldn't have gotten on planes, they wouldn't have been able to get on Amtraks and go back to their families. It would have been [beep] a lot more carnage and a lot more suffering. I think that's the big question we need to be asking ourselves. It's just skin. It's just melanin. Why are we behaving so differently towards certain people?

Brian Lehrer: It's tough to be a conscious person, right?

KalaLea: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Once you see things that are uncomfortable, you can't unsee them.

DeNeen, from the Washington Post, can you tell us more about how that premiere event on Monday came to be canceled? Who asked for what kinds of reparations from the commission organizing the commemoration, and what was their response?

DeNeen Brown: The plans for the Centinal Commissions, which is the city-sponsored commission that was organized or created to create events to commemorate the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, that commission has raised more than $30 million for the events and also for a museum called Greenwood Rising.

The lawyers who were representing these three survivors, as you mentioned, Viola Fletcher, who's 107, Lessie Randle, who's 106, and Viola Fletcher's little brother, Hughes Van Ellis, who's 100, the lawyers for those survivors sent in a list of seven requests. The requests included ensuring that the survivors receive some money while they're still alive, some direct support for the survivors who are living in abject poverty. They said that they did not request what the commission said it requested. Those negotiations broke down, between the Centennial Commission and the lawyers representing the survivors, that those negotiations broke down around Thursday, perhaps Wednesday of last week. The Centennial Commission announced on Thursday night that it could not proceed with this concert that was going to feature singer and songwriter John Legend, and also keynote speaker by Stacey Abrams out of Georgia.

I got word on Thursday night that the celebrities had pulled out after these negotiations broke down. That left a number of people in the city who were looking forward to see John Legend be dusted, but also the lawyers for the survivors say that they should be paid reparations. They should receive some money, as KalaLea said, for what they lost, and they're living in poverty while the Centennial Commission has raised millions of dollars. The lead attorney, who's filed a reparations lawsuit against the city and state officials, say that even as the Centennial Commission raised $30 million, not a dime has gone to these survivors, not one cent has gone to these survivors, who, as you said, are over 100 and living in poverty.

Brian Lehrer: It was a disappointment to people not to see John Legend and Stacey Abrams, but it made a lot of people look this issue in the eye if maybe they were able to look away from it before. DeNeen, what are the bill in Congress for Tulsa Massacre descendant reparations and the lawsuit, if you're familiar enough with either to describe them?

DeNeen Brown: This latest lawsuit was filed by survivors and descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre. It was filed in 2020, and it asks for repair, just as KalaLea said, it asked for repair for damages that were created by the massacre in 1921. It used the same legal reasoning as plaintiff fused when they filed a lawsuit against pharmaceutical company that caused harm with the opioid crises. It used the same legal argument there saying that those companies have caused damage in communities, and they won that lawsuit against the State of Oklahoma. The lawyers for the survivors use the same legal reasoning when they filed this lawsuit against the city, and State officials think that those entities are responsible for repairing the harm caused by the massacres to the survivors and descendants.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking about reparations and the Tulsa Massacre with DeNeen Brown, Washington Post correspondent, who's been covering the Tulsa Massacre 100th anniversary commemorations, as well as issues of reparations previously in her reporting, and KalaLea, who is the host of the new podcast from WNYC in conjunction with the history channel called Blindspot: Tulsa Burning.

Listeners, if you have any questions about the Tulsa Massacre, we know this is new and sanely, but new to so many Americans this year, you can ask it here. Maybe our guests can answer it for you based on their reporting. They're not historians, but they are journalists and producers steeped in this as of now. 646-435-7280. Maybe you have a family connection to the massacre. We would love to hear your family connections or any other connections. If you're a descendant of a survivor yourself or know anybody, how is this handed down or not handed down, 646-435-7280. Maybe you're even a white person who is a descendant of a perpetrator of the massacre. How do you come to grips with that in your family's past, and for anyone? How do we calculate as a nation? What is owed to descendants of the Tulsa Massacre? How do we calculate what is owed to descendants of enslaved people? 646-435-7280.

KalaLea, I want to play for people at one-minute stretch of the podcast that features a descendant of a Greenwood massacre survivor, who now gives tours, this descendant does, of the Greenwood area, named chief Egunwale Amusan. Listeners, you'll hear him talking to people on the tour, in this clip, interspersed with him talking about giving the tour. It starts with him on the tour saying what that Black Wall Street neighborhood was like.

Egunwale Amusan: You could go do any and everything within walking distance in the Greenwood district. Most people have no idea that the original cotton club was right here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The one in New York--

We started right in the core, in the heart of Greenwood. I show people what was, and what is no more.

Egunwale Amusan: This is the location of the Strafford Hotel. In 1918, this was declared the crown jewel of hotels in the United States of America owned by a Black man.

I take them to the places where bodies were dumped. I take them to the home of Wyatt Tate Brady, the city, founder, clansman.

Egunwale Amusan: He said, yes, I'm a member of the clan. I'm a proud member of the clan, so is my father a member the clan.

-so that they can see that he built a home that is the replica of Robert E. Lee. I take them to Standpipe Hill.

Egunwale Amusan: They occupied these Hills and fought for their lives.

The battleground location, where Black men fought to defend Greenwood. This explains why it was necessary to bomb Greenwood, because there was a losing battle on the ground.

Brian Lehrer: KalaLea, can you pick it up right from there? What did historians say was the nature of that battle on the ground, and what was that bombing from the sky that Amusan refers to?

KalaLea: Yes, it's an age-old story of an accusation that a young Black man named Dick Rowland, who was a 19-year old teenager, assaulted a young white woman named Sarah Paige in an elevator, and that's essentially a lot of rumors spread. The Tulsa Tribune, which is a white-owned newspaper, put out an article to say that Black man, that Negro who assaulted a girl in an elevator, and people were outraged as they were, especially in that time, a lot of white people, crowds of them came to a courthouse. There was a struggle and a fight ensued, and a gun went off. Somebody shot somebody else, and just everything erupted from there pretty much.

The next 16 to 18 hours, and Tulsa, starting in downtown Tulsa with those same groups of people, basically looting downtown Tulsa for ammunition, taking their valuables, taking guns and weapons, and then moving across the tracks into Greenwood. Then at 5:00 AM, a very coordinated attack, and that's when you hear about the bombing were allegedly, it appears as such because there's enough eyewitness accounts of this. Airplanes that were dispatched, were dropping turpentine bombs and incendiary bombs from the sky onto the roofs of these homes and thousands of businesses.

Brian, I think what I really want people to understand is, if you just look on your own block and think about the block in which you live, we're talking about 35 to 40-block radius here. This is not just one block of homes burned with businesses on your home, just think about that, 35 of these. It's a really large community, and it was almost like, I say this, and I know it's cliché, but it really does look like it was a war zone when you look at the pictures after. The level of destruction, the callousness that happened after the massacre, is also quite upsetting from people not being able to hold funerals or bury their dead.

I just read a story. I read one story a day about somebody who survived the massacre, just to start off my morning, and the story I read today is about a family who owned a store on Elgin Street, and their home was totally destroyed. She writes about her German Shepherd dog who also was burned in the fire. It was probably one of the first stories that I had read about someone's pet being harmed or being killed.

I think we have to think about this, you're talking about smoke, the smell of burning flesh, the smell of, it was a war zone. It was really an awful place. That battle, though thing that made Tulsa really different, and I'm 99% sure of this, is that there was no lynchings of a Black man in Tulsa, up to that point. The Black veterans who had just returned from the war, were determined to keep it that way. They went down to the courthouse to defend it rolling. That's where the fight ensued, because you had these men who just got home from war, they were treated very differently in France and other parts of the country, in the world, and they came back and they had a certain sense of dignity and pride about themselves, and they were determined to fight back. This is a story about destruction, but also a story about resistance, Black resistance.

Brian Lehrer: When we continue in a minute, listeners, we're going to hear a further description of the events of 100 years ago in Tulsa as spoken yesterday by President Biden, and he's the first president to go to Tulsa as President and do something like that. Then we'll continue with DeNeen Brown from The Washington Post and KalaLea, host of our new podcast with the History Channel, Blindspot: Tulsa Burning, and some of your many calls that are coming in now with some of your personal history. Stay with us.

Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we talk about issues raised by the Tulsa massacre. 100th-anniversary commemoration with KalaLea, host of the new WNYC History Channel podcast, Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. Listeners, I know we played a spot for that podcast in that break. That was just the luck of the draw that happened to come up. This whole thing isn't a promo for the podcast. DeNeen Brown, Washington Post correspondent who's been covering the commemoration, and she's also a University of Maryland journalism professor.

Here's a further description of the events of 100 years ago as spoken yesterday by President Biden, the first sitting president to ever visit Tulsa and acknowledge the history.

President Biden: A mob tied a Black man by the waist, to the back of their truck, with his headbanging along the pavement as they drove off. A murdered Black family draped over the fence of their home, outside, and only a couple knelt by their bed praying to God with their heart and their soul when they were shot in the back of their heads. Private planes, private planes, dropping explosives. The first and only domestic aerial assault of its kind, on an American city, here in Tulsa.

Brian Lehrer: President Biden yesterday in Tulsa. KalaLea, elsewhere in this speech, Biden said something that you also bring up in the podcast, that it wasn't a riot, it was a massacre. Why is that distinction important?

KalaLea: Well, a riot, as I say in the podcast, with the note that it was mutuality or a mutual event, and that was random. A riot breaks out, I'm mad at you, you're mad at me, we go head to head, we're on equal playing field. A massacre involves airplanes. It means that the fire department decides or is threatened not to put out the flames of your home. It also means that the sheriff and the police department seem not to be available, a 5:00 AM signal that rings out where thousands and thousands of white people start running towards your community at a certain time of the day at five o'clock in the morning. That was planned. That sounds like a plan to me, and it reads as such.

I think the word riot back then was used because the red summer of 1919 and even years leading up to the red summer, insurance companies would not payout policies if it was for a riot, if there was a riot that occurred there. I think it was, for an economic side of things, that's why they use the word riot, so that many insurance companies were not obligated to pay out policies, and that was written and that has not happened. There's thousands, there was so many people who tried to get their policies paid, and because of that Riot clause, that did not happen.

The word Riot is apropos-- I mean, excuse me, the word massacre is apropos because that's exactly what it was. When you go and harm people who are helpless and defenseless, like president Biden said, kneeling down on your knees to pray and being shot in the head, that's a massacre. Killing somebody's animals, that's a massacre. Shooting people as they run out of their burning homes, that's a massacre. It's undeniable at this point. We have enough evidence to proven it to be that way.

Brian Lehrer: Dwayne in Brooklyn is calling in with a reparations thought. Dwayne, you're on WNYC, thank you so much for calling.

Dwayne: Hey, how you doing? I don't think it's possible to compensate for all of that loss. It's not. We're a great country, and we've done great things, and just to make a small amend, something actual, not talk, will make such a huge difference. So many African Americans, that's what they're looking for, something to say, "Hey, we understand. We're going not just to just talk, action." America does action, and we can do action on this. Biden spoke the words and we could put this stuff into play. You can't make up for that stuff, but we definitely can make some amends towards African American people. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, Dwayne, please call us again. DeNeen, you want to put that call into context? It's so hard to know what to ask for, and Dwayne has one take on it.

DeNeen Brown: Well, I'd like to answer that by talking about what the Tulsa race riot report issued in 2001. Many of the listeners may know that in 1997, the State of Oklahoma created the commission called the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, and it was charged with investigating what happened in 1921 here in Tulsa, which is where I am now. They investigated, they collected stories from survivors, as KalaLea was saying, eyewitness accounts. They also collected information about what was lost during that massacre. Millions of dollars of property owned by Black people were lost in those burning fires. In 1921, when the white mob descended on Greenwood shooting Black people indiscriminately and setting fire to their houses. They shot black people as they slept in their houses. As was said before, they dropped turpentine bombs on the houses.

The Tulsa race riot report recommended that the city and the state pay reparations to repair for the losses that the Black people in Greenwood experience. People must know that Greenwood was one of the most prosperous communities in the country, not just Black communities in the country, the most prosperous communities in the country. It was called Black Wall Street. Actually, it was called Negro Wall Street by Booker T. Washington. It had a population of 10,000 people, it had luxury shops, it had 21 restaurants, 30 grocery stores, Black-owned hospital, a savings and loan, a post office, three really magnificent hotels built by some Black millionaires.

There were Black people with oil wells who lived here. They had jewelry and clothing shops. They had their own library, a bus and taxi service, and six private airplanes. The Tulsa Race Right Commission said, "It happened. There was murder, false imprisonment, forced labor." Forced labor is slavery. There was a cover-up and local precedents for restitution, meaning that they take some of the white people who own the ammunition and gunshots from which white people took guns to shoot Black people. White owners of those stores were paid back, but none of the claims filed by any of the Black people were paid.

The Race Riot Commission said that the estimated damage in 1921 was worth more than $1.5 million, and that the Black community filed more than $4 million in claims. None of those claims were paid. None of those claims were paid. You talk to some of the survivors, Regina Goodwin, a state representative here who talked about her great grandmother going down to the courthouse two days after the massacre, just filed for a claim, which was never paid. The commission said that the city did approve two claims succeeding $5,000 through guns and ammunition taken during the racial disturbance, again, that was paid to white people. It also said that this happened, that the white mob torched the very soul of the city. Also, the city tried to prevent Black people from rebuilding by implementing really restrictive building codes after the massacre.

You asked me earlier what's happening on Tulsa, but the feeling here is, among those who are defendants and survivors, is that reparations is long past due. It's long past due for the survivors and the descendants. The wealth that was lost in this massacre has extended through generations. We now have Black people in North Tulsa who are living, many are living in poverty, there's economic disparity. The life expectancy rate is 11 to 14 years lower than white people. 33.5% of Black people live in poverty compared to 13.4% in other parts of Tulsa. That's the case for reparations [unintelligible 00:31:48]

Brian Lehrer: I hear. For people who consider reparations an exotic notion, the Japanese interment victims in this country were paid reparations. I personally know a Jewish family here in the US, friends of mine, whose forbears on the bank in Germany, but had to flee the Nazis, leaving the bank behind. Eventually, Germany paid these descendants cash reparations because of their families' losses. These kinds of payments do get made.

DeNeen, I wonder if--

DeNeen Brown: One of the--

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

DeNeen Brown: Go ahead.

Brian Lehrer: No, just go.

DeNeen Brown: I was just going to say, the survivors and descendants were listening very closely to President Biden's speech yesterday. They were waiting for him to say the word reparations. Many left disappointed that he had not mentioned that word in particular.

Brian Lehrer: I was just going to bring that up. That's exactly what I was going to ask you, because it was good that a sitting president finally went to Tulsa and acknowledged this while in office. It was very different from, say, president Trump, who went to Tulsa last June to hold a campaign rally. He went to Tulsa last June to hold a campaign rally. He didn't even mention the massacre. Then he took credit for people knowing about Juneteenth. Oh my God. Yet Biden left some people wanting because he did not mention reparations.

As a Washington Post correspondent, do you happen to know if there were deliberations about that among the president and his speechwriters or anyone?

DeNeen Brown: That, I do not know. I do not know, but I know that he's gone on record saying that he is in favor of the HR 40 Bill, that actually got out of the judiciary committee, which is a historic achievement. I know that he has gone on record saying he's in favor of studying reparations, and that's what the HR 40 Bill calls for.

Brian Lehrer: Well, it's always studying. When you appoint a commission to look into things, it kicks the can down the road. Sometimes it's a way of saying no, that sounds like you're saying yes.

Matt in the West Village who grew up in Oklahoma. Matt, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Matt: Well, I was going to talk about the history, but we'll go a little bit into reparations because I am a CFO and I studied economics, and I lived in Tulsa. I've walked on those very grounds that we're speaking of. There's usually two problems in reparations, and this was a recent, such a whitening word right now and Biden, he'll say it eventually. Tulsa could be the model, because normally, first of all, establishing ownership or property at the time of anything that happens is often difficult. Those records don't exist. Secondly, valuation is also a problem. People might not know this, but the Oklahoma State University, and unfortunately, the Martin Luther King expressway, are built over parts of Greenwood that were taken by eminent domain. They paid valuation to somebody for that. Even though that's a low valuation, that's at least a starting point to get up to the proper valuation, which is many times higher. You can look at the discounted investments that you would get overtime and all that stuff and come up with a number. I could do it myself.

Secondly, when I grew up, and I remember this because people on Facebook had said, I never got this in Oklahoma history. I said it was at a reddish-orange book-- a reddish-brown book called Oklahoma History. You had it in the ninth grade, no one remembered this. I said, no, it's in there. It's a paragraph. It's very benign though. It's like a bunch of people got upset, and there was a race riot, basically. Very little detail. I told my friend this, and he pulled the book off the shelf, his mom was a teacher, and he read me the paragraph, and I was right.

Brian Lehrer: Do you have it?

Matt: The fatalities is about 30, but it was extremely denied.

Brian Lehrer: One paragraph.

Matt: It was a paragraph or two. I remembered a paragraph. This is a 1972. It's hard for me to remember exactly, but it was two paragraphs. I got interested in '97 when they did the, I think it was about '97, when they did the commission on it, and I started looking at the [unintelligible 00:36:21]. You had the internet. I'm looking and all of a sudden, I'm seeing these planes dropping bombs and machine guns. I'm thinking, oh my God, I didn't know anything. I've gone back to that area, and they've actually given white people money to invest in that area as part of revitalizing downtown. I don't think very many Black businesses all got hit on the gravy train.

I'll stay on the line in case you have any questions. I just wanted to say, thank God to NPR and PBS, because that's the only reason anyone knows anything about this. Thank you very much.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. I'm sure it's not the only reason now a lot of people are talking about it, but, Matt, coming from there and with that personal history and as a CFO invited you two journalists to ask him questions. Do you have any question for him? You don't have to, we can move on, but since he said it.

KalaLea: No, I think he said publish. Go ahead.

DeNeen Brown: I was going to say that you grew up in Tulsa. Did you hear stories from white people who were descendants of the perpetrators?

Matt: Unfortunately, wasn't a perp. In fact, I'm of German heritage. My first ancestors came right before the civil war. I had my fingers crossed. I pray to God he fought for the union. I pray to God he fought for the union. Thank God he fought. He was in Missouri. He fought for the union. You might be wondering, well, I can find them for you.

Brian Lehrer: No, but nobody you knew. KalaLea, did you have something or no?

KalaLea: No. I was saying, I would love for if he would publish. He said he could do the calculations based on the MLK highway that runs through Greenwood now. I'm wondering if he's published those if he's planning to do that.

Brian Lehrer: Then we could do that for the Cross-Bronx expressway, running through the South Bronx.

KalaLea: He could do it all over the country, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Matt, do that and call us back if you're willing, any day. We will put you on the air. Thank you so much for that.

One more before we ran out of time. Janine in Northern Virginia, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Janine: Hey, Brian. I've been doing some entertainment journalism, and I was able to interview for Black [unintelligible 00:38:53] and online publication, Stanley Nelson and Marco Williams, the directors of the film. Also this year, I was able to interview Michelle [unintelligible 00:39:02], the writer of [unintelligible 00:39:04] She's [unintelligible 00:39:05] great-great-granddaughter, who was documenting. She became a journalist because of [unintelligible 00:39:11].

Then I interviewed the filmmaker who did the lynching of Anthony Crawford in Abbyville South Carolina, who was an African-American man who basically was self-sustaining a town in South Carolina at the same time period.

He spoke up about pricing when he took his stuff-- He was supporting his whole community, and they made more money than the white community, and they lynched him, and they actually took all of his land, and they get his relatives out of town. There were hundreds of Black people in Abbyville South Carolina whose land was stolen.

There are thousands of stories of white folks taking the wealth of Black folks during the reconstruction era and into the early 20th century. I appreciate these journalists as you are down there. When I spoke to Stanley Nelson and Marco, I asked them how you process the trauma of having to watch this footage. I also asked the other filmmaker, how do you process the trauma as Black people, as storytellers, and [unintelligible 00:40:30], he said, "Well, you have to ask my wife. I don't know. I just keep working." Marco was like, "I just have to keep telling the story because I'm up to my neck. It's virtually killing me. I just did an interview with a current Black woman whose son was shot in Philadelphia. She became a politician. Her first son was shot in 2016. Her second son was shot in [unintelligible 00:40:56], just this year."

This is continuing. As we are telling these stories, we are traumatized, this country continues. Even the gentleman that spoke before, how he spoke was traumatizing because white folks can't even speak about how much of their wealth that has been taken. This country has been built on the blood, literally, and the bones of Black people.

This is the last thing I want to say, Martin Luther King's I have dream speech, this is the [unintelligible 00:41:32] He said, instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds. We refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds, and all the great opportunity of this nation. We have come to cash this check. A check that will come, that will give upon us to the advance of riches and freedom and the security of justice.

We need to elevate that part of the, I have the dream speech, and we need to continue the reparations [unintelligible 00:42:06] like student loan, debt, absolution for Black people, is what I would say.

That's all y'all. I thank you ladies for your wisdom, and the podcast is brilliant. I thank you, Brian, for elevating the story.

Brian Lehrer: Janine, thank you so much. Keep calling us.

Janine: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Wow. KalaLea, will you just wrap it up by telling people what's coming up on the podcast series? WNYC's, Blind Spot: Tulsa Burning . This is a six-part series that we're doing with the history channel that you're hosting, and it's only episode one that dropped yesterday. You want to just give yourself a little promo on the way out the door?

KalaLea: Sure. We have a lot happening. Like I said, this was not an isolated event. We're going to go a little bit into the history, a bit about after what happened during the war, the Great War, the World War 1. Then we'll touch on that there were two wars being had, one here in the US, and another overseas.

We'll touch on that and a little bit about Black resistance, which I mentioned earlier. What I'm really, really excited to share is that I am going to be speaking with a trauma therapist who deals with racialized trauma because, as I think Janine just questioned, this has been very hard. This has been probably the toughest project or story I've worked on.

I cry a lot, and I think it's really important for all of us to work through this trauma so that these things are not repeated. It was really important for me to talk to somebody that does this work. I'm really excited for you, Brian, and for everyone to listen to that interview.

Brian Lehrer: I can't wait. People talk about—

DeNeen Brown: Could I also—

Brian Lehrer: DeNeen, go ahead. Real quick, but go ahead.

DeNeen Brown: Sorry. I just wanted to tell the listeners that it's great to be here. I wanted to tell the listeners that I've worked on two documentaries regarding Tulsa. One is on PBS. It premiered on May 31st. It's called Tulsa, the fire and the forgotten, and the other is going to be on not National Geographic TV. It's called Rise Again: Tulsa and Red Summer. It premiers June 18th on Nat Geo TV and also on Hulu. That documentary also covers the red summer that set the stage for the 1921 Tulsa race massacre.

Brian Lehrer: I'm sorry, I didn't know about those pieces and mentioned them myself. Thank you for letting our listeners know about them.

DeNeen, KalaLea, thank you both so much.

KalaLea: Thank you, Brian. Thank you, DeNeen.

DeNeen Brown: Thank you. It's great to be here. Bye-bye.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.