Trump Said He Went to Coronavirus "School." What Would You Teach Him About COVID-19?

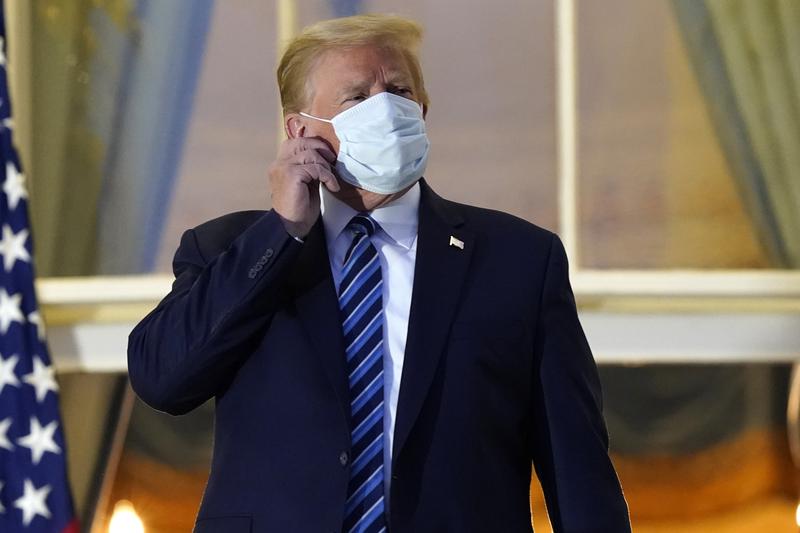

( Alex Brandon/AP )

[music]

President Donald Trump: It's been a very interesting journey. I learned a lot about COVID. I learned it by really going to school. This is the real school. This isn't the "let's read the book" school.

Brian Lehrer: That was President Trump from the video he made the other day from the Walter Reed hospital. He says he finally understands coronavirus now, and that having it was like going to school, as you heard there. We want to continue his education with a call in now for those of you who have also had the coronavirus or cared for a loved one who had the virus. What did you learn in coronavirus school? What do you want the president to understand from your experience, if it differs from his? 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. Like everyone agrees, the president should get the best medical care available, but why shouldn't everyone?

Let's go to school on this with the president. Medical care is supposed to be right, not a perk. President Trump went to the hospital the first day he was experiencing symptoms. He arrived in left by helicopter and he received multiple coronavirus tests, oxygen steroids, the antiviral drug remdesivir and an experimental antibody treatment. Okay. We'll give him the helicopter, but what kind of care did you or your loved one receive on day one? What kind of care was offered on day two? 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280.

Were you able to get a hospital bed right away, or even a test? If you got the virus back in March or April, let's say, but it's not fair to look at everything through the lens of March or April. Has it gotten better recently? It's true that the whole medical profession has been in coronavirus school for these past months. What treatments were provided if you or someone you know had the virus recently? 646-435-7280.

How much did your treatment cost out of pocket? The New York Times estimates that for someone who isn't president, Trump's treatment would cost $100,000 or so in the American health system. How much did COVID cost your family, even with insurance? We know there can be surprised billing and things that are uncovered. 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. Were you able to get your family member in the hospital, or receive other visitors? Remember when Donald Trump got bored during his stay at the hospital, he drove through crowds of his supporters. His closest advisors stayed with him through the day. Were you able to have access to your loved ones?

Did you have employees and PPE hazmat suits, take you for a ride outside? We know many of you couldn't visit your parents even as they were dying with this disease. Did anyone offer the drive-by limo option? How do you feel now if you're virus-free? President Trump says he now feels 20 years younger. We played that clip yesterday. He actually says he feels 20 years younger than before he got the virus.

Are you experiencing a new fountain of youth as well thanks to your coronavirus, or maybe the steroids, headaches, fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations. Those are more commonly the long-term effects that some people experience, but maybe the coronavirus was like the fountain of youth for you too. We want to know. The president says he got an education and what it's like to have coronavirus in America.

Let's continue his education right now with your experiences. 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. With us to help take your calls and answer some of your questions and mine is Dr. Craig Spencer, New York City Emergency Medicine Physician and Director of Global Health in Emergency Medicine at Columbia University's Irving Medical Center. You might know him as the Ebola doctor who survived that disease after treating people in Africa, where he went from New York and he was in the news for that at the time. Hi, Dr. Spencer, welcome back to WNYC.

Dr. Craig Spencer: Good morning. Thanks for having me on, Brian.

Brian: It's calls are coming in. Let's start here both from desivir and dexamethasone the steroid. Remdesivir is the antiviral. As I understand it, they're usually only given to patients who are severely ill with COVID-19 and often later in the course of their illnesses. Do you think this was the case of the president being sicker than the American people were led to believe, or that the real state of the art care that we all should have access to was exactly this?

Dr. Spencer: I think that's a great question. To just start with, I think that healthcare is a human right, and everyone should have access to high-quality healthcare, regardless of whether you stock produce at the grocery store or you're the president of the United States. Before I get into that, I want to reflect on you mentioning that the president received special care at different medications and perhaps many other people would have received if they went to the hospital, not only in March but even today.

We've known, since day one, that COVID treatment and really COVID itself is all about privilege. The president saying that he got an education on this is, I guess, akin to being admitted to Harvard Medical School when you graduate kindergarten, maybe it's an education, but it's definitely not the same as the experience that so many, really every other person has had, in dealing with COVID over the past eight months. Now, specifically on those questions, you're right.

I don't really know. We're all speculating on what the actual state of the president's health-wise. We got a little bit of an overly rosy description from his physicians. It was clear that some information was either being misheld and had to be corrected the day after. You're right. The medications that he was given remdesivir and dexamethasone are primarily reserved for severe cases of COVID. Did he have a severe case? It's really hard to say. Was he treated with extra things because he's the president of the United States? I think that's quite probable, but again, a lot of this is just speculation.

Brian: Yes. I've actually noticed what looks to me like a contradiction in some of the criticism by the media of the president's treatment and how it's being handled. I tend to lean in the other direction of this with what I'm most interested in, and what I mean by that is if he was getting remdesivir and dexamethasone, people were saying, "Aha, he's sicker than they're telling us."

Dr. Spencer: Right.

Brian: That might be true, but the other question that I think it's at least as important to ask was, if on the first few days after your coronavirus diagnosis, the best practice for the people we're supposed to care the most about, like the president of the United States, is to give them remdesivir and dexamethasone and the antibody treatment, then should we do that for everybody?

Dr. Spencer: That's a good question, because that is not the best practice. There have been maybe no other people other than the president who has received the Regeneron monoclonal antibodies, remdesivir and dexamethasone. We know that because there's only one press release, not even a publication giving data on the 275 people that have received the Regeneron monoclonal antibody.

We know that only 10 people have been given the Regeneron monoclonal antibody on a compassionate use basis. That's coming from the company. This is not an FDA-approved medication. It doesn't even have an Emergency Use Authorization. It has no approval. Basically, you have to ask the company to use this medicine. It's generally reserved for really sick people. There's generally a longer turnaround than just a couple hours. A lot of this goes into the problem. We just actually don't know the timeline of the president's illness.

It's possible he was sick or longer than they've let on, and that those medications, in addition to if his vital signs were worse than they presented, it may have been quite appropriate for him to receive these medications. Again, we just don't know, it's a bit of speculation, but you're right. There may have been no other people in the world who have received this combination of medications. This is definitely not the standard of care that you or I or anyone else would receive if we went to the hospital today.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Here's Debra in Keyport, New Jersey. Hi, Debra. You're on WNYC.

Debra: Hi, Brian. How are you?

Brian: Good. How are you?

Debra: I'm feeling well, maybe frustrated, but well. Yes, I'm calling like it's frustrating to see a level of care the president is getting over this when I suffered for so long without basically any care. I had to be my own advocate for my care. My doctor, my primary care doctor didn't know what to do with me throughout. I never struggled enough to have to go to the hospital, but I drove at least three times to the parking lot of the hospital and sat there and wondered whether I should go in and wished that I could have gotten the help. That was back in March. I tested positive three times before testing negative over the period of three months. I still suffered for months after. I still have odd, little symptoms. I've donated plasma four times. After seven months I still have antibodies and will continue to donate, but I couldn't get any help. I'm still not getting any help. I've had doctors tell me to just continue taking walks with the dogs. I don't know. I've followed up with cardiologists, pulmonologists, osteopaths, all for these different--

Brian: The president is using an osteopath primarily. We did a segment last week, if it makes you feel any better, to know there's a lot of company of people who are long-haulers, as the phrase goes, people who have continued to have symptoms.

There are so many people in your situation, Debra, you probably already know this, who are having symptoms that their doctors can't identify, or can't identify where they come from, or how to treat them, but that they didn't have before they got COVID and then ostensibly got over COVID.

Debra, I want to go back to the piece of the story that you told about when you went to the hospital. Did you say three times and sat in the parking lot deciding whether you should go into the emergency room? What was that like and why didn't you have a doctor who could advise you whether you should go into the emergency room?

Debra: Earlier on, back in March, nobody knew what to do about these things. Doctors offices weren't open for a few weeks. You couldn't get in to see your primary doctor because they were-- My primary doctor was only doing testing at that time. Driving to the parking lot and sitting there and calling my sister who's a nurse and she was telling me, "You could go in there and you could possibly infect people, and they're probably going to turn you away because you can breath."

I wanted to go in because I was having these-- It wasn't just my breathing that was bothering me. My heart was out of control. I had pains in the back of my head. I wanted some information from somebody, but I was afraid to go into the hospital for numerous reasons, A, to be turned around, B, to get somebody else sick, or what if I don't come out.

Brian: Continue as a last thought before you go. President Trump's coronavirus education, is there any particular thing from your experience or just your observation since then that you'd like him to know?

Debra: I'd like him to consider that there are so many people that have had different experiences with this, different symptoms, different long-lasting symptoms, and we don't have the level of care. We don't have expert doctors all around us. Most of the doctors that I've spoken to really just scratch their heads, and it's not for-- It's because they're not getting any information from anybody. The information that they're getting is being contradicted every day.

Brian: Thank you so much for your call. I hope you continue to improve and I hope the lingering symptoms resolve. Thank you, Debra, for your openness. Dr. Spencer, what are you thinking?

Dr. Spencer: I just want to thank Debra for sharing her story. Listening to that, the thing that stuck out the most was not how sick she was and how many times she tried going to the hospital, we heard that so often, but the fact that she was actually able to even get tested. If you remember, in March and even throughout April, it was so hard for people to get tested.

Again, this was at the exact same time that Tom Hanks was getting a test, and entire NBA teams were being tested when we were sending people away from the emergency department like Debra without testing them. Again, COVID has been about privilege since day one.

It continues to be about privilege as we're hearing about precautionary hospitalizations for people that quite frankly flouted public health principles are now checking themselves into a hospital when people like Debra were afraid to go to the hospital. This just isn't right. I also want to say to Debra, there is a lot of information that's emerging on the long-haulers. I've shared a piece a couple of weeks ago on the Washington Post, looking at all the research. I'm a long-hauler myself from a different viral illness. This is real.

You are in company that understands this as being much more widely understood right now. There's more research. There'll be more appreciation. I know now in the UK there are NHS public clinics for long-haulers. I think we're going to be hopefully seeing more of that in the future here as well.

Brian: It's like people with chronic fatigue syndrome have been saying this for years, "I'm feeling all these symptoms, and doctors can't find any reason for it and they think it's in your head."

Dr. Spencer: Right. I hear that all of the time from long COVID or long-hauler patients who've been told this is all anxiety. I bet you there's a big component that's anxiety because you're feeling sick. You have problems that are documented. We know the impact of COVID long-term can be neurologic. It can be cardiac in the heart. It can be in the lungs. It can be in the kidneys. If you keep going to a medical professional with real medical issues and they keep telling you it's anxiety, that's going to make you anxious. That's going to make you upset. That may make you depressed.

Brian: Andy in the Philadelphia area, you're on WNYC. Andy, thank you for calling in.

Andy: Yes, hello. How are you today?

Brian: Good.

Andy: Thanks for taking my call. My experience was slightly different, of course. My daughter contracted the disease, didn't even know she had it. She had a fever, had a sore throat. We assumed or we suspected that she had strep-throat which had been going around, but we hadn't tested for COVID which was not hard at all. This was over six weeks ago, went to [unintelligible 00:16:32], got it done immediately, had a quick turnaround.

There were all types of people getting tested at the time, so the access wasn't really an issue. She did have it and she quarantined in the home. I had it earlier, but not the same time frame. I had other specific issues other than a little bit of a cough and a fever and recovered well from that as well and didn't require any real intervention. I'm on immunocompromised medication or immunosuppressant medication as well for an autoimmune disorder. I'm 68.

The presentation can be very variable and unfortunately that's varying from different age groups. Of course, if you're somebody like the president, they're going to do whatever they can above and beyond what you would normally expect, I believe, needed to be done on a regular basis simply because he is president and his position warrants that. It's like, I don't have three secret service guys following me around in an armored car. Unfortunately, I think that whole comparison is rather semantic, quite frankly.

Brian: I think it raises a real moral question. Do I understand from our screen that you're a doctor, you're a pulmonologist. Is that accurate?

Andy: Yes. Yes, it is.

Brian: How much special VIP treatment should the president of the United States get compared to anyone who walks into your office when it comes to something as basic as having the coronavirus?

Andy: Quite frankly, he's got, first of all, risk factors. You're going to treat somebody who has additional risk factors or comorbidities more aggressively, and that's usually the standard of care. Now remember, you understand that this has changed appreciably over the last six months. What was being done early on compared to what is being done now has changed appreciably due to the knowledge about the disease. Protocols [unintelligible 00:18:31] come out, and there's still additional protocols and things that are not there in the [unintelligible 00:18:35].

Brian: I want to focus on the moral question, doctor. Obviously, the knowledge base has evolved since March and April to now.

Andy: I don't think it's a moral issue. He's the president.

Brian: No, no, here's the moral question that I'm asking you and you can answer it however you want to answer it is, if somebody else who was his same age, with his same risk factors came to you and you thought a combination of polyclonal antibodies and remdesivir and steroids was the best thing you could do to protect that person's health, Joe or Jane Average who walks into your office as a pulmonologist, with the exact same risk factors as the president, why wouldn't you give them that treatment? Why wouldn't you say they deserve to have the same treatment if that's the most protective thing that medicine can offer?

Andy: First of all, if you're convinced that that's the case. First of all, as your emergency room physician mentioned that these protocols [unintelligible 00:19:40] new. There haven't been that many people that have been tested or have been in the study for this. They don't know the long-term risk factors. They don't know the efficacy of these either. What's happening here, I think, is basically, if the downside is minimal and the upside is a potential plus, they're going to take that chance simply because of who the person is and ramifications if that person succumbs or dies, country spirals out of control potentially, you don't know. It's a difficult choice, but the bottom line is, if these interventions are available, then you would [unintelligible 00:20:14] through those interventions, if you could actually get them. In the beginning of this, they weren't even available, or extremely difficult to get. You had to choose those. It's triage essentially, to some degree.

Brian: Andy, I'm going to leave it there. I really appreciate you calling in. Dr. Spencer, what were you thinking about during his explanation of that? Maybe there is a hierarchy of value here. It's the president of the United States, so you do this, you don't do it to everybody.

Dr. Spencer: Sure. I think that's a good point, Andy. Thanks for sharing that. This is an ethical question. I remember working in West Africa during Ebola, when we had a similar medication to the Regeneron antibodies called ZMab, and there were questions around whether or not we should be giving this to our colleagues, on the front lines in Africa, the Africans themselves that were working. Ultimately, it was decided that, no, we wouldn't because we didn't want to be seen as experimenting on people. However, when I was in the hospital in 2014, we got a call from the FDA that they'd be more than happy to send this medication to me.

It's an ethical question. I am not so upset with the president getting access to the best cutting edge treatment. I think it's true. It's a national security issue and we need him as well as everyone to be healthy and stay alive. What I'm concerned about is that the baseline is not as good. It's the fact that people don't have access to the baseline care that they need to be healthy.

People are going into an infection with COVID with a higher risk or a higher prevalence of comorbidities because of under-investments in public health, because of disparities that exist in the system. Those are the same disparities that prevent them from receiving the same medication from going into Andy or other people's office and getting access to the same level of care.

We've seen throughout New York City, we've seen throughout the country that the death rate from COVID is twice as high for Black patients and nearly twice as high for Native American, Alaska Natives. It is disproportionately impacted marginalized and vulnerable groups who have already been largely disproportionately marginalized and vulnerable from our public health and from our medical system. That's what my concern is. I'm less concerned with the access that the president has to specific information, to specific treatments, but I do want to make sure everyone should have access to the same care as anybody else. That just has not happened in March or even now.

Brian: Jennifer in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC. Hi, Jennifer.

Jennifer: Hello. How are you?

Brian: Okay.

Jennifer: I want to talk about my experience. I told the screener, I'm an African American woman who lives near Prospect Park, full-time caregiver of my mother who has dementia, and my brother was here, who is about 50, with diabetes. He started getting sick at the end of March and he was very ill fatigued, no cough, but he had a high fever. By the time I called the ambulance, he was quite sick.

They sent him to the local hospital at about six in the afternoon, in the evening. The EMT is telling me they're probably going to keep him because his blood sugar level was high. I got a call from him at 4:00 AM telling me that they're discharging him and without any transportation, nothing, I had to find a way to get him home. It's four in the morning. I luckily had Uber account. Luckily, this guy was willing to take him. He couldn't even walk to the cab. He's got there. He got home. He was still sick. They never gave him a COVID test. Nothing.

Luckily, I knew of an emergency room in Brooklyn that I take my mother to, that not too many people know of affiliated with NYU. The next day, I had to take him myself because the EMTs would not take him to that emergency room. I had to get my mother's wheelchair, wheel him, leave my mother. Luckily, I knew how to get an accessible, wheelchair accessible cab to take us downtown, to take him to that ER where they immediately gave him a test. There was no one in that-- That's the other thing, at this hospital near me. They left him in the hallway on the gurney for the entire time.

Brian: Jennifer, I don't know whether to cry or to shake with rage at your story. We're running out of time in the show. What do you want the president to know?

Jennifer: I want the president to know that everyone does not have the same level of care that he does. Thank God. My brother, I knew to get him to a hospital, a top level hospital where they took care of him. He stayed for 10 days. He had to be [unintelligible 00:25:14]. They immediately gave him a COVID test. If you don't have that level of access and don't have that level of knowledge of where the care is available, how you can get your loved one there, then it's not an easy road. It's not the flu. This is something that is deadly. It's many, many people.

Brian: Thank you so much. I'm sure that was not easy to share. Oh my God. We have one minute left, Dr. Spencer. I want to note that you retreated Donald Trump's tweet about you from 2014 this week. It said, "The Ebola doctor who just flew to New York from West Africa and went on the subway bowling and dining is a very selfish man, should have known." Why did you bring that up?

Dr. Spencer: Because I've seen over the past two days as the president received care that none of us would have, and then undermined really stories like those that we just heard, the impact that it had on communities, the impact that's had on 210,000 Americans and the impact that's had on all of the families I talked to at the height of this during the peak and held their family [unintelligible 00:26:31], they died.

It's so disheartening and so sad to recognize that the failure of our president to empathize with all of those stories we've heard here today, and all the stories we've heard over the past eight months, is, in fact, the greatest threat to the public health right now in the country, by undermining science, by undermining the public health response that we need. There will be more people that can sick from this and the more people that will die and there'll be more stories like those really horrific ones we just heard. That's why.

Brian: Dr. Craig Spencer is an Emergency Medicine physician and Director of Global Health and Emergency Medicine at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Thank you so much.

Dr. Spencer: Thank you, Brian.

Brian: Listeners, thanks so much for your calls.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.