Trump Indicted Again: What it Says About American Democracy

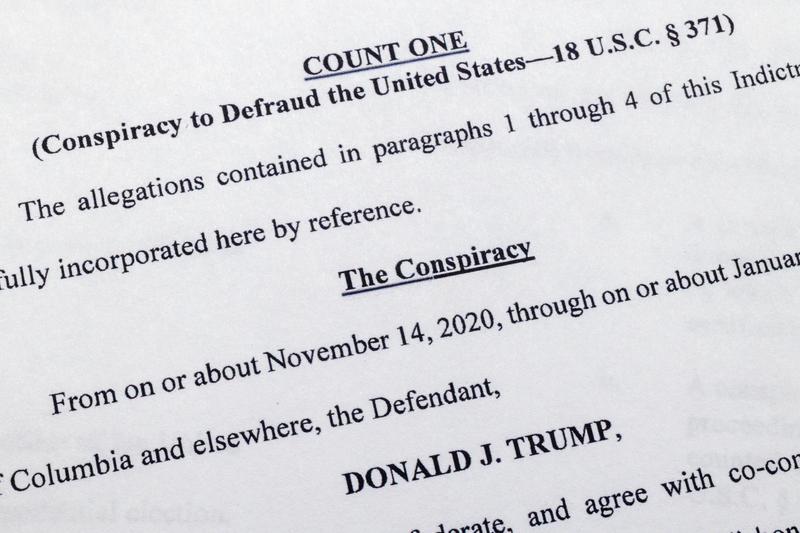

( Jon Elswick / AP Photo )

Speaker: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Well, let's keep trying to understand the January 6th, the big lie indictment of Donald Trump. We'll assume you know some of the basics by now, a 45-page indictment, four counts, six unindicted co-conspirators, widely believed to include Rudy Giuliani and others. The basic charges include three conspiracies.

To defraud the United States, to corruptly obstruct the January 6th proceedings in Congress, and perhaps most interestingly and most importantly, a conspiracy against the right to vote, and to have one's vote counted. With us now, NYU law professor Andrew Weissmann, former general counsel to the FBI, a lead investigator in the Donald Trump Russia investigation under Robert Mueller, and author of the book on that experience Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation, and he's an MSNBC legal analyst.

Andrew, I know you've been on the air so much over the last day, so we really appreciate you making some time for us again. Welcome back to WNYC.

Andrew Weissmann: Always great to be here, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: To start on the big picture, was this more or less the indictment of Trump you were expecting, or did Special Counsel Jack Smith surprise you in any big ways?

Andrew Weissmann: Just to sound like a lawyer, the answer to that is yes, in that it is the indictment that I think we all were expecting. It does follow very much the framework of the January 6th committee, and owes a huge debt to them, in terms of uncovering the facts. Obviously, there are some additional facts because they were able to get the testimony of the former vice president, and that's clearly reflected in the allegations.

I think the thing that surprised me a little bit was the very, very skillful use of certain crimes, and the way it's framed to avoid certain legal issues that I think may not be totally apparent to people, but for instance, they avoided, by not charging insurrection, they avoided claims of selective prosecution, both legal ones and rhetorical ones, by not going back to a charge that hasn't been brought in over 100 years.

They didn't focus as much on the former president's statements on the Ellipse, so they avoided 1st Amendment challenges, because this is not focusing on just a speech and inciting a mob based on that speech, so they avoided those claims.

Brian Lehrer: That speech on the Ellipse, on January 6th, where he was dispatching his supporters to go the Capitol.

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly. Then the other is, it's unusual to be so clear about the criminality of six co-conspirators. It's fairly easy to identify at least five of those people, from the very detailed allegations. If I were those people and their defense lawyers, it would be abundantly clear that they are going to be charged, if they haven't already been charged under seal, in connection with the allegations here, but I don't think they're going to be charged in the same indictment as Donald Trump.

This clearly, to me, indicated that Jack Smith wants to have the first trial with respect to Donald Trump, and that he's going to try and make sure this case goes to trial before the general election.

Brian Lehrer: Let me pick out one of those things you just referred to, and ask you to drill down on it a little bit. January 6th itself, one thing I was waiting to see was if they charged him with a criminal act of omission, and I didn't know what the charge would be, I'm not a lawyer, but watching the Capitol break in on TV, and doing nothing to stop the violence when people were repeatedly calling him that afternoon and asking him to please say something, because he had the power, with those people, to call it off.

They didn't explicitly charge him with that, but as I'm reading it, they did charge him with exploiting the riot. The indictment uses the word exploiting. Can you explain that charge?

Andrew Weissmann: Sure. They are using his sitting on his hands as evidence. It clearly is relevant to his intent at the time, but they very much focus on things he was actually doing. To me, it was quite powerful, because all of us lived through watching the events before our eyes on January 6th, and the idea that there wasn't horror on the part of any citizen, let alone the president of the United States, to see the Capitol being attacked, the vice president put in danger, the senators, congressmen, congresswomen, staff, law enforcement.

That the reaction was not just an omission, but actually continuing to overthrow the will of the people. They were continued acts going on, while that was occurring. To me, was chilling, in terms of him doing it. Then the question that you have about violence, I thought that that was a very skillful use in the indictment, where they say he took advantage of the violence that was happening to try to continue his effort to overthrow the will of the people, but they don't get into an issue of whether he incited it, and that piece of the case.

Again, they're avoiding 1st Amendment issues, but they're clearly putting the violence into the charged conduct here, so it'll be front and center before the jury.

Brian Lehrer: Can you explain how that might get front and center before the jury if they're charging him with taking advantage of the violence? Taking advantage how?

Andrew Weissmann: One of the things that is alleged is, if you look at the end of the allegations, he is talking to, and he has various co-conspirators continuing to talk to people in the Congress about needing to delay or prevent the electoral votes being counted, saying that given the attack and the violence, that it makes sense to put this off. It meant basically doing whatever he could at this point, since it's his last-ditch effort to avoid the joint session of Congress reconvening and deciding that he is not going to be the future president of the United States.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. If we remember the events of January 6th, they did actually suspend the certification of the electoral votes process while people were in danger, and were taking cover, et cetera, and they came back, I think, about six hours later. The indictment says Trump was actually using that suspension to ask senators to continue that suspension, to reconsider certifying the election at all. Why is that a crime? Why isn't that hardball politics?

Andrew, I could ask that about any number of the points in this indictment. Where the line is, between playing hardball politics and committing a criminal act?

Andrew Weissmann: Sure. I guess it depends what you mean by hardball politics. If hardball politics means lying to elect, let's say, state electors, to get them to change vote tallies, if it means getting the Department of Justice to issue a statement that the states should relent in terms of counting, or certifying votes, or reconsider that, because there was fraud in the election, when the DOJ, in fact, didn't find that there was fraud in the election.

If it's lying to your own vice president of the United States about what has occurred, what his powers are, lying to the American people about the vice president's position about whether he has the power to act, which the vice president had repeatedly told the president he doesn't have that power, but the president, on January 5th, issued a press statement saying that the vice president agreed that he does have that power.

One of the things that I actually find quite salient, because it was on January 5th, and the vice president is clear that he has consistently said he did not have that power, and he acted accordingly to his credit at the time.

Brian Lehrer: Let me jump in on that one. When is lying to the public, a politician lying to the public, a crime?

Andrew Weissmann: Just to be clear, the indictment goes out of its way to say, "If that's all you're doing, if all you're doing is lying to the American public and saying, "I won the election," that's fine. That's not a crime because you haven't taken action in furtherance of that. If you want to file a lawsuit challenging any particular state's election counting, assuming that the lawsuit is not frivolous, that's the appropriate means.

The indictment goes out of its way in the introduction to say, "Those are the lawful means," and then you abide by that legal process. That's what it means to be the rule of law. If you have an opportunity to present your evidence in court, they lost all of those cases, and that's the legal means. You don't get to take the law into your own hands. The issue is really not about hardball politics versus a crime.

The issue is that yes, there is free speech, but if you start acting on what you know is false to undermine the will of the people, that is a crime, and in this case, the allegations are proved this is the most serious crime that I can ever think having been charged, because it goes to the fundamental rule of law in this country, and what it means to be a democracy.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your first impressions of, and questions about the Trump January 6th, and big lie indictment, at 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Call us or text us at 212-433-9692. You can also tweet @BrianLehrer. We'll have three different guests on this today. Andrew Weissmann for another few minutes. Michael Waldman, from the Brennan Center for Justice. After that, then, we will do some other things on the show today.

We're not going to spend the full two hours on the indictment, but then we will come back to it later in the program, with Catherine Christian, former assistant DA in Manhattan, who's been on the show before, talking about these matters. We're going to do one, two, and then last in the show today, just to do some bookkeeping for you, on the Trump indictment, and we will do some other things in the middle.

Also, as a program note, we are now planning to read the full indictment, or as much of it as we can do in two hours, on the air, on Friday. Jack Smith has asked everybody in America to read the full indictment, and we're going to help you do that. We're going to do the audiobook version on Friday's show. I haven't figured out yet whether we can do it in two hours. If we can't, we'll do some edits to make it doable in our time, but that's something to look forward to for Friday.

I'm not going to read for two hours myself. I promise we'll get some other people to come on and share it with me, but we will read the full indictment, or as much of it as we can in two hours, on Friday, and we'll take your calls, your impressions, your questions in our three segments on it today. 212-433-WNYC. Right now, with NYU law professor Andrew Weissmann. Andrew, having read through it yourself, and I've printed it out, I'm holding the 45-page indictment in front of me. Any estimate? How long it would take to read it out loud?

Andrew Weissmann: It might be quite long. I think you can do it under two hours, and it is something that I would commend to people. It is really beautifully written. It's very clear, and if the allegations are true, it does suggest criminality not only on the part of the former president, but also is very, very clear, with respect to the six conspirators who are unnamed, but five of them are readily identifiable.

It just is not going to be surprising at all to me that they will find themselves charged, but I don't think they'll be charged in this indictment. I think they will be charged in a separate indictment. Also, I think does suggest that there may be a lot of state investigations into them, because this indictment does lay out both federal and potential state crimes that they committed.

Brian Lehrer: Can you clear something up for us? I'm hearing a four-count indictment, but I read from the indictment, in the intro, the three conspiracies that he's being charged with. Is it three charges, or is it four charges?

Andrew Weissmann: It's four charges. There are three conspiracy charges, and there's one obstruction and attempt to obstruct charge. What I'll call the 1512 obstruction, that's referenced to the statute 1512 of the code, that is charged both as a conspiracy and as an attempt. That's why there are four charges.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call. Here's Nelson, in Brooklyn. Nelson, you're on WNYC, with Andrew Weissmann. Hello.

Nelson: Thank you. My concern here is that he loses all the cases that are out now, and he just keeps appealing these things. At some point, he'll be 85 or 86 years old, because my feeling is that it's going to take five or six years after all the appeals. What judge in this country is going to put an 86-year-old ex-president in prison?

Andrew Weissmann: Nelson, that's a really good question. There are a lot of ifs there, but assuming that this case goes to trial, assuming that Donald Trump does not become the president and end the federal cases, assuming a Republican president other than Donald Trump doesn't become president, and the cases-- Assuming this case goes to trial, assuming there's a conviction, at that point, there are three, there may be four criminal cases. A judge does have the ability to send the person to jail even while an appeal is pending.

That happens quite often, that the person doesn't remain out and about while an appeal is pending, particularly if there are no significant legal issues with the trial. That's one possibility. The other is that having prosecuted a number of mob cases, where some of the defendants were quite elderly, those people still went to jail. Now, the crimes were very different, but I don't think that the age of the defendant, at least federally, under the United States sentencing guidelines, is supposed to be a factor that is considered.

Unless it is when the person is a minor, in which case, it really does go to their level of culpability. I actually took from this indictment, knowing the judge who was assigned, Judge Chutkan, who has handled so many January 6th cases, as have so many of the judges in the District of Columbia, that I think the prospect of Donald Trump, if he is convicted, going to jail, I think, rose dramatically, because of the rule of law and the fact that a leader of a conspiracy should not be treated any less harshly than the foot soldiers who have been sentenced to [unintelligible 00:19:00] jail time.

Brian Lehrer: Ah, and I think we have a call right on that point, that's wondering why he wasn't charged with some particular things. Rob, in the Bronx, you're on WNYC, with NYU law professor and former Mueller lead investigator, Andrew Weissmann. Hi, Rob.

Rob: Hi. I don't agree that Trump shouldn't be charged with sedition. People who took part in the riot and attacked the capitol have already been charged and convicted of sedition and their part in the attack on the capitol, and Trump egged on the mob. He's the one who organized the mob. He's the one who sent out invitations, as it were, to gather this mob, sent them there to attack the capitol, and refused to call them off.

We know this from the January 6th hearings in Congress. I don't understand why he hasn't been charged with sedition.

Brian Lehrer: When so many of the rank and file individuals, dozens and dozens of cases, people have been charged with, and as the caller says, convicted of seditious conspiracy and other things having to do with the actual break-in. It's a good question, Andrew.

Andrew Weissmann: That's an excellent question. Just so the record's clear. Many, many people have been charged with obstruction of Congress. That's the 1512 charge, and the former president is now charged with that as well. That fits very much with what has been charged routinely against many people. It is a far fewer number of people who've been charged with seditious conspiracy. That is not a routine charge.

The difference between obstruction and seditious conspiracy is that seditious conspiracy requires the government to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they intended the obstruction to be accomplished by the use of force. The government, I think, obviously decided that based on the evidence that they have, that they had concerns about being able to prove that element beyond a reasonable doubt.

Remember, the standard is beyond a reasonable doubt to a unanimous jury. The cases that have charged seditious conspiracy for instance, with respect to the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, there was very explicit evidence and text messages about the use of force about accomplishing the obstruction through that particular means. I really do understand the caller's concern. I think colloquially, we all can say that we are aware that the President understood, or even intended that there would be that use of force.

I think this likely came down to an issue of knowing what proof they had, whether they would be able to prove that element to that very high standard that's required under the criminal law.

Brian Lehrer: Do you think he gave himself cover against seditious conspiracy charges with that one line in the ellipse speech on January 6th, "Go patriotically and peacefully to the Capitol"? He put it something like that. Those may or may not be the exact words, but I think it was patriotically and peacefully. He threw in the word peacefully on that one occasion, after recruiting people with his will-be-wild invitation to come to Washington on January 6th, then December--

All of that stuff, all the implications that we have to go over there and take back our country, and all that other stuff. Did he cover himself legally by saying the word peacefully one time in that speech, and that's why he's not charged, but leaders of the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys are, with seditious conspiracy?

Andrew Weissmann: Well, I'm in violent agreement with you that the reason he, in my opinion, made that statement, included that word, was because he knew precisely where the line was, and what he could and could not say. This is a man who's been in many, many, many legal fights, and is very aware of things like libel laws and incitement, and where the lines are. I do think that's the reason that he said that, for the same reason that he will denigrate somebody and then throw the words like it's in my opinion.

Things that, again, it's so clear he just does that to give himself that plausible deniability. I don't think I would say that's the only reason, because I think the indictment was very skillful in not overplaying and relying too much on the ellipse and buying yourself a huge fight that would end up in the Supreme Court, about the 1st Amendment, and what is incitement and what is not incitement, and instead focused very much on actions, specific things that the president was trying to do with the specific schemes.

Whether it's at the state level, which is outlined chapter and verse. Whether it's with the Department of Justice, whether it's with the vice president, or whether it's with individual people in Congress. I think it was just very skillful that, as I mentioned, the outset that they were trying to avoid those legal fights, particularly understanding the makeup of the Supreme Court of the United States at this time.

Brian Lehrer: Before you go, and we bring in our next guest, Michael Waldman, from the Brennan Center for Justice, and continue on this, you wrote the book Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation. You were a lead investigator with Mueller. You were disappointed, I think it's fair to say, with how that investigation of Trump did end. Do you think Jack Smith learned any specific lessons from the Mueller investigation that you see applied in this indictment?

Andrew Weissmann: That's hard to say. I do think that the biggest thing that that he has going for him is that he's able to charge the former president, because he's a former president. That was nothing that we could actually do under Department of Justice Rules. I think other things that he has done is, he's kept a very low profile. He is speaking through his actions in court.

He's taking, I think, additional steps, that we did not take, to protect his people who are subject to he, and many other state law enforcement and judicial officers are subjected to incredible threats of violence. I think those are all steps that he has taken. I think the main thing he's doing is very similar, which is keeping his head down. I think he is like Robert Mueller. He is acting very, very quickly, and is aware of the clock, because of the position he was put in.

He has not been the special counsel for terribly long, and he has really done a remarkable job, in my estimation, in terms of speed, in getting these two indictments out, and as they're so so detailed. Now, obviously, he had a significant amount of work done by the January 6th committee, by people of the department, before he was appointed. It clearly shows an enormous amount of work in a short amount of time.

Brian Lehrer: NYU law Professor Andrew Weissmann, former general counsel to the FBI. A lead investigator in the Donald Trump Russia investigation under Robert Mueller and author of the book on that experience, Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation, and he's an MSNBC legal analyst. Andrew, thank you so much.

Andrew Weissmann: You're welcome.

Brian Lehrer: We'll change guests, but not topics, right after this. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer, on WNYC. Let's keep trying to understand the January 6th and big lie indictment of Donald Trump. We'll assume you know some of the basics by now. A 45-page indictment, four counts, six unindicted co-conspirators, widely believed to include Rudy Giuliani and others. The basic charges include three conspiracies to defraud the United States, to corruptly obstruct the January 6th proceedings in Congress, and perhaps most interestingly and most importantly, and we'll talk about that in some detail now, a conspiracy against the right to vote and to have one's vote counted.

With us now is Michael Waldman, president and CEO of the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School, a nonpartisan law and policy institute that works to revitalize the nation's systems of democracy and justice, as they described themselves. He was director of speech writing for President Bill Clinton from 1995 to 1999, and he's the author of a new book called The Super Majority: How the Supreme Court Divided America. Michael, it's always good to have you on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Michael Waldman: Great to be on.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we'll keep taking your first impressions of, and relevant questions about the Trump January 6th and big lie indictment, at 212-433-WNYC. Call, text, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Michael, you focus on democracy at the Brennan Center. Are you most interested in the charge here that's stated as conspiracy against the right to vote and to have one's vote counted?

Michael Waldman: I think that is an extremely important element here, and it was when the news came a few weeks ago that Trump had gotten a target letter. That was the new element, and I think it's very, very valuable for us to understand. This indictment is framed not just as a conspiracy to have the fake elector scheme, not just as a conspiracy to pressure the justice department to act, or to pressure Mike Pence to act, but a conspiracy against democracy and the constitution, and in particular, the ability of voters to choose the president.

You heard Jack Smith say that. It really, in that way, puts on trial, not just Trump or Trump's co-conspirators, alleged co-conspirators, but the big lie, the idea that there is widespread voter fraud and that we ought to be acting to respond to that. This didn't start with Donald Trump. It didn't finish on January 6th. It is still driving a lot of push for law changes all over the country, and it was pretty clear, at least in the indictment, that this is not just a claim or a notion, but a deliberate and conscious lie about our elections.

I think it's very important.

Brian Lehrer: Is that a civil rights charge? You had an article released by the Brennan Center that speculated there could be a civil rights charge against Trump here. When Jack Smith states it as a conspiracy against the right to vote and to have one's vote counted, and used the word, in that context, conspiracy against the right to vote, is that a civil rights charge? Would you call it that, in the way that you were speculating about a few weeks ago?

Michael Waldman: There are a variety of laws that are used to protect elections, and they're often used in the context of stopping racially motivated or partisan motivated attacks on voters, or on election officials. Voting rights has been a locus of civil rights fights over many years, and centuries, in this country. We know, for example, the false claims made about election workers in Georgia. I don't have to say the allegedly false claims, because Rudy Giuliani, last week, admitted that they were false [unintelligible 00:32:06].

Brian Lehrer: In a court filing, right? They're suing him, those mother and daughter, Black Georgia election officials who, of course, we've seen the soundbites so much, them saying, oh-- Rudy Giuliani said they were passing around thumb drives with phony votes as if they were vials of heroin and cocaine, even making the comparison to heroin and cocaine, that they were passing, is racist.

Michael Waldman: It wasn't very subtle.

Brian Lehrer: Not at all. He knew who his audience was, that he was playing to, I guess, because it was really a political charge more than a legal charge, just to continue to whip up the public. Maybe that's one of the reasons why Giuliani is one of the co-conspirators in this indictment. They, just giving people background here, Shaye Moss and her mom Ruby Freeman, filed a civil suit against Giuliani, a defamation suit, and he basically admitted in this court filing, just last week, that, yes--

He's not saying he is liable for defamation, but yes, he did defame them by saying that false thing in front of television cameras and everybody. That's a little more context on that, but keep going on that.

Michael Waldman: There's been, throughout history, use of federal laws to protect voters, election officials, and the integrity of elections. There was the Ku Klux Klan Act, a lot of these date from after the Civil War. This, I think, needs to be seen in the context of that. This is a legal attempt to defend the free and fair elections that people care about so much. In other words, it isn't one of the things that's so powerful about how the indictment was laid out.

They were, of course, quite careful, as Andrew Weissmann and others have pointed out, to respond to, or at least address, the defense. You now hear over and over and over again, not just from Trump, but from co-conspirator number one, Giuliani, oh, this is just my 1st Amendment right, to show these were actions, but that this was an attack on the American democracy and part of the legal standard that they're working to meet in this indictment.

The January 6th committee, which laid out so much of this, did a really good job of showing this too, was that Trump knew it was a lie in the sense that everybody around him, everybody who he had reason to listen to, everybody who he hired to tell him what the facts were, told him, "No, you lost the election." He went forward with these claims because he thought it was his way to undo the peaceful transfer of power, and clinging to office, not because he genuinely believed it.

His defense, not as a legal matter necessarily, but his defense here is almost like an insanity defense. I believed it, even though it wasn't true, so therefore, I couldn't have had the criminal intent, because I really believe this nonsense. If you recall Sidney Powell, who was one of the alleged co-conspirators, who was the lawyer, who was always promising to file the really big lawsuit, called The Kraken, that was going to blow the whole conspiracy open.

Who, even the Trump campaign quickly concluded was erratic at best, when she was sued by one of the voting machine companies, her legal response was, "Oh, no reasonable person could have believed this nonsense."

Brian Lehrer: No reasonable person could have believed me, she was saying, as a defense, in a [unintelligible 00:36:16].

Michael Waldman: Therefore, it wasn't really slander or liable, because it was obviously absurd, what I was saying, because I assume that Trump's defense will partly be, "Oh, look, here's five examples of him insisting, 'Oh, really, I did win.'" Both the indictment and the January 6th committee make a pretty strong point of saying, by any reasonable standard, that we would apply to anybody else, who we didn't think was delusional, that he had to know the facts.

He knew what he was doing was a lie and was just a pretext to clinging to power and undo the Constitution. When I talk about the big lie on trial here, this really didn't start with Trump. The assault, in many ways, on voting rights, the claims of voter fraud without evidence, have been with us, growing and gathering momentum for years, and has been a strategy across the political spectrum from the right.

We always thought, I always thought, it was important that people not see this as, oh-- On the one hand, some people say this. On the other hand, people say that it's not a claim, it's a lie. It's a lie designed to restrict people's right to vote. I think that this indictment with force, clarity, and majesty, makes that case.

Brian Lehrer: One of the most interesting things to me, that you've written in recent days, is that these conspiracy theories are still being used to justify changes to voting and election law all over the country. You are drawing a more than Donald Trump's defeat in 2020 through January 6th timeline here. You're saying Republicans have been using big lie-type election fraud theories to restrict the right to vote. I guess that goes to certain kinds of voter ID laws, limiting different ways that people can vote, and things like that.

There's a through line here, that Trump, in the way you are contextualizing him, learned from, picked up the ball, and ran with, and you say these conspiracy theories are still being used to justify changes to voting and election law all over the country. Can you give us some examples of that, still going on today?

Michael Waldman: Yes, they are the only basis for these laws that are being pushed. Last year, after January 6th, after the insurrection and the election, you had 19 states passed new laws, making it harder to vote in one way or the other. Now, it's important to note, some of these were worse than others. A lot of them were pushed back in the legislative process, or courts have blocked them.

They range from laws in Florida, gutting that state's landmark ballot initiative, which restored the right to vote for people with past criminal convictions, to laws in Arizona and Georgia that imposed new restrictions on how people could cast ballots, or how people could cast absentee ballots. The push, although it hasn't been successful in a lot of places, is to end vote by mail, on the theory, or really radically cut it back. You've seen places and drop boxes, which is the way people vote by mail.

Look, I think it's an important thing for those of us who do care about the right to vote, and an equal democracy, to recognize that when you think about the 2020 election, there was a lot of change, very fast. If you think about the experience that most people in the country have, of both the pandemic, the suddenness of it, the sudden need to change voting rules, to make it so people could have a free and fair election, the fact that the number of people who voted by mail, although--

Again, it's mostly not by mail, it's by Dropbox, doubled in one year, but that was actually a huge success. You had the highest voter turnout. Despite the pandemic, you had the highest voter turnout in 2020, since 1900. As the indictment points out, Trump's own Department of Homeland Security said it was the most secure election in American history.

Brian Lehrer: That's in the indictment, by the way, Jack Smith cites that, that Trump's Homeland Security Department told him. These are Trump appointees, currently in office, told him that it was the most secure election in American history, and still, he perpetrated the big lie.

Michael Waldman: Well, and as the indictment points out, his response was to fire the official who said that, because it was inconvenient, at the very least, that he was saying it, Chris Krebs. These fears of fraud are the basis for so many of these laws. The Supreme Court, even though it upheld the Voting Rights Act in its use on redistricting cases, in a case called Brnovich in 2021, really weakened its use on cases involving voting.

This is the basis for a lot of these changes, these pushbacks, that one after another, they make it harder to vote. We heard Cleta Mitchell, who doesn't seem to have been one of the co-conspirators, from what we can tell, but was on the call with Trump when he called Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia Secretary of State, and said, "Find 11,000 votes," and also threatened him in effect with criminal prosecution.

Cleta Mitchell is a leading Republican election lawyer, and recently, there was a leaked tape of her saying, "Oh, now we've got to go after students," and using the same arguments. They've moved on to student voting. This didn't start last week, you'll remember Trump had a voter fraud commission at the beginning of his administration.

Brian Lehrer: We remember, or we forget that in 2016, when he won the election but lost the popular vote, he claimed that he would have won the popular vote, if it were not for fraud, because he couldn't stand even that loss. Even though he won the electoral vote, and everybody said he was duly elected, he couldn't stand that on his record. He had to look like he won everything. He claimed there was election fraud in the popular vote, and impaneled that fraud commission, and they found nothing.

Michael Waldman: They found nothing, and imploded. There's even a scandal that has fallen down the memory hole, not from Trump, but from the George W. Bush administration, where the political folks at the Justice Department and White House ordered US attorneys around the country to prosecute voter fraud. These are all Republican prosecutors, these US attorneys, when they said, "Well, there isn't any. We looked, there's nothing to prosecute."

A bunch of them were fired, or forced to resign. It was enough of a scandal that the Attorney General of the United States, Alberto Gonzales, was forced to resign.

Brian Lehrer: That's right.

Michael Waldman: This notion of using phony notions of voter fraud as a way to push political goals didn't start with Trump, but it really is squarely on every page of the indictment.

Brian Lehrer: As we hold back the layers of this surreal onion, what you're really saying is that Republicans have used fake suspicions of voter fraud to pass laws that enabled real voter fraud, as we saw in Trump's big lie. Let me get one phone call in here before we run out of time. Obviously, this is not a book interview, but I will note that Michael Waldman has a new book called The Supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America.

I think our caller, Greg, in Chelsea, in a certain respect, is going to tie this news interview together with some ideas that might be in your book. Greg, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Greg: Good morning. Am I correct that the last step in actually prosecuting Donald Trump is that we need one of his Supreme Court nominations to join us, to uphold the lower court's ruling? Would you go through the likelihood that Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Island could actually join us?

Brian Lehrer: Amy Coney Island. That's a funny-- [chuckles]

Greg: I'm sorry.

Brian Lehrer: Amy Coney Barrett, but that's hilarious.

Michael Waldman: Whether it was a deliberate Freudian slip, or just a [unintelligible 00:45:40]-- I can't unhear it.

Brian Lehrer: That's right. August, in New York City, Coney Island on the mind-

Michael Waldman: Exactly.

Brian Lehrer: -but that's so far. Talking about the long game, Greg is really playing the long game here, this is after convictions and appeals that would be held up, and then some kind of appeal, on some kind of grounds. Can you even speculate what they would be, all the way up to the Supreme Court?

Michael Waldman: Well, look, any federal court, certainly, one can expect a potential appeal to this Federal Appeals Court and the Supreme Court. This one is obviously a pretty big deal, and I wouldn't be surprised if there were appeals going up, if Trump is convicted. A couple of things are interesting on this. First of all, in 2020, at least, even the conservative supermajority of this court, which I write about in the book, who are pushing hard to move the country far to the Right, as fast as they can, they didn't really lift a finger to help Trump.

Trump kept saying, "Oh, I need Amy Coney Barrett on the Supreme Court, because they're going to decide this, and I want my justices on the court." He was quite explicit about it, but they swatted away these cases at the time. Interestingly, one ruling they made this past June, that was a very good ruling, was on the independent state legislature idea, the notion that state legislatures have exclusive power to set election rules without checks and balances from state constitutions and state courts.

There wasn't really just about the presidential races, but that was a crackpot idea, with no basis in history or law, but it had really been floated most vigorously by the Trump campaign in the middle of this conspiracy, in December of 2020, and January of 2021. They are more ideologues than Trump people. Having said that, you can't count on anything. It is a big deal. It is unprecedented. There's a reason we should be a little queasy about the idea of prosecuting a former president, or a president, for actions he took while in office.

It's a big step. It's never happened before. I think the magnitude of the assault on the Constitution and democracy merits it, but this is not an everyday run-of-the-mill prosecution. The argument you hear over and over again now, from Trump's lawyers, Giuliani's lawyers, and others, is, "Well, this was just my right in the 1st Amendment to say these things and push these claims."

As you've discussed earlier, with Andrew Weissmann, the indictment works hard to say, "No, no, no, no, anybody has the right to say these things. This is all about actions," but that will still be their argument, at the very least.

Brian Lehrer: All the way up to the Supreme Court, perhaps.

Michael Waldman: Yes. The Supreme Court swoons when they hear 1st Amendment arguments, if they can be used for right-wing goals. I think that it's very hard to get a criminal conviction overturned. Of course, if Trump is acquitted, there's no appeal. It's not like the government can then go appeal, but I think that it wouldn't be at all a surprise if some element of this ended up at the Supreme Court, but in the course of a criminal appeal of a conviction, rather than a Bush v. Gore type major political ruling.

Brian Lehrer: Michael Waldman, President and CEO of the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU School of Law, and author of a new book called The Supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America. Michael, thanks so much.

Michael Waldman: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.