Today's Renaissance

( AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. After the police killing of George Floyd a year ago today, it's not just been policing or criminal justice reform advocacy that have changed, Washington Post columnist, Perry Bacon Jr., writes, "It became more untenable to have no or few Black people in most industries and professions." In fact, using the author Ibram X. Kendi's term, he writes, "We are in the midst of a Black Renaissance," that he says white people and everyone else can benefit from too.

Perry Bacon Jr. who some of you may know from his database journalism at the website FiveThirtyEight, just joined the Washington Post this month as their newest columnist. Perry, welcome back to WNYC, and first of all, congratulations on being a Washington Post columnist. You know we loved your stuff at FiveThirtyEight, so I'm so psyched for you that you're a full-fledged Washington Post columnist now, that's very exciting.

Perry Bacon Jr.: Brian, I appreciate that, and thanks for having me. I've always enjoyed being on the show and I'm excited about my new job, but also sad that I'll have fewer polls and charts, and numbers in my stories than I used to.

Brian Lehrer: The term Black Renaissance in the title and lead line of your piece that you attribute to Ibram X. Kendi, what's the big picture of what that means in 2021?

Perry Bacon Jr.: What Ibram is talking about, and I want to credit him with that idea and I agree with, is that if you look at a lot of high-level feed, if you look at a lot of- we're seeing the Oscars, if you look at the best selling books right now, Isabel Wilkerson and Ibram Kendi himself, if you look at comic book writing has more Black people in it than before, movies, entertainment, but even the head of MSNBC, the head of ABC News, both are Black women now. The head of the Ford Foundation is a Black man.

If you look at a lot of fields, that's the high levels but if you look, we had an old world where I think you had a Michael Jordan, you had an Oprah, you had a Barack Obama obviously, there were a small number of fields where I think there were a lot of Black people at the very front, but in terms of like managers, people who are in the hierarchy, people who hired others, I think you're seeing more of a Black presence in those roles in terms of the people who actually manage the organization.

I think at the front level roles, you're seeing more Black people in a wider range of fields in entertainment, athletics, and sports, and that's what I'm getting. I don't have a data set to prove this, but I think that's what I'm experiencing and I notice in part by friends I talked to at companies like in Silicon Valley, or like in the media, there's just a greater urgency to have a more and more than one Black person and a diversity of Black people at the company and in major roles now.

Brian Lehrer: Perry Bacon Jr. without a dataset is definitely a new concept, but the heart of your column is about what's known as the pipeline problem in the context of what you were just describing. What is the so-called pipeline problem?

Perry Bacon Jr.: I've been working professionally for 20 years and in the fields I've been in, which is mainly journalism, but also I'm in politics as I'm covering it very closely. In a lot of fields, you've had this narrative for a long time is that we would love to hire more Black people. We'd love to get near 13% or even more than that, but we can't find the right, the qualified people, that the pipeline is broken. The idea being Black graduation rates are not high enough or the public schools aren't good enough or there aren't enough Black students who study engineering or journalism or whatever.

For a long time, you heard these kinds of ideas for industry X or company Y wants to hire Black people but we can never find any. I always found these to be a bit misleading. There are something like 40 million Black Americans in the country, hard to imagine there's a ton of jobs where not one Black person is qualified. What you've seen over the last year is a lot of companies, often with their white employees have been pushing them, hey, we don't have a lot of diversity here. What is the deal?

Pretty much every day now I read this, I read about a company that is trying to hire at HBC, historically Black colleges, are trying to diversify in their hiring process, are trying to rethink their hiring process, meaning that this idea that there were not enough qualified Black people was I think always wrong-headed.

I think the more idea was companies wanted to hire who they always wanted to hire, which often was the people in their current stream of hiring, which was Harvard grads or people the CEO knew or people the CFO knew, and not really looking at a broad perspective about who actually can do this job. If we define this job in a way that is normed around maybe a white guy as opposed to thinking about this drive in a broader way.

Brian Lehrer: You note in your column that the pipeline problem narrative became even stronger in 2008 after Barack Obama was elected president. How did the two things relate?

Perry Bacon Jr.: I think that I remember in that period, a lot of times I talked to people and they'd be like, obviously, the country found the Black person who was qualified and made him the president. Obviously, there cannot be any kind of racial barriers to a regular Black person being hired at this company. The country is beyond that idea. If only you're a Barack Obama style, then it actually was if only you're a Barack Obama style Black person, then you too can get this job.

The problem is that A, Barack Obamas were the most talented people in the world who had a degree from Columbia and has a degree from Harvard Law School, and also that Barack Obama, and I myself in this group, was a certain Black person who is very well educated and also very able and willing to adapt to what I would say are at times norms of our society that are often what I would say are white norms in a certain way.

I think that people like Barack Obama, this is a credit to him and this is something that I thought about a lot too, is are able to adapt in I think the term is often used to code switch and so on. You don't want to make that a hiring norm. We should hire Black people who are good at their jobs in all kinds of ranges and not necessarily look for a lot of the can we get the Obama type. That may not be exactly the right metric to describe who is qualified, who is Black.

I think now, like you said, like I said, you're getting more people hired who maybe have dreadlocks or maybe who talk a certain way that sounds more Black or maybe who went to Howard instead of Harvard. I think you're seeing a rise of people who I think are different than that Obama-ish norm.

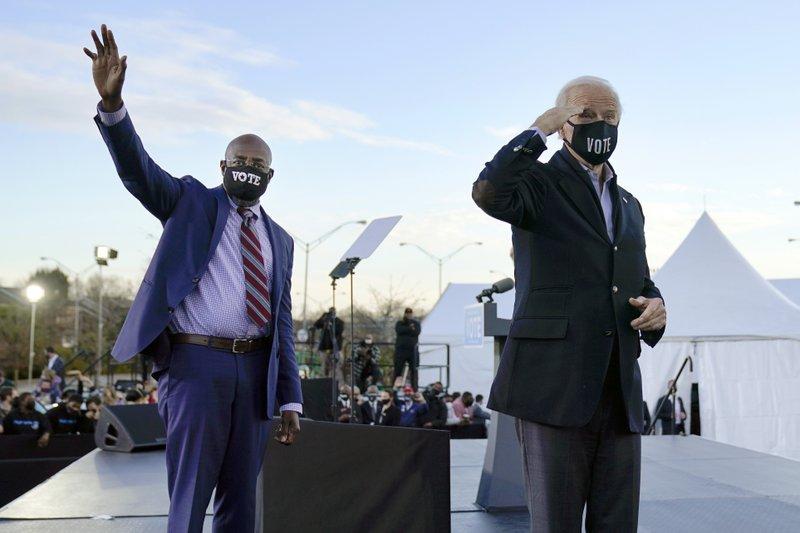

Brian Lehrer: Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. with us. Another example you use in the column along those lines is the Democratic Party recruiting Raphael Warnock to run for one of those two Now very famous US Senate seats from Georgia that the party won in the special elections in January to take a majority in the US Senate. What's the Senator Warnock story in this context?

Perry Bacon Jr.: It's two things. It's first of all that the Democrat, I think the electorate in Georgia is about-- The Democratic electorate in Georgia is about a half Black. The plurality of Democratic voters, people who vote for Democrats in Georgia are Black. There were two open Senate seats as you recall. I think a decade ago, the Democrats would have done one of these we need to find an electable person, and electable often in the South for Democrats codes is we need to find a white guy who seems palatable to "swing voters" who were always of course white.

That is what the Democratic Party used to do. I think in this new, I think in this post-Black Lives Matter, also the Stacey Abrams campaign did very well there, but I think in this post-Black Lives Matter era, the Democratic Party was pretty aware they would have got a lot of criticism if they ran two white guys or two white people in a state like Georgia where the majority of Democratic voters are Black. They went out of the way to find a Black candidate, which I think is important. Jon Ossoff, a white candidate, also ran so they had a Black candidate and a white candidate.

I think the important part as well is that you had a period of time after Obama ran where there was a search for a lot of people who I think are very good politicians, Cory Booker among them, who were often the person again, who went to an Ivy League school, who's their environment is kind the elite white settings in a certain way. I know Corey Booker was the mayor of Newark, so I'm not trying to diminish his other parts of his biography but I think Warnock is a person who went to Morehouse and then went to seminary and then has spent his time running a majority Black church.

This is that unusual, that background is one that is more, it is not necessarily Obama-ish in a certain way. It's not an Ivy League school background. It's not credentialed in the way we often think of in DC circles, but Warnock went to seminary, went to Morehouse, these are great education, and then ran a Black church for a while, which is a different kind of achievement than teaching law at the University of Chicago as Obama did, but not a worse accomplishment.

In other words, there are lots of Black people qualified to do things. I think Warnock's been an excellent Senator so far and is quite intelligent and quite good at his job, but when you get away from that we're looking for the next Obama-ish person, it expands out the opportunities for Black politicians and really every kind of politician.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, really interesting. I think another really interesting thing from your column is that you write, this casting of a wider net is also better for, say, white community college graduates or Latino graduates of state schools, as opposed to small elite private institutions. How does that follow that it would benefit certain kinds of white people, for example, if the focus this last year leading to what we've been discussing so far has been on racial justice for Black Americans?

Perry Bacon Jr.: My argument is for a long time as a society, this idea of there's a pipeline, the idea is these jobs are so hard to fill, we can't hire any Black person to hire for the job. I think the implication is obvious is embedded in there is like lots of people cannot do this work. This work is too hard. Working at this institution or being an engineer at Google or writing for the Atlantic, it's too hard for almost every Black person.

I think the implication is also is that it's probably too hard for most white people, most Latinos, and most Asians too. If you have to have a degree from Yale or a degree from Harvard, I went to Yale, so I'm open about how this bias helped me in a certain way. The idea is if only a few people from a few schools with a few backgrounds can qualify for a lot of jobs, that's going to exclude everybody, most people did not go to Yale, white, Black, Hispanic, Asian, et cetera.

Most people did not go to Ivy League schools, a lot of people went to the community colleges. Once you get out of this mindset that we have a sort of a scarcity of talent and that very few people can do these jobs, and get to a mindset, which I think is true, which is a lot of people, I'm going to be honest, Brian, I think a lot of people could host a radio show.

I think a lot of people can be Washington Post columnists. I think that you and I have lucked into these jobs. We've also worked hard at them, but I think when we move our society from a one in which there's a view that we have a scarcity of talent, and one toward a view that we have an abundance of people who can do lots of things, and we're trying to maximize that talent, I think that's a better society for everybody.

Brian Lehrer: Could that thinking backfire though in racial justice terms, because we know that less qualified white people are often perceived as more ready than more qualified Black people, right?

Perry Bacon Jr.: I think if we're trying to open up opportunity, what I might-- Let me give a specific here. If I was trying to reform like Yale University, my goal would not be to say, I figured out some formula where more Black people should go, so we should increase the Black number and decrease the white number. What I'm probably more, if you've got to my actual views of this might be more, we should increase the number of, Yale is saying only 1200 people should go, but in my view, I'm guessing there are 5,000 or 10. I'm not sure how big Yale can be, but I think there's probably more qualified people.

What I'm advocating is less that we replace Black for white or white college grad, white non-college grad replacing white person with colleges, and more to expand the number of jobs we have and the opportunities we have, period. I agree everyone can't have a radio show, so I've got to think about this in some form, but I think part of the question is, if a lot more people are qualified, I think it raises questions about maybe, how do we increase the pie as opposed to redistributing in different ways.

Brian Lehrer: Last question on this, you make the case that this Black Renaissance that you write about shows the path to an American renaissance, and we should take that path, not just because it's more fair to people who've been marginalized by prestigious institutions, but for those institutions themselves. Want to make that case for any skeptical hiring managers or college admissions officers out there in our last minute?

Perry Bacon Jr.: Yes. I read the media a lot, so I'm very aware of that, but I just think the world we're in now where we have a greater diversity of voices, and unless they end up in the racial context, I see more graduates of Howard and Morehouse writing pieces. They're probably the same number of Yale and Harvard graduates, but we have more Black people with different experiences than mine, or I would say Barack Obama's writing pieces in publications.

I think that the country has learned a lot about racial issues in these last three years because we have Black people with different experiences, and I would say Black people with more challenging experiences often. Yale graduates like me are probably not the best people to tell the challenges of being Black in America. I think we've benefited from having a broader people telling their stories.

My guess is that would apply to white people, Hispanics as well in the sense that if we have a greater diversity of storytelling, we're going to have a greater diversity of experiences that are being expressed. I think we'll end up with better quality work if we have more people doing that work and more perspectives involved in that work.

Brian Lehrer: Perry Bacon Jr. many of you knew him from his work at FiveThirtyEight. He's now a Washington Post columnist as of this month. As I said at the beginning, for our listeners just tuning in, we were already Perry Bacon fans here at the Brian Lehrer Show, and we always have enjoyed you coming on the show, and we look forward to you continuing to do so in your new role at the Washington Post. Thanks a lot, and again, congratulations.

Perry Bacon Jr.: Thank you so much, Brian. I appreciate that.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.