TikTok's Algorithm

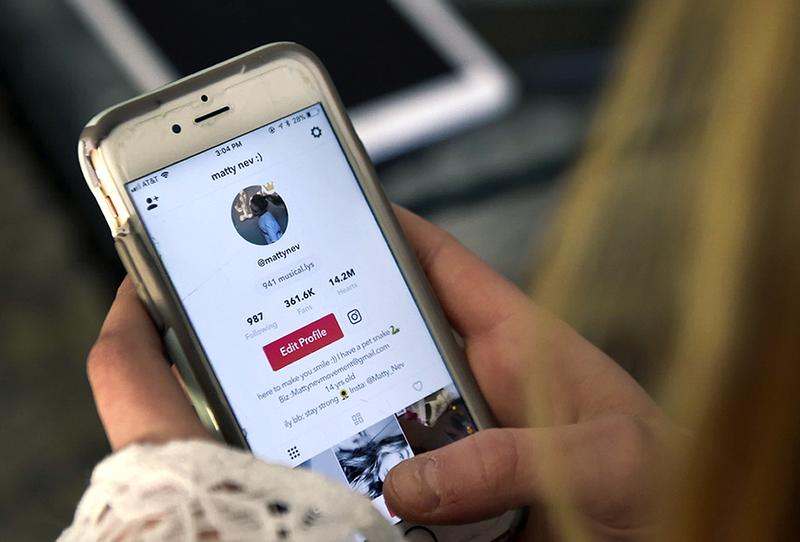

( AP Photo/Jessica Hill )

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. To close out the show today, we'll talk about TikTok including your calls on this question, does the TikTok algorithm or recommendation engine know you better than you know yourself, and who does TikTok have you pinned down as? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Does TikTok know you better than you know yourself or if not, who does it have you pegged as? 212-433-9692.

We're going to talk about this with John Herrman, contributing writer at New York Magazine's Intelligencer. He's their tech columnist. In a recent article about this, Herrman challenges the perception that TikTok's algorithm is an all-powerful secret sauce that can read your mind better than users know themselves. Instead, he argues that the real mystery lies in the user's willingness to repeatedly engage with the platform, even if it feels like being a test subject in exchange for entertainment. The article also explores how TikTok's Chinese ownership has shaped the scrutiny and perception of the platform. John Herrman, again, tech columnist for New York Magazine's Intelligencer joins us now. Hey, John. Welcome back to WNYC.

John Herrman: Thanks so much for having me.

Brian Lehrer: So not the algorithm itself, something about the users' comprises the secret sauce. Want to explain?

John Herrman: Yes. The TikTok's big innovation was fore fronting recommendations. If you think about Facebook in the old days, you knew why you were seeing things. You were friends with certain people. You followed certain topics or pages. Those things would show up a lot because that was the arrangement that you made. Over time, Facebook and other platforms started making recommendations from elsewhere based on invisible calculations that you weren't really a part of.

TikTok jumped ahead a few years in a trend that was already taking over the industry and said, "What if we just showed people stuff, recorded what they liked, recommended more things like that? What if we showed them some wild and crazy things and recorded that as well and built big statistical models around people's behavior?" This is something that's extremely commonplace on your phone and also just in real life, but TikTok pulled of a really interesting trick in making that the core of the app experience and making it feel a little bit like magic.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Another way to put it, you write, "Using TikTok was for me defined by encounters with the randomness combined with a sensation of surveillance rather," than an all-powerful algorithm that you knew better than yourself. Can you talk about the randomness part of that a little more?

John Herrman: Yes. When you use TikTok, especially if you start a new account, you'll see a bunch of stuff that's just sort of strange, stuff that will feel like a non-sequitur or a total surprise. Quickly, you'll see evidence of surveillance, meaning if you watched some cooking videos, you'll start to see more cooking videos. If you watched cooking videos about Mexican food, you'll see more cooking videos about Mexican food, and so on and so on.

At the same time, you'll always be shown a pretty sizable portion of just weird stuff, stuff that you didn't seek out or didn't signal directly that you wanted to see. That's TikTok testing whether or not you'll engage with this other thing too. Building a bigger and bigger profile based on your behavior, not based on a list of things that you've told it you want to see. That's the feeling of surveillance and that contributes to the feeling of randomness, but that feeling of randomness combined with the really direct feedback that users get creates this illusion of the computer, of TikTok knowing something about you that you don't yet know about yourself. If it starts showing you videos about cars, and you don't own a car, but you've watched a lot of those videos, it feeds this idea that, "Wow, it knew something about me," when what really was happening was it was just testing it out and it turned out that you did want to see some car videos.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Test subject as you say. Janet in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Janet.

Janet: Good morning. I was talking to a friend who lived in China, and he was telling me that in China, TikTok is very educational and not what we have in America. I thought that was very interesting. I think I've heard that before. I'm not really sure if it's true. I'd like him to-- if you'd like to comment on that. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: John? Thank you.

John Herrman: Before TikTok in the United States there was another Chinese app called Musically which was lip syncing and dancing and really popular with very young children, but it grew out of an educational app that failed in the US market. Its founder went on to then run TikTok. That same founder mentioned that in his view at the time, the US represented a major opportunity because in China, young people were focused on their studies. They were very busy, they were very stressed, they didn't have a lot of free time to consume frivolous content, whereas teenagers in the United States, and granted this is a stereotype from afar, but this is someone with extensive experience in the US tech industry as well, American teenagers maybe had a little more time to just post silly stuff, and perhaps TikTok is the proof of that theory.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, well, I was thinking of you last answer about not having to be a car owner or a car enthusiast, but they'll just test you with something random like, for example, things about cars, and maybe you like watching it, even if you don't own a car, and so you get more of that. Listeners, how about this for you TikTok users, what does your TikTok for you page look like, and how different do you think it is from when you first started using TikTok? TikTok users, how about your for you page on TikTok, what does it look like for you, and what does it make you think about the algorithm or for that matter about yourself? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 for John Herrman, tech columnist for the New York Magazine's Intelligencer and of course, you can text as well as call, 212-433-WNYC, 433-9692.

To get more into the politics of TikTok, your story notes that critiques of TikTok beyond its algorithm were familiar. Like Facebook, Instagram and other platforms, it took heat about child safety, its addictive nature and other potential risks, but with TikTok, critiques have always been, as you write it, "Informed by the question of foreign ownership." In that context, what does it mean that TikTok ones embraced this narrative of an all-powerful algorithm? Does that land differently in the American psyche when we know it has connections to the Chinese government?

John Herrman: I think it does. One of the remarkable things about TikTok that I remember when it first started taking off was how closely it was mimicking other tech platforms. It was a compilation of all the latest trends in social media, the content recommendation, the way that the interface worked. It was new, but it was also more of the same. This was at a period when Facebook and YouTube, for example, were under intense scrutiny for a wide range of issues, but specifically for their algorithmic recommendations.

YouTube was being accused of radicalizing people and sending people down these algorithmic rabbit holes. Facebook was being accused of tearing the nation apart with strange recommended extreme content all across the platform. Then here was a platform that showed up and said, "We're just going to do that all the time. We're going to make that controversial piece the core centerpiece of our technology." It turned out that people really liked that.

That backlash for Facebook, for example, if you think about Mark Zuckerberg defending his platform after the 2016 election, was something that they could just batten down the hatches, deal with and then let dissipate. With TikTok, the idea that there is an invisible algorithmic recommendation system, it's making billions of value judgments about content, showing things to hundreds of millions of people, is easy to cast in a more sinister light when it has connections to a foreign government with whom the US government has often antagonistic relations.

In the way that the algorithmic stories of Facebook and YouTube helped build those companies reputations and bolster their stock values, the algorithmic story of TikTok as the magical thing that really knows you well, that was getting into our heads in this really unique way, is easy to flip into an even more sinister story than just, "They want more engagement. They want more money or whatever." Now, it's part of potentially depending on your view, a foreign plot, a propaganda campaign. It's very easy with an algorithm, and an algorithm with a black box to then weaponize the platform rhetorically, I mean, to say this is actually a weapon or this is like a drug because it otherwise has been kept secret and mystified for so many years already.

Brian Lehrer: Listener writes, "This is Mandy in Bushwick. My TikTok algorithm has many videos about rocks and geology. TikTok taught me that I'm into the formation of lakes and rivers and rock sedimentation." Thank you, Mandy. Yes, we are in this moment, as you're just saying, where Congress just passed this law that's going to force TikTok to sell, the current owners of TikTok to sell because of their connections to the Chinese government or TikTok will be banned in the United States in less than a year. Tim in Scotch Plains is calling in about that. Tim, you're on WNYC. Hello?

Tim: Hey, thanks for taking my call. Interesting subject. Well, the government doesn't like any narrative that they can't control, and that's what this is all about. The internet is all sorts of informations, free flow of informations. Some of it's wrong, some of it's correct, and they want to shut it down. How about the US government goes around and with caller of the revolution and uses the internet to overthrow governments? I mean, come on, it's [unintelligible 00:11:18] they don't like to push back. They don't like their lies being challenged.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe, maybe, but, John, the pushback to that might be well, so does X get used that way, so does Facebook get used that way. Your thoughts?

John Herrman: Yes. I think it is mostly useful to think about TikTok in terms of the other social media platforms. I do think that the effort by some critics, but also by legislators, and especially by some of TikTok's competitors to make it seem categorically different is sort of makes this harder to talk about, harder to think about, and harder to have a sensible position on.

Certainly, there's some desire by some lawmakers to just shut down speech that they don't like, but generally, they're making a more complicated argument about foreign influence, about privacy, about not really knowing how these platforms work. These are all, again, reasonable criticisms and questions concerning all the social platforms, but the question of Chinese ownership and also TikTok's particular emphasis on the algorithm, on the secret sauce, on this mythmaking about being this artificial intelligence company, that is all made that much more difficult to talk about and in the end, I think a lot a lot harder for TikTok as a company.

Brian Lehrer: That is where we're going to have to leave it. That certainly went fast. We don't have time for any more of your stories about how the TikTok algorithm knows you better than you know yourself or it doesn't. John Herman, technology columnist at New York Magazine's Intelligencer. His story, The Secret Weakness of TikTok’s All-Powerful Algorithm. Thanks a lot, John.

John Herrman: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: That's The Brian Lehrer Show for today. Produced by Mary Croke, Lisa Allison, Amina Srna, Carl Boisrond, and Esperanza Rosenbaum with help from Briana Brady today. Zach Gottehrer-Cohen edits our National Politics podcast. Our intern this term is Ethlyn Daniel-Scherz. Megan Ryan is the head of live radio. Juliana Fonda at the audio control. Stay tuned for All Of It.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.