Thursday Morning Politics: Race, Class and 2024 Election Politics

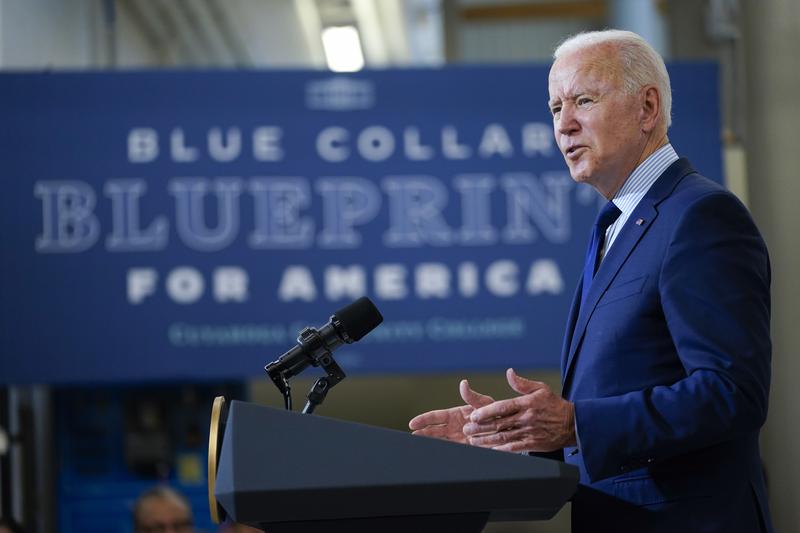

( Evan Vucci / Associated Press )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. The Supreme Court ruling last week banning affirmative action by race might lead to selective colleges trying to integrate more by class, that's still allowed. Class is an imperfect surrogate for the Black Americans left behind by 400 years of structural racism but there is some overlap there and it's legal to count freshmen heads by whatever we mean by class. That's one example of how race and class intersect in American politics, sometimes aligning, sometimes in competition with each other.

New York Times correspondent David Leonhardt writes a lot these days about what he calls the class inversion of American politics. That is Americans with college degrees are increasingly likely to vote for Democrats. Americans without are increasingly likely to vote for Republicans. That does pertain mostly to white voters, so again, race and class are imperfect surrogates for each other, but non-college graduate Latinos, and to a lesser extent non-college degree Black voters also vote Republican more than they used to. Why is this politically important? Well, in one recent article, Leonhardt noted that most US voters, about 60%, do not have college degrees and they live disproportionately in swing states.

The way Leonhard crunches the numbers, if President Biden wins exactly 50% of the non-college vote next year, he will almost certainly be re-elected, 50%. If he wins 45%, just 5 points less, Leonhardt says he will probably lose. Leonhardt has been writing about how both Democrats and Republicans might compete effectively for that potentially decisive 5%. David Leonhardt joins us now. He writes the daily newsletter from the New York Times called The Morning and contributes to the Sunday Review section. David, thanks for joining us today. Always good to have you. Welcome back to WNYC.

David: Thank you, Brian. It's always a pleasure to be on your show.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start by defining some terms. You seem to use the terms working class and non-college voters pretty interchangeably on one side and college graduates and professional class interchangeably on the other. Can you describe in a little more detail who you see as being in each of those two camps?

David: Yes, and they're not exact. There are folks out there who try to do more careful analyses based on class, sometimes looking at exact job types so that if you oversee other workers, you would be considered professional class. If you don't oversee other workers, and you work in particular industries, you'd be considered working class. Some of the political analysis that I've looked at does that very careful work. It's often difficult to do that and the fact is, if you just use college and non-college, you really see identical top-level patterns. On your show, I know you've talked about this idea of Deaths of Despair, which is research that's been going on for now 10 or 15 years.

This is by two Princeton economists, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who have looked at what has happened to life expectancy among the working class, and they define it by education, because that is what is on death certificates. Many people who do economic work also define it in that way. When you look at polls, we often don't ask people 20 questions about their job, but we do ask them about what their highest level of education is. For broad scale research, really using the four year college degree as the dividing line allows you to do the most in depth analysis. It lines up, not identically, but extremely closely to studies that do try to do the finer analysis.

Brian Lehrer: For example, you wrote about a YouGov poll that compare different hypothetical Democratic Party candidates for a group to find swing voters, and it found the swing voters preferred Democratic candidates who had been a teacher, a construction worker, a doctor, or a nurse before entering politics. The least popular candidate professions were lawyer and corporate executive. Aren't so many politicians from both parties lawyers and business people?

David: They are. I mean, often voters have to choose between two lawyers or one lawyer and a corporate executive. That study actually used the finer definition of class. It used the definition of class that was based on job types. One of the things, one of the consistent themes here is that on economic questions, swing voters and working class voters, and there's a lot of overlap between those two groups, tend to be left of center. I don't want to exaggerate this. They don't identify as socialist, but they tend to be left of center. Most of them are in favor of increases in the minimum wage, which is why when the minimum wage goes on the ballot, even in red states, it tends to pass.

They're in favor of expanding Medicaid under Obama again, which is why when that goes on the ballot even in red states it passes. They're in favor of pretty tough populist language coming from candidates like John Fetterman in Pennsylvania. They prefer candidates who don't look like your boss, but might look like your colleague. The flip side of this, and this is the part that is harder for many progressives, is that swing voters and working class voters are more moderate, even more conservative on many social issues than the Democratic Party is. One of the things that the Democratic Party has struggled with is they've basically tried to tell working class voters that they're just wrong to have those views.

They're wrong to be in favor of less immigration, or they're wrong to be in favor of some abortion restrictions, or they're ignorant and they're voting against their economic interests, or even that they're hateful for having these views. That's the wrong way, first of all, to persuade people, and I think second of all, reasonable people can disagree about these things. One of the reasons Democrats have struggled despite the relative progressivism of these voters on economic issues, is that many of these voters just look at the Democratic Party and they see a party that doesn't represent them on many other issues, and that is increasingly the party of college graduates.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, well, let's take an example from that same YouGov poll that you cited in an article. The poll found the swing voters liked certain things that might be considered progressive and others that might be considered conservative, and you were just naming some of them. I'll zero in on two here. They approved of a federal jobs guarantee, which is very Bernie Sanders socialist, but a very effective promise for the swing voters from these hypothetical candidates was to protect the border. Decriminalization of the border was very unpopular, so that's pretty Trumpy or pretty MAGA. My question is, do real life candidates exist who combine those things, especially when many Democrats find protect the border to be racist code for keep out the Black and brown people?

David: There's no doubt that there are some people like Trump who use protect the border as racist code. The notion of protecting the border is not in and of itself racist. One of the biggest mistake that Democrats have made is imagining that inherently, restrictions on immigration are racist. If you go back and you look at the way that Barack Obama talked about the border, he talked about border security. If you look at the way that Bernie Sanders used to talk about immigration, Bernie Sanders would say, "Why is it that all these corporate executives want such high levels of immigration? Is it because they care so much about the immigrants?" Bernie Sanders would say, "I don't think so. It's because they want a large labor supply that allows them to keep wages down."

What the Democratic Party has had a really hard time with on immigration in particular, is understanding that it's not so simple as the country has to choose between a racist policy and a policy that allows everyone who wants to enter the United States to enter. There is no country in the world that allows everybody who wants to enter to enter. When you look at countries like Japan and South Korea, they have very tight immigration restrictions. There's actually really no Democrats who argue that we should have an open border. In fact, they get angry when Republicans accuse them of being in favor of an open border.

Trying to come up with the right compromise where we acknowledge that immigration involves trade offs, I think is something that many voters are eager for. What they hear from the Democratic Party is basically almost no willingness to talk about immigration restrictions, to talk about what were the things that would lead to deportation, and that is a real change. To your question of who combines these things, the answer is Democrats as recently as Barack Obama combined these things, but the party in response to Trump has become less comfortable with talking about immigration in those nuanced ways.

Brian Lehrer: At the same time on the Republican side, Republicans who may once upon a time, like George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan, have made deals to allow people who've been here and law abiding for a while to have a path to citizenship, even the most sympathetic group like the dreamers, those who were raised as Americans but brought here illegally when they were really young, Republicans are against all of that now. You used two Democrats now in Congress as examples of success in that same article. Let me name these names. Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona and Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur of Ohio. Why them?

David: Well, there are more than that, but if you look at another study that was done by Data for Progress, which is a progressive group, they went out and they looked at a whole bunch of the messages that Democrats used in the midterms and then they basically tried to subject these messages to the rigors of a social science test. You give different people in a survey different messages and you ask what appeals to them. The kind of Democrats who have done really well are the kind who have talked about border security, who have talked about the importance of bringing down crime, who have talked in nuanced ways about a lot of these social issues, and who also tend to be really quite populist on economic issues.

This notion that the way to appeal to the American middle is some sort of Mike Bloomberg style, socially liberal and economically conservative, and I have enormous regard for many of the things Mike Bloomberg accomplished as New York Mayor, but the notion that that's where the American center lies is almost exactly flipped. It isn't with the socially liberal economically conservative.

It's much more likely to be with the economically progressive and the socially moderate, and so it's John Federman, it's Marie Gluesenkamp Perez who owns a car repair shop in Washington state and talks about how her own party, the Democrats, is too elitist. It's Sherrod Brown in Ohio who's no one's idea of a moderate. He's very populist and left on economics, but he manages to avoid making his campaign all about these social issues that tell working-class people, "Hey, the Democrats aren't the party for you. Hey, we think you are ignorant. We think you're wrong on all these social issues."

Brian Lehrer: My guest, if you're just joining us, is New York Times columnist David Leonhardt. He writes The Morning newsletter. Some of you probably subscribe to that and writes in the Sunday Review section. We're talking about one of the recurring themes in his writing, which is what he calls the inversion of class, the class inversion in American politics, more working-class people broadly defined, voting Republican than in the past, more professional class or college-educated people voting Democrat than in the past. David, I'm going to ask you in a minute a few questions that challenge the premise.

David: Please.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, help us report this story. Are you part of what David Leonhardt calls a class and version of American politics? Do you consider yourself working class or non-college educated, but more Republican than your working-class parents or professional class and more democratic than your professional-class parents, or any story you want to tell about yourself or people or any question you want to ask David Leonhardt from the New York Times for whom the class and version of American politics is a recurring theme in the Times' Morning Newsletter and the Sunday Review section? 212-433-WNYC is our phone number as always. That's 212-433-9692.

Tell us a story, ask a question, pose a challenge of your own. Whatever you want to do at 212-433-9692. Call or text your question or comment to that number. You cite that today's Democratic Party has come to be associated with the establishment. Establishment in what ways? I'm curious if it's more responsive to various groups who are considered marginalized like Black and Latino and Asian American voters all preferred Biden in 2020, as did voters marginalized by sexual orientation or gender status, including women. I'm looking at stats from the Cornell University Roper Center that say Biden won women by 15 points while Trump won among men. How in race and gender terms does that add up to the Democrats are the party of the establishment?

David: That's a notion that I borrowed from my colleague Nate Cohn, who is the Times' Chief Elections Analyst. It is a somewhat amorphous idea, but if you just look at Joe Biden and look at Donald Trump, which one of them seems to be defending the establishment, and which one of them seems to be challenging it? Now, I do not say any of that as a defense of Donald Trump's attempts to execute a coup, of Donald Trump's obvious racism, of Donald Trump's encouragement of violence, of his constant lies, but if we're just asking ourselves, which one of those two sends a message to voters who don't follow politics as closely as you and I do? Which one is from the establishment and which one isn't?

I think it seems pretty clear that it's Biden who is defending, I would argue, many basic American values, but also feels more like an establishment figure, whereas it's Trump who's trying to overturn what feels like the establishment. Again, it's amorphous. I don't think it's necessarily the most important thing going on here. If you are angry about the way American life is going, if you're frustrated for whatever reason, good or bad, reasonable or hateful, who's the person who seems like they want to upset the apple cart? Well, in 1992, it was pretty clear that George H. W. Bush represented the establishment and either Bill Clinton or Ross Perot represented something like an insurgency. I would say even though Trump was president, he's pretty clearly flipped it so he portrays himself as the anti-establishment politician in a way that appeals to some voters.

Another colleague of mine Astead Herndon who's the host of The Run-up Podcast, he's done a ton of reporting and interviewing voters out there, he said that he thinks that one thing that those of us who follow politics intellectually and analytically underestimate is how much Donald Trump's notion of fun appeals to a certain segment of voters. I do think that segment of voters is predominantly male and predominantly white, although increasingly also voters of color. It's predominantly male, but there is this notion that I do think appeals to some frustrated people. We should talk more about race as part of--

Brian Lehrer: We will, but also about the idea of what actually constitutes the establishment. A lot of Democrats would say that Trump-style conservatives are trying to uphold old things in American life. A lot of undesirable old things by Democrats' views that are more established or establishment than what the Democrats represent. I'll give you a couple of other examples. One is the Cornell Roper numbers show that Biden won voters making less than $100,000 a year by more than 10 points. Trump won voters making more than $100,000 by more than 10 points. Which party did working-class Americans really choose?

David: Well, I would really encourage people to be careful with exit polls. Exit polls are problematic in all kinds of ways. The best work that is done by this is done by groups like Catalyst, which don't rely on exit polls but instead rely on very careful work involving voter files. It takes months and months to do. It's not simply based on an exit poll and so it's not the case. It is absolutely not the case.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, I'm not sure if the Cornell Roper numbers were exit polls. I didn't see them labelled as such so it might have also been a later post-election analysis, but I'm not sure.

David: Okay, if you look, it is very clear based on the most careful work from any source. Nate Cohn has done the best work describing this in the Times. He talks about the many different sources. The latest Catalyst numbers, for example, showed that 59% of college graduates in 2020 voted for Joe Biden. That's the two-way Democratic share. It ignores third-party candidates, but third-party candidates weren't that significant in 2020. 59% of college voters voted for Biden. 48% of non-college voters voted for Biden. Now, education and income don't align perfectly.

It is the case if you think of a classic, more educated, lower-income person or middle-income person like a teacher, they would tend to skew Democratic whereas a classic less educated, higher-income person, maybe like an entrepreneur, would tend to skew Republican. The divide is not quite as stark with income. By any number of measures, it is very clear that large numbers of working-class people have moved to the Republican Party in recent decades and large numbers of college graduates have moved to the Democratic Party. It is also the case that large numbers of lower-income people have moved to the Republican Party and large numbers of higher-income people have moved to the Democratic Party. There are definitely measures when you look at it that show, I think that 10% points is exaggerated, Joe Biden still won a small majority of lower-income voters, depending on exactly where you draw the line.

Brian Lehrer: Doesn't that also bring us back to race as perhaps the crucial demographic in American politics more than this class divide that we've been describing or maybe race plus white conservative Christianity? In so many of these income and gender and other categories, I think Trump won among whites, but lost among Blacks.

David: Yes. I think after Donald Trump won in 2016, there was a big debate among analysts and people in politics in which the debate you could basically boil it down to, was it all about racism? Was Trump's greater ability to win working-class voters than Mitt Romney's, who was the Republican nominee prior to Trump? Was it just all about racism? I think many progressives adopted that analysis. I thought it was problematic at the time, but the evidence has certainly made it look less compelling since 2016. As you mentioned in your introduction, Brian, large numbers of non-white people have moved toward the Republican Party in the last five years.

The shift of Latino voters toward Republicans has been really big. In 2016, again, I'm using the Catalyst data, Hillary Clinton won 71% of Latino voters, very similar to what Barack Obama had won in 2012. In 2020, that share fell to 62%, so Democrats lost 9 percentage points among Latino voters, and that was mostly not about the difference between Hillary and Biden. The big drop in Democratic support among Latinos happened in 2018. We also have seen a big shift among Asian American voters toward Republicans, and New York is arguably the single best place to look at that.

There are just New York neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens that were super strongly Democratic, heavily Asian neighborhoods, that are now about 50/50 or even tipped toward the Republicans. There is even a couple of percentage points in which Black voters have shifted toward Republicans, either in terms of actually shifting, although the numbers are still quite small or in terms of not voting. For progressives who basically would say this is just racism, the only reason any working-class person could possibly support Republicans is because of racism and hatefulness, I would say what explains this large shift among voters of color to the right over the last five years. We see it in Florida, we see it in Texas.

We see people in Texas electing strongly pro-border security Republicans in some cases, or Democrats who talk about immigration in ways that are very different from the way that progressive highly educated Democrats talk about it. I think it's really important for Democrats to grapple with that and ask themselves what could it be that is causing working-class people who have struggled so much more than college graduates by any measure over the last several decades to shift to the right? Are we making a mistake both tactically and morally by saying the only possible way they could vote for a Republican is out of ignorance and hate? I would say the answer is that is both a tactical and moral mistake.

Brian Lehrer: Khalil in South Orange, you're on WNYC with David Leonhardt from the New York Times. Hi, Khalil.

Khalil: Hey. Hey, Brian. Thanks for having me. It's Khalil Gibran Muhammad in case you remember that name.

Brian Lehrer: Oh really? Hi.

Khalil: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: You know each other?

Khalil: David. Yes, we know each other.

David: I don't think we do.

Khalil: I'm a Harvard professor, and I've been listening very carefully to the conversation. I have two simple points to make. One, the notion of economic populism among whites has been the most dominant theme in elites, whether they were the plantation elites or the founding father elites who essentially gave them a little bit more in exchange for embracing their whiteness. There's just no way to not understand everything from indentured servitude to the populist era of the late 19th century without understanding the increasing use of white supremacy as a tool to encourage working-class white people to accept less in terms of the economic pie.

The second point is the point you just made about the attractiveness of the right to people who are of color. There's a very long history, David, of immigrants from Asia, from Latin America coming into the country, surveying the scene, including Caribbean immigrants, and saying, the closer you are to whiteness, the better you have a shot at the American dream. Trump has exploited that by using the optics of people of color, of Black pastors opening his rallies. The truth is that in Latin America, the divide over socialism versus neoliberalism means that people of color also can fight over how to organize an economic system, and they bring those sensibilities to this country. Racism, particularly anti-Black racism, still operates in this context. We have not let that go. I'm done.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, listeners, for those of you who might have recognized the name from the show or elsewhere, but not sure exactly from where, Khalil Gibran Muhammad is a professor at Harvard now as he said, but he used to run the Schaumburg Center that part of the New York Public Library and come on as a guest periodically here in that context when he was in New York plus for some of his writings. It's that Khalil Gibran Muhammad. David, go ahead.

David: I mean, look, I agree with so much of that. Is racism a central part of American history? Is it our enduring shame? Is it a huge part of our society today? Absolutely. The answer to all those questions is yes. Does Donald Trump and do many other Republicans use racism in their appeals? All that is yes. My argument is not whether is racism a crucial part of American society, it undeniably is. Is it the only thing that explains these shifts? I think there is really strong evidence that it is not the only thing that explains these shifts. The question becomes for the Democratic Party, how does it staunch its losses among working-class people, including working-class people of color?

One possible answer to that is to tell them that the only thing that Republicans have to offer them is racism. I don't think that's been particularly successful if you look over the last 20 years or the last 5 years. To me, I think it's worth being introspective about what are ways in which the Democratic Party alienates working-class people that isn't simply a story that puts the Democratic party on the side of truthness and morality and anybody who votes conservative on the side of ignorance and hate. I'm asking for that more nuanced analysis of this.

Brian Lehrer: Hey, Khalil, since I have you, if I can put you on the spot here a little bit, and since you're at Harvard, which obviously lost that affirmative action case at the Supreme Court last week and coming full circle to how I introduced the segment in the context of that decision, David wrote an article called Social Class Is Not Only About Race and noted that class diversity has been a blind spot for many colleges. I wonder if you're privy to any buzz at Harvard or that you can reveal that class because it is so disproportionately African Americans who are in lower class categories, however you want to call that, certainly by income, working class type profession parents, things like that. Can it be used? Do they intend to use it as a surrogate for race to the extent that it can legally in the eyes of the Supreme Court replace what's been lost?

Khalil: I hate to disappoint. I am not privy [laughs] to the plan. I haven't been at the strategy table, but I can say that Harvard will likely think about the test as the less relevant issue for moving forward, which was the basis of the claim of disparities between Asian applicants and Black ones. You remove the test from the equation, you've got a universe of possibilities to engineer an admissions class.

Brian Lehrer: Khalil, thank you for calling up. Keep coming on the show as a caller and we'll have you back as a guest, of course. Thank you very much, and we'll continue with David Leonhardt. There's more to cover here. For example, if working class Americans are more represented by Republicans, why do Republicans continue to take management side over worker side in almost any policy dispute? I'll ask David about that. We'll take more of your calls. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with David Leonhardt from the New York Times, who writes a lot these days about what he calls the Class Inversion of American Politics. That is, Americans with college degrees increasingly likely to vote for Democrats, Americans without college degrees increasingly likely to vote for Republicans.

We'll go to another call in a minute, David, but I know you wrote about how Republicans today are starting to turn away from the core Ronald Reagan era of value of laissez-faire marketplace economics, government not regulating business very much, but this is another area where I'll admit I'm skeptical of the frame that Republicans are becoming the party of the working class because in almost any major policy area don't Republicans favor ownership over labor in their votes consistently against raising the minimum wage, against paid family leave, against tough occupational safety and environmental standards, against Obamacare subsidies for Americans who don't get health insurance through work and the employer tax that goes with it.

They fought to make it harder for unions to collect dues automatically from workers in a union shop. I could go on. Aren't Republicans voting with ownership interests over workers' interests when they're in conflict over and over again?

David: Yes, absolutely. The piece that I wrote was about what is still kind of a fringe movement within the Republican Party, but I think it's a significant one, which is why I wrote about it, which is you start to hear some Republicans say that union membership and collective bargaining is a vital part of our economy. You start to hear some Republicans say that we need to do more to crack down on antitrust, but we're talking about early and small movements. Your list was entirely right. The Republican Party very much still sides with management. The Republican Party's main domestic policy is to try to cut tax rates on rich people. Yes to your entire list.

It is a huge vulnerability for the Republican Party with working class voters. It is an opportunity for Democrats to win those voters. I think what is tricky is those aren't the only issues. What Democrats often try to do is they basically try to say, "Let's please not talk at all about any social issues," on which working class people tend to be quite moderate as we've been talking about, "and let's talk only about economic issues." That isn't persuasive to voters. Voters care deeply about social issues. They care deeply about religion. They care deeply about some of the issues we've been talking about today, like crime, like immigration, like how quickly society should reopen after COVID.

If you doubt that, and if you say, "No, the working class people should just vote their economic interests," I would ask people to flip this on its head and say, "Why is it that the residents to take a New York suburb of Scarsdale, or the residents of Darien, Connecticut have shifted so far to the left?" We now see in high income suburbs and really high income resort places like Martha's Vineyard, we see Democrats win huge victories. The reason is that people in those places are voting against their economic interests. They're voting to raise their own taxes because they care about issues other than economics and working class people feel the same way in many instances.

When they hear progressive talking in ways that doesn't reflect their own values on a long list of issues, they say, "We're not voting for that party even though we disagree with where the Republican Party is on some of these economic issues."

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another call. Mike in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC with David Leonhardt. Hi, Mike.

Mike: Hi. I got to say Mr. Leonhard thas addressed a lot of the points I wanted to bring up, but right now he says, "Why are they voting like this?" Here's the answer, to my mind. The Democratic Party and liberalism and leftism in America started abandoning the working class with the new left in the '60s when [unintelligible 00:34:12] became the dominant issues when they said, "Labor is already an established class, we don't care about them anymore." Let's skip forward. I know I only got a minute. We got Bill Clinton, who was a conservative who disguised himself as a liberal and gave affluent liberals, college educated, graduate degree liberals the disguise to vote as conservatives, to vote their economic interests. They didn't care about union pensions.

Their money was in the market in 401Ks and investments. They didn't care. Bill Clinton, on every single point governed at or to the right of a point Richard Nixon would've governed from. This is inarguably true. Professor, Mr., Dr., whatever, Muhammed made a good point about race. I would disagree with him on one point. I think it's a trick played on us. We all know what Lyndon Johnson said about that. You convince the lowest White man he's better than the best, and I won't go into the language from there. It's trick played on us. Right now, I'm what they call a maintenance engineer. Basically, I polish floors in an office building. It seems to me, and, Brian, I have to say, you keep turning to this and race as the issue.

I feel tricked when I'm supposed to think differently about issues than the guy standing next to me with the same machine named Diaz about issues that affect us. Anyway, I genuinely think American liberalism abandoned the working class starting in the early '60s, coming to fruition massively with Bill Clinton and then Hillary Clinton. This is what they had to offer us. These were people who would've made Richard Nixon proud to govern. All of a sudden, now, people wonder. I'll go to my religious tradition. How come American liberalism can't really engage in, what we call growing up the nuns taught us, the examination of conscience about how we got where we are? That's what I have to say.

Brian Lehrer: That's a lot. We really appreciate your call. You put so much interesting stuff on the table. I'll say one thing on the point on which you referenced me. You and your colleague named Diaz statistically are very likely to vote for different parties for president, just saying. David, Mike also identified himself to our screener as a reader of your columns. Very interesting and very informed take. What do you say listening to Mike?

David: Thank you, Mike. I appreciate that call. I just finished writing a book that'll come out in October called Ours Was the Shining Future: The Rise and Fall of the American Dream. I promise not to give you a book talk in the segment, Brian, but [unintelligible 00:37:19]

Brian Lehrer: By the way, we promised to issue you a formal book invitation. In fact, you can consider this that, but go ahead.

David: Wonderful. I'm very excited to come on the show and talk about it and talk about whatever parts of it you want. Basically, what I try to tell the story of in the book is how American society embraced the interests of working class people and then abandoned those interests. During the mid decades of the 20th century, even as we were a horribly racist and sexist society, the white-Black wage gap shrunk, and the white life expectancy gap shrunk. As bad as things were in many ways during those middle decades, they were also getting better.

What has happened over the last half century is that all these gaps have widened; the economic inequality, racial inequality by wages, by life expectancy, by almost anything. I do think that the move of the Republican Party and conservatism toward a form of laissez-faire capitalism is a central part of that story. Brian, you gave the list before, and the whole move away among Republicans from the approach that Eisenhower and Nixon had toward a kind of compromise between capitalism and between government. Mike's point is also an important part of the story.

The left, starting with the new left and continuing into today, really did stop associating itself with working class people and often show disdain for the views of working class people. I don't think it's surprising, and I say that as someone who has great admiration for the accomplishments of the new left, including the anti-Vietnam War movement, including the environmental movement, but it really is the case that I think that the Democratic Party and progressives should be introspective about why they've lost so many working class voters exactly as Mike says, rather than simply saying the only reason is because those voters are ignorant and the other side plays dirty politics. I don't think it's that simple.

Brian Lehrer: David Leonhardt, from The New York Times for whom the class and version of American politics is a recurring theme. You can see it show up in the Time's, The Morning newsletter which David usually writes, and the Sunday Review section, his other main platform. David, thank you so much for coming on and having this conversation. We always appreciate these.

David: Brian, thanks for the rich conversation and thanks for the tough questions. It makes for much better conversation.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. Brian Lehrer, on WNYC. Much more to come.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.