Tracking Trump's Virus

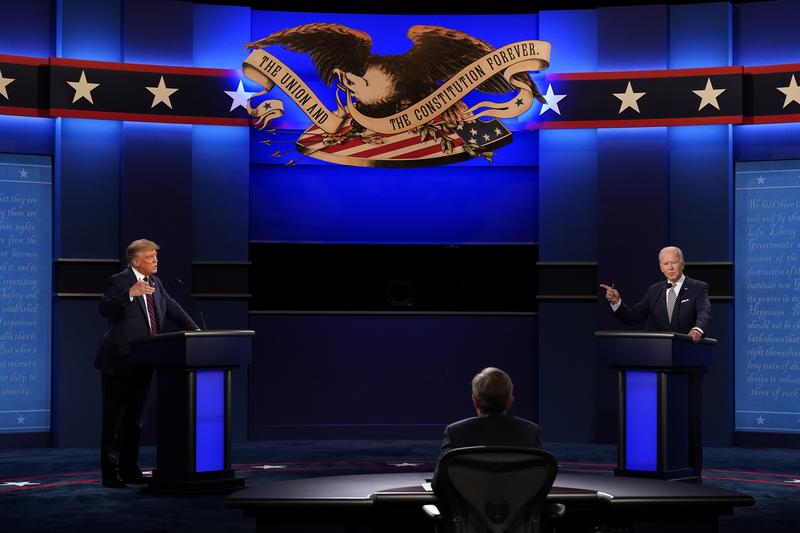

( AP Photo/Patrick Semansky )

[background music]

Male Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

President Donald Trump: I have a mask right here. I put the mask on it when I think I need it. Tonight, as an example, everybody's had a test and you've had social distancing and all of the things that you have to, but I wear masks when needed. When needed, I wear a mask. I don't wear a mask like him. Every time you see me, he's got a mask. He could be speaking 200 feet away from it. He shows up with the biggest mask I've ever seen.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that was President Trump in the debate Tuesday night saying he wears a mask when he feels like he has to and it's needed, but not big, dumb-looking masks like former vice president, Joe Biden, wears. As you all know by now, President Trump has announced in a tweet early this morning that he and his wife, Melania, both tested positive for the coronavirus. He wrote, "We will begin our quarantine and recovery process immediately, we will get through this together." The president's physician, Sean Conley, wrote this morning that Trump and his wife are both well at this time and they plan to remain at home within the White House, during their convalescence.

President said they were quarantined for 14 days, but Trump's schedule over the past week has been packed from rallies in Pennsylvania and Florida and Minnesota to Cleveland for the presidential debate where he shared the stage with former vice president, Joe Biden, who's now getting tested. Who else could the president have infected and what else can we glean about the progression of the disease at this point in him? They acknowledged he is showing symptoms. He's had a hoarse voice, report is also noted that the rally that he gave the other day he was sounding kind of raspy and he cut it much shorter than the usual length of the rallies that he gives.

We have an update just in the last few minutes after a news conference with the White House chief of staff, Mark Meadows. Apparently Meadows confirmed that the White House knew that Trump advisor Hope Hicks had tested positive before Trump left for his New Jersey fundraiser, which was yesterday, and even pulled some staff from that trip, but he went, it's not clear to us at this time with how many people he was in close contact after knowing that he had been exposed to somebody who tested positive.

Let's talk about all of this, and we'll talk about some of that local news too with Dr. Stephen Morse, virologist and epidemiologist at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Dr. Morse, thanks for coming on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Dr. Stephen Morse: Thank you, Brian. It's a pleasure to be back with you even if under these circumstances.

Brian: Indeed. I wonder if you would react first to that latest piece of news from the White House chief of staff. If I'm reading this written report correctly, the White House knew that Hope Hicks, who had been in close contact with the president, had tested positive before the president left for his New Jersey fundraiser yesterday. What, for you as a virologist and epidemiologist, would have been the proper safety protocols at that point and from what you know did the president follow them?

Dr. Morse: I don't know what the president did, but knowing his past behavior I suspect he didn't follow them. One possibility, of course, would have been to do it virtually, the way that he's criticized Joe Biden for doing over Zoom or some other way. Another possibility, obviously, would be to wear a mask, use social distancing, all those other precautions we've heard about, very hard to do on a helicopter or in a conference, but he could have done that certainly in transit, which would have been safer, and in this fundraiser as he did on other occasions.

I think that those precautions we hear about, it's very obvious they really do make a difference. We've seen the proof of that. Also, as you know, today, Ronna McDaniel, the RNC chair just announced that she had tested positive last week.

Brian: Yes. Though I understand that she and the president have not been in close proximity since last Friday. However, she has been campaigning in Michigan, so I don't know who else she has been in close proximity with there. On Instagram we searched the NJ Trump golf club where the event was held yesterday and we saw that some people had posted things like "Absolutely amazing day having my photo taken with president Trump." Then 20 feet from them, I guess there's a characterization here of, he addressed the crowd and took questions, and maybe they were 20 feet from him. If he was talking or talking loudly to people who were sitting 20 feet away, he was affected, would they be at risk?

Dr. Morse: It really depends on the circumstance as the ventilation, how loudly he's talking, how much virus he happens to be producing at that moment. We do say six feet, but that's an average that works for most cases, but there are exceptions. It's really impossible to say, but the end result is that probably there'll be a lot of contact tracing. You can imagine what a herculean task that's going to be with people from so many different places coming together.

Probably the people 20 feet away are at relatively low risk, and usually the recommendations for contact tracing are for people who are in sustained contact for 15 minutes or more at closer than six feet without other protection like masks. That's really generally going to cover most of the people. There may be some exceptions. If they then turn out positive or become sick themselves, there'll be further contact tracing. It's an iterative process that can go on for quite a long time.

Brian: Presumably if there were people getting up close, taking photos with him, they would be at greater risk, though those would have been short contacts as well. How about Joe Biden, who shared the stage, of course, with president Trump on Tuesday? It was indoors. They were distanced a number of feet. If the president was infected already on Tuesday, what would you say Biden's risk is based on those conditions?

Dr. Morse: I think probably it's a low risk, but obviously it's never going to be zero. There's always that possibility, and I'm sure that he's going to be doing regular testing, but it would be ironic actually after all the precautions he's taken, but I think it's not likely, they were at some distance. I noticed that the podiums were also not facing directly. It's probably going to be all right, but you don't know until you see what happens, because this has been very unpredictable in many ways.

Brian: If the president tested positive last night for the first time, and he gets tested every day, and people who come in contact with him get tested before they do so, because he's the president, what's your best educated guess as to when and how he would have been infected?

Dr. Morse: Usually you'd assume someone would come up positive on a task perhaps one day, to a week, probably one, two or three days after being infected. When they start producing virus, it takes at least a day or so. That would probably be about the earliest. It could be as early as the day before, it could have been a few days before. That's always been the problem and trying to figure out how and when people are infected, because there are so many potential exposures that, if someone gets infected within that period of one to three days, they turn positive. You can't be sure exactly when, most people assume it was probably that close contact situation with Hope Hicks.

I know that Annie Karni mentioned that earlier, because she was the most obvious contact, but there could have been others a day earlier as well.

Brian: Listeners, we can take your phone calls on President Trump now having coronavirus for Dr. Stephen Morse, virologist and epidemiologist at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. I'll give you a little behind-the-scenes program shifting around as a result of this story. Dr. Morse was going to come on today to talk about the new study that indicates it's a lot harder to get coronavirus on the subway than a lot of people think it is. We'll do a separate segment on that next week, but somebody is calling with a question about that, and I'm going to take it since this much more directly affects people's lives, at least in the short run, than the president having coronavirus. David in Yonkers, you're on WNYC. Hello.

David: Thank you. When I ride the subway, I have to ride sometimes during rush hour, you can't maintain social distance, it's a packed car, not everyone is wearing a mask, but my question specifically is regarding opening windows on the subway cars. I know there are little signs that say, "Please close the windows," but that, they have that put there a long time ago before the coronavirus. Is it better to open the windows on the subway cars or to leave them closed in terms of the virus?

Dr. Morse: That's a great question. My understanding, actually, is that there is something like 18 air changes an hour in the subway, so that in each subway car, so that there's a lot of airflow, and it probably would really provide a lot of ventilation.

That's probably one of the reasons that we have not seen cases that could really be traced back to the subways, despite the fact that it's difficult to socially distance and do all of the things we'd like to do, and we were concerned about the subway. I think that there's already plenty of ventilation in the car. It's more than in most offices, more than in most inside spaces.

Brian: I know you read closely, on our behalf, the study over the last 24 hours. Again, we will spend more time taking a closer look at this next week, but if there is a low infection rate in the city, that's one thing. If we were to get to a point like we were in the spring where there was very high infection rate, and we're starting to get higher in some neighborhoods as you know, then maybe that's the only time you could really scientifically measure the transmission rate in the subways because it's different if there isn't a lot of virus in the environment.

Dr. Morse: Yes. I think that's absolutely right, but also, it's really very hard to determine in many cases when someone who's out in the world and has had many potential exposures, many places where they might have gotten exposed, just like President Trump, where they actually got infected. You really are working a lot with correlations, with going back to contact tracing and seeing if any of them can be traced back directly in numbers to subway rides.

There was a paper published a while back that suggested that the city's subway system was actually one of the vehicles that, pardon the pun, for spreading the virus, and I think a lot of us felt that this was methodologically flawed. I think this new study from Sam Schwartz is really much more definitive, in that it's hard to get an absolute answer, but it really shows that we can't attribute or find any cases related to riding the subways, and there is not a close correlation between what's going on in the outside world and those who are riding the subways.

There are a lot of people riding the subways, even when there was a high level in the city, but also when there was a low level and when there was a high level, there were fewer people riding the subways, but still a lot of virus circulation. I think that indicates the subways are a lot safer than we had thought originally.

Brian: Senator Mike Lee, Republican of Utah, has tested positive, and he's a member of the Judiciary Committee, and reporters are tweeting photos of him from the other day with Amy Coney Barrett, unmasked indoors, and so there's the chain of infection that goes on and on until it doesn't. Right, Dr. Morse?

Dr. Morse: Yes, exactly. I know earlier reports had said that she had tested negative, but of course, you can be negative today and just incubating the virus and then be positive the next day, so I think that is obviously a concern. The effect and how this is going to play out, I think is going to be quite interesting. It feels sometimes like we're all living in some strange dystopian novel.

Brian: Mary in Fairfield County, you're on WNYC. Hi, Mary.

Mary: Hi, Brian. I would like to ask the doctor, given what he's talking about with the variability of the latency period of incubation, it sounds as if the president could have infected Hope Hicks, rather than vice versa. Would that be possible?

Dr. Morse: It is possible. It hasn't been completely traced back, and there were so many other people in the president's circle who have been infected at various times, I think. It was actually quite surprising that he never did seem to get infected, which says something, but it is possible. I think we would have to work out the timelines very carefully to try to understand exactly what the timing was and what the possible exposures were, and that's probably better done later on rather than in the heat of the moment.

Brian: James in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, James.

James: Hello.

Brian: Hi, James.

James: Yes. Hello.

Dr. Morse: Hello.

James: Am I there?

Brian: Yes, you're on. You're on the air.

James: Okay. I just wanted to raise the issue of the president's absolute failure on this transmission thing by refusing to enforce a mask policy. This is the clearest demonstration you could have of the effectiveness or the non-effectiveness of whether you do or don't use the mask policy. The truth is, if they had had the mask policy, people would have gotten infected, but it would have been stopped cold and it wouldn't be the way it's spreading now at the White House.

The other thick, main point is that if the president is coming through with a mild case like Bolsonaro or Boris Johnson, and if he intends to crow about it, I think we need to be aware of the fact that we don't understand how the virus works. We don't know why it's mild in some people and different in others and fatal. We do know one thing about the fatality rate. Don't we, doctor? That the fatality rate is largely dependent on access to medical care, because in February, when the president told Woodward that he knew that 5% of people who got it would be dead, that was based on misunderstanding and not really knowing that, that's only true if nobody has access to medical care, but--

Brian: I'm going to leave it there, James. You put a lot on the table. Doctor?

Dr. Morse: We have gotten better at treating these severe cases that has reduced the case fatality ratio for those who are hospitalized, but on the other hand, that's not the outcome I'd like to see. I would much rather see these cases prevented rather than see people get sick. Then, as in Boris Johnson's case, it can start out very mildly and then rapidly progressed as it did there. We don't know what's going to happen with the president. Right now it's mild, but it could change at any minute.

Yes, the case fatality ratio is largely dependent on quality of care, but really the best thing to do is to prevent getting infected in the first place. That's where the masks, the social distancing, the hand hygiene, all those other precautions are really very useful and really make a difference.

Brian: That's where we will leave it with Dr. Stephen Morse, virologist and epidemiologist at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Thank you so much.

Dr. Morse: Thank you very much.

Brian: The Brian Lehrer Show is produced by Lisa Allison, Mary Croke, Zoe Azulay, Amina Srna, and Carl Boisrond. Zach Gottehrer-Cohen works on our daily podcast. Our interns are Daniel Girma and Erica Scalise. This fall, Megan Ryan is the head of Live Radio. That's Juliana Fonda at the audio controls telling me "You're not on the air, you're not on the air. Press the other switch," along with Liora Noam-Kravitz, Matt Marando and Milton Ruiz at another time. Have a great weekend. I'm Brian Lehrer.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.