'Soil': Gardening, Community, Motherhood and Labor

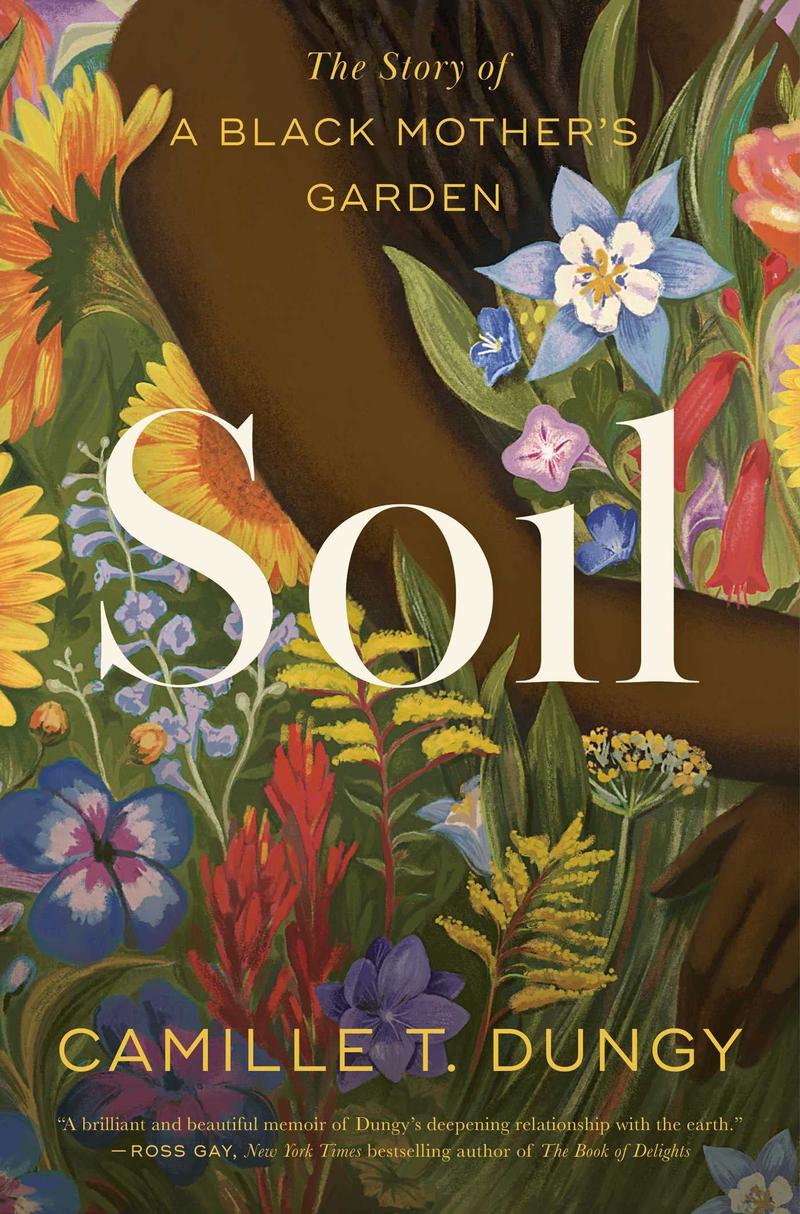

( Camille T. Dungy / Simon and Shuster )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. The poet Camille Dungy moved with her family from Oakland, California, to the predominantly white Fort Collins, Colorado for a faculty position at Colorado State University. When the family moved into a house, Dungy imaged what her lawn could be. Not a freshly manicured mark of suburban homogeneous lawn culture, like we might imagine it, but into a site of possibility, community, love.

Camille Dungy's memoir, Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden, documents the seven-year period that she and her family spent working toward that. We'll end the show today by talking about what she learned from this project, how this book should expand the way we talk about wilderness and the natural world, and who we imagine is capable of telling these stories. Camille Dungy, thank you for your book and for being with us today. Welcome to WNYC.

Camille Dungy: Thank you very much. I'm really happy to be here.

Brian Lehrer: Take us to Fort Collins, Colorado. How would you describe it for those unfamiliar, and do you want to do it in sort of horticultural terms?

Camille Dungy: [laughs] Fort Collins, Colorado is in northern Colorado. It's at the same latitude as New York City, interestingly, but a mile higher, so we're about 5,000 feet elevation, and so it stays cooler longer, and gets cooler sooner than it might in New York. It is a Western grassland prairie, the part of Colorado where I live predominantly, so the native landscape would mostly be grasses and sage grass with a few kind of short, shrubby bushes here and there, and an occasional conifer, kind of dry desert climate.

Brian Lehrer: What did you want to grow, and what reactions were you met with?

Camille Dungy: I had, when we moved into the house, it was a lawn that was maintained with a lot of water and herbicides and pesticides, and some other really very highly manicured, fairly monochromatic plantings. I wanted something much more raucous and wild, and also native. We eventually took one whole section of the lawn out, and then other plots throughout, and replaced those areas with native plants and pollinator-friendly plants that flower throughout the growing season in lots of different ways.

Brian Lehrer: You met resistance, like a woman in your neighborhood promoting, through a homeowner's association, a yard maintenance code, as you write, a culture that, through laws and customs that amount to toxic actions and culturally constructed weeding, effectively maintain maintains homogeneous spaces around American homes. Can you talk about the consequences of that American monoculture and how you imagined you could counter it through your own yard and garden, and this book?

Camille Dungy: Right. It's important not to forget the legacy of redlining and other kinds of racialized, discriminatory, segregation practices in most American suburbs. That meant that only certain kinds of people were meant to be living in those places. The offshoot, I guess, of that, that then also says that your yard is only supposed to look a certain kind of way, is part of a limiting mindset and imagination of what things and people and lives should look like and how they should behave.

When I, as the only Black family in this community, moved in, we brought that difference with us to this place, and then I'm asking to change ideas about not just what the inside of our house looked like, but what the outside of our house looked like, these things are connected. The removal of native landscapes, the refusal of a diversity of possibilities so that a yard in New England or New York or Minnesota is supposed to look the same as a yard in Colorado or California, where all of those climates are different, all the requirements are different, that feels to me to be dangerous and also part of a continuation of a systemic violence that homogenous thinking continues to support. Our family decided that that wasn't going to be something that we were going to participate in.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take a few phone calls for Camille Dungy, poet, professor at Colorado State, whose memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden is just out and recounts the seven years she and her family spent rewilding her yard and cultivating a diverse garden in her home or outside her home in Fort Collins, Colorado. It also addresses race, history, the predominantly white genre of nature writing, and sustainability. Who has a story like this? Anybody else, or any question that you want to ask Camille? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

Since you are here on the occasion of the publication of this book, it is part of your critique that the genre itself, nature writing, has had white men as the main people who've been celebrated. Do you want to talk about that, and what you think it has, in a kind of literary context, given people the impression of, with respect to nature?

Camille Dungy: The American 19th and 20th century ideas of nature writing, very, very frequently, one person, and usually a man, and almost always white, going away from home in order to have some kind of engagement with the greater than human world that would help that individual become a better person and understanding the world. Often, the families that these men had are erased from the text and we don't really know them in that kind of community.

What that meant is women, people who are responsible for childcare or elder care, or just interested in living in community, weren't really seen in the canonical environmental texts. There's a disengagement from social concerns and economic concerns and the realities of life of most people. I was writing this book during 2020 when I was home overseeing the remote education of my daughter. Even if I had wanted to have some sort of disconnected time in some supposed sublime environment, I couldn't have.

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Camille Dungy: I then began to really interrogate what the dangers are of thinking that the wild and the important world that's worth preserving has to somehow be separate from us. Who then thinks that they aren't responsible for nature, aren't responsible for caring about or loving or shaping their environment in a way that is supportive, because nature always seems to be someplace where people are erased.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a caller who-- I don't know how close she is to Fort Collins, but she's in Colorado. Susanna in-- is it Erie, Colorado? Susanna, hi, you're on WNYC.

Camille Dungy: Yes, you're just up the road. Hi there.

Susanna: Yes, totally. I grew up in New York City, but I grew up in the Projects. Now I'm in Colorado where I have a lawn. We're actually the newer development, so we had to get a lawn put in, and I'm like, I don't really want a lawn because it's not the climate to maintain a lawn and our water bill is ridiculous. I was wondering, because I went to your website and found your book on Old Firehouse Books and wanted to know if the book offers tips and tricks on how to maybe convert from what was mandated by the builders to maybe something more native to Colorado.

Camille Dungy: I have been lucky, actually, in Fort Collins. The city itself has got these really active initiatives to support homeowners in moving

towards Xeriscaping projects and low water use and native plants. Unlike many people across the country, my slow efforts-- because I did most of the work myself, they ended up being relatively slow efforts-- caught up to the city, or the city caught up to my efforts, so I have been blessed.

My advice for you in Erie, Colorado is to maybe look into buffalo grass and blue grama, which can be planted as turf and are native and will eventually use less water. In the book, I do talk about the process I went through and the choices I went through to make the decisions that I made in the yard, but I think each community and each climate zone is a little bit different. I wanted to give space for people to understand how to work with their own kind of--

Brian Lehrer: Microecosystem, right?

Camille Dungy: Correct.

Brian Lehrer: Susanna, thank you for your call. I hope that was at least somewhat useful to you there in Erie, Colorado. Tiffany in Washington Heights, also with a connection to Fort Collins, you're on WNYC. Hi, Tiffany.

Tiffany: Hey, Brian. Big fan, multiple-time caller. I have not read your guest's book. I'm from Loveland, Colorado, right next to Fort Collins, so obviously, I spent most of my growing-up years in the college town next door. Just want to mention, too, it's right next to the mountains. A lot of people, when you describe it being very dry and grassy, might think you're in eastern Colorado, but right next to the mountain. I had a question really quick. I don't know if you can even divulge, but can you tell me where your home is in Fort Collins? Is it by chance on Mountain Avenue?

Brian Lehrer: Oh, boy.

Camille Dungy: It is not on Mountain Avenue. I think that the thing about Fort Collins being close to the mountains is really something I'd like to chat about a little bit, because it's a place, it's beautiful. If you turn towards the west, there's the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains just right there. You can bike into the foothills in 15 minutes. That incredible, grand, sublime landscape is right there. Also behind you are these prairies and feedlots and a different kind of space.

For me living in that area, I've become really aware of this fabrication, almost, of what makes the sublime landscape, because I only entirely get that if I look in just one direction. If I look in a 360 direction, I see all different kinds of manifestations of the natural world and the human world. To me, that becomes really interesting.

Brian Lehrer: [crosstalk] Let me jump in and ask you.

Camille Dungy: If it's okay, caller, I don't really want to say exactly where I live.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. No, good idea. Tiffany, thank you. We've got about 45 seconds left. Can you give us a quick thought on this one thing in the book? You're right, every politically engaged person should have a garden. That even made some of us think about the killing of Ralph Yarl, shot simply for ringing the wrong doorbell, or pulling into the wrong driveway, Kaylin Gillis and Ralph Yarl. I'm just curious how you imagine your garden as a means to politically cultivating community. We have 20 seconds.

Camille Dungy: Oh, my goodness.

Brian Lehrer: Shot, not killed, I should say, in the case of Yarl.

Camille Dungy: Because as a Black person in this country, I need a space of beauty and respite and care, and the garden gives me that. I also need a space where I can see that the care and the work and the effort that I put into making something more beautiful and sustainable can pay off, because stories like the ones that you're describing, which happen over and over again, are horrific and exhausting. The garden gives me a space to counter that horror.

Brian Lehrer: That has to be the last word from Camille Dungy, whose book is called Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. Let me say that on Thursday at 7:00 PM Camille has an event that's part of the PEN World Voices Festival. It's taking place in LA, but we figured we'd mentioned it for any of our LA-based listeners. It's at the California African American Museum and it's free, May 11th, Thursday, 7:00 PM. Thank you so much, Camille.

Camille Dungy: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.