A School Psychologist Shares How to Guide Students -- and Teachers -- Through Trauma

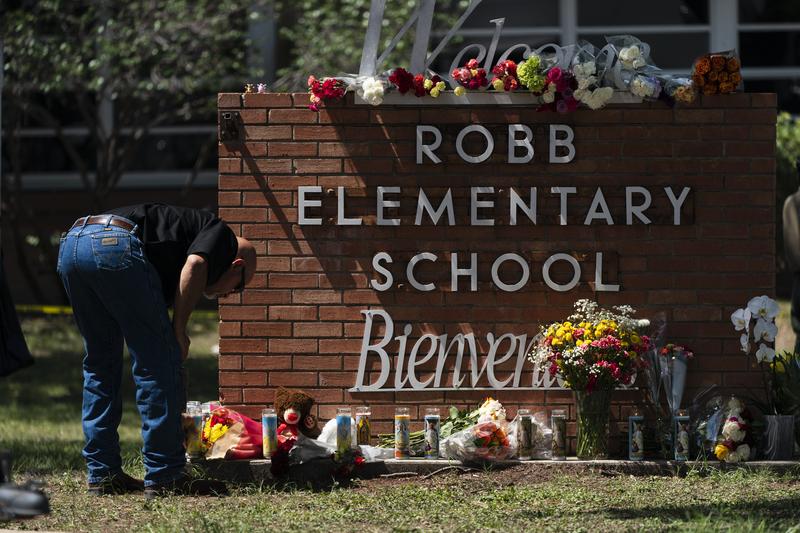

( AP Photo/Jae C. Hong / Associated Press )

[music]

Brigid Bergin: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Brigid Bergin from the WNYC and Gothamist newsroom, filling in for Brian today. 10 years ago in the aftermath of the horrific mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, I was in Newtown, Connecticut reporting for WNYC and NPR. I met a high school social studies teacher who lived in the community. He told me about his experience in his classroom in nearby Fairfield, Connecticut the day of the shooting, learning about the events as they were unfolding that Friday, and how he planned to talk with his students when they all returned to class on Monday. He knew they would have questions.

Teachers and other school staff members, we are so grateful to you for all you do and all that you've gone through. We just want to acknowledge that this is hard for you too because here we are again with children, parents, and teachers grappling with how to talk about the latest mass shooting. This time at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, and less than two weeks after another mass shooting closer to home in Buffalo.

Joining me now to offer some guidance on how to have those tough conversations is Dr. Christina Chester, a school psychologist who works with the National Association of School Psychologists on school crisis prevention and response. She works in the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland, the 15th largest school district in the nation. Dr. Chester, welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Chester: Thank you for having me.

Brigid Bergin: Listeners, we want to know what kind of conversations are you having with the children in your life about these latest events? Have you talked about the mass shooting in Buffalo, only to have to have another conversation 10 days later about Uvalde, Texas? Are your kids asking questions about what happened, and how are you deciding what and how much to tell them?

If there happened to be any teachers who are out there who can speak to what their classroom was like yesterday, or maybe if you're listening on your break today, let us know. Or do you have a question for Dr. Chester about how to talk about these issues? Call us at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer.

Dr. Chester, as a school psychologist, after a traumatic event like the one in Uvalde or in Buffalo, how does it change the school environment, even for those geographically removed from the events, particularly for the kids?

Dr. Chester: Well, events like this can definitely have a psychological impact on our students and our staff, as you so eloquently mentioned earlier. They start to question are schools safe? Is my work environment safe? Is this going to happen to me? There can be lots of anxiety and fear when they hear about things like this. As we were talking about, one of the things is we want to make sure that for the listeners and our families and our staff members out there, trying to make sure to reassure our students that schools are safe, that they are safe. Also, validate their feelings around what's going on and try to talk with them around what they are experiencing at that moment.

Brigid Bergin: We're still very much in the early days after this mass-casualty event. Now beyond the scale of the tragedy, we're starting to see the faces of the kids and the teachers who were killed. It's hard to see. What kind of guidance do you offer to parents and teachers for how to communicate to kids now at this stage in the immediate aftermath?

Dr. Chester: Try to help students to know that we live in this age where they have access to the news, to media 24 hours a day, and that they can go on social media, traditional media. Even this morning I was looking at the pictures that were posted about the staff and the students there who were killed in Uvalde, and it's emotional. What can we do to help our kids to know that you may not want to look at these pictures? You may not want to go on and read about these events, because we know that it does have an emotional impact on them. For those who have recently experienced other types of traumatic events, it can retrigger them.

For our families, if you're watching the news and you have young children who are there with you, you may not want to watch the news at that moment. Now, is it possible to DVR it or watch it on YouTube or another platform later once they've gone to bed? We know that the adults want to know what's going on, but it might not be the best time at this moment to watch it with your children.

Brigid Bergin: In these past few days we've seen, I think, a lot written about how to talk to children about mass shootings. As an expert, I'm hoping you could walk us through some pointers. First, in terms of how do you adjust what you say based on the children's age or grade level? I've read some experts say that if a child, for example, is under eight years old and is unlikely to hear about this from someone else, then perhaps you don't need to talk about it at all. What's your perspective on that?

Dr. Chester: No, that's very true. For students who are listening, like an early elementary school, like you said, eight years old or third grade or younger, if they don't know about it it's okay not to share. It's okay for them to be naive around what's going on in the world and let them continue to be in their childhood lives and not have to know about such horrific things. If they do become aware of it, let's say if kids are talking about it in the playground or at lunch or they hear about these things, making sure that our explanations are brief, they have a good balance of reassurances that their school, their homes are safe, and the adults are there to protect them.

Also, give them examples of what their schools are doing in order to maintain safety there as well. Even reminding them about the lockdown drills that they do in school that are required. Then for the older kids, there you're going to have a different type of conversation with them.

Brigid Bergin: How do you start that conversation? Particularly since I've read if you focus the conversation on feelings, that might be one of the ways that you could shut down an older child who you're talking to about this kind of incident.

Dr. Chester: Well, older kids they're going to be more vocal about what they've heard, how they're feeling, and what is going to be done about it, especially as you get the kids who are in middle school and high school who are starting to have those conversations around civics, around politics, so forth. They may be very vocal about how they feel and what should happen. It's okay to make that time to talk to them. Have those conversations. Hear what they have to say. Hear what their friends are saying or what their friends in school and online are sharing around what's going on.

Again with them, you're still going to reassure that schools are safe, and especially for some of the kids, let's say, fourth, fifth, sixth grade. Going in and just trying to make sure that we are differentiating what's the reality versus fantasies or exaggerations about what actually occurred. Kids that are in high school, older kids like seventh, eighth grade, and middle school, what are the roles that they, the students, can play in order to maintain safety in their schools? Let's say if they hear about a threat on social media. How can they share that information?

Because we know that in many of these situations, people do make these threats on social media before they go forth and carry this out. What is their role in order to maintain the safety in their schools and at home?

Brigid Bergin: This sort of gets back to, I think, part of what you were talking about before, and one of the recommendations from your organization, which is to reaffirm the safety in school. I'm wondering to what extent, how do you balance that guidance with the reality that you can't guarantee that nothing bad will ever happen again?

Dr. Chester: Right. Like you say, we can't say, "Oh, this will never happen here" because we can't guarantee that. That's not a guarantee in life that any of us can make. All we can do is say these are the things that we're doing to maintain the safety at home and at school. We do drills. We make sure that the doors are locked. We don't let strangers into the building. All the things that they can do, we are doing as the adults in order to maintain the safety that's there. Just constantly reassuring them about the concepts around like those physical safety concepts, but also the psychological safety concepts.

I notice a lot of conversations around mental health. What are we doing to provide mental health support for students in our schools? If you know of somebody who's having concerns, how do you report it? Do you have a tipline in your school system that shares about information, or that people can anonymously report things if they're concerned about being thought of as a tattletale? What are specific things that are happening in your community that help all of our students and our staff members maintain safety there?

Brigid Bergin: You're listening to The Brian Lehrer Show. I'm Brigid Bergin filling in for Brian today. I'm speaking with Dr. Christina Chester, a school psychologist from Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland, on how to talk to kids and support educators when it comes to the events we saw in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo. We invite you to join this conversation. What kind of conversations are you having with the children in your life about the latest events? Or do you have a question for Dr. Chester about how to talk about these issues? Call us at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer.

Dr. Chester, in the shooting in Texas many of the people who were killed were Latino, and Buffalo, the killer targeted Black victims in a racist attack. How do you help children and families process that additional trauma when they identify with the victims? When they see something like this targeting their community and they're trying to understand why these individuals were targeted?

Dr. Chester: Oh, absolutely, and that's an excellent question because we understand that incidents of racism by itself is highly traumatic on individuals of color and other marginalized communities. Especially for the community in Buffalo, when they see that another community of color in Texas has now been a target of a mass casualty event, that can just retrigger everything that just occurred to them. Especially for communities of color and for other individuals who are allies and support communities of color and staff and students of color in their schools and workplaces and so forth, it's something to be aware of.

That this could have an additional triggering response on them because of what just occurred. Here is another community of color that has been a target of mass violence here in our country. That is something that we have to pay particularly close attention to. Making sure that they are okay because there's a strong possibility at this moment they may not be, and that this may have an additional traumatic response for them.

Brigid Bergin: Keeping that in mind as parents and teachers are trying to process these events themselves and help the children in their lives process them, what kind of signs and behaviors should they be alert to when monitoring the emotional state of the child?

Dr. Chester: Again, not all kids can express their feelings verbally, so you may see changes in their behavior. Maybe if they're a kid who's normally really positive and easygoing, and all of a sudden they have a change of behavior where they're feeling really negative or they're angry or they're withdrawn, not paying attention. At home maybe they're having trouble sleeping or they're having nightmares. They may have trouble eating. Maybe they're coming up to you and they're even more clingy than what they normally may be.

If they're really young you might see some developmental milestones that might not be happening now like potty training or maybe they're wetting to bed at night. Just looking for changes in their normal behavior. That's an indication that even though they may not be able to express that "I'm feeling this way," it may show that something is going on and that I am having a reaction to the events in my environment.

Brigid Bergin: Let's go to one of our callers. Lisa in Forest Hills, welcome to WNYC.

Lisa: Hi, Brigid. Thank you so much for taking my call, and thank you for having this guest, Dr. Chester, bring up so many good points really. I wish everybody could hear this. I'm 56, and when I was a school-age person I wouldn't see stuff like this all over the media because it was a different world. I'm curious. I mean, I understand that we want to get the information out there, and there's almost no way to avoid seeing it. This is maybe too idealistic of a point, but people like you, Dr. Chester, is there a way to impress upon the media to find a balance of how much of this-- in effect advertise this kind of thing? If you know what I'm saying.

Like I said, maybe this is too idealistic of a point but I'm just curious if you have any thoughts on that or if there's any talk in your community as a doctor about that.

Brigid Bergin: Thanks, Lisa, for that question. Dr. Chester, I was looking at some of the guidance that NASP, your organization, puts out, and there are some very specific suggestions to schools about how to manage the media. That's one side of the equation that Lisa's talking about, but then of course the other side of it is the proliferation of all this information. Maybe you can speak to both of those points.

Dr. Chester: Oh yes. Organizations like mine, mental health organizations around the country, we do try to work with our media partners around how this information is brought forth to the public and trying to give them best practices for reporting. I know we've done really excellent jobs especially when it comes to issues around death by suicide, and there's been a lot of changes in how that information gets reported over the past decade. When it comes to events like this and they become what's called newsworthy, then it's like you're in this 24-hour news cycle and everybody is reporting it and everybody then goes online.

You have the traditional media who follows one set of rules, but then you also have people online who aren't part of those normal processes, and they do whatever they want. It's hard. What we try to do is try to talk to the consumer and say we know that all this is out there, and it's really hard trying to find that balance between what information must go out so people are aware, and then you don't get inundated with it so much that it starts to-- what we call vicarious trauma by watching so much media around the situation.

That's why we really try and encourage folks to limit the amount of television or social media or other means like watching videos online about the incident because we know that it can have a negative impact on people. It does come to a place where we try to balance talking to our media partners around some of this, but then also talking to the consumers of that media to say, "Hey, it's one thing to watch it for a day but you may not want to watch it every day, all day because it may have a negative impact on you."

Brigid Bergin: Thank you so much for that Dr. Chester. I have to do a station ID so pardon me for one moment. I'm Brigid Bergin from the WNYC and Gothamist newsroom filling in for Brian Lehrer. This is WNYC-FM, HD, and AM, New York; WNJT-FM 88.1, Trenton; WNJP 88.5, Sussex; WNJY 89.3, Netcong; and WNJO 90.3, Toms River. This is New York and New Jersey Public Radio, and we're talking with Dr. Christina Chester, a school psychologist with the National Association of School Psychologists. She works in the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland talking about how to talk to kids about trauma, particularly in the wake of these recent mass shootings.

Let's go to Jessie in Park Slope. Jessie, welcome to WNYC.

Jessie: Hi. Thanks so much for having me, and really thanks so much for having this conversation. It's someone that so many parents need to hear right now.

Brigid Bergin: Do you have a question for Dr. Chester or have you had a conversation with your children?

Jessie: Yes. I am struggling with that conversation now. I have two children in elementary school in Park Slope, Gowanus. They've actually had two active shooter scenarios just during COVID alone. I'm trying to figure out how to reassure them that they're safe in school when there have actually been shooters around their school building. They've been in lockdown for a full day twice now just during an already anxious time during COVID.

Brigid Bergin: Jessie, I'm so sorry to hear that. Were those false alarms or were they actual incidents? Do you know?

Jessie: No. Unfortunately, they were actual incidences. The subway shooting was two stops down from their school. Then there was another incident where someone had a gun in the area. As well as doing drills, and they've also had to do an evacuation. They've had a lot of exposure to this and I'm just trying to figure out-- Both my second and fourth graders want to know if people are getting close to school with guns, what's to say they're not going to then be in school? I'm just struggling for something that will reassure them.

Brigid Bergin: Dr. Chester, do you have any advice for Jessie?

Dr. Chester: No, and again I'm sorry to hear about these incidents that have occurred within close proximity to your kids' schools. I understand just how scary that may be for kids especially. Then you see this going on and then it reminds them of these instances that have occurred during this period of time. Just remind them about what are the things that were done in order to maintain their safety in the school? When they went on lockdown, what are the procedures that they followed? How did the school work with the local law enforcement around making sure that individuals who are in the community didn't come onto school grounds, and what they did in order to maintain the safety in the schools? While sitting there and being fearful about this and saying like, "Oh my goodness. This happened really close and it could have happened to us. What if this has come onto our campus?" can definitely ring in the minds of the students and the staff in the school.

Just trying to remind them that you are safe, there were procedures that were put in place, and just constantly reassure them that these are the things that are happening. You are safe, this didn't occur here, and that the school will continue to put things in place and look at things and look at the safety procedures in order to make sure that all the students in the school remain safe.

Brigid Bergin: Thank you, Dr. Chester. Jessie-- Oh. I'm sorry we cut Jessie out there. Sorry, Jessie. What was your follow-up?

Jessie: I just wanted to say that at the time that we had each of these incidences the school did a wonderful job making the kids feel safe because they had drills. They weren't anxious at those times. It was purely with this actual shooting of children their age that the extra anxiety came up. Thank you so much for that advice.

Brigid Bergin: Jessie, thanks so much for calling in. Thanks for letting us know that there was some reassurance that came with-- In addition to the trauma that your kids went through, that they did get a sense that the school had things under control. I think that's important for our listeners to know.

Let's go to Sarah in Brooklyn. Sarah, what's your question or comment for Dr. Chester?

Sarah: Hi. My seven-year-old, she's in second grade. When she learned about the shooting in Uvalde, she had this lighthearted curiosity, I would say, about it. She was very curious about the specifics of where was the classroom located in the school? How many teachers were in the class? How many students were in the class? Was it multiple classrooms? Were there windows? I'm curious about how to understand what's going on with that level of curiosity and whether or not-- How to direct the conversation and how frank to be with her about details.

Brigid Bergin: Sarah, thank you for that question. Dr. Chester, kids and their curiosities are things I think we as parents are often [chuckles] confounded by. Do you have any advice for how to answer these types of questions?

Dr. Chester: Yes. Kids are very curious. I have a 12-year-old myself who asks lots of questions when these incidents are occurring around the country and in our community too. I would say, especially for younger kids, it's okay to not give them some of the details that they want to know because some of it is curiosity. Some of it you may not know at the time. Especially if they ask early on, a lot of those details weren't available. They were still conducting their investigation.

Now we know the shooting happened in one classroom. It's okay to say, "Oh, I don't know. The police are still looking at it. They're still doing their investigation." Especially at that age, when going in and doing crisis response in elementary schools, I would say that my second, third-grade classrooms probably give me the most questions around what's happened. They have lots of-- and they feed off each other.

What can we do in order to be able to answer them as briefly as possible but without giving too much details that may be scary or may cause them to have bad dreams or other negative feelings around what's occurred because they are curious? It's okay to say that you don't know. If it's something that you feel might scare them, it's okay not to share it with them. Just because they ask doesn't mean at that time, especially at that age level, that they really have a need to know.

Brigid Bergin: Sarah, I hope that helps. I have a curious young one too who can ask a whole list of questions, and it can be challenging to figure out how much and what exactly to say in those responses. Thank you for your call and thank you for your question. Dr. Chester, the National Association of School Psychologists lays out a pretty long timeline for how schools can recover from tragedies like this one. We know that the conversations teachers, students, and parents have today and this week are going to change over time. What are some things that can help kids, and frankly the educators in the building regain a sense of normalcy, and how much time does that take?

Dr. Chester: For some, depending on the incident, it can take months, others it can take years. Unfortunately with these incidents, they're at the beginning of recovery. They're in right now what we call short-term recovery, and it will continue into long-term recovery over some time. There will be incidents that occur, let's say, like the anniversary of the event in the year that will come about and retrigger feelings and emotions about what's happened.

We try to tell folks, "Try to maintain a sense of normalcy in your normal routine as much as possible," and we know it's hard. Because right now they're going into the summer, but what can the schools do in order to try to maintain a sense of community, for students and staff to be able to continue to come together, talk to each other around what's going on. Having events that helps to bring them together that are intentional to allow them opportunities to bond.

The community will come together and bring lots of resources and help. There'll be tons of volunteers from all over that community that's going to come in and want to do things for them. As you're going through and trying to figure out all these things and what resources we need and support that's there, but eventually as you go on like three, four months from now those things may go away.

What can a community still do in order to maintain a sense that they're united to continue to build upon resiliency from what's happened? The community coming together to figure out what are the things that need? What are the things that can continue in order to rebuild trust, rebuild a sense of safety for the staff and students of that school and that community? To help them to make sense of what's happened, and to help them to stay together and be united through this horrific time.

Brigid Bergin: We're going to have to leave it there for now. Thank you, Dr. Christina Chester, a school psychologist with the National Association of School Psychologists who works on Crisis Prevention and Response. She's from the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland. Thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Chester: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.