Revisiting Los Angeles 1992 with Anna Deavere Smith

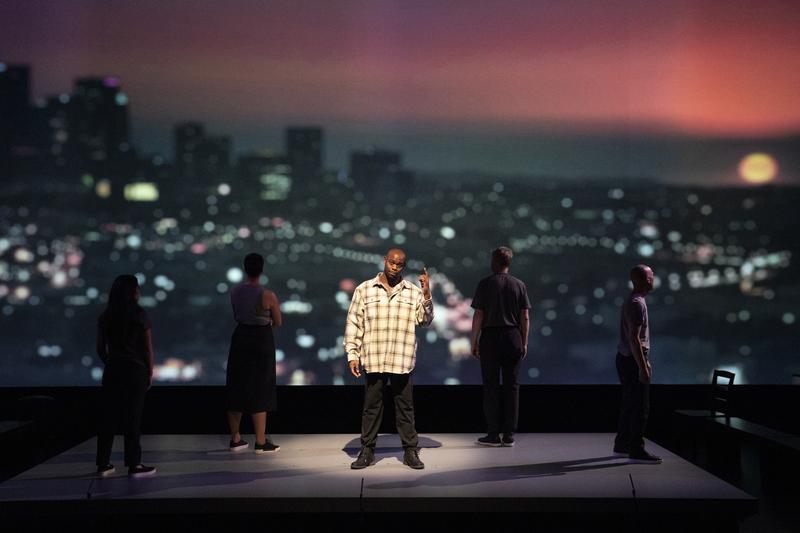

( Joan Marcus / Signature Theatre )

[music]

[crowd chanting]

Brian Lehrer: A crowd chants "No justice, no peace" in protest of the treatment of a Black man by the police. When and where we can't tell, can we? As it happens, this was May 2020 in Brooklyn, one of the many protests around the country after the murder of George Floyd. That it could have been recorded so many other places and times is one of the reasons for the revival of Anna Deavere Smith's play Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, about the causes and effects of the five days of fires, looting, and violence that erupted in LA after the police officers charged in the beating of Rodney King were acquitted. Violence that left over 50 people dead, buildings destroyed, thousands injured and thousands more arrested.

The play is based on over 300 interviews that Anna Deavere Smith did with people from all across racial and class lines in LA, and was first staged in 1993, right after the federal trial finally brought some justice to Rodney King with a conviction of two of the LAPD officers for violating his civil rights. The piece was originally staged as a one-woman play, as many of you who've seen Anna Deavere Smith perform know, with her herself. The new staging has a cast of five actors plus a new chapter, and it's on stage at the Signature Theater through November 21st. Anna Deavere Smith joins me now. So great to have you back on the show. Welcome back to WNYC.

Anna Deavere Smith: So great to be with you. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: This is new, having a cast of other actors perform your work. You're best known for the one-woman presentations. Why this way now?

Anna Deavere Smith: Well, the original idea was to have a company of actors who told stories of America in times of conflict from multiple points of view. The first one of these I made had 20 actors and 20 real people. I'm really going back to the original idea of what I had wanted this project to be.

Brian Lehrer: For people who've been following your work since what might feel like the beginning here in New York, your solo approach started with the play Fires in the Mirror based on interviews you did following the Crown Heights riots here in New York in the early '90s. What more did you want to get at with what happened in Los Angeles that took you there? Maybe you can talk about some of the similarities and some of the differences between the two cases.

Anna Deavere Smith: Yes, sure. Well, let me say, first of all, that I was invited to be one of the playwrights in residence at Signature Theater that has a fantastic playwright residency program. It's a theater dedicated to playwrights. I guess three years ago, Paige Evans asked if I would like to be a resident playwright, which meant that they would, as they do with Signature, take two plays that had been done before. One was Fires in the Mirror, one was Twilight. That was already set up.

Then of course, with the pandemic, Twilight was delayed. It should have been on stage last year; it was late twice. Unfortunately in that time, it became more relevant because of the murder of George Floyd and the uprisings that followed it, and the kind of renewal to a movement that has been certainly going on particularly in the 2000s. Unfortunately, the play is even more timely than we expected it to be when I agreed to have Signature include it in its season.

Brian Lehrer: Right. I guess one of the oddities of the pandemic is that Signature Theater Company, which as you describe, focuses on the works of one or more playwrights in a typical season. The pandemic interrupted your season. They had already staged Fires in the Mirror with one actor, not you, playing all the parts. Then boom, the pandemic, and in the middle of that the police murder of George Floyd, and here you were even more relevant than before.

Anna Deavere Smith: Correct, yes. Look, I've learned-- because my work has always been dedicated in part to race relations, or at the very least how race manifests in America. We have very brief windows, and I'm sure you know this as a journalist too, in which there's an appetite to really discuss race and the adjacent problems that come with it: criminal justice, equity in schools, equity in courtrooms, policing, the wealth gap, and so forth. This is one of those times.

We forget, as one of the characters, Hector Tobar, who was actually a journalist at the Los Angeles Times when I was creating Twilight way back then almost 30 years ago, and he really showed me around the Latinx community, I needed him to help translate and so forth. He points out that we were in a kind of a sleep mode until the pandemic, and until the murder of George Floyd that really burst us forward in the way that we are right now. We can only hope that while this window was opened, sadly because of a violent thing, that while the window is open we can try to deal with the problems that racism causes in our community.

Brian Lehrer: Now that your season with Signature Theater Company has resumed, you added some new material after the pandemic hiatus?

Anna Deavere Smith: I did. Hector, for example, I went back and talked to, in large part because there were certain things about the play that somebody who maybe wasn't even born then would have forgotten. For example, that there were actually two trials, not just the one that brought back four officers not guilty. That George Bush called for a second federal trial that put two officers in jail and let other two go free.

I really went back to Hector to get information about that because he called me up from the courthouse with a gas mask waiting for me to come down to the courthouse expecting another riot in that second trial. He ended up in that time he became a Pulitzer Price writer and a whole lot of things. It's not like his life stood still. He's a big voice actually in the Latinx community, in particular, of activists and academics, intellectuals, and artists. It turned out that he had other kinds of reflections that I think enrich the story.

Also, sadly because of the abuses against Asian Americans that we've also been confronting of late, I wanted to make the story of what happened in the Korean American community clearer for people who weren't there, who wouldn't remember that during the uprising, riot, revolution, civil unrest, whatever you want to call it, that a lot of Korean American businesses were attacked and burned.

Brian Lehrer: When you played all the characters, from the real estate agent once married to Gig Young who holed up in the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel, to Rodney King's aunt, to a Korean store owner, to one of the police officers who stood trial, there was, I guess, the paradox of one body containing these totally different ways of seeing the world and what happened. Now the cast is carefully constructed to mirror the racial and gender identities of the people they are portraying, although that gets deliberately mixed up at times. I won't do spoilers, but how does the storytelling gain or lose from that?

I wonder if, with as much as people talk about co-opting other people who individuals shouldn't be allowed to represent in works of theater or any works of art, has your thinking evolved, even about the legitimacy of one person playing all these different roles?

Anna Deavere Smith: I wouldn't say that because I think that number one, it's partially a political question but also an aesthetic question, so I certainly wouldn't throw the baby out with the bathwater in my case. I think you've probably interviewed me before when I've said that my grandfather said if you say a word often enough it becomes you. My goal in these 30, 40 years has been to become America word for word. Playing a rodeo bull rider, who I'm sure voted for Trump, on the one hand, on another hand Angela Davis. I wouldn't throw that out at all, and I don't know what another director might like to do.

In this case, I decided that I would cast this, for the most part, in a way that people are playing their own races, as you say, with a few subversions or whatever you want to call that. I think by making that choice this time I was able to show how our race story is really not only in that Black/white paradigm the way we like to think. I think it shows the complexities of it probably in starker relief than it was just me playing all these different races. Also to say that I'm crazy about the actors. [laughs] I'm just crazy about what they've done, and I think that Taibi Magar, the director, and all the designers as well have done an extraordinary job.

Brian Lehrer: You said if you say a word long enough it becomes or you become it. I read where you said, "If you keep people talking long enough, eventually they say something poetic." So everyone is quoted verbatim in the play?

Anna Deavere Smith: Everybody's quoted verbatim in the play. I think we're representing about 43 people; I haven't counted. Of course, I talked to 320. Getting to that is not easy. I just believe that certain people are organized in a way that they can communicate very, very vividly. It has nothing to do with education or anything like that. There are just certain communication talents that people have that we might not think about if they're not running for office or trying to sell something.

Brian Lehrer: Anna Deavere Smith with us for another few minutes. Her play Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 now running in New York with the Signature Theatre Company. Can we talk about the AA meeting - that's the name of the key scene - so our listeners know, and how one of the jurors describes their deliberations in that second federal trial of the officers. For those who don't know, after the first trial and the violence, the federal Justice Department brought civil rights charges against the officers, and two were convicted.

You got an amazing story from one of the jurors that's included in the play. "Deliberations become some kind of encounter session where the jurors had to go through some stuff to be able to reach a verdict." What she describes, is that, and almost breaking down, the only way through to facing the truth in a fraught situation like that?

Anna Deavere Smith: Thank you for bringing that up. I have to say, first of all, what a moment of joy, because that used to be what was called - to use George Wolfe, who was one of the directors of the many versions of the play - my eleven o'clock number when I played that juror. Who then did, in talking to me in an interview, what I had done throughout the whole play when she started to act out all of these different people on that jury. One day in rehearsal, as I was watching Tiffany Rachelle Stewart, our wonderful actress, I realized, oh my God, dramaturgically I could break this down so that everybody in the cast is playing a part.

It still is that sort of moment, when an audience feels free to laugh out loud at something that's tragic because I think they see their own absurdities. What she gets that in it, this juror, is saying that they couldn't get to the verdict. They kept procrastinating, going back to the hotel, doing all these things. They just couldn't get to their work until they started telling personal stories. Just emotionally breaking into personal stories. As she says, once they could confront their own guilty - she called it their own guilty - or whatever they had inside of them that felt guilty, their personal guilt, they were actually able to sit down and do the work.

That was something that appealed to audiences in the '90s, I hope that it's relevant to audiences now, which is that we really aren't going to be able to get to this awful situation that we're in on the streets with our police, in our courtrooms, in our schools, in our healthcare system, until we do deal with that which is personal inside of us. Now, people who are in policy probably don't want to hear me saying that. They want to just get right to the work, and they should, but they may confront it too in their own boardrooms. That people are sitting on their own not so obvious internal guilt that may have [unintelligible 00:13:50]. They have something to do with other things.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe, hopefully, we're in the midst of that process as a nation now. Rodney King famously asked, "Can we get along?" trying to quell the violence back then. You said the question is, "How shall we gather?" In our last minute or even less than a minute, can you talk about that distinction?

Anna Deavere Smith: Yes. When you say how can we get along or how can we come together, we assume that means that we will agree, which we don't. I believe that any productive conversation-- any productive work, let's not use that word conversation because at this point we're way beyond talking, is going to call for discord and more discord than some people can tolerate. I think gathering is a willingness to be there, a willingness to show up, a willingness to be present to do whatever it takes to get rid of the things that are most egregious.

Brian Lehrer: Anna Deavere Smith's Twilight: Los Angeles 1992 is in performance until November 21st at the Signature Theatre on 42nd Street. You will even learn that twilight does not refer to a time of day. Anna, thank you. Always so good to have you on.

Anna Deavere Smith: Just thank you very much for taking the time.

Brian Lehrer: The Brian Lehrer Show is produced by Lisa Allison, Zoe Azulay, Amina Srna, and Carl Boisrond. Max Bolton helping out for a few weeks. Zach Gottehrer-Cohen works on our daily podcast. Our interns this fall are James O'Donnell and Prerna Chaudhary. We have Liora Noam-Kravitz spinning the dials at the audio control. I'm Brian Lehrer.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by

00:15:42] [END OF AUDIO]contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.