Reporters Ask the Mayor: City Council Overrides Veto and More

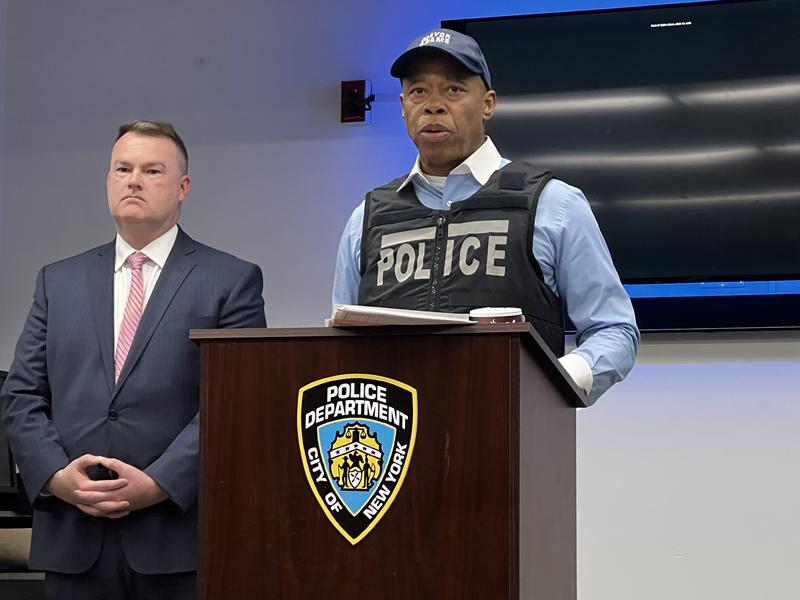

( Bahar Ostadan / WNYC News )

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We'll begin today with our lead Eric Adams reporter, Elizabeth Kim, who many of you know comes on with us most Wednesdays after the mayor's Tuesday news conferences. This week, there was big news. The news conference happened to come on the same day as the biggest legislative defeats for the mayor since he took office in 2022. City council overrode his vetoes of bills requiring more police transparency about who they interact with and one further limiting how people incarcerated in city jails can be kept isolated. Here's speaker of the council, Adrienne Adams, yesterday before the override votes.

Speaker Adrienne Adams: The resistance to this legislation is disturbing. The resistance to truth-telling of data, of who is being stopped in the city of New York, is disturbing to me. It should be disturbing to everybody.

Brian Lehrer: Here's Mayor Adams yesterday at his news conference. This was also before the vote.

Mayor Eric Adams: The council's goal of increasing transparency in government, I believe in it. I believe in it 100%. This is my life's work. This is what I have committed myself to do, but at the same time that I talk about transparency, I talk about public safety. We can have public safety and justice. They can coexist.

Brian Lehrer: Now, WNYC and Gothamist City Hall reporter Elizabeth Kim on all of this and more. Hi, Liz. Welcome back to the show. It's another Wednesday.

Elizabeth Kim: Good morning, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: They actually seem to agree on the goals, just not this specific new requirement in the How Many Stops Act of recording race and other demographic information on what's called "Level 1 stops," the most minor interactions or among the most minor, what they call investigative interactions with the public. How far apart are they really despite the veto and the override?

Elizabeth Kim: I think they actually are pretty far apart. The mayor does say that he believes in transparency. The question is, how do we accomplish that? I think in the clip you played of the speaker, that was one of her sharpest rebukes of the mayor and his administration that I've heard. She talks about, it's a resistance to truth-telling. I think they are very far apart on what's happening on the ground to Black and Latino men. The mayor says, "Yes, I do believe in transparency." The question is they seem to be seeing a very different reality in how policing is being played out on a daily basis for New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: I guess, but it's not like the mayor denies that there is racism in the NYPD. Here's a minute of him talking about that at yesterday's news conference.

Mayor Eric Adams: Anyone who believed that isms don't still exist in our society, really have their heads in the sand. Isms exists. Anti-Semitism, racism, Islamophobia, denials of women are moving forward in society. That's why we rolled out our Women Forward plan. They all exist because we're human beings. We recruit from society. If you recruit from society, you're going to bring in those isms.

What we must do, identify them quickly in areas that we correct behavior. We need to do so immediately in areas where we don't believe a person is suitable after their probationary period based on their actions to be a police officer. We should move forward and have them removed from the department. That's what you see when we're cutting down the amount of time that we're reviewing those officers that are having some real disciplinary issues.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, what was the context for that answer and do the facts seem to back up what he says is changing in his administration with respect to police accountability?

Elizabeth Kim: That was the mayor's response to a question that I put to him. I had asked him, "Do you believe that the NYPD is still using racist tactics? If so, what do you think we should do about it?" That is his answer there. I chewed on it a little bit and I spoke to someone in Adrienne Adams's staff about it. They made a good point to me. When the mayor talks about things like isms and how he's handling individual complaints against officers, he's talking about accountability on an individual level.

What the council has wanted to do with their legislation is implement a kind of institutional accountability so that they're looking at patterns, they're looking at trends, not necessarily holding an individual accountable for how they are policing but looking at the NYPD as a whole. I think that that's a very important distinction and difference in how they look at reforming the NYPD.

Brian Lehrer: What's your take on the people in the largely Black and Latino districts most affected by NYPD behavior and practices? Presumably, their city council members know the sense of their local constituents pretty well, which is why they all voted, and then even with a big spotlight on them, voted to override and maintain this bill that they passed. These are also parts of the city where Adams racked up his biggest electoral margins, including in the Democratic primary in 2021, against some more progressive and police-skeptical candidates. Is there uncertainty or mixed views about what the actual people of New York and the districts most affected tend to want on this?

Elizabeth Kim: The mayor still has strong support in the Black community in particular. Some of that is eroding. We've seen that in polls. A lot of that has to do with budget cuts and the migrant crisis. They're twin feelings within Black and Latino communities. On the one hand, they feel that they've been under-resourced when it comes to getting the kind of police protections that they want. They also feel that they have been targeted for over-policing and racist policing.

I will note that the speaker did go on WBLS. That's a station that the mayor often goes on. That often takes the temperature of what or how a lot of Black New Yorkers feel about the issue. I was told that a lot of the callers who called in over the weekend when she was on did speak about the feelings that racialized policing still exists in this city. I think that what you'll see is you have a lot of mixed feelings. People want to be protected for sure, but they don't want to be racially targeted, of course.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you live in a neighborhood where you think crime is a problem and where you think over-policing is a problem, they often go hand-in-hand, then how do you feel about this whole conflict between the mayor and city council on these bills? First priority now for Black and Latino New Yorkers who are on the receiving end of police behavior more than other New Yorkers in general. That's just a fact.

You get first priority on the phones here. No matter what neighborhood you live in, but especially if you live in a, let's say, lower-income or higher-crime neighborhood of the city. Whether or not you voted for Eric Adams in the primary or the general election in 2021, how is this striking you? 212-433-WNYC. Have you felt yourself taking sides on this conflict between the mayor and the city council, specifically over the How Many Stops Act?

We'll get to the other one, the solitary confinement one as well, but particularly on How Many Stops and the mayor's argument that he made here on Monday that he's been making everywhere. He couldn't make it in the last week or so that these Level 1 stops, where they're not really investigating the person who they stop, shouldn't bog down the cops with paperwork. It's in the interest of your public safety for them to not have to do that. Obviously, your city council members, I think, what, Liz? 42 out of the 51 of them-

Elizabeth Kim: That's correct.

Brian Lehrer: -feel differently.

Elizabeth Kim: Right.

Brian Lehrer: 212-433-WNYC. If you feel like this is personal to you potentially or has been in the past in any way, 212-433-9692. Give us a call and help us report this story. Because I think this is vague still to a lot of people and has been an abstraction to a lot of folks even as concretely as the mayor and the city council speaker have been trying to talk about it. What's your best understanding of what this bill, now that it's definitely gone through, actually will change?

Elizabeth Kim: Well, as the speaker has said, a lot depends on implementation. That has been part of her frustration. The frustration of council members who support the bill is the way that the mayor has framed it is he has proposed a way of implementing it in, really, the most difficult way possible, which is paperwork. There's no reason why it has to be done on paper.

The speaker has made the argument that it can be done using technology that the NYPD is already using, which is they all have smartphones. They are already using apps and they're capturing data already about their interactions with civilians. In a sophisticated way, they wear bodycam footage, for example. At the end of the day, an officer docks that footage. He or she sits at a computer and then they are already categorizing even Level 1 interactions.

There was a caller that called in when the speaker was on with you, Brian, his name is Edwin Raymond. He is a former NYPD officer. He talked about it on your show. Then later, I called him and he walked me through it as well. He said, basically, they're already doing some of this. He told me that he feels it only takes on maybe a few minutes to what they're already doing at the end of the day.

Now, he told me that it can be done at the end of the day. That is another point of contention between the mayor and the speaker. The mayor has said that officers would have to do it in the moment so that as they're looking for a missing child, they would have to stop and fill out these forms. He's right. That could prolong the amount of time that's taken for an investigation.

Again, the speaker's response is consistently, "You, Mr. Mayor, will implement this and you will set the rules for how this is going to be done." I'm sure that the council will want to have input on that. I'm sure they'll try to push the mayor to do it in the easiest way possible, but also to make sure that the officers are, in fact, doing it. We shall see. The first report is due in about six months.

Brian Lehrer: We'll see how much they try to get around this at the NYPD and at city hall since, as you say, the city council passed the law, but it's up to the mayor, the executive branch to whom the NYPD reports to implement it. Here's more of the mayor from yesterday's news conference talking about his personal commitment to fighting racism and policing.

Mayor Eric Adams: The uniqueness of this moment is that we have a mayor that has not only been an advocate for this. I've been the leading voice on this. I'm not only an advocate. I'm a mayor that did this job. There isn't another mayor in history that I can think of that actually have been on the streets doing these interactions and also advocated to improve on how these interactions are done. There's a unique moment that we are in. That's why I think Councilman Yusef Salaam brings a unique perspective. I bring those perspectives. Every other mayor had to turn to their police commissioner and say, "Hey, I need you to figure this out." I don't have to turn to my police commissioner to say, "I need you to figure this out."

Brian Lehrer: It's interesting, Liz, that he mentioned Yusef Salaam there. How kind of, I don't know, a strange act of fate or something like that that he, of all people-- Of course, he was one of the exonerated Central Park Five. Now, he just got elected last fall to New York City Council long after he had spent 10 years in prison after being wrongfully convicted of that attack on a Central Park jogger way back in 1989. Now, he got elected to city council.

He got appointed the chair of the city council's public safety committee. Certainly, an act of historic justice in that. Then over this past weekend, he gets stopped by a police officer when he is driving his car. Nothing much happens, but the issue is raised of the officer not disclosing to Salaam, why he was stopped when Salaam asked. Here we are with one of the most famously wronged by the police New Yorkers in all of history, thrust right into the middle of the debate right before the veto override vote.

Elizabeth Kim: I know, Brian. You can't make this stuff up. You couldn't have scripted something more dramatic. All of us have been waiting to see how this dynamic plays out between the mayor and Council Member Salaam. To the point you made earlier about how do members of the mayor's base, particularly Black and Latino voters, feel about this issue. It's interesting that in recent days, the mayor has leaned on his role as an advocate, as an activist. As we know, he was a member of 100 Blacks in law enforcement who care.

He spoke out against stop and frisk. I think it's notable that he's trying to remind the public of that because he too, he's very aware that this is a concern in Black and Latino communities. They do have a history of being the target of police officers. In this moment, he's seeking to remind his constituents about his role as an advocate. Also, again, he has made public safety a priority. Coming into 2024, he was very vulnerable. He's coming off historically low poll ratings.

He's under a federal corruption investigation, although he hasn't been implicated. Coming into 2024, it seems as if he is back in his campaign mode, right? He's really reviving a lot of slogans he used during the campaign. Public safety is the prerequisite to prosperity. Now, this other slogan, which he also used during his campaign, which is we can have public safety and social justice. We will see how that plays out. I think his critics would really push him on, "What are you doing for the social justice part?"

Brian Lehrer: Milta in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. Hello, Milta.

Milta: Hi. Thank you. This conversation is an imperative. I live in the Bronx. I grew up in Manhattan. I am a Latina woman. I have brown and Black family members. I can tell you that not only is this a subject matter of discussion for our children and us, the adults, and the adults that grew us learning how to manage this corrupt institution that keeps trying to blame individuals like the bad apple. The system itself needs to be accountable. If we are asking the mayor to make this accountability part of the patrolling officer's duty, then why do we have to continue to fight our own mayor to assure that he does what he said he was going to do? We have history with this. This is not news.

Brian Lehrer: Milta, thank you very much. Let's take another caller from the Bronx. Michelle, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Michelle: Good morning. I'm also from the Bronx. I actually grew up in Atlanta. I'm white, grew up in Atlanta, in a minority area as well. What really shocked me was the difference in how the police officers act in the Bronx versus where I grew up. In the Bronx, if you go and ask them for help, they will turn their backs on you. If you try and wave them down, they drive right by you. The only thing I've really seen them do in our neighborhood is if there's a shooting, they will park their vehicle and flash their lights all night long right in front of my window. [chuckles]

I'm sure it's waking other people up too. It's to deter, I guess, that from happening again for a little while until things cool down, but I'm very unclear as to what the police officers think their job is because it seems to be different from my experience growing up with the police officers in Atlanta. I do think that individuals need to be put on probation and retrained. Also, institutionally, it needs to be defined and communicated to the officers and to the public as to what to expect from the police officers.

Brian Lehrer: Michelle, thank you very much. Interesting comparison, at least in her experience between police in Atlanta and police in New York City, Liz. I don't know if any of that is reflected in stats or the conversation at the political city hall level, but any thoughts on either of those two callers?

Elizabeth Kim: Well, it's a small sampling, right, Brian? Those two callers who live in minority communities, they're talking about the police. They're talking about their own desire for some kind of reform but transparency, right? That speaks to what the council has been arguing is we need more transparency. Over the years, the police have implemented some changes. I think the most notable one was wearing bodycams, but there have been complaints about that.

There was a recent ProPublica story that spoke about how even though there is this extensive bodycam footage, the NYPD rarely releases it. In fact, many people noted over the weekend when Council Member Yusef Salaam was stopped by a police officer that many people were stunned that the NYPD released the footage so quickly. That's not usually the case.

Brian Lehrer: Listener writes in a text message, "I'm a South Asian woman hit by a police baton at a protest. Will the NYPD technically be required to report the indiscriminate and split-second interactions with civilians? Specifically, will this bill deter them from, for example, the way they were blindly hitting protestors in 2020?" That's an interesting subset of this bill or of this whole topic of police accountability.

We know there was police misconduct. Mayor de Blasio, who was in office at the time, wound up admitting it in some of the post-George Floyd murder protests in the city. Where does police interaction with protestors come into this in terms of any interactions that will now newly have to be documented by race, age, gender, any other ways, and if they already needed to be if you know?

Elizabeth Kim: I don't know because what this bill refers to are all investigatory interactions. I don't know that it sounds a lot more of a serious interaction if a police officer is actually using force or violence against a civilian. I don't know where that fits in. I would think there's already some kind of category and through bodycam footage. I don't know how that is reported, for example.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to take a break and then we're going to continue. I'm going to ask you about traffic stops in particular because the stop of Council Member Salaam over the weekend, besides shining a light in a different way on the How Many Stops Act veto override that was coming, it also put traffic stops back into the conversation maybe in a new kind of way or a revised kind of way even though traffic stops already had to be documented by police officers.

We'll talk about that and a reform that the mayor seemed to endorse on this show and play that clip from Monday that, who knows, might lead to an agreement between the mayor and city council on another way to reform the NYPD. We'll get into some other issues too that may have come up at the news conference yesterday. Stay with us.

[MUSIC - Marden Hill: Hijack]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with our lead Eric Adams reporter, Elizabeth Kim, who comes on with us most every Wednesday after the mayor's weekly Tuesday news conference with clips and analyses. To take your calls, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. You can call or text as we continue to talk mostly about the confluence yesterday of the mayor's weekly news conference and the big news out of city council that they overrode the mayor's vetoes of bills requiring more police transparency and less solitary confinement in the city jails.

When the mayor was here on Monday, there was one answer to a question I asked that could theoretically give way to another police accountability reform measure that the mayor and council might agree on. We were talking about the police traffic stop of Council Member Yusef Salaam and that the officer did not answer Salaam's question of why he was pulled over. It is currently legal.

It's okay for an officer to refuse to tell a driver why they were stopped, so I asked the mayor this, "Some people say change that law to require that transparency both for police accountability and for public trust in the NYPD. Maybe human nature says, 'If they won't tell us why we're stopped, we'll be more suspicious of their motivations.' I'm curious, from your experience on the force and, obviously, as mayor, would you support or oppose that kind of change in the law?"

Mayor Eric Adams: I don't have a problem with that at all. Anything that we can do to, number one, deescalate a situation, number two, continue to build that relationship between police and community is a real win for me.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, I don't know how big an issue that is or if there are good reasons for a police to have that discretion not to disclose. Maybe if they're in some kind of investigation and they don't want to tip people off to something, I don't know. I wonder if you think since the council member, Salaam, raised this as an issue after the stop and the mayor said he has no problem with that kind of reform if something might come of that.

Elizabeth Kim: Well, I think you did open up by the mayor responding the way he did to your question, Brian, that it does open up an opportunity for the council, if not the mayor himself, to propose something. That was one of the major questions that came out of the stop was the reason that we learned later afterwards from the NYPD that the council member was pulled over was because he had illegally tinted windows, but that was never mentioned based on the bodycam footage to Salaam from the police officer. Then the question becomes, why wasn't it mentioned?

The council member himself was heard asking in his own recording at least, "Why was I pulled over?" The police officer just wishes him a good night and leaves. Why didn't the police officer tell him? Because, presumably, you would think that you'd want the person to know so that he could correct the offense so that he won't be pulled over a second time. That was kind of perplexing. The mayor was asked about that again both on your show and I believe he was asked about it also yesterday. I know on your show, he said that it's possible that the officer didn't hear him. Then, again, shouldn't the officer proactively be telling someone that he has stopped over for what law exactly he broke?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that's interesting. We're pulling up the 15-second audio of that interaction that was released. We'll play it in a second. One of the things that I think I saw in your reporting, Liz, is that even though traffic stops already had to be documented, they will not be newly included in this How Many Stops Act. They already had to be documented in demographic terms because there's been so much, "Driving while Black," that kind of thing in disparate rates of pulling over drivers of different backgrounds. That already had to be disclosed. In the Adams administration, they have not closed that gap. Maybe the opposite?

Elizabeth Kim: Are you talking about the racial disparities?

Brian Lehrer: Correct.

Elizabeth Kim: We haven't had a lot of data. That was a newly implemented law. We got data on traffic stops for the first time last year. What it showed was that it was around about 90% of people who were searched or arrested in these stops were Black or Latino. It's a little bit lower than pedestrian stops, but that's still incredibly high. We don't have anything to compare it to because that was the first time that this kind of data was released.

Brian Lehrer: I see. Here's the 15 seconds of audio that was released of the interaction between the officer and Council Member Salaam. Some of this is a little hard to hear, so listen carefully.

Officer Kentucky: Hello. I'm Officer Kentucky from the 26th Precinct.

Council Member Yusef Salaam: I'm Council Member Salaam from-

Officer Kentucky: Oh, council member?

Council Member Yusef Salaam: -this district, District 9.

Officer Kentucky: Oh, okay.

Council Member Yusef Salaam: Is everything okay?

Officer Kentucky: Yes. You're working, right?

Council Member Yusef Salaam: Yes. Can you tell me why I was pulled over?

Officer Kentucky: All right. Thank you, sir.

Brian Lehrer: At the end there, "Will you tell me why I was pulled over?" The officer just says, "Thank you, sir," and walks away. The mayor was saying on the show, as you just cited, it was noisy there. He is not even sure from that audio whether the officer heard Council Member Salaam. What would be the motivation to not tell him?

Elizabeth Kim: It's not clear. That was the question. One of the theories that was floating around was that the council member, by identifying himself as a council member, was using his position to try to skirt a ticket or something like that.

Brian Lehrer: All he did was say who he is. He didn't ask for anything.

Elizabeth Kim: Exactly. Exactly. I think that there would have been criticism to had he not identified himself as a council member, that perhaps he didn't want the police officer to know that he was an elected official. I think that could have worked both ways.

Brian Lehrer: It just seemed like such a normal response by the council member to me, listening to that audio, which, by the way, I want to credit The New York Times because that's where that audio bite was that we grabbed it from. The officer walks up and says, "Hi. I'm officer so and so from the such and such precinct." The driver says, "I'm Council Member Salaam from the 9th District, this neighborhood." It's about as straightforward and one on one as it sounds like it could be.

Elizabeth Kim: Right. Now, on your show and also yesterday when the mayor was describing this exchange to reporters, he calls it the picture-perfect stop. I think a lot of people would ask what you've asked. Why didn't the police officer just tell him what he did wrong? The reason for the stop. That seems to be a real critical piece of information. Perhaps then that would have become a more perfect stop, I would say.

Brian Lehrer: Mary in Somerset, New Jersey, you're on WNYC. Hi, Mary.

Mary: Hi, yes. I was just going to say that I think the piece that we can acknowledge is the fact that there's a lot of trauma in the Black community around this issue. In light of that, even though maybe disclosing the reason for the stop isn't ideal for the officer or even for the driver, I think the fact that there's been trauma, it just makes sense. It might be the better option to just disclose it because there is this trauma history.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. Deborah on Long Island, you're on WNYC. Hi, Deborah.

Deborah: Hi. Hi, Brian. I'm an activist with the police accountability movement on Long Island. I just want to bring out that Long Island has some very serious problems and with regard to policing practices and patterns. For example, Suffolk County is under a DOJ settlement agreement. It is monitored by the Department of Justice. Nassau County officials refuse to speak with activist groups, which is worse. For example, there was a recent $35 million jury award against Suffolk County for the alleged police speeding death of Kenny Lazo. It took 15 years to get a civil court justice and federal court for the family of this young man who left a child and a significant other, not to mention his other relatives who loved him.

Brian Lehrer: Deborah, just to keep us on topic, do you think that in whatever town on Long Island you're talking about, there is this kind of data reporting requirement or if there was that this incident that you're describing might have been averted?

Deborah: This is a complicated issue. Yes, data reporting is extremely important, especially if it's published in a usable way and if the police department actively uses it to get a clear picture of the patterns and practices of the police department, especially with respect to non-safety stops. Not exclusively, but that's a great way to see where personnel is being used because Suffolk County, for example, has the highest vehicular fatality rates partially because we wonder where personnel is being employed. Is it being employed in areas to go after people for non-safety stops on pretext or is it an issue of really being concerned with general welfare?

Brian Lehrer: Deborah, I'm going to leave it there. I thank you for chiming in with all that. That's great context and regional context. Don in Teaneck, you're on WNYC. Hi, Don.

Don: Hi. How are you? Thanks for taking my call.

Brian Lehrer: Sure.

Don: It seems like he was a very courteous policeman. Most the police aren't courteous. That gentleman, the police officer, he wouldn't have to split hairs like we're doing this morning.

Brian Lehrer: Don, thank you very much. Yes, and that was kind of the mayor's point, Liz, right, about the particular interaction like beyond the How Many Stops Act? The particular interaction between the council member and this particular police officer, the mayor said this was a perfect interaction on both parties' parts. The police officer identified himself. The council member was courteous back, asked what was wrong, "Is there anything wrong?" The officer said, "Okay, go on your way." Mayor says perfect stop on both parties' counts. Don says, "Hey, let's give this officer some credit for being straight up."

Elizabeth Kim: I do wonder, though, whether our standards of police and civilian interactions or expectations at this point are quite low given the volatile history and the more violent interactions that we've seen make headlines. I think that listening to it, yes, the officer was courteous, but he should be courteous. Again, let's think about what he didn't say and, in a way, not answering the question. Let's say he did hear the council member, but he didn't want to answer it. That, I think in the council member's mind, does tarnish that interaction because he asked him something that seemed very basic and very pertinent to the moment as to why he was stopped.

Brian Lehrer: He just walked away although we have--

Elizabeth Kim: He walked away and then that doesn't really come off as-- it's far from the perfect interaction from the council member's perspective.

Brian Lehrer: Although some other people, we have a caller to this effect that I'm not going to have time to take, but I see it came up at the news conference yesterday too, is did the officer give the council member special treatment because he's a council member? That kind of privilege, no matter who the council member is, should not be afforded either if he had illegally tinted windows. That's considered a hazard in New York State. I guess the car was previously registered in Georgia and he hadn't changed it since he came up here or brought the car up here. Then why does he get special treatment and is that good behavior by the officer either?

Elizabeth Kim: Correct. The mayor's response to that was, "This is at the officer's discretion." Again, it's discretion he used, which he also didn't explain to the council member that I am using my discretion to not give you a summons about your illegally tinted windows.

Brian Lehrer: Here is a police officer calling in on the topic of discretion. Well-timed. Jane in Yorktown, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jane. Thanks for calling.

Jane: Hi. I am a police officer. I can tell you that when you're making a traffic stop, there's a lot to think about. You don't know what you have until you're at the car. You don't know the situation inside of the car. Any number of things like I personally know of people who have been seriously injured making traffic stops. I know many people who have been seriously injured making traffic stops.

Brian Lehrer: You mean police officers?

Jane: Correct, because I don't--

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Jane: Yes, because I don't know other people who make traffic stops.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] I didn't know if you meant the drivers. That's all, but go ahead.

Jane: No, I mean police officers. A classmate of mine had his hand hit by another car that was going past him. His one hand was basically broken by the side mirror of a car that came by too closely. I injured myself one time when a car came by too close. I had to throw myself up against my car in order to not be hit by the car that was passing me. These are all the things that you are taking into consideration.

You're trying to make the traffic stop quickly, safely, and as courteous as you can possibly be. That's just the traffic on the side of the road that you have to be concerned about. There also may be something in the car that might be popping out and hurting you. There are many, many considerations. I do think that that was an excellent traffic stop. I do think that once the councilman identified himself, he put his thumb on the scale.

Brian Lehrer: Right.

Jane: Flat out, straight up, he put his thumb on the scale.

Brian Lehrer: It was implied, "I deserve special privilege."

Jane: Correct. That is correct.

Brian Lehrer: What about the officer's decision not to answer, assuming it was a conscious decision, not to answer the question of why he was stopped? In your experience as a police officer, does that surprise you or are there legitimate reasons for that?

Jane: I think that knowing that there's bodycams, knowing that you're not speaking to a council person, you know as a police officer that the best way for you to be reassigned is to mess up that traffic stop in any way. To keep it short and keep it sweet, because you have to pick your child up from the bus every day, and you don't need your precinct to change. You don't need to have to hire a babysitter because, now, you have to take extra time to get to work in the mornings. Now, you have to have somebody else drop your children off at school.

Brian Lehrer: Right, so it's the most safe, risk-averse, self-defensive decision-

Jane: Correct.

Brian Lehrer: -at that moment knowing he was interacting with a council member.

Jane: Because your position where you work could be at stake in that one interaction in a heartbeat.

Brian Lehrer: Jane, thank you for your call. I really appreciate it. Liz, I want to touch one other topic before you go from the mayor's news conference yesterday, but I don't know if you want to react to those last couple of calls.

Elizabeth Kim: No, I think she makes a very good point. He was not just interacting with any council member, right? He's interacting with Yusef Salaam, who has a national profile as one of--

Brian Lehrer: Which the officer may or may not have known.

Elizabeth Kim: That is true too, Brian. We don't know whether he knew that. You would presume he would if that's his precinct and that is the council member's district. There've been quite a lot of stories written about Yusef Salaam. Yes, perhaps he didn't know. If he did know and he has bodycam footage, that's a reason why, for self-preservation, he wants to keep the exchange as short as possible and just move on his way.

Brian Lehrer: Well, yesterday's news conference looked to me, I watched most of it, was if not only, it was overwhelmingly about these bills. Of course, there was so much else in the mayor's State of the City speech last week. When we took calls for the mayor on Monday, New Yorkers were raising lots of other things, Pre-K and 3-K funding, supportive housing, the asylum seekers, and more. You brought one other clip that's on a whole other topic, the migrants, and interacting with something. A lot of New Yorkers may not think of it in conjunction with and that is the shortage of lifeguards in the city. Should we just play the clip or do you want to set it up?

Elizabeth Kim: That's right. The governor has announced a state program in which she is going to make several thousand jobs available to migrants who have work authorizations. The mayor was asked to respond to this idea and this is what he said.

Mayor Eric Adams: We need to find a creative place in a way that we've stated over and over again about allowing people to work. We have a lifeguard shortage. I would love to use migrants and asylum seekers to help with the lifeguard shortage.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, it doesn't get discussed probably enough when there's this assumption that they are just a burden on the city, at least in the short run, that there are also needs that they could fill.

Elizabeth Kim: Right. I think there's a compelling policy argument that in a moment where government is struggling to find people to work, whether there's not an opportunity here that government can use, can leverage to give these migrants an opportunity. What was interesting there was the first job that came to mind for the mayor was lifeguards. I'm not sure why he thinks that people from South America or other parts of the globe might be particularly suited to become lifeguards, but that was what popped into his mind.

Brian Lehrer: There we leave it for this week with our city hall reporter, Elizabeth Kim, who generally attends the mayor's Tuesday news conferences and generally shows up here on Wednesday mornings with excerpts and analyses and to take your calls. Liz, thanks as always.

Elizabeth Kim: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.