Reporters Ask the Mayor: Homelessness on the Subway, Mayoral Control of Schools and More

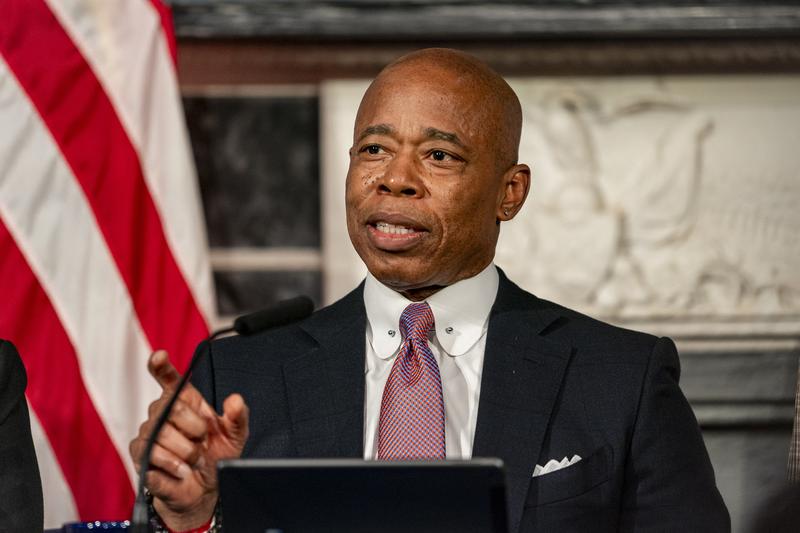

( Peter K. Afriyie / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We'll begin today with our lead Eric Adams reporter, WNYC and Gothamist's, Elizabeth Kim, who usually joins us on Wednesdays after the mayor's weekly Tuesday news conferences. Remember that's the only time each week that he takes questions from the City Hall press crew on topics that they choose rather than those dictated by the mayor's office.

As it happens, Liz asked a question yesterday that related to our segment on the show on Monday with NYPD Chief of Patrol, John Chell, about NYPD effectiveness with people in the subways who are apparently homeless or in severe mental health distress. Liz also asked the mayor if he would consider emulating Mayor Michael Bloomberg and take the subway to work. We'll play those excerpts and more, and open the phones for reactions. Liz, always good of you to come on on so many Wednesdays. Welcome back to the show.

Elizabeth Kim: Hi, good morning, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to start with your question to the mayor about the NYPD and people in apparent distress on the subways. Here's that.

Elizabeth Kim: Last week you were talking about when you went in the subways with the NYPD to see what they were doing. You said that one thing you didn't see them do was engage with people who needed help, people who appear to be homeless, people who appear to be in mental distress. You also said that under the previous administration, there had been a program in which officers were doing more of that with a team of social workers. I wonder what kind of model would you like to see? I know we have SCOUT. Do you want to see an expansion of that? Would you like to see the officers themselves trained in doing that kind of work?

Brian Lehrer: That's Liz's first question to the mayor yesterday. Here's a minute of his response.

Mayor Eric Adams: The Homeless Outreach Unit was a good concept. They saw the homeless every day, they built trust, they were able to move them out of the system. We put back and can go into what we did on how to use a combination of mental health professionals, outreach workers, law enforcement personnel, all of them combined together because you have to ensure the safety. Oftentimes people don't realize that you have to ensure the safety of outreach workers because some of those who are experiencing severe mental health illness, some can get violent.

You never want to put a civilian in the atmosphere or where they could be harmed in any way. We put this combination together, had thousands of interactions. We're seeing some success, and we're going to continue, we're going to expand on something. The commissioner gave me an idea that I think is really brilliant, I'm going to let him announce it himself, but we are continuing to evolve on how do we go into the subway system.

Brian Lehrer: Mayor Adams responding to the question from WNYC's Elizabeth Kim. Liz, how are you hoping to advance the story and the public dialogue around this issue that so many people care about both for the well-being of the people who are apparently homeless or in mental health distress in the subway system, and that perception of safety that seems to hang on that to some degree for the general public?

Elizabeth Kim: I wanted to know what the mayor was planning to propose. Last week when I made the observation to him that generally, we don't see the police engage either the homeless or those who appear to be in some kind of distress or need, and he acknowledged that. Given the fact that he acknowledged that and he said there was room for improvement, I wanted to know what kind of model does he want to see. This is not the first time that this has been a real issue in the City. This is not the first time that a mayor has had to grapple with this. What I was trying to push him on is, what kind of model do you like? How are you going to implement this?

What he says there is that he does like a model that involves both social workers and police. I will point out that that's not a model that everyone agrees with, but it's the model that he says he supports because he says that there are cases where if an outreach worker is trying to help someone who is mentally ill, that it can become dangerous for them. That's why he wants a police officer there. He also in that statement teases the fact that the police commissioner has come up with an idea, but that he's going to let the police commissioner announce it.

I also want to point out something afterwards that Deputy Mayor Anne Williams-Isom told me. She's the deputy mayor for Health and Human Services. I think what the mayor said last week and also what Chief Chell said on your program on Monday is that a lot of police officers are not comfortable with approaching the homeless. They have not been trained in this work. What the deputy mayor said to me was there may be police officers who are willing to do this work, who might want to raise their hands to do this work.

That would be interesting if it was by self-selection, that you had teams of police officers who say they're willing to be trained in this, they want to do this, and have them go out and start doing this, but we won't really know until the mayor and the commissioner come out and actually announce the plan. It will be interesting. We need to know what is the size of the investment? The program that the mayor is referring to under de Blasio was $140 million investment and it involved 18,000 City employees.

Brian Lehrer: It's amazing to me, first of all, that we're even having this conversation in 2024 still about whether police are being trained or being adequately trained to deal with people in mental health distress, whether it's on the subways or when they call 911. We also talked to Chief Chell on Monday about the police killing of a man named Win Rozario in Queens just the other week after he had called 911 himself seeking help because he was in a mental health crisis. The police responded. There are disputed accounts, conflicting accounts, but he had a pair of scissors in his hand, and his mother was there. Did the two officers who were there, did one of them need to fire a gun at some point?

The facts on that particular question remain in contention, but the fact that police are not routinely trained to deal with that kind of call and people they find on the street or on the subways in mental health distress when we've been talking about it in this City for decades. Probably since before I was doing the show, before you were on the beat, back in the 1980s, or sometime when street homelessness first became a big thing in the City in a contemporary way. Through Mayor Koch, through Mayor Dinkins, through Mayor Giuliani, through Mayor Bloomberg, through Mayor de Blasio, through Mayor Adams now, we're still having this conversation about whether police get trained for this at all.

Elizabeth Kim: Right. There are homeless advocates who say that police are not the appropriate people who should be doing this work. There are police who themselves say that they are not the appropriate people who should be doing this work. There is one incontrovertible fact, which is when you go on the subway, the City employees that you now see in the greatest number are police. They are at great expense to taxpayers.

The amount of overtime that taxpayers are paying for these police to patrol the subways could be going to many different things like subways and libraries. If we face that budgetary fact, I think it's time to raise the question, what should their role be? Is it time to address this long overdue conversation of do we need to change the role of police? Do we need to train them differently? Do we need for them to think of themselves differently?

Brian Lehrer: One of the reasons this even has come up right now, I think we should acknowledge, is the NYPD publicly bashing Daily News columnist, Harry Siegel, after Siegel criticized the NYPD brass, a couple of them for saying on TV that unless an apparently homeless or distressed person has committed a crime, there was nothing they can do. He was very critical of that in a column. Then they called Harry all kinds of names after that on social media. Do you think he's succeeded in prompting a few rounds now of developing further policy that might be both helpful to the people in distress and increase the general public's perception of subway safety, or do you think this was going on at this level anyway?

Elizabeth Kim: I think it did. I think to the mayor's credit, the mayor recognized it. When the mayor says something like that at a press conference, when he says that he took a tour of the subway with NYPD officers and he felt they didn't do enough to engage the homeless, that sends a very, very loud message to One Police Plaza.

Brian Lehrer: Did the topic of the NYPD bashing Harry Siegel come up again yesterday? If I may say, it looked like the Adams' administration or the NYPD leadership took a very, what I might call, Donald Trump or Cable News approach to responding to an earnest columnist, whether or not they thought his take was warranted or fair. I don't want to bash the police, I don't think we do that on the show.

They have a complicated and dangerous job to do, but saying, "Your latte-drinking friends," and referring to the defund crowd in that way, which isn't even Harry's issue, he was writing about more effective policing, not less policing. The more you think about it after having both Harry and Chief Chell on the show this week, is that their response to Harry on social media at least, it was like they were fighting a culture war, not doing public information that promotes and defends their policies. I'm just curious if that came up at all like that with the mayor.

Elizabeth Kim: It actually did because a reporter decided to ask the mayor, who has himself when he was a police officer, he was a vocal critic of the NYPD. He asked him how he would handle a situation like that where he disagreed with somebody, perhaps someone within the NYPD. The mayor gave a very interesting answer. What he said was his style was that if he had a problem with someone in the NYPD, he would address it privately.

He said, "I prefer to criticize privately and praise publicly." Now, people who remember the history of Mayor Adams speaking out against the NYPD may see it differently. It was very interesting that in that moment when the question was put to him, he basically gave the exact opposite answer of what the NYPD has been doing. That has been one criticism of their response to Harry's column because they could have easily reached out to him privately to express their concerns about inaccuracies in the article, for example.

Brian Lehrer: They do have the right to respond if they think a columnist or reporter takes a cheap shot, as they called it, then they have the right to respond whether or not what they were referring to there was a cheap shot by Harry Siegel, he disputes that. If they perceived it as a cheap shot, they have the right to respond and call it that in some way on the NYPD, or any public official, or any public agency not to be able to defend themselves against criticism in the press or be too precious about the way they can do it, but then where is the line?

Elizabeth Kim: Exactly. As you pointed out, their motto is courtesy, professionalism, and respect.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners as usual, do you want to weigh in or ask Liz Kim a question about any of the topics at the mayor's news conference yesterday? We just talked about one of them so far, we're going to get into other things now. Yes, we can keep going for third day this week on what you see and what you want to see police doing with respect to apparently homeless people or people in apparent severe mental distress on the subway for the sake of those folks and the sake of public safety or perception of public safety generally. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

We'll get into whether mayoral control of schools should be weakened. There's a new report at the state level that puts that into play. Should the mayor ride the subway to work from Gracie Mansion to City Hall, which we're going to talk about next. Do you care or anything else relevant? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, call or text. There's one other piece of this police and the apparently homeless or in mental distress people that I'm curious if it came up with the mayor or from advocates who you might also report on.

Because while I think Harry's column, and a lot of the discussion that we've been talking about so far, has to do with, yes, police should have a presence, yes, police should be engaging with those kinds of people on the subway. It's a question of how? It's a question of with people from the Social Services departments, or train by themselves, but there's an advocacy community that more says, "Leave them alone." Is there not?

Elizabeth Kim: That's right. Ironically this morning when I came in on the subway, I did see an outreach worker walk into the train. They approached someone who appeared to be homeless, and they said, "Hello, are you okay?" Then I think the person probably waved them away. It was an exchange that was under 10 seconds, for sure. Then the person said, "Okay, stay safe," and then walked away. These are not easy conversations. Last year around this time, I went out with a group of volunteers. It's a group that's headed by Norman Siegel, he's the civil liberties lawyer. It's a painstakingly long approach.

Their approach is just strike up a conversation with someone. It doesn't start out as, "Are you okay?" It's often, "Hi, how are you?" They introduce themselves, what seems like just friendly banter. I watched him approach someone and say, "I really liked your mustache." That made the man chuckle, and they had a conversation. Now, what's the point of this? Norman's point is that you don't go up to someone and just say, "Would you like a bed and a shelter?" He feels like that doesn't work. What he would prefer to do is to do this in a way that requires a lot more time and investment.

I saw him approach a lot of people. We were at South Ferry, and most of the people they talked to did not accept a bed. They would have maybe a 30-minute conversation with someone and only at the end would they say, "Would you like me to see if I can get you a bed?" Most of them would decline it, but they would take down their names, and they would make notes. The idea is the following week if they saw them again, they would just build on this relationship that they had established. Now, that takes a lot of time, and this is a volunteer group.

Norman's point is when the City is doing this work or when they're contracting people to do this work, they want to see results. That's why maybe a lot of outreach workers are measured on how many people that they speak to in a day. Norman isn't following that kind of benchmark. He knows that this is going to be slow and it's going to be hard. I think that's something for people to think about, how do we really want to do this?

Brian Lehrer: If he gets some meaningful results for 10 people, that's more his definition of success than filling out a form that he had contact with 100 people.

Elizabeth Kim: Correct.

Brian Lehrer: We have a related question from a listener in a text message. Listener writes, "What is the response time going to be for a social worker to show up at an emergency? How many social workers do we need in New York City to give the same response time as the Fire Department or the police? What would that cost per year?" That's a legitimate question. We have what, 35,000 NYPD officers and not that most of their time is spent responding to mental health crisis. I wonder if anybody's gamed it out or costed it out as the listener asks. What would such a mental health emergency response force require to stand up? Not that I expect you to know the answer.

Elizabeth Kim: Right. I think that's a great question. That's what I hope policymakers beginning with the mayor are trying to assess.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Let's go on. Let's see, actually, maybe we'll take a call or two on this. Let's see who got in early here. Michael in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Michael.

Michael: Hey, hi. I spoke to your screener and you used the phrase and I'm very glad you did, "a culture war." You were talking about, what's his name, Chell castigating Mr. Siegel for what he wrote, which was pretty reasonable, actually, Siegel. I think that's accurate. I told your screener, we live in a City where there's a number and it's hovering right around 50% of a police force who does not live here in the City. A less remarks number is the number of police officers and it's very high, it's in the double digits, who have never in their lives lived in New York City.

You also have the bizarrely, their main union PBA, I know there others, endorses the most anti-union candidate and party this country has to offer. It's very weird for a union. You have cops openly displaying punisher patches, and you know what that means. The first thing the police officer would ask you, excuse me, if you get in, again, not an argument, but you disagree with what they're doing or not doing, they're saying, "Who did you vote for?" I do believe the police force now sees itself as an entity distinct from the rest of the City and from City government, not particularly answerable to City government.

That culture war with what they perceive as the powerful class in the City, which is basically your listeners, people they believe have too much education, accurately a lot more money than them, a lot of them, and who look down upon them, and they have some justification for that as blue-collar people, as a servant class. There's a degree of justification for that belief on their part absolutely, but it is a culture war. I think that accounts for a significant percentage of the problems we're having with policing in New York right now. Not the violence, but the insularity, and then the lack of response to City government. That's my thoughts on the subject.

Brian Lehrer Lehrer: Michael, thank you.

Michael: I don't know if Ms. Kim has any thoughts on that.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Michael. Interesting set of thoughts there. Liz, if there's anything you want to say to it.

Elizabeth Kim: Now, I think that's absolutely right. I would say that during the 2021 mayoral campaign, there was a lot of discussion about the problems within the NYPD and its culture. Mayor Adams or Eric Adams at the time as a candidate made the argument that he himself being an outsider to the NYPD and being an ardent critic of the NYPD was the best person to help reform the culture, but we are yet to really see that.

Brian Lehrer: He would also point out, the mayor would, that the NYPD rank and file is majority, minority now, so it can't be simply written off. I know there are people who say, "Well, there's no Black, or Latino, or Asian when you're a cop. The cop identity supersedes all of that in real life." That may or may not be true, depending on the individual not to paint with a broad brush. It is different than Mayor Giuliani's police force, not to even hang that on Giuliani, just let's say the police force of New York City history until recent times.

Elizabeth Kim: No doubt, Brian. I remember Mayor de Blasio bringing up that point quite frequently too. On the other hand, are we looking at just individual personal conduct or personal values, or are we looking at the overall values of the institution? I think critics would say that that is what we should be focused on, is a broader institutional reform.

Brian Lehrer: We have two people calling in with experiences calling 911 on somebody who appeared to be in extreme mental distress. We're going to take those before we go on to this next topic of Mayor Adams riding the subway. Annette in Laurelton, Queens, you're on WNYC. Hi, Annette.

Annette: Hi. As a person who has a person I live with for a long time, all his life, the approach is, when I have to call on 911, I said, "Would you please send me an ambulance?" The person said, "What is the situation?" You explain the situation that's going on. At the same time, when both of them show up, the police and the ambulance, they're all in concern at what's going on at the person's house.

The biggest mistake, and I put it sometimes on those who have to call, is always make sure you ask for an ambulance because you're dealing with illness. Because if you just call for the police, that is not there expertise. Once you explain to the person that you called and he gives his dispatcher exactly what's going on, what kind of situation you're dealing with, then the both of them show up, and they understand exactly how to deal with it.

Brian Lehrer Lehrer: That's a great tint.

Annette: They must act, and the same thing in the subway system. The police officer is not a doctor, to just say this should be sharing of information right then and there. If the person is not bleeding or anything like that, and that police officer should contact whoever, I don't know how it works in the subway, but this is the situation, this is what we observed. When the person who specializes in dealing with a mental illness shows up, then you have the police because sometimes the individual could be very violent.

They have to work together. The main thing is that the professionalism comes in when you have to have the people who are in charge to control the situation. It's very hard because there are violent people at the same time. If that little information would help anybody, that's what I would say. Wouldn't that--

Brian Lehrer: Thank you so much for that, Annette. Really, thank you so much. That is such a great tip. I bet somebody is listening right now who is going to be in a situation with a person in mental health crisis at some time in the future, who's going to remember your call. They're going to call 911 and they're going to say, "Please send an ambulance." As you say, a police officer might have to come too, but at least there will be a medical professional there responding to a medical situation.

Liz, I love that call. Do you happen to know if paramedics, those people who do respond in ambulances, are trained for dealing with mental health crisis, as well as heart attacks, and strokes, and other things?

Elizabeth Kim: Under the Homeless Outreach Program that de Blasio established in 2019, there was training of FDNY. They used about 11,000 firefighters and 3000 EMTs and paramedics. Now, that program has been disbanded according to Mayor Adams. Why it was disbanded, I'm not entirely sure. I would think it had something to do with the pandemic and the temporary budget crisis that the City experienced before it got federal aid. It's very likely that it just fell under the radar a little bit.

Brian Lehrer: Because that was part of your question yesterday, why was that program disbanded? If I remember correctly, I watched the news conference, Adams hung it on there, de Blasio disbanding his own program, correct?

Elizabeth Kim: That's correct. I wanted to ask him about it because he praised the program. The mayor could bring it back if he wants to, but I will remind listeners, it was a sizable investment, $140 million.

Brian Lehrer: There's an interesting follow-up, perhaps one more like this. Mark in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Mark. You had an incident today?

Mark: Yes, hi. It just happened an hour ago. I was walking on my way to my yoga class [unintelligible 00:29:04]. Then when I turned the corner and I passed by this guy who was moving strangely, I just turned a little looking towards him, and then he went after me and went to kick really hard in my groin. Luckily, I got my hands there, so I stopped him. He had hit me a little bit, but it wasn't too bad. [coughs] I asked if--

Brian Lehrer: You okay?

Mark: Yes, sorry.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want to continue? It's up to you.

Mark: I'll continue. Then I continued, and I followed him, and I walked away from him quickly. Then I just felt like I had to call [unintelligible 00:29:50]. I called on 911, and then I followed him a block behind. I was watching him, and just walking along. I saw him going after another couple, threatening them on the street. Then I saw him walking to a child care place, another block up. Then finally, the cops came. I waved them and pointed out to where the guy was, and they grabbed him and stopped him. I went up there and they waved me over to interview me and to confirm the details. They asked me what happened, I gave them the details. They said, "You want to press charges?" I felt this guy was really mentally disturbed. I said, "What does that mean?" They said, "If you don't press charges, we let them go. If you do press charges, then we'll take them in for an assault." I was very--

Brian Lehrer: Conflicted.

Mark: I was very conflicted by the whole thing.

Brian Lehrer: What did you do?

Mark: They took him in, but I feel there should have been a third option on it.

Brian Lehrer: You did say, "Yes, press charges," to prevent--

Mark: I said press charges because I felt he was too dangerous for people on the street.

Brian Lehrer: What a horrible situation to be in. I hear the moral of your story at the end there, which is that you wish there was a third option.

Mark: Yes. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Mark, thank you. I hope you're okay. Thank you for sharing that. Liz, that's intense. It gets to that third option question, which whatever happened to, and this was controversial in and of itself, but the mayor's program, which we've talked about and which was a big thing in the City for a little while, Mayor Adams program, to remove people in apparent severe mental health distress and have them hospitalized rather than arrested against their will, if necessary, if they were in a severe enough crisis. There are a lot of people who think that that violates civil liberties. Is that program active? It sounds like maybe that would have been a third option in this case.

Elizabeth Kim: That is ongoing. I don't know what the scale of it is, but it is ongoing. The mayor says that the units have been able to remove thousands of people off the streets. The question that people have about the program is, once they do take someone off the streets and take them to a hospital, how long do they stay there? This is a program that really deserves a lot of scrutiny and study in terms of the longer-term impacts. What are the longer-term outcomes for the people who have contact with this program and are forcibly removed?

Brian Lehrer: More with WNYC's, Elizabeth Kim, and from Mayor Adams' Tuesday news conference right after this.

[music]

Brian Lehrer Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with our lead Eric Adams reporter WNYC and Gothamist, Elizabeth Kim, who usually joins us on Wednesdays after the Mayor's weekly Tuesday news conference.

Liz, I have to say, thinking about that last stretch of the show, it's that kind of thing that makes me feel so privileged to be able to host a show like this in New York City, where WNYC creates the space for people like all the callers that we had in that last stretch to have a complex conversation with the complexity that it deserves about complex issues like this and be constructive and look for solutions and share.

Certainly in the case of those last two callers, very personal, very difficult stories, and that they feel comfortable enough to do that. I'm just praising our institution here that there aren't a lot of media organizations or other outlets where I think this complexity exists. No, we're not doing a membership drive right now. I'm just saying I feel honored to be able to facilitate or help facilitate something that WNYC does that allows callers like those and conversations like those to come up.

Elizabeth Kim: 100%, Brian. I credit the callers and the conversations they have with us every week in informing the questions that I put to the mayor. When I ask him a question like, when I ride the subway, I'm not seeing a lot of engagement between police and homeless individuals, that's also because callers have called in and said that to us.

Brian Lehrer: You also asked the mayor if he would consider riding the subways to work at City Hall routinely like Mayor Bloomberg once upon a time did. Listeners, here's Liz question on that.

Elizabeth Kim: I know you talk to Mayor Bloomberg quite a bit. I'm wondering if the two of you have ever discussed riding the subways every day to work because that was something that he did. I think it was very popular with New Yorkers. It was a very popular gesture that he was riding to work the same way so many other New Yorkers do. I thought the fact that congestion pricing is coming up, it would be a very powerful example to New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: Here's the mayor's response.

Mayor Adams: Listen, I love riding the subway, I enjoy it a lot. Not only do I do it during the daytime, I'm out there 1:00 AM, 2:00 AM, 3:00 AM. Not a lot of mayors do that. When you look in my schedule, those of you who follow my schedule, if some of you have to follow my schedule, you need a whole two days off to sleep because my schedule is so full. I'm all over the City, half an hour interviews on my places.

If I could do it or I'm taking the subway to all those locations, I would love to. Every half an hour, my team, Gladys Miranda, who handles all of this stuff, I'm constantly engaging with New Yorkers, moving throughout the City, and it's a very full, full schedule. I got to be realistic, not only idealistic.

Brian Lehrer: Fair enough Liz, or what were you getting at there?

Elizabeth Kim: Riding the subways is arguably a pretty easy PR win for mayors. Like I said in the question to the mayor when Mayor Bloomberg did it, it was very well received. He caught some flack for riding in his chauffeured SUV to an express station on the Upper East Side before heading to City Hall. Overall, New Yorkers like seeing their mayor on the subways, and that goes for all mayors. I was also thinking that for Adams, it's about showing faith in the subway system at a time when we've been talking about this. New Yorkers are rattled by high profile crime in the subways.

There is a perception among some people that the subway is dangerous. This would be a powerful gesture. Also in that question, I pointed out that there's another reason. It would demonstrate how invested the mayor is in transit policies, arguably transformative transit policies like congestion pricing. I'll remind listeners that when Bloomberg pledged to ride the subways, he did so because he said he wanted to do his part to alleviate congestion. Adams now has the same opportunity.

Brian Lehrer: Bloomberg, the richest man in New York riding the subways to work. Was it a little performative compared to the irregularly scheduled time the mayor says he rides middle of the night, whatever, if he was telling the truth there?

Elizabeth Kim: Absolutely. That's the irony there, but maybe it's not ironic. Bloomberg felt he needed to project to this image of being more relatable more than Mayor Adams who's a former transit cop. He's described himself as the City's first working-class mayor. I would, again, say that in speaking to political experts, this is an easy PR win for him if he would be willing to do it. He said in his response that he has a very full schedule and he can't do it.

The idea, though, is if it's somehow built into his routine, I don't think people expect him to take the subway every day. If it was somehow built into his routine, just getting to City Hall, some people would argue that it's faster to get to City Hall from where he is than taking an SUV. It's not just the subways, it's mass transit in general. There was a lot of hope and expectation from transit advocates as Eric Adams was entering office that he would be this mayor of mass transit.

Brian Lehrer: The bus mayor.

Elizabeth Kim: He was given a jacket because when he pledged that he would build out bus lanes faster than any other mayor, they gave him a jacket that said "bus mayor." Then he did that ride on the City bike. I think he did it more than one time. Then he pledged to be the City's first bike mayor. This is also about him living up to some campaign promises.

Brian Lehrer: This was an image issue with de Blasio who maybe comes out the lowest of the three in this precise regard taking the chauffeured Limousine from Gracie Mansion on the Upper East Side to his gym in Brooklyn. He couldn't join a gym on the Upper East Side, and I get it. He liked the community that he had there, and he's a human being, and he had people he knew there, but I think he probably comes out the lowest of the recent three in image terms anyway in this regard.

Elizabeth Kim: I will give the mayor credit. It is true. He does take the subway in the wee hours of the night. A lot of that is about him monitoring and watching the NYPD, and how they're interacting, and how they're patrolling the subways. I will say I've even seen the mayor myself. I've run into him at Union Square with NYPD.

Brian Lehrer: WNYC and Gothamist, Elizabeth Kim, we're going to leave it there. There are other things from yesterday's news conference that we could have gotten to if we had more time, but we did have that long stretch on the subways, and policing, and social work outreach, and all of that at the beginning, which I think was worth it. Maybe we'll catch up on some of those other stories we were going to talk about when the mayor holds another news conference as we think he will next Tuesday and as you probably come on the show next Wednesday as we think you will. Liz, thanks for today.

Elizabeth Kim: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.