Reporters Ask the Mayor: Subway Safety, Dissatisfaction and A New Lawsuit

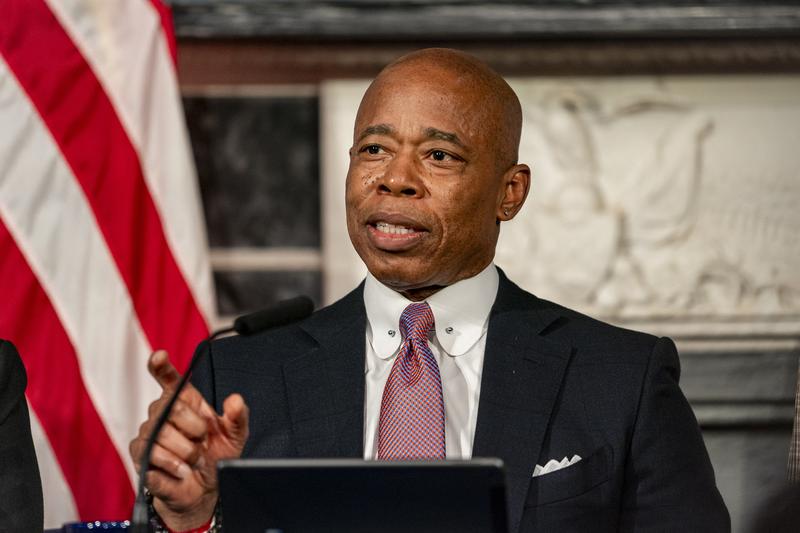

( Peter K. Afriyie / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, as usual, on Wednesday mornings after Mayor Adams's Tuesday news conferences, our lead Eric Adams's reporter, Liz Kim, joins us with excerpts and analysis and to take your calls. Subway safety, a right to shelter, a settlement on that with the Legal Aid Society regarding migrants and New Yorkers already here, very much in the news that just happened a couple of days ago, the sexual assault lawsuit filed against the mayor for an alleged assault in the early 1990s. This morning there's a new survey out showing a lot of dissatisfaction among New Yorkers with the quality of life right now. Hi, Liz. Thanks for coming on as always.

Liz Kim: Good morning, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start with subway safety and the recent deployment of more police and the National Guard. Listeners, here's a very specific question that Liz herself asked the mayor.

Liz Kim: Something that I've seen, and I also hear a lot from New Yorkers when they talk about taking the trains, we're seeing the police officers on the platforms, but not so much riding trains. What's the reason for that? Is there a way to incentivize them to ride? Because I think that a lot of New Yorkers say that that might actually give them the biggest reassurance because sometimes the things that make them nervous or things that are happening on the train while they're riding, while they're stuck there.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, I don't know if you got that question from our listeners, but we've been doing a number of segments on subway safety recently, and these deployments of police and National Guard and bag searches, and that question always comes up, what are they doing on the platforms? Why aren't they on the trains? Here's the mayor's response.

Mayor Eric Adams: Patrolling the complex underground of this subway system is a science. Your ability to respond when incidents happen and when you want police officers on the train and off the train, when you want them at platforms, at strategic location, there's a real science to it. If you have a police officer on the train during a rush hour, a packed train during the rush hour, that becomes extremely challenging to have that officer being able to walk up and down the train.

During what's called AP hours, 8:00 PM to 4:00 AM, less people on, you want those officers on the train, moving through the train, giving that visible omnipresence. What Chief Kemper does is with Chief LiPetri, they do an analysis, where are all crimes taking place and what time are they taking place. Based on that, they could deploy officers at the right place, at the right time, and the right type of assignment.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, there were many words in that answer, and obviously he was speaking as a manager of a complex system, policing in general, policing in the subway system. What did you take away from it?

Liz Kim: The first thing I'd point out, Brian, is the mayor really seems to relish these kinds of questions, specifically questions, not just on public safety, but about public safety on the subway, because as a former transit police officer, this is very much in his wheelhouse. Yes, he gave a very detailed answer. What I think, and I think maybe your listeners might feel the same way is the answer still left me a little puzzled. Yes, he makes a very good point. You don't want police officers to be stuck on trains. Commuters don't want to be stuck on trains, but if the police are not riding the trains during rush hour, how are they achieving this so-called feeling of omnipresence that the mayor wants?

He's saying that it is a science, and they are looking at the data and trying to see where are the crimes taking place. That's one thing, but I'm interested in hearing how you and listeners feel about that. That was the explanation, is that we're not seeing the officers on the train as much because they're not riding the trains at the peak times that the other New Yorker riders are.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you hear the question from Liz, and we talked about this on yesterday's show too, but feel free to continue. Do you want more police officers on the actual trains and including at rush hour? 212-433-WNYC, 433-9692. We know a uniform makes some people more comfortable, makes some people feel more threatened, so how about for you? The mayor did refer specifically to that horrible incident that had people so scared, and in which somebody did get shot--

Liz Kim: Which happened during rush hour, I would point out.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I was just going to say that too. During rush hour on an A train in Brooklyn. Here's the mayor on that.

Mayor Eric Adams: I hated seeing that shooting where people were afraid and had to duck. I could only imagine the next day that people picking up the paper and reading that that happens, that damages everything that we have done. We have a safe system. We have the safe city. We are the safest big city in America, and I'm not going to allow high-profile incidents to hijack the success of the men and women who have put themselves on the line every day.

Brian Lehrer: Why'd you pull that clip? What was interesting to you about that? He obviously wants the perception not to overtake the reality. It seems to me he's defending the police officers. He says the men and women who put their lives on the line every day. Where was he going with that, as you heard it?

Liz Kim: Last week we were talking about the role perception is playing in the mayor's and the governor's strategy toward public safety on the subways. Yesterday the mayor really actually tried to rely a lot on data. Now, prior, at the start of the press conference, he put up a chart that measured homicides in major cities. It turns out that New York City has the lowest homicides per capita. He's using that to say what mayors before him have said, which is New York City is the safest big city in America.

Then again, we had this very high-profile shooting. The altercation was captured on video. On video, you see not only the altercation, but you also see and you can hear the response of other riders, and it's very jarring. It's very disturbing. You hear people say, "Oh, my God." At one point there's a woman who you can hear saying, "Where is the police?" That's what the mayor is up against, but you hear his frustration there, "I hated seeing that". He doesn't want a moment like that to hijack what he feels is the day-to-day reality, which the data backs up. He says six felonies a day, 4 out of 4 million riders a day.

Brian Lehrer: Listener texts, great question, I don't feel as endangered on subway platforms because I have more space to move, inside the train I am a captive audience. Nicole in Brooklyn might feel differently. Nicole, you're on WNYC. Hello?

Nicole: Hi, can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Nicole: Great. Thanks. I'm a lifelong New Yorker. I'm in my 50s, so I've been here a long time. I ride the subway. I probably take 5 to 10 subways a day, almost five to six days a week. I'm not a big fan of this mayor for a lot of other reasons, but I do think there's an exaggerated narrative going around about the subways and how dangerous they are. I see more cops on the subway platforms checking inside cars than I've ever seen in my entire life here.

The city is relatively safe. I grew up here in the '70s and '80s. I don't think it's comparable. I'm wondering where this narrative is coming from because I don't feel unsafe as a small female traveling all over the place. I cannot say that I feel unsafe, and that's not to say there's not other problems with the mayor, but I'm not understanding-- That's not to say there's no crime, but I just don't understand where this obsession with this is coming from.

Brian Lehrer: Nicole, thank you very much. Here's the text message that says, my morning train paused in a station for an extended period this morning "to be checked by police." I guess that was the announcement. I assume this is part of the new policies and it annoyed the heck out of me to be delayed, especially when they'd already announced we had an officer available on the train. I think Steve in Manhattan might have a similar story to that texter. Hi Steve, you're on WNYC.

Steve: Hi. I was riding the train yesterday afternoon and there was an announcement made-- No, I just heard the last text he played so I guess this is unusual. First time I ever heard it. "If you have need of assistance or you want to speak to a police officer, there is a police officer available here at this station. Step forward, step out of the car, and let us know if you need attention." Now I got off the train because I thought it meant that there was a problem on the train and it was going to be stuck there forever. It was just like a public service announcement. I'd never heard of it before.

Brian Lehrer: Right. A general public service announcement. Steve, thank you. Something's new in that respect. Liz, I think I mentioned when you were on last week that I was on an A train recently, and heard an announcement that said, "There is a police officer on board and will be patrolling this train." I was surprised after hearing that on an A train that the mayor's response to your question wasn't more like, "We're doing that."

Liz Kim: Right. That's very interesting. To Stephen's remark, that PA announcement has been playing for some time. Maybe it was phrased differently when he heard it yesterday. I ride the trains almost every day and I've been hearing that for, I feel, several months, where you will hear the conductors say as we're riding into Union Square and also Times Square, "If you need assistance, there are police officers at this station."

I also wanted to address Nicole's remarks about she's this longtime New Yorker and the level of crime doesn't compare to what it was in the 1980s. That's true. I think we should keep in mind that there are a lot of new New Yorkers who haven't lived in New York City all their lives or even since the 1980s. What they're probably remembering is pre-pandemic. They're thinking about 2019 when crime was at historic lows. That is the perspective here is, what is it relative to?

Brian Lehrer: All right. We could talk about this all day, as evidenced by our caller board and the way text messages are streaming in. We had so many calls and texts on this when this was our topic for about 45 minutes at the beginning of yesterday's show. This is only one of the things that we want to talk about with respect to yesterday's news conference by Mayor Adams. When we continue in a minute with WNYC's Elizabeth Kim, We'll see how they address the sexual assault lawsuit that's now been filed against the mayor. Stay with us.

[music]

My Brian Lehrer on WNYC with our reporter Elizabeth Kim who covers the mayor's weekly Tuesday news conferences. I said we were going to go on to things other than deployment of police officers on trains, but it looks like we have an officer calling in with a reason that they're not deployed more within the train cars themselves. Let's hear what he has to say. Daryl in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. We appreciate you calling in.

Daryl: Thank you, Brian. I've called you in once before on these kind of issues. One of the reasons that officers are not always deployed on trains is because the train crosses multiple precincts, jurisdictions, in the course of its travel, those officers aren't always assigned. These officers are being taken from local commands or local transit districts in order to be placed on those platforms. Let's say you have a condition that's going on in Brooklyn, that officer, if he affects an arrest or he takes some kind of criminal action, he's pretty much tied to that particular zone that he's assigned to.

Brian Lehrer: That's interesting. We had another officer, I think a retired officer, calling in recently and said, "Bring back the transit police as a discrete force." I think in part, exactly so that this doesn't become a problem if you're assigned to the 77th Precinct in Brooklyn or the 34th Precinct in upper Manhattan and the train's going everywhere, you're out of your precinct, well that's a bureaucratic distinction, not a public safety one, right?

Daryl: Well, it becomes a manpower issue just because now you're-- on the short term, you're losing that officer. If he's on a train, you're losing that officer, his coverage for that particular zone or for that particular area when something does happen. To the mayor's credit, he says when you have these officers on platforms, they are there to address specific conditions. To be on a train, he's not there to address that specific condition that's in that particular place, he's now moved to a place where maybe that condition doesn't need to be addressed at all. [unintelligible 00:16:34] [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: A role in place where nothing is necessarily happening. Daryl, thank you. Keep calling us. I appreciate your input. Liz, anything briefly on that?

Liz Kim: No. I think that was very helpful. One thing I have wondered was I wondered why the officers couldn't just ride one stop and then walk to the other side of the platform and then get on a train going the other way and keep doing that. I understand they need to stay within their precinct or zone, but I guess one question is why not take a very, very short ride and then just maybe keep doing it several times again to show the riders that you're present inside the trains?

Brian Lehrer: All right. Let's go on to that next big topic. The sexual assault lawsuit filed against the mayor just recently for an alleged incident from the '90s when he was a police officer. This is being brought now because of the temporary so-called look-back window that suspended the statute of limitations for such allegations that the state had opened recently. What's the claim and what's the mayor's defense?

Liz Kim: The claim was initially filed in November, but there were not a lot of details. It was just the summons, and the person filing it wasn't required to provide those details. They probably wanted just to get the lawsuit in before the end of the deadline. What happened on Monday was the person did file a much more detailed complaint and the mayor was asked about it at his press conference. Essentially just to give you a summary, the accuser was someone who worked as an administrative aide in the Transit Police Bureau, working there around the same time as Adams.

She says that she had been passed over for a promotion, and she also claims that Adams offered to help her, but in exchange demanded oral sex. She says that when she refused, he forced her to touch his genitals. That is the essence of the complaint. The mayor was asked about it yesterday and just like he did in November, he adamantly denied that this ever happened and he said that he does not recall ever meeting this person.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. Did you want to go further on that?

Liz Kim: No. I was going to say that it was interesting because during the press conference, a lot of the questions actually focused not on the details of the complaint itself, but how the mayor is choosing to represent himself. The city's Corporation Counsel is defending the mayor in this case, and that essentially means that taxpayers are footing the mayor's legal bills on something that happened that preceded him becoming mayor, but also involves alleged personal conduct.

The mayor and the city's Corporation Counsel Sylvia Hinds-Radix, who was there at the press conference fielded this question, I think it must have been at least three times, is this right?

Brian Lehrer: Here's one of her answers.

Sylvia Hinds-Radix: The Corporation Counsel has based on the law and the charter the ability to evaluate and make the determinations. The same determination we make with other cases.

Brian Lehrer: Does that mean that she determined that the mayor was being accused of committing a sexual assault in his official capacity as a police officer as opposed to as a private citizen?

Liz Kim: She didn't go into detail, but she did say that the mayor being a former transit police officer is entitled to counsel here from the city. Then she was pressed on it because a reporter pointed out that there is a city statute that says Corporation Counsel can only represent employees within the scope of their employment. That's when she gives that answer that basically says, listen, this is my discretion and I decide that this is something that the city can defend the mayor on.

I think taxpayers might be uncomfortable with this. I reached out and I called John Kaehny. He heads Reinvent Albany. It's a good government group and he gave me what I thought was sort of a reasonable answer. If you think about the alternative. What's the alternative here? If the Mayor doesn't have the money to hire a private attorney and spend a lot of time and money on this case, he would have to set up what's known as a legal defense fund. He'd have to spend time also raising money for that fund.

That takes the mayor and also New Yorkers into possibly troubling territory because it opens up this situation where the mayor will be possibly inviting donors to give him something in exchange for something. What John Kaehny told me that he'd rather taxpayers just foot the bill for this. If you think about it. The cost relative to the size of a $100 billion budget. It's a very, very tiny fraction, but it's better than the risk, which is the risk to democracy.

Brian Lehrer: Let's go on to another topic. This settlement between the city and the Legal Aid Society over the right to shelter law as it applies to recent asylum seekers. Here's 17 seconds of the mayor on that from the news conference yesterday.

Mayor Eric Adams: The system was never built for people to come anywhere on the globe, stay here for as long as they want on taxpayers' dollars. We want to incentivize people like we've done over 60%. Over 60% of those who have come through our care are now self-sustaining.

Brian Lehrer: Can you describe the settlement, and Liz, I know you've covered dissatisfaction with that settlement by some advocates for the homeless.

Liz Kim: Yes. The settlement essentially codifies a practice that the city has been using since around last September, and that is restricting the initial stay for migrant adults to only 30 days. Now, up until now, migrant adults have been able to reapply. What the settlement does is it gives the city the right to deny those extensions unless there are "extenuating circumstances." This is a significant rollback because if you think about what is unique about New York City's right-to-shelter policy, it's that it was applied to everyone. Massachusetts has a statewide right-to-shelter rule, but that applies only to families with children and pregnant women.

There are some cities like DC that have a right-to-shelter rule, but only applies when the temperature is below a certain number. Essentially, it erodes what made New York City's right to shelter so unique. In the fact that it was sweeping. The reason it's sweeping because it's driven by this principle that people shouldn't be living out on the streets. No one. Not a man, woman, or child should be sleeping out on the city streets. It's bad for them. It's also bad for New York City

Brian Lehrer: Liz, the conundrum is there are so many people coming and there are only so many shelter slots and communities around the city are resistant to opening more shelters around the city so that's an issue. The mayor points out, certainly the financial pressure on the city to keep housing more and more and more and more people who are arriving indefinitely.

Then on the other side, the mayor boasted at the news conference, "We don't have people living on the street in New York City and we will not have people living on the street in Eric Adams's New York." If the policy is really changing and some of these adults without children are turned away after 30 days in a shelter and they don't have anywhere to go, he said that's about 80% of them are finding other places to go, but that still leaves 20% and that's thousands of people. What does he think is going to happen?

Liz Kim: That's exactly right, Brian. That is why there are advocates that are very critical of this deal because they say that even when the city started imposing this 30-day shelter limit-- I will say there is a 60-day shelter limit for families. This is being imposed across the board, but advocates say that once the city started imposing that limit, they did see more people being forced to stay out on the streets. I think that there is anecdotal evidence of that as well. Now that this is now enshrined and now that the barrier to reenter shelter is much higher, that is what critics of the deal say that that's what's going to happen as we head into the spring and there's expected to be a surge and we will see this play out.

I will say you're right Brian. It is a conundrum. One of the words that the Deputy Mayor Anne Williams-Isom uses, which I think is a good word, is that this is a crisis, it's a humanitarian crisis, it's an immigration issue, and because we have a limited amount of space, what do we do? We have to triage the situation. I think that that is an appropriate word because if there's a limited amount of space, they have to decide who gets that space. They are putting families and children at the top of that list.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, last question for this week. I see that you are looking at the front page of the New York Post today. Which is a picture, a caricature of Mayor Adams, or a photo of his face inside a caricatured body sitting in a room that's on fire with the sarcastic headline, 'This is fine.' This is based on a new survey apparently that finds just 30% of New Yorkers say the quality of life is good here. I will look with some skepticism at a New York Post cover on something like this, but why did you flag it?

Liz Kim: It's important because, for the most part, the Post has been generally friendly to the mayor. It's been a friendly outlet. They're aligned in terms of their priorities on public safety, but that was probably the harshest cover and it's a cover. It's not a single story that I've seen them do on the mayor. For people who are political reporters, it just makes you wonder whether the Post is beginning to turn on the mayor.

Brian Lehrer: Elizabeth Kim, covers city hall for WNYC and Gothamist. Since the mayor generally only takes reporters' questions about a variety of topics on Tuesdays, Liz generally comes on with us on Wednesdays with clips and her analysis and to take your calls. Liz, thanks for today.

Liz Kim: Thanks, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.