Remnick on Rushdie

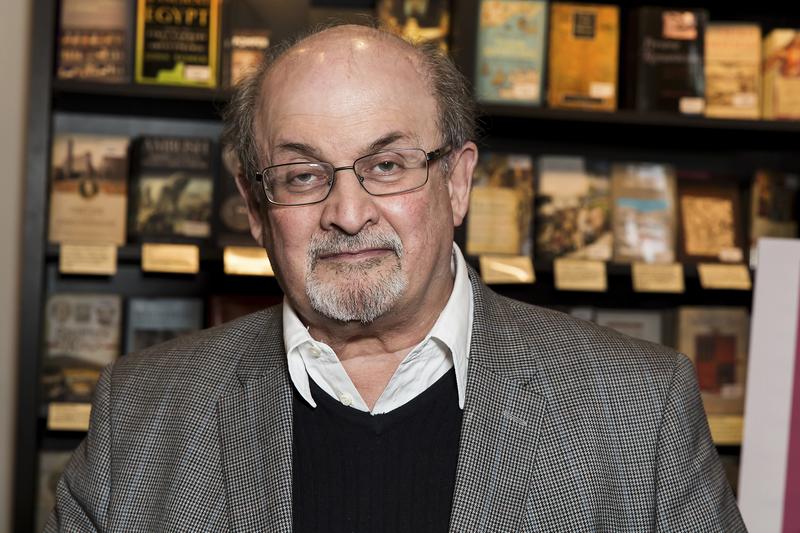

( Grant Pollard/Invision / Associated Press )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. We usually end the show these days with a call in for different groups of you to say something about your lived experience. Today, we flipped it around. We just had that call in for Afro-Latino listeners, and we had a call all in for doctors earlier in the show. We're going to end today with the lived experience of one human being, but a very famous one, famous both for being a great chronicler of the human condition and for being the victim of sectarian extremism.

Maybe you've even guessed already, even if you didn't hear me promote it earlier that it's the writer Salman Rushdie who was put under a fatwa, a death sentence by Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini back in 1989 for writing a novel, The Satanic Verses, that Khomeini considered blasphemous. As you probably know, Rushdie was attacked on stage last August during an appearance, stabbed multiple times for nearly 30 seconds before anyone stopped the attacker who apparently was trying to carry out the fatwa, though with no apparent connection to the Iranian government.

Well, now, Salman Rushdie is out with a new novel called Victory City, which deals with sectarian division as one of its themes, though the novel was completed before the attack he says. Salman Rushdie has been on this show multiple times, and we invited him on for a book interview not knowing how his recovery was going, but we were told he wouldn't be doing interviews for the book. Well, it turns out he did do one interview. It was with our friend and colleague David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker and host of The New Yorker Radio Hour here on WNYC.

This weekend's Radio Hour will be devoted entirely to the Rushdie interview. It's already out online, and we're delighted that David Remnick is joining us now to share some of it with us. David, always great when you come on, and welcome today under very special circumstances.

David Remnick: Great to be with you.

Brian Lehrer: Your conversation with Rushdie is deep and multilayered and wonderful, let me say. I'm glad he did this one interview with you. I listened to the whole hour as my break yesterday between the show and the State of the Union address.

[laughter]

David Remnick: Well, I'm honored. I'm honored always to be with you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Before we play some clips, I want to give you a chance to highlight something you and he emphasized, that he doesn't want to be known primarily as a victim or the subject of a fatwa. He wants to be known primarily as a writer, the writer Salman Rushdie. Has that been a struggle for him to keep that front and center in his public persona?

David Remnick: Well, the line that he has in the interview, which I think is apropos is, "I've always thought that my books are more interesting than I am and the world tends to disagree." I think the world for the last-- well, since 1989, Valentine's Day 1989, has been completely fascinated by, repulsed by, and all the rest, the fatwa levied against him, which is essentially a death sentence ordered by [crosstalk]--

Brian Lehrer: A head of state

David Remnick: A head of state and spiritual leader, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who probably issued that fatwa, so far as we know, without ever having read the book, according to his son, in fact, because he himself was in political trouble and could score some political points and maybe coalesce some support or regain some support after the terrible, prolonged war between Iran and Iraq, but that fatwa has shadowed not only Rushdie's life for for more than 30 years, but countless other people.

Translators were killed, bombs were put in bookstores, and it also presaged much that came after it. The rise of violent fundamentalism and the West's reaction to it, arguments about free speech that persist and that you featured on your program from time to time. The Rushdie affair in 1989, in some ways, was an affair that just didn't touch one writer, although it did immeasurably, but the entire world.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a clip from your interview in which he addresses something that he's had to guard against as a writer for being under this fatwa all these years and now actually attacked.

Salman Rushdie: There are various ways in which this event can destroy me as an artist. One way is that I should be scared and that I would write scared books or not write.

David Remnick: What's a scared book?

Salman Rushdie: Well, a book that doesn't tackle anything important, that shies away from things because you worry about how people will react to them. That's a scared book. A lot of them around these days. I'm too old for that.

Brian Lehrer: He said he could be tempted to write scared books, and conversely, he could be tempted to write vindictive books. By the way, I was struck by that little phrase that he tossed in there that there are a lot of scared books around these days. Did you pick that up? Did you have any idea what he was referring to?

David Remnick: I do. I think he thinks that one of the effects of the fatwa and its aftermath was a degree of self-censorship, at least among some writers, a hesitation about taking on topics like religion and politicized religion, but not only that. Now, it's hard to survey that, and I think certainly there have been many brave books published since 1989. I don't think Rushdie wants to be as categorical as all that, but I think he means to say, and I think I have this accurately, that there's a chilling effect any time an event like this happens.

It wasn't just that a fatwa was issued. There were many, many demonstrations at which the book was burned, effigies, that Rushdie himself was burned in effigy. Look at the lasting effect of the fatwa. Salman came to this this country and came to New York City 20 years ago and lived without guard, without hesitation. He lived so freely and was out so often that the New York Times and other places took it upon themselves to write stories about how he was a kind of fixture of New York social life. Some people even seem to find this repulsive, but Rushdie was determined to live almost flamboyantly as a free man.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I guess when you have to live as kind of an exile, I think you put it in your article that accompanies the piece, the long article in the New Yorker about Rushdie, live in exile, maybe when you decide you're not going to let yourself have to live that way or force yourself to have to live that way, the reaction to that, like a rebound relationship, is to live more flamboyantly than other people. Who knows? Rushdie talked about a period of time after the fatwa was issued when he had to deal with something you just referred to, a certain kind of backlash publicity that he was getting. Here's 30 seconds of him from your interview on that.

Salman Rushdie: Well, there was a moment when there was a me floating around that had been invented to show what a bad person I was.

David Remnick: How would you define the me, the Salman Rushdie that you're describing?

Salman Rushdie: Oh, you know, evil, arrogant, terrible writer, nobody would have read him if there hadn't been an attack against his book, et cetera. There was a false self that was floating around.

Brian Lehrer: David, I got the impression that false self and the idea that nobody would read him if he hadn't had the fatwa placed on him, that that didn't just come from Iranian extremists, right?

David Remnick: No, far from it. It's worth remembering that a lot of people behaved well, but a lot of people behaved disgracefully. What do I mean? A lot of friends and other people rallied around Rushdie. There's no question about that. Famous people and non-famous people, but a lot of people, including some famous writers, John Le Carre, sadly, among them, John Berger, Germaine Greer, Roald Dahl.

The now King of England was said to have at a dinner party remarked, "Well, you know, if you're going to write about something like that in such a way, what do you expect?" That's hardly a show of great sympathy. This is the then Prince of Wales, the now King of England. The British Foreign Secretary Jeffrey Howe spoke in a similar mode. Jimmy Carter, much to admire about Jimmy Carter, but Jimmy Carter wrote an op-ed piece in the New York Times criticizing Rushdie in the aftermath of the fatwa-

Brian Lehrer: How about that?

David Remnick: - on the grounds that it insulted someone's religion and one should expect backlash. In his piece, Carter said, "Well, Martin Scorsese made The Last Temptation of Christ and I was insulted." To which I would answer, "Okay, you may be insulted, but you don't have a right not to be insulted." The Pope did not issue a death threat or an edict of execution against Martin Scorsese. That's an immense difference.

Brian Lehrer: You call Rushdie's new book Victory City extraordinary. What makes it extraordinary for you?

David Remnick: Well, look, I think when all is said and done, the books that will be most lasting of Rushdie, I say, this as one reader, just one reader, is that without a question Midnight's Children, Shame, The Satanic Verses, Haroun and the Sea of Stories. I think some of the more recent novels have gotten more heavily criticized. I found this novel Victory City immensely enjoyable, and has nothing to do with what we've been talking about. Victory City is a kind of fable about South India in medieval times. It's a magical story.

Again, I'm a reporter in this case, I'm not a literary critic, but I found it enormously enjoyable, to greatly be recommended, but your readers will pick it up and see what they think.

Brian Lehrer: When you were talking about the new novel Victory City with Rushdie, he was describing how it was about, in part, sectarianism in a long-ago era in the history of South India and what I might call weaponized nostalgia, and that that seems to apply to the United States today. Here's that part.

Salman Rushdie: America talking about being great again. I want to know when was that. What was the date? It was obviously before the Civil Rights Act. Was it before women had the vote? Was it when there was still slavery? What are we harking back to? A fantasy past becomes a way of justifying bad behavior today.

Brian Lehrer: David, can you give us more there on that theme?

David Remnick: Well, obviously, in the American context, he's talking about Trump and MAGA and Make America Great Again and all that stuff. In an Indian context, right now, you have a government, the Modi government, which is immensely more popular than Trump ever was, which makes Modi's staying power and potential danger even more perilous than Trump if that can be imagined. Part of the ideology of Modi is Hindu supremacism, and very anti-Muslim.

Therefore, the rewritten version of history is, to put it crudely, Hindu good, Muslim bad. In this book, in Victory City, in fact, you see the struggle between a multicultural ideal and sectarianism. You also see the triumph of anti-patriarchal figures. The rights of women in this medieval imagined city are far greater than you might have expected. There is political content to this magical story. It's quite something.

Brian Lehrer: Now, to respect Rushdie's desire to be known first still for his writing, you delayed this part of the way you edited the interview until later on, and I've delayed asking you the obvious first question until now. You did this interview in person. How is he?

David Remnick: It's the first question I asked him in fairness when he walked in the door. We met at the office of his agent Andrew Wiley. He lost 40 pounds, although he does not recommend getting stabbed 15 times as a weight-loss method. The attack in his words was colossal. There was injuries to his liver. He lost the sight in one eye. Use of his left hand is not what he'd like it to be. There's scar tissue all over his neck and face. If he had been stabbed a quarter of an inch deeper, for example, in his neck, his carotid artery would've been hit and he would've bled out right there on the stage.

As it is, it's crazy to say this in some way, but he was very lucky. He's very lucky. A young guy for 20 seconds, whatever it was, stabbing away furiously had his way with him until he was pulled off. The injuries were terrible, and he almost died. It's an amazing thing that he didn't. A guy of 75 years old, both the psychological and the physical trauma of this is profound. You ask, how is he doing? Better than he might have any right to expect. He'll survive. He was himself. I've known him for quite a long time. He was funny in the interview. We spoke for three hours.

Brian Lehrer: Not only funny, but one of the things that really struck me in the interview was how much he laughed. Did you notice that?

David Remnick: Yes. Well, Brian, I'm a funny guy too, so maybe he was laughing-- [laughs] We had a good time. He doesn't want to do a lot of interviews, but I think he was eager to talk after all this time. We followed up, I saw him at the photo session for an hour or two, whatever that was, we chatted, and then we picked it up on Zoom. We talked a lot. He's not a perfect human being. Nobody is. He doesn't pretend to be, but I think he's a remarkable human being, and his resilience and his sense of defiance and his sense of dedication to what he's all about, as a writer of fiction, just can't be gainsaid, can't be praised enough.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you can hear the full interview on The New Yorker Radio Hour. I guess not the full interview. You just said you talked to him for three hours. Is that what you said?

David Remnick: The interview that we recorded initially was three hours. There was even more interview later. David Krass now, great executive producer, edited the three-hour interview to the hour that you'll get. That's up online now, and I think it'll be broadcast on The Radio Hour on WNYC on Saturday morning.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Saturday at 10 o'clock on 93.9 FM. I will also recommend you all to David's profile of Salman Rushdie in print in The New Yorker which is out already. Really in-depth piece. I noticed on my computer it displays at 46 pages, so [chuckles] you really went there.

David Remnick: Well, maybe you have big print.

Brian Lehrer: That must be it.

David Remnick: It's [unintelligible 00:17:38] [crosstalk].

Brian Lehrer: Wonderful work, David. Thank you for sharing it with us.

David Remnick: Always a pleasure, Brian. Take care.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.