Redistricting, Gerrymandering and the Midterms

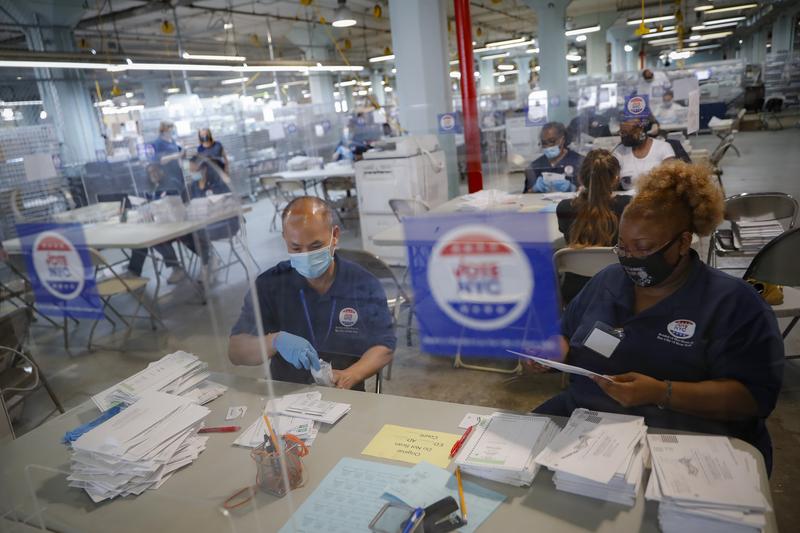

( John Minchillo / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Yesterday, we talked about the New York State Court of Appeals ruling that throughout the state's new Congressional district maps as a power grab by the Democrats. The map which states make once per decade after the census was made by the Democratic state legislature in New York, and would have likely cost Republicans three or four seats in Congress. Maybe Nicole Malliotakis, the only Republican member of Congress from New York City, as more of Brooklyn would have been added to that district, and a few more upstate, perhaps the difference for who controls the House of Representatives next year.

Whether Nancy Pelosi or Kevin McCarthy is speaker could be determined by district lines in Brooklyn and the Hudson Valley. Yesterday, we discussed implications for New York's primary election now likely to be split into two, most notably with voting for governor in June, for Congress in August, so they have time to redraw these lines. Today, we'll look more at the national implications with David Wasserman from The Cook Political Report, who is such an expert on these issues saw into this particular aspect of democracy that his Twitter handle is @Redistrict. One of those tweets, by the way, from after this court ruling, he wrote, "It's permissible to brazenly gerrymander in some states mostly red, but not others mostly blue." David, thanks a lot for coming on. Welcome back to WNYC.

David Wasserman: Thanks so much for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Can we start with that tweet? Why do you say it's permissible to brazenly gerrymander in some states mostly red, but not others mostly blue?

David Wasserman: Well, it's just a fact that courts have enforced anti-gerrymandering criteria in New York, but they have not enforced similar language that was approved by voters via constitutional amendment in Ohio. It's unlikely to happen in Florida where Governor Ron DeSantis rammed through a plan that would have given Republicans just as many extra seats as the New York gerrymander would have given Democrats, four more seats for Republicans, and three fewer seats for Democrats.

When you add it all up, it creates an apples and oranges situation in the house where you have some voters whose districts are really brutally gerrymandered, and others who reside in states with more equitable processes that produce maps that reflect swings from election to election rather than lock in districts that are heavily red and blue.

Brian Lehrer: You singled out Florida and Ohio there. You said what's happening in Florida, where the redistricting aggressively pro-Republican, as many seats to be gained there, perhaps for the red team as New York would have gained for the blue team. Why do you single out Ohio? Tell us about Ohio.

David Wasserman: Yes. A couple of months ago, just for context, redistricting looked like it was a silver lining for Democrats in an otherwise really bleak election cycle for their party. It was because Democrats had aggressively gerrymandered New York, they had also done the same in Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and they had also gotten favorable court rulings from state courts striking down Republican gerrymanders in North Carolina and Pennsylvania. They had also benefited from some of the maps drawn in states with bipartisan redistricting commissions such as California and New Jersey, but then the tide began to change.

We saw a state judge in Maryland strike down Democrats' gerrymander there. In Ohio, which was probably the biggest change to my priors, we saw Republicans propose one map that was struck down by the state Supreme Court as an unconstitutional gerrymander back in January. Republicans came back and proposed a similar map, and then the state Supreme Court ruled last month that there wasn't enough time before the primary to hold a trial to determine the new map's constitutionality.

Elections are proceeding, the primary is happening in Ohio on Tuesday, with a map that could give Republicans as many as 13 out of the state's 15 districts despite the fact that Trump only won the state by 8 points in both 2016 and 2020. That looks to be a situation where Republicans have simply run out the clock, despite voters having approved a reform that would seem to prohibit what they drew.

Brian Lehrer: Wow. Is this less a matter of the politicians in the various states than the judges? It was the New York State Court of Appeals but throughout these district lines, a court of judges appointed by Democratic governors. Are the courts in these more Republican states, the ones you mentioned, also reviewing the new district lines for excessive gerrymandering, but the judges themselves don't seem as non-partisan? Is that a fair way to put it?

David Wasserman: Well, partisanship of the courts has taken on an outsized role in this decade. There's no doubt that Democrats wouldn't have got what they wanted in North Carolina or Pennsylvania, had they not won key state Supreme Court races that generated partisan democratic majorities on those state Supreme Courts. That's the only reason why the maps in those states are much more equitable to Democrats than they otherwise would be.

In Ohio, a red state, you actually did have an anti-gerrymandering majority by a four-three margin on the state Supreme Court. The moderate Republican Chief Justice there, Maureen O'Connor, has struck down Republican maps more than four times, and yet, Republicans appear to have simply run out the clock on legal challenges, at least for this election cycle, and Republicans could win a partisan majority on the Ohio Supreme Court in the next few years.

Then take the case of New York and Maryland where you do have in New York judges on the state's court of appeals that were entirely appointed by Democratic governors, but by a narrow margin, they rejected Democrats' gerrymander. If you've got some states where gerrymandering is permissible and others that aren't, you're never going to end up with a house that treats both parties' voters fair or equitably.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, your questions are welcome here, for David Wasserman from The Cook Political Report, Twitter handle @Redistrict, about the implications of the New York State Court of Appeals, ruling that throughout the latest Congressional maps from the Democratic state legislature, and what's happening or not happening in Florida and Ohio, and other redder states, and what the solutions to it are. We'll get to how we can get to a single standard in this country so the House of Representatives is actually representative. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Alan in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Alan.

Alan: Good morning. Let me turn off the speaker. I have some comments from a perspective of you tried to carry petitions for council back in the '90s when the primaries were still held in September, and all petitioning was done in the warmest months of the year. In 1993, it was called the hottest year since 1948. When I argued that it was unconstitutional to require the same number of signatures in that heat season when there were heat advisories, telling petition carriers and signers to stay home, the Court of Appeals panels to hear pre arguments for appeals of these election cases in August of '93.

It sounded very favorable to the argument, but the problem was that season did not allow for any appeals to go all the way through. There wasn't time before the primary or the election. The joke was routinely all of these appeals were never heard on the merits because there wasn't time to hear them moving every [inaudible 00:08:29]

Brian Lehrer: Alan, let me just try to be clear for our listeners, what you're raising here, the prospect of an August primary instead of June in New York State for these Congressional seats, is something that you're finding a threat to democracy?

Alan: Well, it would have been back in '93. 30 years later, climate change is worse. There'll be more heat advisory days when people are told don't go out so how do you find people to carry or sign petitions? Aside from the fact, many people are waiting vacation so it's going to guarantee in that respect, a lower turnout, and also fewer people contesting races. On top of that, if you split the primary between the governor and other state races in June, and only Congress at a special date, you're going to have fewer people showing up. Turnouts for primaries are generally only about 10%. You could have a 5% turnout in some of these races, and this is a totally undemocratic thing to do.

Brian Lehrer: Alan, thank you for your call. This is really to the local issue of when the primary would be scheduled with enough time to have the petition signatures that the caller was talking about with having to start from scratch now because of the court ruling. David, have you come across this in other states? Are there any best practices on this kind of thing, or is it unique?

David Wasserman: Well, first of all, it's not so easy to move a primary. We've seen multiple states move their primary date this year. Maryland moved it from June to July. It's not just as simple as changing a date on a calendar. You have to reopen the candidate filing period and the petitioning period to allow candidates to adjust for new district lines. You have to give election administrators the time necessary to reassign voters to districts to ensure that they're voting in the right district. These are time-consuming issues. One of the reasons why the US Supreme Court overruled lower courts in Alabama, the Republican map there was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

They said it's too close to the election to do anything about the lines that the Republican legislature passed, even though they might be discriminatory. Democrats in New York are hoping that federal courts overrule state courts and say, "Hey, it's too close to the primary to change the lines." By federal law, voters should be entitled to a June 20th primary. That's the last-ditch Hail Mary that Democrats are waging to try and rescue their gerrymander, and it's under what legal mavens would call the Purcell Principle but it's still doubtful that federal courts will let Democrats get their way here.

Brian Lehrer: I'm glad you brought that up because I didn't realize that was even still a final recourse for Democrats to appeal this highest state court ruling to a federal court and keep the Congressional lines that the Democrats drew. One of the problems here, one of the reasons we don't have a single standard around the country for how much gerrymandering is permissible, is that the Supreme Court refused in a recent case, to establish national standards for drawing district lines and said, "No, this is up to the states. You each decide on your own," right?

David Wasserman: That's right, and neither Congress nor the US Supreme Court has stepped in to establish any guardrails against this practice and the result is that it's basically become an arms race. Redistricting is existential to election outcomes. It has the power to predetermine outcomes well in advance of November. When you have partisans in control of the process in most states, you end up with districts that are very lopsided for one or the other. Parties don't like spending millions of dollars every two years trying to win competitive races when they could just put the district away with a stroke of a pen. What we're looking at nationally is decline of competitive districts by about a third and we can only see 30 to 40 districts out of 435 that are genuinely competitive heading into the fall.

Brian Lehrer: It's another reason for polarization in our politics, whether or not it accurately represents the amount of polarization in the actual public at large. We're going to continue this in a minute with David Wasserman from The Cook Political Report, Twitter handle @Redistrict. If it's so unbalanced right now, if the federal government refuses to do anything at the judicial level or at the legislative level in Congress to smooth things out so we have a single standard, if Republican courts seem more likely to allow partisan redistricting in red states than democratic appointed courts in blue states, making even more of an over-representation for Republicans in Congress, how do we get to a single standard? How do we make the House of Representatives truly representative? We'll look for some solutions with David Wasserman and more of your calls, right after this.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC with David Wasserman from The Cook Political Report on redistricting, as we've been talking about after the court of appeals in New York State throughout the gerrymandered pro-Democratic district lines. Let's do a little more history on this to let people understand just how unrepresentative the House of Representatives is right now. Take us back to the last national redistricting after the 2010 census. In the 2010 elections, Republicans did really well at the state level and won control of most state governments. How did that play out in terms of the subsequent redistricting for Congressional seats nationally?

David Wasserman: One of the reasons why it's hard to get much more Republican than the lines from the last decade is that Republicans had such an advantage in the last cycle. In 2010, Republicans picked up more than 600 state legislative seats and they had exclusive power over redistricting in almost five times as many districts as Democrats 219 to 44. What that produced was a set of maps on which Republicans multiple times lost the house popular vote or won fewer votes for house nationally than Democrats, but still won a majority in 2012 and 2016.

In fact, in 2016, the median house district if you were to rank order the presidential results by district from the bluest to the reddest, the median district, the 218th seat in the house was a district that voted for Donald Trump by three points, even though he lost the popular vote by two nationally. In other words, the median house seat was five points to the right of the nation as a whole. Now, because Democrats were successful in suing to overturn Republican-drawn maps in Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, and Pennsylvania in the last six years, that Republican skew went down somewhat.

In 2020, the median house seat was only two points to the right of the nation. Democrats thought that in this round, because of new commissions and lawsuits, they were going to be able to eliminate that skew entirely. In fact, many analysts said that would happen as recently as February, what we're finding out is that Republicans are probably going to gain three or four seats from this round of redistricting, because of recent developments in New York, Florida, and Ohio.

Brian Lehrer: Do you have the numbers on over-representation? In other words, if we've had a situation in the last 10 years where Republicans are statistically overrepresented in Congress, it's supposed to be the House of Representatives but maybe it's the House of Unrepresentatives, is the percentage of Republican-held seats X larger than the percentage of Americans who voted for Republicans? Do you have that number?

David Wasserman: In the last two elections, it was pretty well aligned actually. In 2018 Democrats won about 53% of House votes, and they won around 53% of seats. In 2020 it was 51 and 51. There tends to be a winner's bonus for whichever party is ahead and therefore winning the majority of the closest swing districts. This time around though, I do think Republicans could significantly outperform their share of the vote because they're likely to carry a lot of these competitive seats given how low President Biden's approval rating is. Even some districts that Democrats drew to be Biden plus 10 or Biden plus 12 districts could be at risk this fall.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a listener question via Twitter. Listener asked, "Don't some states have independent commissions to do redistricting? What's the track record there?" What would you say to that question?

David Wasserman: Yes. There are 10 states that employ independent or bipartisan commissions. The biggest ones are California, Michigan, Colorado, New Jersey, Washington State, Arizona. To be honest, they're not all built alike. California, Michigan and Colorado probably have the most independent commissions because they have components of independent or unaffiliated commissioners who are the grease to be able to make those processes work. Whereas in Arizona and New Jersey, and in Virginia, the commissioners are pretty much all Democrats and Republicans appointed by party leadership, and they come to these commissions with marching orders.

The results can be that one party's map gets selected by a tiebreaker and it tends to heavily favor one party or the other. This time Republicans seem to get the better end of the deal in Arizona, Democrats seem to get the better end of the deal in New Jersey and perhaps Michigan. Colorado was pretty much down the middle. It really depends on what the criteria are from state to state but some Commissions are more effective at taking politics out of the process than others.

Brian Lehrer: Since it was a independent redistricting commission failure in New York State that allowed the legislature to go ahead and draw its Democratic Party control lines anyway, and now it's somebody, a professor from Carnegie Mellon named [unintelligible 00:19:43] who the court has appointed to, I guess, solely as an individual, some outside hopefully neutral person going to draw the district lines for New York after this court ruling. Do you know him by any chance or his track record or if he would lean one way or another?

David Wasserman: This is, to my knowledge, the first time that he's been selected as the special master. Of course, it's not the first time a special master has been selected. 10 years ago, when there was an impasse in New York, keep in mind that this is the first redistricting cycle in the modern era when one party has had a supermajority in the legislature or in fact has controlled both houses, and it's the first time since New York passed a constitutional amendment curbing gerrymandering.

10 years ago when there was a split legislature, the federal court appointed a special master named Nate Persly who drew a map that was pretty compact and featured several highly competitive districts that flipped throughout the decade. It really didn't give one party much of an advantage over the other. If Jonathan's service from Carnegie Mellon takes the same or a similar approach, then we're looking at several competitive seats and Democrats could potentially end up with fewer seats than they have now which is quite a swing from the map they passed that would have given them an additional three.

Brian Lehrer: Few more minutes with David Wasserman from The Cook Political Report and Twitter handle @Redistrict, as we talk about the national ramifications from the Court of Appeal's ruling in New York State throwing out the Democratic favorable or favorable to Democrats Congressional district lines that the state legislature had drawn. If we have a state's rights system of gerrymandering or not, how can we ever get to real representation by a single set of best practices? Is there any path?

David Wasserman: It's hard to see one from here. Part of the issue is that power begets more power, right? Republicans are likely to benefit from this round of redistricting. They're already favored to take back control of the House, which with or without a favorable outcome in redistricting, they probably would have gotten. That means that they're not going to reform a system that has benefited them. Democrats had a narrow window of opportunity to pass something.

They put together an election reform package that was too broad for the entire party to be able to get behind. You had some members in the House like Benny Thompson from Mississippi who opposed moving to redistricting commissions because he was worried about the impact on Voting Rights Act districts, and, of course, you had Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema in the Senate who were reluctant to break the filibuster to pass an election reform bill.

It's very difficult for Democrats to achieve that and the Supreme Court has an even more conservative majority than the one that said, "We're not going to take this issue up." Partisan gerrymandering is non-justiciable in federal courts. We're really at an impasse when it comes to reform. It's been a piecemeal state-by-state movement but that's, of course, resulted in vast inequities between how states send representatives to Congress.

Brian Lehrer: Jude on Staten Island, you're on WNYC with David Wasserman. Hi, Jude.

Jude: Yes, hi, Brian, and hi, David. I'm really distressed by the court striking down of this gerrymander. You can call that the Democrat plan. In particular, Staten Island is often perceived as a white conservative district and it's really a misperception actually. We have a 40% population of people of color. In the '80s, I believe it was, the district was gerrymandered by the Republicans to include those neighborhoods of southern Brooklyn that are whiter and more conservative.

The Democrats' plan actually included more neighborhoods of color in Sunset Park and those areas of central Brooklyn. I'm not sure if it reaches the level and what the criteria is for a Voting Rights Act district, but by dismantling those new district lines, you could be seriously watering down the voting rights of the people of color including 40% of Staten Islanders who are people of color whose representation was actually obviously not clear by the way that it was Malliotakis and the Republicans got an upper hand.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting, Jude, thank you very much. David, that's another part, as you know, of the redistricting puzzle all over the country. The Voting Rights Act guarantees that there be a decent representation of minority voters by having concentrations of them in a fair number of districts. Every district in the country doesn't represent the ethnic majorities and leave out the ethnic minority. Where does that come into play with this?

David Wasserman: That's a great question. The definition of a Voting Rights Act district has been variable over the years depending on court's interpretation. Democrats and civil rights groups would like a broader definition of that term to mean that a minority group could work in concert with another group of voters as a coalition district to elect a candidate of choice. Conservatives have wanted to define a VRA district as one in which one minority group makes up a majority of the district's voting age population which is a higher threshold to meet and it looks like the US Supreme Court is headed towards narrowing that definition.

I've never heard the Staten Island district New York 11, I've never heard the case for that being a VRA district because there's no minority group that makes up a plurality of voters. It's a white majority district, whether it's been attached to Manhattan like it was back in the '70s or Brooklyn like it's been for the last four decades but the partisanship of the district is highly dependent on which part of Brooklyn it's attached to. Even though the Democratic map included diverse neighborhoods like Sunset Park, the reason why it was blue under the map that was struck down was white liberals in Park Slope and other neighborhoods.

Republicans would prefer to keep a similar configuration with the current plan that includes more conservative portions of South Brooklyn. It's hard to see how a special master-drawn map, a neutral map, would produce a pro-Biden district and so this ruling is really a lifeline to Nicole Malliotakis, the Republican incumbent.

Brian Lehrer: If you have time for one more caller. I think Patty in Princeton Junction is going to float an idea here that's like if we can't solve the representation problem by nonpartisan districting, maybe we can solve it by nonpartisan something else, right, Patty?

Patty: Yes. Thanks, Brian. Yes, that's precisely where you mentioned increasing polarization. It's not unheard of to have nonpartisan elections at the local level. Before we all jump in and say that that's not going to happen at the presidential level or even the state level, how about it?

Brian Lehrer: New Yorkers will remember that Michael Bloomberg when he was mayor tried to move the city toward nonpartisan elections where people just run as individuals, not as Democrats or Republicans and, of course, he's a famous centrist. Is that viable or a solution to anything even in theory, David? Then we're out of time.

David Wasserman: Well, first of all, Patty, great question. I grew up a mile from Princeton Junction. Moving towards more open primaries, I think, does hold some promise for reducing polarization. Several states including California, Washington, Alaska, Louisiana, they've moved towards jungle primary systems where every candidate regardless of party runs on the same primary ballot and the top two advance to the general election. In very lopsided districts that tends to give the minority party more power over who ultimately represents the seat.

In a perfect world, would we just wave a wand and take partisanship off the ballot entirely? I think that would make Washington work a lot better. Is that realistic as a reform given that most incumbents who make our laws rely on parties and partisanship? Probably not.

Brian Lehrer: David Wasserman, redistricting expert for The Cook Political Report. Thank you so much really, really informative.

David Wasserman: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Not encouraging but informative. Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.