WNYC's Supreme Court Pod More Perfect's New Season

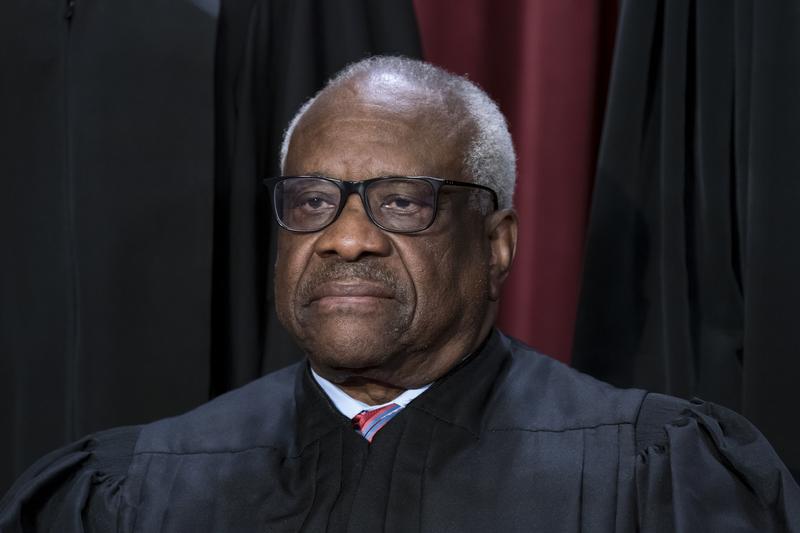

( J. Scott Applewhite, File / AP Photo )

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now we want to help introduce the new second season of the WNYC series called More Perfect. It's the podcast about the Supreme Court's most significant rulings and their impact today. Episode one was about the tension, historically, over when a person's religion could exempt them from the law. A Native American man who used the drug peyote for religious purposes, not exempt, but a web designer who refuses to be hired by gay couples for wedding-related websites? Well, that might be another story. We'll soon find out.

Episode two is just out today, and it's all about Clarence Thomas. Now, not so much the current corruption scandal over undisclosed big gifts from a Republican mega-donor that's been in the news a lot; more about what Justice Thomas actually believes, and the experiences in his life that led him to those beliefs, like attending Yale University.

Reporter: What was your favorite memory as a student at Yale?

Clarence Thomas: As far as my greatest moment -- there have been some singular moments that I did have at Yale. It was called graduation.

[laughter]

Clarence Thomas: I got out of that place, man.

Brian Lehrer: We'll talk to the host of More Perfect, WNYC's Julia Longoria in a minute. First, here's another excerpt. This one runs a little longer, a couple of minutes, from the new Clarence Thomas episode. This clip revolves around the idea that Justice Thomas, of all people, might have more in common with Malcolm X than you might think. This clip includes Julia and some experts on Thomas, and a voice from the past you will no doubt recognize. It starts by picking up on that notion we just heard, that Clarence Thomas got a rude awakening compared to his earlier education when he went to Yale.

Julia Longoria: Thomas was treated very differently at Yale than he was in Pinpoint, or at Seminary.

Female speaker: It was a different kind of racism, it was a much more subtle racism.

Malcolm X: I think there are many whites who act friendly toward Negroes.

Male speaker: One of the things that Malcolm X used to say, he made a distinction between the fox and the wolf.

Malcolm X: The wolf doesn't act friendly.

Male speaker: The wolf is scary, bares his teeth, is dangerous. You know what you're getting with the wolf.

Female speaker: The fox seems very different from the wolf.

Malcolm X: The fox acts friendly towards the lamb.

Male speaker: Not so scary, but is in the end just as lethal as the wolf.

Malcolm X: Usually, the fox is the one who ends up with the lamb chop on his plate.

Male speaker: Malcolm X used that analogy to explain two different kinds of white people. There's the white Southern racist, vicious, violent, overt.

Female speaker: Like the white woman who strut up to Clarence Thomas' grandfathers house and calls him, "Boy."

Male speaker: You know what you're getting with that kind of white person. Then there's a different kind of white person, who seems like what we call today your ally, seems like he or she cares about you, and for you, and is looking out for you, but is ultimately, like the fox, just as much your enemy.

Malcolm X: Their appetite is the same. Their motives are the same. It's only their mannerisms and methods that differ.

Male speaker: That person for Malcolm X is the liberal, the white liberal.

Female speaker: At Yale, Thomas sees foxes everywhere.

Brian Lehrer: That excerpt from the new episode, just out today, of More Perfect, the WNYC podcast about the Supreme Court and its most significant rulings. With me now, the host of More Perfect, WNYC's Julia Longoria. Hi, Julia. Welcome back to the show.

Julia Longoria: Hi, Brian. It's great to be here.

Brian Lehrer: Now, you and your team at More Perfect suggested that particular excerpt. What were you trying to show there?

Julia Longoria: I've watched Clarence Thomas on the court for a long time since I started working on the show, over five years ago. I always was like, "What's going on with him?" I guess I never looked deeper at what he was deciding. Often, he's voting with the white conservatives on the court, but he has his own reasons for it. We as a team were really surprised to learn that he had this background where he used to listen to Malcolm X on records in college.

You can see that Clarence Thomas and Malcolm X have quite a bit in common, this idea of the fox as a sort of more subtle racism, that might be more insidious, that's more dangerous. You can see how Clarence Thomas tries to fight against that kind of racism in his decisions, particularly in affirmative action decisions.

Brian Lehrer: Right, so how, for example? Let's explore this. Do you see that thinking reflected in Thomas' decision, maybe in the University of Michigan affirmative action case, or any other example you want to take?

Julia Longoria: Yes, in the affirmative action cases in Michigan from a while back. Affirmative action is back at the court this term, but back then he focused on, in his opinion, the idea of the white administrator of the University of Michigan as being given too much power to choose which Black people get to sit at the table with them. He sees that as foxes having this discretionary power to decide that sort of thing. He sees that as exploitative.

His point is if you really want to have more Black people sitting at the table, you need to address the structural issues, actually, he says, which is kind of surprising from Clarence Thomas. He says, "Let's get rid of the LSAT. The LSAT is part of the problem, these tests that are rigged against Black people, people without resources to take the tests." That affirmative action is a bit of a band-aid on a problem that has real solutions.

Brian Lehrer: That philosophy that you're describing there, he sees help for Black people in this country by the government, or institutions like The University of Michigan, or Yale as really a way of white elites maintaining their power. Are you clear on how he explains that, if the part of their power he's critiquing is only, it sounds like only the parts that explicitly help Black people?

Julia Longoria: It's complex and kind of hard to understand. I think we were interested in what he thinks he's doing, and it seems like his experience at Yale has some influence over how he thinks about this. I think what he believes is that if you accept this help from white people, then that help follows you everywhere. It's like as a person who accepted this help, your success is never yours. I think that's the idea.

Brian Lehrer: If he wants things to change structurally, and I don't know if you're going to know the answer to this question, I don't know if anybody does, but another way to look at state or private institutions help for Black people in this country is through a lens of reparations, right, that the state and the institutions stole labor and money from Black Americans for all these generations.

That's why we have a 9:1 white:Black wealth gap in this country, and so the state and private institutions that benefited from that plunder, owe a concrete debt to the people today living in relative deprivation because of those actions. I'm just curious if, in your reporting, Thomas ever got explicit about his views on that way of thinking.

Julia Longoria: From what we can tell, he's not for that either, so that's where his argument might fall apart, but no, I don't think that reparations are part of Clarence Thomas' idea for the solution. He sees it as Black people can help themselves. He had help, had gifts along the way that he doesn't acknowledge. There are definitely holes in the argument.

Brian Lehrer: Right, and I guess supporters of affirmative action argue, in some cases, that it's a form of reparations, because of all that deprivation.

In another case you cite, Thomas says, "Juries are racist." He uses that belief to endorse the idea of some mandatory death penalty formula that I think most racial justice advocates would abort. Can you explain his thinking on that?

Julia Longoria: Yes. The idea is-- He even quotes his predecessor, Thurgood Marshall, the liberal justice, and saying that juries are racist, giving them discretion is an invitation to discriminate. In his opinion, in the case we describe, he talks about how a mandatory death penalty scheme where if you're in a death penalty state, where a mandatory scheme would solve the problem of a jury's discretion. Just take the jury out of the equation is his logic.

By that logic, banning the death penalty would also fit that logic. He does point to a time when the Court struck down a mandatory death penalty scheme, and he thought the court was wrong about that.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. It's ironic because the main critique of the death penalty is that racist juries handed down more often for Black defendants who commit the same crimes as white defendants. Thomas realizes his philosophy. Many of his race-related rulings leave so many Black Americans thinking he's not on their side. You have a clip of him commenting on that. Here it is.

Clarence Thomas: It pains me deeply, more deeply than any of you can imagine, to be perceived by so many members of my race as doing them harm. All the sacrifice, all the long hours of preparation were to help not to hurt.

Brian Lehrer: It sounds earnest. What's the next thought there? He is pained by knowing so many people of his race think he's acting against their interests, but--?

Julia Longoria: But he continues to follow his philosophy down the road it's led him. [chuckles]

Brian Lehrer: Right. Thanks for a little preview of the new episode of More Perfect. Again, folks that is just out today. Do you want to back out for a minute and introduce listeners to the series more broadly, for people who don't know More Perfect yet?

Julia Longoria: Absolutely. More Perfect is a show from WNYC Studios. We tell stories at the Supreme Court. We tell stories of ordinary people's lives or the justices' lives, intersecting with some of the biggest stakes possible. We do radio documentaries, going deep into some of the biggest cases this term, and the cases from the past that are affecting us now.

We actually are in season four. We've relaunched after going dark for a while. We're at a moment when the Supreme Court is more unpopular with Americans than ever, and we're trying to make sense of this moment how we got here, and what are some of the biggest cases that are affecting our lives, spoken in a language a lot of us don't understand. We're translating them for listeners and bringing the human stories.

Brian Lehrer: The Clarence Thomas episode out today is episode two in this season. Episode one, as I mentioned in the intro, was about when the court says a person's religious beliefs can exempt them from the law. What was that case about using the illegal psychedelic drug peyote for religious reasons?

Julia Longoria: Yes. It was about a man named Al Smith. He was a Native American man who had a really remarkable life. We tell the story of how he was taken to boarding school as a kid, and separated from his traditions, and found them again. Yes, he ingested peyote as part of a Native American church ceremony. He was fired from his job actually as a drug and alcohol counselor, interestingly, and took his case all the way to the Supreme Court and lost.

That case, the moment it was decided, Scalia wrote the majority opinion, it was hugely unpopular. People on both sides of the political aisle across different religions wanted to overturn it immediately and never succeeded. The effort to overturn that case comes from actually people on the religious right, who want to say Al Smith should be able to sidestep a drug law, and they want to be able to sidestep anti-discrimination laws saying they don't want to provide their services to same-sex couples.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Going back and giving that Native American man or any ones in the future, the right to use an illegal drug in their religious ceremonies, because they want web designers or the particular web designer in this case and, I guess a lot of different kinds of business owners by extension, to be able to discriminate against same-sex couples who want their services for their weddings.

All right. We will see what happens with that decision, which is expected by the end of next month. More Perfect, in its latest season from WNYC, wherever you get your podcasts. The host, our Julia Longoria. Julia, it's awesome. Thanks for sharing.

Julia Longoria: Thanks so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.