The Post-Civil Rights Reality

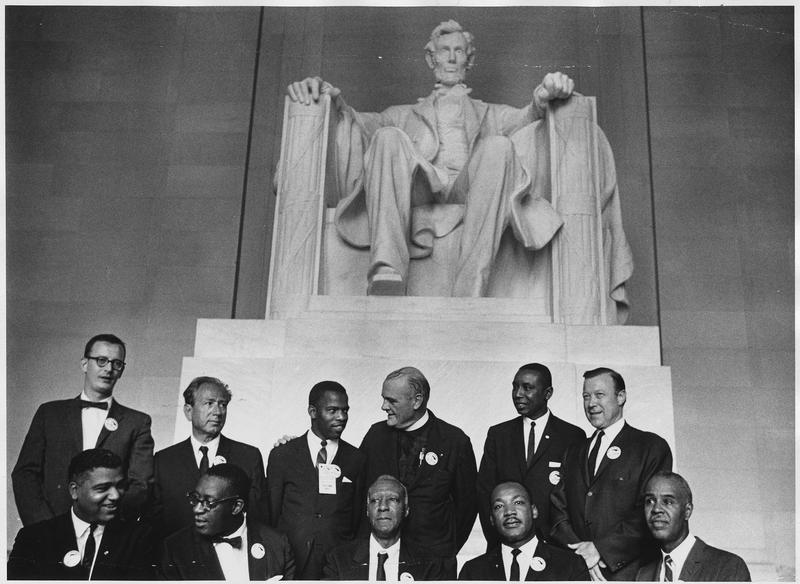

( National Archives )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. While we all remember Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s I Have a Dream speech, some of what's forgotten is that the marches on that day 60 years ago gathered to advocate for a number of economic policies like a national minimum wage and a federal jobs program to bring about racial and economic equity in the United States writ large.

While Dr. King spoke of an integrated future where children were not judged by the color of their skin, he understood that without addressing the economic oppression of Black America and other poor people, this dream could not be realized. In honor of the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington, experts at the Economic Policy Institute, the progressive think tank, released a report tying the march of back then to the economics of now.

This report is titled, Chasing the Dream of Equity: How Policy Has Shaped Economic Racial Disparities. It examines the connection between racial inequality and policy in the United States. It uncovers realities that we live in today such as that civil rights-era policies aimed at creating a more equitable society have, in many respects, failed to do so. Sadly, it provides policy suggestions that they feel are still necessary for today on how we can move towards that goal of economic equity here 60 years later.

In just a minute, we're going to talk to a writer of the report, Kyle Moore, economist with the Economic Policy Institute's Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy at EPI. First, just to give you a little example of how we're still tragically talking about some of the same things today, here's a clip of March Director A. Philip Randolph from that 1963 speech.

- Philip Randolph: Look for the enemies of Medicare, of higher minimum wages, of social security, of federal aid to education, and there you will find the enemy of the Negro, the coalition of Dixiecrats and reactionary Republicans that seek to dominate the Congress.

Brian Lehrer: A. Philip Randolph 60 years ago. Are we talking about the same thing still today? Yes. Kyle Moore, welcome to WNYC. Thank you for joining us today.

Kyle Moore: Hi, Brian. Great to be back on the show for sure. It's always great to hear the legend, A. Philip Randolph, true champion of civil rights and liberal rights.

Brian Lehrer: Absolutely. Remind us as a point of history, what exactly were the policies that marchers advocated for through the March on Washington that were economic in nature? Your report tying the march then to the economics of today lists them very specifically.

Kyle Moore: For sure. I want to be clear. I was not the lead author on this report. The lead author was my colleague, Adewale Maye. He did a great job pulling this report together. That March had a lot of specific economic demands that folks really don't keep in mind when they think about the march. They think the march was just about voting rights, right? There were some very specific economic demands here. Some of which were, again, a National Minimum Wage Act that would give all Americans a decent standard of living.

They were calling for $2 an hour at the time, which would be an equivalent to something like $19 an hour today. They wanted, again, comprehensive and effective civil rights legislation to guarantee all Americans' access to all public accommodations, decent housing, adequate and integrated education, and the right to vote. They wanted a broadened and more inclusive Fair Labor Standards Act that would include all areas of employment that were presently excluded.

They wanted a massive federal program to train and place unemployed workers. These are bold policies that they were pushing forward at the time. What they did, these are some of the greatest political economic minds of the time. They looked at the situation that Black people were in, looked at the history of the United States, and judged that the United States owed its Black citizens these things. These things would improve the living conditions and working conditions for all Americans. This is what they were pushing forward 50 years ago.

Brian Lehrer: People remember, of course, the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Coming after that, the Voting Rights Act of 1965. What about specific economic policies that may have been enacted that echoed or that reflected what the March on Washington was calling for?

Kyle Moore: Unfortunately, a lot of those demands, some were met, but they were met in faltering ways and not ways that were adequate to solve these problems going forward, which is why we see some of the disparities that we see today. The Fair Labor Standards Act was expanded to some extent and that did particularly benefit Black workers. There were expansions to the minimum wage. That, again, disproportionately did benefit Black workers at the time.

We definitely know, looking at the minimum wage today, that those increases in minimum wage haven't kept pace with either the increase in productivity that we've seen over time nor the increase in what's required for a decent standard of living, which is what they were pushing for at the time. We did see some movement on the minimum wage, but not enough. There still needs to be more. We saw some movement in putting forth policies like affirmative action that would encourage or require firms and businesses to do what they can to diversify their workforces.

That has been weekly enforced over the period, of course, struck down very recently in education. The pattern that we see here is that faltering progress is made when there is some political will to get something done. Then the subsequent few decades after that, folks are clawing at these policies, trying to defame them, trying to take down enforcement mechanisms that may exist, and trying to take away the funding for the support programs that folks might have put in place. It's a real struggle to move the needle on these policies.

Brian Lehrer: Your report lays out specifically what some of the existing racial economic disparities are today, 60 years later. I thought it would be useful for our listeners to go over some of those in particular because you get into wage gaps, wealth gaps, unionization gaps, homeownership rates. Do you want to just give some people some of the numbers on the particulars of even now 60 years after the March on Washington, 59 years after the Civil Rights Act, et cetera, et cetera, just how much racial economic disparity there is by the numbers?

Kyle Moore: For sure. One of the starkest indicators is the racial wealth gap, right? As of 2019, the typical median white household had eight times the wealth of the typical Black household. These are statistics that have been present for the entirety of the time that we've taken statistics on household wealth. Something similar can be said for unemployment rates. Right now, we're at a point where we have low unemployment rates across the board.

However, the ratio between the Black and white unemployment rate is still 2:1 essentially. It's been 2:1 certainly at the time that these demands were being made at the March on Washington, but that 2:1 ratio was pretty much kept consistent through recessions, through good economic times. It's a feature of the US labor market that still has to be dealt with. Homeownership is very rarely over 50% for Black homeowners.

That's been the case for, essentially, the entirety of the time that we've had statistics on homeownership rates. There are still wage gaps. There are gaps in life expectancy and morbidities. There is a very real extent to which the political-economic lives of Black and white people in this country are very different and have been different for a very long time. That's largely because we haven't really put in place the strongly enforced bold policies that will be necessary to actually move the needle on these things.

Brian Lehrer: We'll get to some of your policy recommendations to close the racial economic disparities that exist in this country today as we go. Listeners, we want to open up the phones for a few calls on this too. What do you think at policy level-- because this is a policy-oriented segment, part of our special coverage of the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

As we're hearing, the goals that have not been accomplished that were stated at that march in addition to-- Of course, there were goals that were accomplished that were stated at that march, but what policies do you think would most close the racial disparities in economics? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or any question you have from Kyle Moore, economist with the Economic Policy Institute, which has put out this report on economic disparities by race 60 years after the March on Washington. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or text your comment or question or policy suggestion to that same number, 212-433-WNYC.

I guess, Kyle, before we get to policy recommendations of yours for today that it would be interesting to just reflect on some of the many laws and policies that were enacted after the March on Washington. I guess if the disparities still exist to the degree that you were just pointing out, how much does policy even matter? I hate to be fatalistic or nihilistic about it. I think policy matters a lot.

Since then, they've passed the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, Medicare, Medicaid, Obamacare, these all post-date, the March on Washington, food stamps, and other 1960s public assistance programs, various degrees of affirmative action in the public and private sectors until, as you remind us this summer, Supreme Court ruling for the education sector, Pell Grants. What did all this accomplish in measurable improvements in equality? If very little, does policy even matter?

Kyle Moore: I think it is sometimes easy to fall into pessimism there, but I think the way that I look at this is that you have to imagine where we would be if we had done nothing, right? I think what we can recognize is that these policies needed to be put in place because the bear market on its own is not going to produce an equitable outcome for Black workers. In fact, if left to its own devices, there were forces within the United States for a lot of its history that would see Black folks in much worse economic conditions than they are.

We can look at what we've seen now and say, "Oh, we haven't made so much progress," but that progress has been constantly met with opposition the entire time. There have been pushes to move us forward, but it pushes back as well. Each of these policies that have been put in place have been really marked by compromise, right? We look at, say, for example, the Kerner Commission report that came out in 1968 that has a lot of really strong recommendations for things that should be put forward.

Not all of these were accepted by President Johnson at the time, right? This is, again, reflective of compromise with the political-economic powers of the time. There are things that we wanted to get done, things that people have been recommending for quite some time. Well, we can talk about policy recommendations later. We're looking at unemployment, for example. One of those things might be a federal job guarantee like guaranteeing folks the right to a job.

That's a policy that has been suggested for many years but was never fully taken up by the US government. You ask, what can policy do? I think policy can really do a lot. It's just a question of, do we have the political will to get these things passed without the compromises that would make these source of policies less effective that we've seen over the past decades that we've been trying to get these things done?

Brian Lehrer: All right, we'll take a short break. We'll come back. We'll replay one more clip from the A. Philip Randolph March on Washington speech that relates to the economics of today. It'll be eerie yet again like in that other clip that we played a little while ago, how much we're talking about the same things. We will hear specific policy recommendations from Kyle Moore from the Economic Policy Institute for what might close the racial economic gap in America today. We'll take suggestions from you, 212-433-WNYC, 433-9692, as we continue on The Brian Lehrer Show.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we commemorate the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the full title of the march. People forget about the jobs and freedom part and just think about, "Oh, March on Washington, 1963, I Have a Dream." We've been playing excerpts from one of the other key speeches of that day by march organizer and labor leader, A. Philip Randolph. Here's one more clip from A. Philip Randolph speech that will sound eerily similar to the same things we're talking about today. This is just 13 seconds. Listen.

- Philip Randolph: It falls to us to demand new forms of social planning, to create full employment, and to put automation at the service of human needs, not at the service of profits.

Brian Lehrer: Well, then they called it automation. Today, we're calling it artificial intelligence, but some of the same conversations that we're still having. We continue with Kyle Moore, economist with the Economic Policy Institute's Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy. They have just released a report in honor of the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington called Chasing the Dream of Equity: How Policy Has Shaped Racial Economic Disparities. Kyle, pretty chilling to hear that little A. Philip Randolph clip in terms of what we're still talking about today, right?

Kyle Moore: For sure. In some ways, it's disappointing to hear that we're still dealing with these same issues, but I think it's a testament to just how monumental of this task it is to change the direction of a country. It is always inspiring to hear from A. Philip Randolph. He was the labor unionist, the civil rights activist. He organized the first successful Black union in the country, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. I think hearing him speak in this context, in the context that they were actually at the march to hear just solidifies that jobs and freedom part of this.

These were people who were coming together to make political and economic demands. It wasn't just about voting, though voting is extremely important and democratic participation is important. A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, these folks were really committed to ensuring the economic well-being of Black folks and of the entire country. It's important to keep that in our minds. As fix of a place as we keep Martin Luther King and his speech there, even though Martin Luther King was also pushing for economic rights as well, but it's important to keep these thinkers in our minds as well as we think about where we've been and where we need to go next.

Brian Lehrer: You want to get into some more of the policies that EPI recommends in this report to close racial economic disparities? You mentioned one already, which is a federal jobs guarantee.

Kyle Moore: For sure. Unemployment is a scourge and it's something that we've dealt with for quite some time. Some folks just take it as a fact of the economy, "Oh, there's going to be unemployed folks." That's not necessarily the case. We can do things to get rid of that problem. We can put people to work. We've done it before. We've had the Works Progress Administration. We've put people to work in doing infrastructural projects and things like that throughout the economy, so that's an option.

The report as written, it's more so dealing with policies that are on the table right now in terms of like, where is the political will? What sorts of things are we working with? What's in the pipeline right now? Some of the policies we recommended there were increasing the minimum wage, right? That's something that's long overdue. It's something that I think is within grasp. The proposal is to raise the minimum wage.

The Raise the Wage Act of 2023 puts forward raising the minimum wage to at least $17 an hour. That's going to disproportionately benefit Black workers and their families because Black workers are more likely to work at and around the minimum wage currently. There's also going to be ripple effects throughout the economy, particularly folks at the lower end of the income spectrum where folks are going to be able to get raises. That's really going to benefit folks.

The other thing we can do, again, speaking about A. Philip Randolph, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, the PRO Act, which makes it easier for folks to unionize and to be able to increase union representation. Unions have been a real force in making sure that workers have that democratic representation within the workplace to advocate on their own behalf, to raise wages, to improve working conditions.

Putting working conditions in the hands of workers is a real step towards ensuring that they have economic well-being. Those are the two major policy recommendations we put forward in the report. Again, increasing the minimum wage through the Raise the Wage Act and increasing the likelihood and ability of folks to unionize through Protecting the Right to Organize Act. We can also increase access to fair housing through changing zoning laws that can happen at the municipal level as well.

There are also programs being put in place to solve the housing affordability crisis. Of course, we need to improve folks' access to democratic participation, generally speaking, through reinvigorating the Voting Rights Act. There's things that we can do in a lot of different places. There's no silver bullet here. There's not one policy we can pick, but it has yet to hit a lot of different areas.

Brian Lehrer: Did you consider including canceling student loan debt on that list? It's not there in the report, but I've seen that discussed frequently as a racial equity measure because student loan debt falls disproportionately on lower-income Black students from what I've read. Of course, there are barriers to higher education that run along racial lines. It's even more important in that context.

Kyle Moore: That's right. It may not be included specifically in the report. If we're talking about the racial wealth gap, if we're talking about again, like you said, the extent to which student loan debt burden has disproportionately fallen on which communities, I think you'd have to look at canceling student debt as a part of a racial equity plan, right? There's a report that we've been working on. It's not out yet, but we're looking at the relationship between student debt and homeownership, and just looking at the fact that having large student loan debt balances really affects the extent to which you can get mortgages. There are ways in which-

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that's a key connection.

Kyle Moore: -this debt burden is really affecting folks--

Brian Lehrer: Let me get one or two callers in here before we run out of time. Jodi in Maplewood, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jodi.

Jodi: Hi, Brian. Thanks for taking my call. I'm a really longtime listener. I'm a public school teacher. I wrote a dissertation about the connection between social class and public schools. One thing I'd really like to see is more subsidized housing in middle-income and higher-income neighborhoods so that families have access to the resources of those neighborhoods and of those schools.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. Madeline in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Madeline.

Madeline: Hello, Brian. Thank you for taking my call. Thanks for all you do. We're living in an era of unprecedented, out-of-control capitalism, the privatization of everything, education, health care, housing. There's an attempt now in front of the Supreme Court to undo rent regulation, yet again, by landlord groups here in the city. The only possible corrective, which I think your guest has articulated beautifully, is robust, ongoing public investment in these things, which we had. We saw a glimmer of it during the pandemic. We saw it certainly during the New Deal. FDR knew. The only way to save capitalism is by reining it in. [chuckles]

Brian Lehrer: Madeline, thank you very much. Your report references lessons from the pandemic. Of course, there was so much of that kind of social spending on an emergency basis. The expanded Child Tax Credit, for example, which I don't think comes up in your report, which everybody says cut child poverty in half. Certainly, that runs along disparate racial lines. The Republicans in Congress and a few Democrats who might or might not be named, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, didn't want to continue those.

Kyle Moore: Yes, I think one of the great policy lessons that we learned in this COVID recession is that-- oh, one positive thing we learned is that, "Oh, when we bring this bonding that matches the moment, we can actually solve crises and we can solve long-standing crises like child poverty," which, again, raises the question, "Oh, we have the capacity to do this. How can we only want to do this in the case of an 'emergency'?" Is this not always an emergency to see children hungry?

It really comes down to a question of what our political will is at the time. We've shown that we have the capacity to do this. Like our guests said, we've shown that in the past as, "Well, we've done these things," but it does take constant effort because, again, we live within capitalism. There are forces that will attempt to suppress these sorts of policies. It just takes effort. It takes constant effort. It's constantly a fight to put forward the policies that are going to make us whole socially.

Brian Lehrer: Kyle Moore, economist with the Economic Policy Institute’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy. They have just released a report called Chasing the Dream of Equity: How Policy Has Shaped Economic Racial Disparities. Kyle, thanks so much.

Kyle Moore: Thanks so much. Great to be on.

Brian Lehrer: That ends our special on this 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. That's The Brian Lehrer Show for today produced by Mary Croke, Lisa Allison, Amina Srna, Carl Boisrond, and Esperanza Rosenbaum, Juliana Fonda, and Miyan Levenson at the audio controls. Stay tuned for All Of It.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.