The Pandemic Will End Some Day

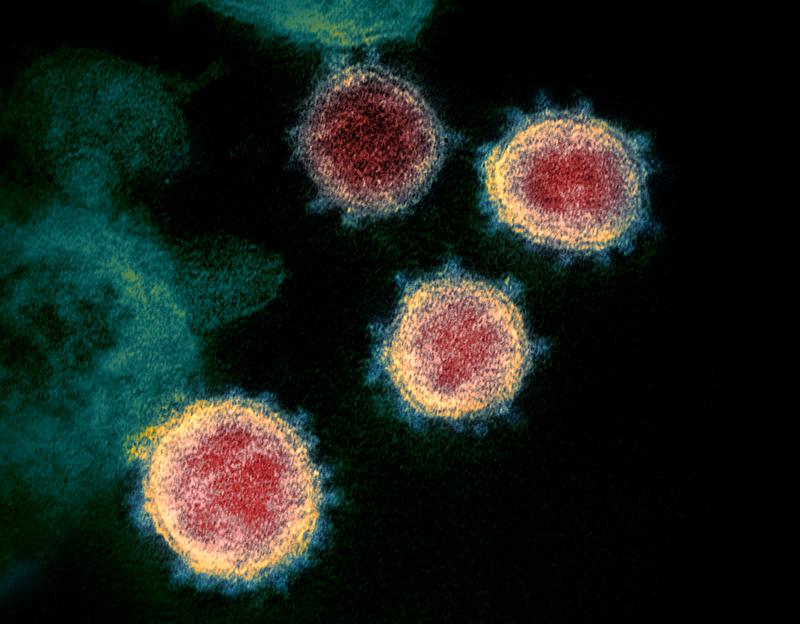

( NIAID-RML / Associated Press )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. About the pandemic, as August comes to a close, we are not at all where people thought we might be in this country by now. We all know that. It was only last month early July, doesn't it seem like a long time ago, when it looked like it was really fading, at least in places with lots of vaccinated people. The transmissibility of Delta and widespread vaccine refusal have gotten us back to where we were last winter.

The numbers are all the way back to where we were. 1,000 deaths every day from COVID nationwide, over 100,000 hospitalizations now. This doesn't mean that the pandemic won't end, however. My next guest, Ed Yong, thinks it will now end differently. Atlantic magazine science writer, Ed Yong, has done so much good reporting and good thinking about the virus since the beginning. His latest article is called How the Pandemic Now Ends. Ed, thanks for your work, and thanks for coming on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Ed Young: Hi. Thanks for having me again.

Brian Lehrer: Last year, when Trump was still trying to deny reality, you wrote that the US was locked in a pandemic spiral. Are we still in a pandemic spiral? If so, is it the same one?

Ed Young: I think we are, I was trying to suggest back then that we keep on making the same mistakes again and again that lead to bad outcomes. Out of the nine that I identified, the first one was what I called a serial monogamy of solutions, that we would only bounce from one possible control measure to the other and put all of our eggs in that basket. We're still doing that. We have done that arguably for much of this year in prioritizing vaccines over other things and even casting them in opposition to things like masks so that taking your mask off was almost seen as a reward for getting your shot.

That I think was folly even then, and I think it just cannot work in the Delta era. Delta is so transmissible that it cannot be controlled through vaccines alone. Now that's not to say that vaccines are unimportant. They are still one of the single most important things that we need to do, and the single most important measure that individuals can take to protect themselves. The truth of Delta is that vaccines cannot be the only thing that societies, that a nation does to protect itself. We need more than that.

Brian Lehrer: What did we drop? Masking regimens, testing regimens, what?

Ed Young: Masking is an obvious one. The CDC's initial slip flop on masking where it lifted indoor masking policies for fully vaccinated people was, to the views of many public health experts, a mistake. I think that has proven to be the case. They've reversed that rule, but a little too late. I think that period allowed for a lot of unhelpful legislations to come into effect that made it harder for local-level officials to put in masking regulations.

Testing you've also mentioned is a problem that has plagued the entire experience with the pandemic and still almost unbelievably continues to be a problem now. We never tested enough, we're still not testing enough. There was news reports really recently of hours-long lines to get tests in places like Florida. That's absolutely ridiculous a year and a half into a pandemic. It means that our understanding of what is happening around us is still imperfect. We still exist in this informational vacuum.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Although we could argue, tell me if you think this is wrong, that even without the vaccines, people should know how to avoid COVID by now through the behavioral protocols that we've learned along the way unless their jobs demand otherwise, which is too many people, "essential workers." For many people, masking, distancing, avoiding dense indoor spaces. If people were conscientious about those things, would we be having this Delta surge in the unvaccinated?

Ed Young: Sure. I think you're right that Delta isn't magic. Delta is just the virus virusing a bit harder. We know how to control it. Those measures, yes, still work against even this more extremely transmissible variant. I think people's willingness to actually do those things have eroded. I think a lot of the rhetoric we've heard has been unhelpful. The pandemic is still very much a collective problem that requires all of us to act as a community to protect each other's health.

I think the way vaccinations were framed really told vaccinated people that they could tap out of the problem, and it told everyone who wasn't unvaccinated that they were being selfish or inconsiderate when that is often not the case. I think that a lot of that individualistic rhetoric, it's your choice, your health is in your hands, was deeply unhelpful and antithetical to the collaborative community-spirited messaging that I think is needed in a pandemic.

Brian Lehrer: You also write that breakthrough infections in vaccinated people are rare but won't feel rare. Why that dichotomy?

Ed Young: They are still relatively uncommon. The Delta variant still poses the greatest possible risks to unvaccinated people. I think as the spread of the virus progresses and as it sweeps through communities, even rare events become numerically large. They become common to the perception. Even if you have say, just to pick a random number, 1% of breakthrough infections, that would still be a huge number of people who are experiencing this problem. Those cases will get a lot of attention, they'll get reported. I think they will cause anxiety out of proportion to how common they are.

It's a difficult thing to wrap your head around. The denominator matters. They are still relatively rare, but the numerator matters too. There's just going to be a lot of them. I think what's really important to remember is that we aren't actually back to where we were last year. Vaccinations do change things, and the most important thing that they change is that they protect people against severe disease, against things like hospitalizations and deaths so that a lot of these breakthrough infections will generally be milder than they would have been if people hadn't been vaccinated.

That's really important. We spent so much of last year terrified of this virus that was synonymous with COVID-19 the disease, but those two things aren't necessarily the same. The virus can cause the disease, but it doesn't have to, and vaccination can potentially disconnect the two. That is one of the most important changes between this year and the last.

Brian Lehrer: I'm glad you brought up the numerator and denominator [chuckles] issue because a lot of people don't get that. Let's linger on that for a second.

Ed Young: Sure.

Brian Lehrer: If 1,000 people who are vaccinated have breakthrough infections of COVID-19. Oh my God, 1,000 people. What if the number of vaccinated was 100 million? Does that tell us there's 1,000 and some of them are New York Yankees and other public figures? What does the media coverage tell us? Does it mislead us into thinking that the vaccines are ineffective when they're actually incredibly effective?

The numerator and the denominator in your article on The Atlantic reminds us of the breathtaking success of the vaccines. Here's some stats folks. No more than 3/10 of 1% of vaccinated people get breakthrough cases, and 95% of the people hospitalized for COVID are now unvaccinated. That's just worth saying out loud and remembering. Right, Ed?

Ed Young: Right, absolutely. You're right. Again, the denominator matters. If your hypothetical 1,000 people are only out of a much larger proportion, that is still the good news with vaccines. The point remains the numerator matters too. Those 1,000 people still got infected, some of them will get sick, and that number is just going to get larger the more the pandemic rages out of control. One thing I think is really important for people to remember, you hear a lot of stories about an outbreak in some community or some country which says something like a large proportion of those people who were infected or hospitalized were fully vaccinated.

The undercurrent there is always this is worrying. It's a sign that the vaccines aren't functioning as well as we hoped they would. That stat proportion of people who have been infected who were vaccinated is really misleading because it conflates two things. It conflates the actual severity of Delta and whatever it is doing, but with the actual success of the vaccination campaign. If you took a extreme hypothetical example, say you have a community where 100% of people were fully vaccinated. Then 100% of the people who are infected or hospitalized in that community will also be fully vaccinated. Do you see what I'm saying?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Ed Young: That messes around with people's perception of what is at stake because it confuses what the virus is doing with the vaccination campaign.

Brian Lehrer: Ed Yong is my guest. Science writer for The Atlantic. His latest article is called How the Pandemic Now Ends. We haven't even gotten to that premise yet, we've been just talking about the state of the pandemic at this moment. We'll get to how it now ends as Ed sees it. We can take a couple of phone calls, 646-435-7280, or tweet a question for Ed Yong @BryanLehrer. You write that experts used to think it was possible to defeat COVID so that it didn't really exist anymore and the pandemic would end that way, but Delta changed the game. Do you mean changed the game more than the previous surges about how the pandemic will eventually end?

Ed Yong: Yes. To be clear, I think a lot of experts were not massively optimistic that eradication was ever really on the cards. I think what Delta does is change it from a slim possibility into essentially a non-existent one. That's just because it is so transmissible. If you just do the maths based on how rapidly Delta spreads from one person into others, how effective the current vaccines seem to be, if you put those things together, the proportion of people you would need to vaccinate to control Delta to a point where it automatically fizzles out is either implausibly high or impossibly high.

What that means is that Delta can't be controlled through vaccination alone. It doesn't mean it can't be controlled, it means that we will need to pair vaccines with other measures such as masks, better ventilation, testing, and all the rest. It doesn't mean that the pandemic is inescapable, that we don't have any options. It means that that strategy of putting all of our eggs on vaccines and thinking that they alone are going to control the pandemic to a point where we can just go back to our regular lives is a fallacy. We can't do that. We need to do more than just to try and vaccinate people as well as trying to vaccinate people.

Brian Lehrer: Now you see COVID as not being wiped out in the way we may have once imagined, but it'll eventually become less of a threat because it will eventually become endemic. What does the word endemic mean in that context?

Ed Yong: It means that it's going to circulate around the world, it's going to be part of our lives, but at a stage where most people have some degree of immunity to it, either preferably because they were vaccinated or less preferably because they naturally encounter the virus, infected, and well survived. At that point, it's going to pose less of a danger. The danger that the virus poses is mostly because it's novel, because it's new, we don't have any immunological experience with it. When we get that experience, hopefully, because as many of us has been vaccinated as possible, then it's going to cause much milder disease.

It's going to not cause the same devastating surges that we're seeing right now that are capable of shutting down hospitals and shutting down schools. It will become still a thing that we will have to deal with, maybe a seasonal threat that spikes every winter but less of a society-changing threat than it is now. Of course, getting to that point is going to be hard. It's going to be challenging. It involves getting more people vaccinated, it involves slowing down the spread of the virus until that point.

We clearly cannot afford to just drop all of our defenses and rush into the endemicity end game, because as we've seen Delta spread so quickly that it is capable of overwhelming hospitals, crushing the healthcare system, of forcing school systems to shut down. We still have to buy ourselves as much time as possible even if we're heading towards an endgame where the virus is still part of our life.

Brian Lehrer: Speaking of places where the hospitals are getting overwhelmed, we have a caller from Florida who we are going to take. Elena in Dunedin, Florida, you're on WNYC with Ed Yong from The Atlantic. Hi, Elena.

Elena: Hi. Thank you so much for taking the call. I'm a physician. I'm interested in what he was talking about the numerators and denominators. So many people who are vaccinated are infected without knowing it, so many are asymptomatically spreading it. None of these people are likely to be tested and a lot is not being reported, and there's no contact tracing. I'm concerned that these numerators are underestimated hugely because of so many asymptomatic infections.

That's what I told the screener and I'd love the thoughts on that, but there's a second piece that this is such an unknown disease still. I know respiratory therapists working with people who had mild COVID a year ago and are still having long-haul symptoms just from mild disease. I'm concerned that we're thinking that we know so much about this disease that we don't long-term. There's no good data being kept on this and it can't be because it's too new.

Then the third thing is so sad about the masking. Of course, I'm in Florida, and it's just a nightmare that something that has so drastically cut the huge numbers of influenza deaths that we used to have, and is so commonplace in other countries just for courtesy when you have a cold has become so politicized that this hugely helpful tool is so not being used the way it should be. Those are my thoughts. I'd love to hear what you say.

Brian Lehrer: Elena, doctor, thank you for all those. Ed, what are you thinking as you listen to her?

Ed Yong: There's obviously a lot to respond to there. I think the ones I'll quickly say, yes, I do think it's ridiculous that masking a very simple measure has become so heavily politicized. I do think that Elena is right, that breakthrough cases are likely underestimated. It does seem clear that people who get breakthrough infections are capable of spreading the virus to other people, which is why, again, they can't tap out of a collective problem. That risk is lower than for unvaccinated people for a number of reasons. Just that vaccinated people clear the virus much more quickly. They have less time in which they could potentially spread it, and because they're less likely to get infected in the first place.

The issue that I want to talk more about is the very, very important one that Elena raised about long COVID. That still remains the pandemic's biggest and most important question mark in my mind. So much of the discourse around COVID hinges on extremes of either health or hospitalization in-depth, but there is this vast hinterland in between where people can often get mild symptoms and develop these rolling, relentless, debilitating symptoms that include extreme fatigue, brain fog, shortness of breath, post-exertion on the legs, so that's worsening of symptoms after any mild activity.

Long-haulers are extremely numerous. There's a lot of them. They're incredibly sick and there's not a ton of resources or answers for them. I've actually got a piece coming out very soon about long COVID and everything that we've just discussed. I agree that this is a huge thing we're not thinking enough about. When we enter this endemic endgame, what proportion of breakthrough infections might lead to long COVID?

We know that a few do, but I don't think anyone knows the rate. I don't think that we have good prior guesses for what the rate may be because the origins, the cause of long COVID are still unclear and are still being researched. While that is happening, hundreds of thousands, likely millions of people are incredibly sick. I've spoken to people last week who are well into their second year of symptoms. This is something that we absolutely need to be doing more on, that we need to be thinking more about, and that we need to be trying to actually measure and predict.

Brian Lehrer: Elena, thank you for all those points. Please keep calling us. Is there an issue of lack of genetic sequencing of COVID 2 cases in the United States that set us back like not testing early enough to see if cases that were emerging were the Delta variant or something else?

Ed Young: I think there is not enough sequencing and there could be more. We certainly have the technology and the ability to make that widespread. I'm not entirely convinced that is the primary reason why we were unprepared for Delta. I think there are lots of factors at play there, including we started this interview by talking about our repeated mistakes from last year. I think hubris is one of them. The start of the pandemic, the USA, rich medically powerful nation saw this virus ripping through East Asia and thought it was safe and it wasn't. The same thing happened with Delta, which we saw tearing a swath through India.

Somehow I think people felt that maybe it would be fine over here, even though half of the population was still un-vaccinated. That has cost us. You're right that a lack of information has been costly. Not just lack of sequencing, lack of testing, just a very poor understanding of respiratory viruses in general. Our last caller talked about long COVID. Long-haul symptoms can be caused by other infections too. Conditions like myalgic encephalomyelitis chronic fatigue syndrome, what proportion of those are caused by long flu or long other viruses? We don't know and we should know.

One of the things that I hope will emerge from this pandemic are a much better understanding of the long-term consequences of viral illnesses, full stop, and better systems for predicting and analyzing respiratory infections in general. Even when we get to an endimicty stage where COVID becomes less of the pressing threat that it is now, even if it becomes finally like the flu, the flu is still very bad news. Bad flu seasons are immensely costly in terms of lives and economic burdens every year.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, tens of thousands of people.

Ed Young: Absolutely. We could get much better at our ability to look at the spread of respiratory infections and at preventing them. Why aren't masks going to be a regular part of our lives? It would be a very sensible thing for people to stay at home when they're sick, to wear masks when they're starting feeling symptoms. We can change what we have considered normal because normal led to where we are now.

Brian Lehrer: A final thought before we ran out of time and I'm curious to get your reaction. I've been watching all these protests against vaccine mandates to get into places and mask mandates for schools and thinking that these are many of the same people who protested what the mandates are supposed to prevent, lockdowns. It was only a few months ago that indoor dining and gyms and theaters were all closed because small indoor spaces couldn't be made safe. Now they can more or less with these tools and yet we're in such a different place when last winter or spring in terms of what people can do even with Delta surging.

All these places are open and with no capacity limits and the masks and the vaccines are the tools we have to not have to go back to the lockdowns that people protested before. Remember Trump saying liberate Michigan before they tried to kidnap the governor? That was about actually closing things. Now everything's open because of vaccines and masks and they're protesting the tools.

Ed Young: Yes. Let's be clear. If you're protesting these things because they're you think that they impinge upon your freedoms, what about everyone's freedom to not get infected by the people around them? We all have a certain right to good health. Why are these protesters not protesting things like lack of paid sick leave? Just policies that would actually allow people to live healthier, safer lives and look out for each other as communities.

Brian Lehrer: We will leave it there for now with Ed young, science writer for The Atlantic who's done so many good articles covering the pandemic since the beginning. His latest is How the Pandemic Now Ends. Ed, thanks so much.

Ed Young: All right. Thanks, Brian. Take care.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.